Belonging

Season 7 Episode 20 | 26m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Belonging is a fundamental human desire that transcends boundaries - geographical, cultural, social.

Belonging is a fundamental human desire that transcends geographical, cultural, and social boundaries, encompassing the search for identity, acceptance, and connection within communities, families, and oneself. Grace shares how a green station wagon helped her family become Americans; Chris searches for the meaning of home; and in response to racism, Salil takes a different path.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Stories from the Stage is a collaboration of WORLD and GBH.

Belonging

Season 7 Episode 20 | 26m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Belonging is a fundamental human desire that transcends geographical, cultural, and social boundaries, encompassing the search for identity, acceptance, and connection within communities, families, and oneself. Grace shares how a green station wagon helped her family become Americans; Chris searches for the meaning of home; and in response to racism, Salil takes a different path.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Stories from the Stage

Stories from the Stage is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSALIL PATEL: I was about 15 years old, and there was a knock on the door.

Little did I realize as I headed to the door that my life was about to change again.

CHRIS KO: And I know what they're thinking.

How can someone who looks Taiwanese, and is living in Taiwan, not be able to speak the language?

GRACE TALUSAN: My father started to dream, and he started to wonder, what would it be like to stay here?

What would our lives look like?

What would the lives of his children be like?

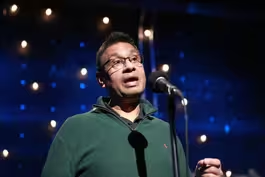

♪ ♪ KO: My name is Chris Ko.

I was born in Guatemala, and my parents were Taiwanese.

So, because of their work, I've had to move between Guatemala, the United States, and Taiwan.

And because of all the traveling I've done and the different people I've worked with, it's drawn me to immigration work, which has resulted in me working here in Boston now.

What do you feel like you learn from the people that you work with?

In my work, I interact with a lot of the, the refugees who come into the office and are newly arrived.

Mm-hmm.

KO: And I feel that, from interacting with all these people from different cultures, I've learned to not immediately judge people upon meeting them first time, but instead to better understand them before developing a, like, an impression.

When you think about storytelling, what's your favorite aspect of it?

To me, I think the most fascinating part of storytelling is that often, like, you either work or interact with someone for a long time, but you don't necessarily know, like, the deeper aspect of them.

Mm-hmm.

KO: And, like, when you hear a story about them that you didn't know before, it changes your perspective, and that's always interesting to experience, no matter who it's with.

How many times have you told a story onstage?

So, I've only ever told a story on a stage once before, and that was actually this past week.

And how are you feeling about your second time doing this?

It feels less nervous and more excited, and I'm really looking forward to it.

♪ ♪ This is the lowest I've ever been.

So low that the music from someone entering the 7-Eleven around the corner causes me to almost break down.

I turn to my friend who's sitting next to me, and I want to say something, anything, but I can't.

There's only silence.

I should probably start from the beginning.

I don't have a place that I can really call home because I was born in Guatemala to two Taiwanese immigrants.

I had the word "outsider" written all over me.

At school, I was the only Asian kid in a classroom full of Latino kids, who weren't welcome.

At home, I had no one to turn to, because my brother was too young and no one else was around.

One of my earliest memories is of me sitting in a classroom.

It's probably a Friday, because the teacher is asking us... (speaking Spanish) She's asking us what we're doing this weekend.

And all these kids, they're listing out places they're going, movies they're watching, things they're doing.

And I'm sitting here confused.

Why is the weekend so special?

Why does the teacher ask this question every week?

And I'm confused because my parents work seven days a week.

And on the odd holidays or days off, they would usually be busy catching up with chores or doing things in their own lives.

(inhales) To make matters worse, I didn't have any friends at school.

It was hard to make any when my parents couldn't afford babysitters or drive me around to different activities after school.

Instead, they would take me to the store that they owned every day after school finished.

It's a lot like the dollar stores that you see here, except everything was in quetzales, the Guatemalan currency.

And since it was a store with a lot of customers, they would always be busy with them, and I would have nothing to do but sit in a corner and think about the horrible things that happened at school.

One particular memory comes to mind.

(speaking Spanish) It's Augusto, shouting at me from across the yard, safely surrounded by his group of friends, something I'm reminded that I don't have.

This is third-grade recess, and gordito chinito sounds a lot like a cute playground rhyme that kids would say to each other.

But gordito chinito actually means "fat Chinese kid," and it stings.

It hurts because I know I'm fat, and it stresses me out to the point that sometimes, I will hide in the bathroom or pretend to vomit in the nurse's office just so I can skip gym class.

But I don't let Augusto know this.

Instead, I jump off the swing I'm on and I walk over to him.

Now, I'm obviously a big guy from what he said, and he's actually kind of a skinny kid, which makes this unfair.

But I punch him in the stomach as hard as I can and I watch as he falls over.

His friends are too shocked to react.

And if we're being honest, it feels good.

I feel powerful.

And it's one of the few moments in my life when I feel like I'm in control.

I walk away before they can do anything, and they never bothered me again.

I love Guatemala for a lot of reasons: the food, the weather, the culture.

But Guatemala also struggles with violence.

When I was in fifth grade, my uncle was killed in a botched robbery on the way to the parking lot from the store that we owned.

Crime is common there, but foreigners are especially vulnerable because they seem like easier targets.

And while I was born there and had been there for a long time, the way I look will always make me seem like a foreigner there.

Naturally, this event caused my parents to freak out, and they decided to send me to live in Texas with my aunt.

For a while, I was excited-- this was America, the place everybody wanted to go.

And I thought I would finally find a place to fit in.

It's about a month into the second semester of fifth grade, and the teacher's telling us to partner up for a math worksheet.

This girl who's sitting next to me, she turns around and she goes, "You know, you're a strange-looking Mexican.

But do you want to be partners on this one?"

(audience laughing, Ko chuckles) And she's smiling with these really cute dimples, and I can't help but say, "Yes, yes, let's be partners."

(audience laughs) I know she doesn't mean any harm by her statement, but it still stings a little bit.

As hard as I try, I can't seem to convince anyone here that, "No, not everything south of the border is Mexico."

(audience laughs softly) It's frustrating, but I don't make a big fuss about it because at least I have friends now, and that's so much better than being alone.

As I grew up, I developed this crippling fear of never belonging.

Fitting in is easy.

It's as easy as speaking the same way and pretending to like the same things as the people around you.

But belonging is deeper.

It's a sense of community, uh, an intrinsic sense of trust of the people around you.

And that was something I didn't believe I could ever have.

In ninth grade, my parents decided to send me to live in Taiwan so I could be closer to relatives and better understand the country that they were from.

I'm in beginner's Mandarin class now.

Mandarin is the predominant language in both Taiwan and China.

(speaking Mandarin) My teacher is telling me that my Mandarin sounds really bad, after I've just finished reading a passage.

At least she's honest about it, but she has the look on her face.

And it's the same look I get from the cashier at the grocery store, and the waitress at the restaurant.

It's the same look I get everywhere I go, and I know what they're thinking.

"How can someone who looks Taiwanese "and is living in Taiwan not be able to speak the language?"

I don't say anything to my teacher.

I don't usually respond to people.

Instead, I shift my accent slightly and I reread the passage to her in the way that she believes it should be read.

I pass, but deep down, I know that I've just given up another piece of myself.

Four years pass like this and I find myself back in the middle of that intersection where we started this story.

It's 5:00 in the morning and I'm about to have a meltdown.

I turn to my friend Pierre, who's sitting next to me, and I want to cry, to scream, to shout, to say something, anything.

But I can't.

Pierre's half-French, half-Taiwanese.

He's an outsider like me.

But he'd been there his entire life, and I thought he would never be able to understand what I was going through.

And so, that made it difficult to speak.

Suddenly, the 7-Eleven music rang again as someone walked out, and I started crying.

Now, I'm not generally very good at being emotional, but there I was, just sobbing in front of him.

And I turn to him and I go, "You know, as hard as I try, I can't be happy here, and I don't think I can ever be happy anywhere."

Surprised, he turned to me, and in a way only teenagers could, he goes, "Bro, what's wrong?"

(audience laughs) And I continue.

I tell him, "I'll be graduating soon, and I'll have to say goodbye "to all the friends that I've made here.

"And this will just be another place that I can't call home."

He thought about that for a quick moment, and then with a sudden anger that I'd never seen before, he asked me, "Are you kidding me?

"You've been everywhere, "but I've been stuck here my entire life.

"You don't have a home because you have many homes, and that's something most people will never have."

I wanted to say something back to him, but I was too shocked to respond.

Over the years, I've thought a lot about what he said that night and the way it's changed my perspective.

Here was someone who was my best friend, someone who I would have given anything to be, wishing he could be me.

And more than that, he was right.

While I can't stay in one place forever, I can always keep with me the best parts of each.

And at the end of the day, home isn't a place.

Home is an idea.

It's the people around you.

Thank you.

(audience cheers and applauds) ♪ ♪ PATEL: My name is Salil Patel.

I'm a PhD scientist.

I was born in Uganda, in Central East Africa, and I grew up in the U.K.

But now I've lived in the U.S. for about three decades, and I live currently in New Jersey with my wife and two children.

What have you learned?

You know, what has that journey taught you, like, going from Africa to the U.K. to the U.S.?

It taught me to appreciate people, but also to read people, and how to interact with, with very, very different people from all over the globe.

I understand that, you know, you're relatively new to storytelling and, you know, you've decided to come to this art and share your story with an audience.

Uh, what caused that desire?

How, how did you come to be interested in storytelling?

Well, I'm very proud of, of my sort of journey, and I think I've bored my children more than enough with the, the tales.

And I, I use the stories now to, to motivate people at work, to motivate my teams.

And I think storytelling is part of helping people understand who you are, but also getting to know other people.

♪ ♪ It was a sunny summer Sunday, one of those rare nice days in England.

I was about 15 years old, and there was a knock on the door.

Little did I realize as I headed to the door that my life was about to change again.

I was born in Uganda in Central East Africa.

Uganda used to be known by the British as the Pearl of Africa.

Uh, it's on the Equator, so beautiful weather, and our life was simple, but really nice.

Uh, we had lots of friends, we had lots of family in the surrounding town that we were in.

And I remember, it was always a very close-knit community.

And all of that beautiful life was changed when I was around seven.

A dictator called Idi Amin led a coup, and then came into power.

And following, you know, a lot of harassment, uh, months and months of it, he finally ordered the Indians to get out in 90 days.

The Indians loved Africa, but Idi Amin didn't love the Indians.

And so, we left essentially with the clothes on our back.

And with the help of the British government, we ended up in the U.K., first in a refugee camp, and then in the town of Swindon.

Now, Swindon at that point was predominantly white and a very working-class town-- completely foreign environment for us.

And my father started working in a warehouse.

This was a guy who was a teacher.

My mother was traumatized by having to wear pants instead of her usual sari to work in a factory.

And I was enrolled in Park South Junior School, which was just down the road from the house that I was in.

When I opened the door that day, stood there was a friend of mine, a neighbor, an English, white, white kid.

And he seemed to be reluctant to tell me what he wanted to tell me, and he was sort of looking at his feet.

Eventually, he told me to come outside and look at the wall.

And when I went out there, on the wall of our house, two feet high, gold spray paint, were the words "National Front: wogs, go home."

The hatred behind that message hurts, right?

But I wasn't so surprised, because that word, "wogs," which is a derogatory term for dark-skinned people, and the word "Paki" was thrown at me hundreds of times.

I even used to take different routes home to avoid the verbal abuse.

And many a times, I ran home because it was faster and, and nobody would pick on me.

And quite often, I was actually being chased by somebody.

And I remember being chased like a dog through people's yards, trying to escape a gang of skinheads.

And if it wasn't that, it was even worse.

I was at a soccer game once, and I had a knife put on my back.

Now, somehow, I was able to, to get through all of that.

Because... Well, I had no choice.

My, my parents were going through their own challenges.

And I really didn't want to burden them with, with my, my issues, and I was going to figure it out.

And those things, when somebody calls you a name, that's okay, you can deal with it.

But when you go to someone's house, your friend's house, and you hear the father turn around to the, the mother and say, "What's the Paki doing in the house?

", that's hurtful.

That's just not nice, and when you're, like, a 13-year-old kid, that hurts.

Another time, I had to go and pick up my mother from a religious event.

I was supposed to take care of her.

It was dark, it was 11:00, and the pubs had just emptied out.

And as we were walking home, a car pulled up beside us.

A bunch of guys pulled the window down and they yelled, "Curry-eating c-words."

Before I knew what was going on, they, they went a little bit further and a bunch of them got out of the car and started walking towards us.

My first instinct was to run, of course.

But I, I see my mother there, next to us.

And before I knew what to do, I'm looking at my mother, and she's praying.

(chuckles): And whatever she said to Bhagwan clearly worked, because those guys turned around, backed off.

They had their laugh, they scared us, and off they went.

So, when I looked at those words on the wall, yes, I was used to it, but those words, when they're on your wall, the hatred is on your doorstep.

And they also now know where I live.

So, the first thing I did was to try and cover up those words.

And we had some orange paint in the shed, and that's what we used.

And I painted it once, and I painted it twice.

And the shadow of those horrible words was still visible.

And my father said to me, "Don't bother painting it anymore, because if you do, they're just going to come back and do it again."

And so, I left those words, and for the next three months, every day when I came home from school, I had to look at that as a reminder that Salil Patel may have loved England, but England didn't love Salil Patel.

And when I went inside the house-- and by the way, as I was painting, there were lots of people looking on.

All of our neighbors had moved their net curtains and they were looking, but no one came out, no one said a word, no one had our back.

And we'd been very nice to these folks.

We, we had-- my mother had cooked for them.

You know, we were just good neighbors.

But they didn't, they didn't step up for us.

In fact, when I went in the house, some of them came out, and I heard one neighbor talking to the other and say, "You know, well, they, they deserved it," you know?

"They, they knew what they were coming here for."

Now, to be fair, the other neighbor said, "Well, that's not right-- that ain't right."

Well, the matter of fact is, we didn't have a choice, and we didn't know what we were coming here for.

And so now I was the angry teenager.

And I said to my father, "Why did you bring us here?

", and so on, and that day, my father gave the best talk of his life to me.

He explained to me that his own brother had been left behind in India, and he had been able to go to Africa because he had passed some senior exams.

And my father said to me, "Look, you can go wherever you want, "but you're not going to get anywhere unless you get educated."

And so, I studied hard, and I got myself into university.

And very few people went to university in those days.

And that was my escape from Swindon.

And from the day I, I got to university, I had figured out that a way to get to the U.S. was to do a PhD, and that's exactly what I did.

And now I live in New Jersey.

I've been in the U.S. for almost three decades.

So, is the U.S. free of racism, free of hatred?

No.

But the reason I like living here is, in America, there are lots of other people just like me that came from somewhere else.

♪ ♪ TALUSAN: I am an immigrant from the Philippines.

I came here when I was three years old.

I am a writer and I'm a teacher.

I teach writing at Tufts University in Boston, and I've been doing that for about 15 years.

Oh, great.

- And I really love it.

And why is this an important night for you to tell a story?

The story that I'm going to tell is about the fact that we were undocumented.

And even when I think about talking about that in front of an audience, I'm frankly, like, a little nervous.

And so, it's a story that has something to do with my father, and he'll be in the audience.

And so, that'll be... OKOKON: Mmm.

You know, it's a little odd or a little strange to be telling a story with him there.

♪ ♪ My father was the first to arrive in the United States.

His plan was to come here and further his medical education and then go back to the Philippines so that he could set himself up well.

So, he knew he would be gone for a few years.

So, he sent for my mother, my older sister, and I.

We always planned to go back to the Philippines.

So, my mother started, uh, collecting gifts to bring back home.

She collected bedsheets and towels and even toilet paper, because she thought it was just so much softer here than it was back home.

(audience laughs) But as happens sometimes, you go someplace and that place changes you.

So, my father started to dream, and he started to wonder, what would it be like to stay here?

What would our lives look like?

What would the lives of his children be like?

And so, he took a risk, and he took the exam for foreign medical graduates, and he passed.

And all of a sudden, this whole new world and future opened up for him and our family.

He opened his own medical practice, hired a staff, um, bought a house in the suburbs, and bought his first new car, which was a Chevy Caprice Classic station wagon, turtle green interior and exterior.

(audience laughs) And his idea is that cars are meant to be pragmatic.

They should get you from A to B, safely.

And so, one of the first things we did with that car is, we drove to visit his brother and sister in Toronto.

The family is really important in the Philippines, and we didn't have family in Boston, so that was one of the first things we did.

So, we all piled into the station wagon, we drove to the Canadian border, and the Border Patrol took one look at our station wagon, which was piled up with suitcases, and our passports, which were just about to expire, and he sent us back.

And he, um, I didn't know at that time, but soon after that, we, our status became, um, we became undocumented.

Our status became, um... We had overstayed our visas.

And my parents hired a lawyer to regulate our papers, but the lawyer didn't help and, um, took their money.

But it took maybe 15 more years until we were able to fix our status.

But I didn't care.

I didn't know any of this stuff-- I was a kid.

I was an American, as all my friends were.

I rode in that station wagon to school, to my activities, to band practice, to soccer, and I had no clue that this was all going on.

The only difference was that we didn't leave the country.

So, if there was ever a school vacation, we didn't find us in the Swiss Alps skiing, or in Cancún, swimming in the winter.

We took road trips in that green station wagon.

We drove to Florida, we drove to the Midwest, we went all over the South, and we saw how America was made.

We looked at the monuments and the battlefields.

We went to the White House.

We saw what, you know, what America wanted to remember, what they wanted to memorialize.

And we visited all those places in that car.

Now, my parents didn't want to spend money on fast food, so my mother would bring a rice cooker along on our trips and chicken adobo.

And we would have that at the rest stops.

And I would look really jealously at the other families, who were unwrapping peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and potato chips, and I just thought that was so exotic.

(audience laughs) They also didn't like to stop very often.

And one time, I saw them switch drivers without ever stopping the car on the highway.

(audience laughs) My father, uh, helped, kept his foot on the gas and he kind of inched his way over to the passenger side, and my mother held on really tightly to the steering wheel and, like, looked straight ahead, until she was able to inch the rest of her body over and then put her foot on the gas.

And we all cheered when they did that.

It was, it was great.

(audience laughs) So, we visited monuments and battlefields, but my father's favorite thing was to go on a factory tour.

First of all, it was usually free admission, and secondly, you would walk away with a parting gift.

So, we went to the Kellogg's factory, and it smelled so good.

The air smelled like corn syrup.

And there were these big, hot vats of cereal, and I just wanted to put my arm in and take some and eat it.

But it was boiling hot, so, good thing I didn't do it.

We went to the Chevy assembly plant, which was full of metal and really boring.

And we went to the U.S. Mint, which, we watched money get made, and we dreamed of what we could do with all that money.

The one place I remember is the cigarette factory in Richmond, Virginia.

And we watched all this messy brown tobacco get packed neatly into, into white cylinders, and then get packed into boxes.

And that day, every single one of my family members walked away with a free parting gift.

I got my first carton of cigarettes at age nine.

(audience laughs) So, we finally got our documentation regulated, and my father-- this was about 15 years in-- and my father was still driving that green station wagon.

And my mother felt kind of embarrassed, because he was a doctor by now and he would park in the doctors' parking lot at the hospital, amidst all the Audis and Mercedes and BMWs, and he had this ramshackle green station wagon in there.

So eventually, he decided it was time to let it go.

He thought it had tremendous value.

It brought a lot of value to my family.

And so, he parked it in the front lawn, put a cardboard sign up and put a price on there.

But every week, his heart would be broken.

No one wanted it.

And so every week, he crossed out that, that number, put a lower number on.

Week after week this happened, until eventually, he had to pay somebody $200... (audience laughs) ...to come and tow it away.

So, that green station wagon did more than just bring us all over the United States, and bring us to school and work.

It was the place where we became American, we learned what it was to become American, and we became that in that car.

And it brought us safely from new immigrant to citizen, from alien to belonging, from A to B.

Thank you.

(audience cheers and applauds) ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S7 Ep20 | 30s | Belonging is a fundamental human desire that transcends boundaries - geographical, cultural, social. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by:

Stories from the Stage is a collaboration of WORLD and GBH.