Black History is American History

Season 3 Episode 304 | 28m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

"Black History is American history."

"Black History is American history." Learn what our Black neighbors believe we should know.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

The Handle is a local public television program presented by Panhandle PBS

Black History is American History

Season 3 Episode 304 | 28m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

"Black History is American history." Learn what our Black neighbors believe we should know.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The Handle

The Handle is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Narrator] Warning.

This program contains strong language and racial slurs.

Audience discretion is advised.

(whimsical music) - [Narrator] A season at the protest in 2020, turned up the volume on the nation's dialogue about race and racism.

It's a talk we've begun and dropped for decades.

- [Male Narrator] If you're an American, if you love your country you have to talk about it.

- [Narrator] It's time.

The conversation starts with listening.

As conversations about racism have become more common.

So has advice for whites about being thoughtful with questions.

So we asked our black friends, what are you most tired of being asked to explain?

- I'm not a history major.

I don't constantly study history.

And so to be asked to explain a whole historical event when Google exists or when they had the same, like education that I had, it's kind of exhausting and ridiculous.

It's like, I don't know how to explain all these concepts to you.

I don't know everything.

And some people kind of expect you to.

Because it dealt with black history.

And that's impossible.

It's impossible and it's a ridiculous standard for black people to have to live up to.

You know, I'm not going around and asking everyone to explain every single detail of the Boston Tea Party or every single detail of the Titanic sinking, just because white people were there.

Like it doesn't make any sense.

- I don't know.

There lots of questions like about my hair and you know, they don't understand why does your hair do that?

I don't know it's in my DNA.

I think they're surprised to know that my family is very close and not dysfunctional.

And you know, they're surprised that we get together for birthdays and you know.

I just don't, people don't understand that we're just a family, just like anyone else.

- For me being a community activist what they're asking me is, why can't you let it go?

Why is it important to you?

And I just have to tell...

Excuse me.

Because I have children and grandchildren.

And if we don't get it right.

I don't want them to have to go through this like, we're having to go through this.

They deserve better.

They've worked hard.

And they deserve to have a life that right, the right to life liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

So when they ask, why do I do this?

I cannot not do this.

I cannot keep silent.

I wasn't raised like that.

- Have you ever been fired from a job because you're black?

Or you thought that you were fired from a job because you're black?

Or have you ever been beat up because you were, you know, African-American?

The answer to everything is, absolutely yes.

Have you ever been mistreated on your job?

Have you ever been denied a promotion because you're African-American?

Absolutely yes.

So the answer to your question is, I get tired of it, but I'll never stop asking the questions 'cause people have to know.

- Black history is American history.

But we keep getting left out of it.

- I would say that it's cherry pick, a few here a few there a few, a few this a few that.

My understanding of it when I was younger was black history was my ancestors got brought on a ship.

Boom, this is where you start at in America.

Is that's my existence?

That's it like... - It should be a seamless study with American history that should be taught throughout this nation.

But it's not.

Oh you may say a few words about Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King.

But the true history of the African-American principal as far as the contributions, is only on a scale on the periphery.

- That's been kinda emphasized in a month.

- Yeah.

- Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

- I think it really does more harm than good.

It makes people think that, oh, okay here's that black month.

All good.

Now that's over with, we can focus on the rest of what's important.

And it does a disservice to a Robert Smalls, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Ida B Wells.

You know, you have to be able to actually know how, you know, each of those people were part of more than just one movement.

You know, sure, it was the abolitionist movement, but they're also part of women's suffrage.

You know, there were other civil rights movements throughout our time in which African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, women, LGBTQ, were all involved and they all contributed to.

So, to really limit that to one month, I think it really, it limits people's exposure to what the truth and American history is.

- From kindergarten until my senior year of high school we were always taught that we were slaves.

I was always reminded of my oppression.

And never taught that I could be more.

And when we did, we got the same people, Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King and George Washington Carver and maybe Harriet Tubman and thank God for those people.

But to see, when I see somebody that looks like me in a position of power and authority or in a high position, it gives me hope.

Before Barack Obama, if somebody told me you could be president.

I would say, yeah right.

You never see a black person president of United States of America.

But after I see him in that position, I say maybe it can happen.

Maybe not for me, but maybe it can happen for generations to come.

Maybe it can happen.

So, when we see these systems of oppression and holding people back.

And not allowing people to have certain positions, it does create a mindset for people of hopelessness.

- I feel like to some, it conditions you to feel like you are only as good as the bad parts of your history.

To me, I grew up in a household where I was taught a lot of these things that most kids weren't.

So, I grew up knowing more about the positive and being able to embrace the positive parts of my culture not just hearing about the negative stereotypes and statistics.

But when you do grow up, only hearing about those, I feel like a lot of the times you end up becoming them.

We see that a lot in our black community.

Our sons are told from a very young age, you know you're not gonna be a good father.

You know, you're probably gonna end up on the streets.

You're gonna be selling drugs.

You're gonna end up in prison.

If that's all he grows up hearing, that's all he's going to grow up knowing.

And if we don't transition out of that, we're just going to continue the same cycle.

- Our side of it... (indistinct) And a lot of that reason why is, it will shine a negative light onto the majority of white America.

You won't be the good guy in this scenario.

You won't be the good guy.

And we all know, we all wanna be the good guy.

And so that's why we don't deal with these issues.

That's why we don't educate kids or teachers in school.

Because it doesn't make one particular race look good.

But that's the reality of it.

- I think it goes back to construction of the material.

Many times the authors that construct material are Caucasian.

So that is the perspective that the books are written from.

And other minorities may not be included in the construction of materials.

So that's where it starts.

The people that are constructing materials in their varied perspectives and backgrounds that they do bring to the text.

And so when it, that's beginning to change.

And there are more authors out there that are producing quality material that schools can use now.

So it's, explicit now.

It's, you know, people are being very strategic and looking for materials to address the needs of their students.

And not just to address African-American students.

To put it out there for the student body as a whole.

To provide a more realistic perspective of what America really is.

- So you have to be able to, you know, pull from myriad of resources.

Whether it's law regulated education or reading like a historian.

Or even your own personal stories and testimonies in order to get that student to understand how much of what happened in the past permeates even today and how that affects our future.

- But where does the culture really start?

You know, you go back to the roots of saying that we're from Africa, but then also once you get the roots of that, the self worth and who they were as individuals before they became slaves.

Then the transition of telling the story from slavery, how we got introduced to America.

And then with a value in who we were as slaves.

What our culture, you know what they picked up on, what they learn and then transitioning into history today.

And tell us just a long story, a long history line that hasn't been told, and hasn't been spoken of.

- I feel like there's been so much stripped from us that we might not ever really know.

I don't know what part of Africa my ancestors are from.

I can't trace my last name back to find out where it came from.

I trace, my last name back to a general that owned slaves.

That's as far and deep as my ancestry goes.

- I think you have to really begin with the middle passage.

What the transoceanic slave trade.

To understand how people were treated as property.

You have to really understand that, you know families were torn apart.

And the black mothers would have to be the caretakers of not only their children, but the children of the men and women that were oppressing them, holding them in servitude, enslavement.

I think you have to really get people to understand that you know, the anger, the sadness comes from the fact that, you know churches were burned to the ground, they were bombed.

That people were trying to exercise their right of suffrage were lynched.

That if you looked at someone and they perceived it as being aggressive or if you didn't look up and say, yes sir, yes, ma'am, you could be lynched.

Like you have to understand there were many wrongs that were done and a completely has an effect on us to this day.

- So we went to Alabama and the amount of history that we were able to see and be a part of.

It was very moving, but it really let me see what people had overcome to get to a certain place and knowing where you come from and what you've overcome helps you be able to know where you have the power to go.

Like the sky is the limit.

And I don't think because we don't have an in-depth understanding of black history, a lot of our kids don't see that.

I think the pinnacle of the trip was going to the Lynching Memorial.

It was very emotional.

It was a lot to be there.

They were all across the United States.

So the pillars that were hanging were divided by county.

So you could see how many people had died in that county.

And I was filled with anger, because I see where we are now and where we came from and I don't understand how that breakdown has happened.

How we got to this point where the value of the black life is so, so minimal.

It just made it real.

It made the struggles that we're going up against right now.

It made them real.

- I just think you can't fully grasp why the black community feels the way they do without knowing the history and how the white community has treated the black community throughout the years.

- For me, I think there needs to be a very, intentional acknowledgement on how slavery impacted America and how it made into a first world country.

And how that free labor made it possible for everyone to live in a very democratic and free world.

And that allowed us to gain the capital, to expand our land, to expand our power all around this nation and in this world.

- That I think other things that we need to know about are the witness of moment in time in Oklahoma called Black Wall Street.

Where you had very successful group of blacks.

And there were other communities, but this one is known as Black Wall Street.

In a 12 year time span after emancipation, blacks had their own banks, elaborate churches, airport.

I think we need to know about that 'cause that's something that's never taught about in school.

- When you see big blow ups like Ferguson.

When you see Baltimore,.

When you see Minneapolis in what then rippled across our country, it's frustration.

I've had this debate and argument with several people about rioting and looting and that sort of thing.

And Martin Luther King said a riot is the voice of the unheard.

This country was started by a riot, by looting, by destruction of somebody else's property.

And the irony of that is, the first man killed in that battle for independence in the Boston Massacre, laid that first bloodshed for the revolutionary war was a black man.

It's from where you stand the perspective of who's the hero and who's a revolutionary and who's the thug.

It's understanding both sides and seeing both sides.

You want me to learn your history?

You want me to learn about George Washington?

You want me to learn about Lincoln?

You want me to learn... Then you need to learn about Frederick Douglass.

- [Narrator] A cross burned on the lawn the day Amarillo College opened its doors to black students.

- [Willetta] I have never been so afraid as I was on that day, when that cross was laying on the ground burning.

As I went across, I started praying.

Our calls wasn't nothing but to get an education.

Willetta Jackson, February, 1999.

Within hours of the college's decision.

Jackson headed to class along with her sister-in-law, Freddie Imogene Jackson, Celia Ann Bennett and Dorothy Reese.

- [Willetta] That was years before we ever heard about Dr. King or Rosa Parks.

I just knew it wasn't right to pay tax and we couldn't go.

That's man's inhumanity to man.

Willetta Jackson, February 1999.

- [Narrator] Black residents in Amarillo had finally gained access to a college that had been receiving their property tax payments for years.

Amarillo College became one of the first three colleges in Texas to integrate, within limits - Amarillo college, wanted make it clear that integration was only for students from Amarillo.

For black students from Amarillo.

And that they did not want to have black students from elsewhere in the state.

- [Narrator] It would be nearly three years before a Supreme Court ruling would bar segregation.

- When I first come to Amarillo college, there was a few blacks.

They weren't very many.

If I had to guess probably 15-18 black students.

But, I had one very negative experience.

I was in a rush to get to the next class and I was reaching up into a locker to get my book, my English book.

And I looked to my right and I saw two white guys.

And I looked to my left, I saw two more white guys.

When I looked back to my right, I saw this fist coming.

This fist hit me in the face.

And I do remember one of the white guys said we don't want any niggers out here.

That was his word for me.

I got knocked to the floor of course.

And they beat up on me, kicked me in my ribs.

I had bruised ribs.

- [Narrator] It would be 1960 before black students were accepted into West Texas State College, which is now West Texas A&M University.

But to tell that story, means first looking at some earlier history.

In 1909 the city of Canyon made the winning bid to the state to become home to West Texas Normal School, a college for teachers that was the earliest version of WT.

Then a community of about 1400 people.

Canyon lured the college with 40 acres of land, $100,000 in cash, and a lack of saloons.

The bid also mentioned something else the city lacked.

- One thing that they, they told the state, why we should get it, is because we have no Negros, no Mexicans, no foreigners.

- [Narrator] The college opened its stores to "any white person of good moral standing,' in the fall of 1910.

Canyon allowed no black people to live in its limits for many years.

It was what's called a Sundown town.

- The Sundown town is ought to be, a town which usually will have a sign at the edge of the town which Canyon did.

Which says that blacks are not supposed to in the town after the sun goes down, during this time.

From what we have found, this really first appears in the 1930s.

And this was because of a all black unit of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

That was put into collegial fund.

Of course, that help, you know build the road, things like that obvious.

But there was a lot of fear.

You know, obvious people wrote letters from Canyon and from Amarillo, we don't like that.

- [Narrator] Canyon residents reinforced their preference for segregation, in August, 1953.

When the Canyon news published an article asking whether blacks should be allowed to move there.

Most of the anonymous letter writers spoke against the idea.

The next year a Canyon news editorial reacted to the Supreme Court decision, to strike down segregation in schools.

- [Man Narrator] As we have repeated time and time again, we know nothing about the Negro, since we have never lived in a community with him.

Fortunately, Randall County in Canyon have no blacks with which to contend.

Canyon News, May 26th 1954.

- [Narrator] In 1956 West Texas state college denied admission to Guy Raleigh Tomlin.

A civilian instructor at the Amarillo air force base.

But it was not due to his lack of qualifications.

Before working for the air force base Tomlin was principal of Frederick Douglass elementary school and Patent High School.

Two schools for black students in Amarillo.

He already had a bachelor's degree from Wiley college and a master's from the University of Southern California.

- What had happened is Texas had outlawed the NAACP in 1956 and '57.

So he didn't have that support group to go to.

- [Narrator] In 1959, Amarillo college graduate, John Matthew Shipp Jr, applied to continue his education at WT and was refused.

- But what the difference is that this time NAACP is not outlaw.

- [Narrator] Attorney W. J. Durham filed a lawsuit on Shipp's behalf.

With the help of NAACP, chief counsel, Thurgood Marshall, who would later become the first black justice on the Supreme Court.

- And they do take it to court.

And the state of Texas is gonna say, we're gonna help WT maintain segregation.

They admitted that the reason Matthew Shipp was not allowed into the university was because of race.

But they said, in Texas, we have the three tier system.

They said now the Brown decision, the 1954 Brown versus Board of Education, had said that, you have to have integrated schools in your state.

And Texas said, well we do have integrated schools.

Now, there are these segregated school and that's all that the brown decision said we had to do.

They didn't say we have to integrate all schools.

- [Narrator] Shipp won his case in federal court, in February, 1960.

But he attended college elsewhere.

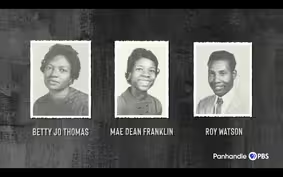

Betty Jo Thomas, Mae Dean Franklin and Roy Watson became the first black students at WT that fall.

A year later, the college had its first black graduate, Helen Neal.

By the way, the 1960 census counted more than 5,800 residents in Canyon.

None were black.

Claudia Stuart started classes at WT in 1967.

She became the first black student elected to the WT student senate.

And the first elected to the Homecoming Queens chord.

- I can remember being very idealistic, coming to school at WT was like a culture shock to me.

Because I came from Germany.

Military, you know we all live on the same bases together.

A lot of diversity, people from all over the world.

And coming to WT and it was like a fish out of water.

It was at a time when there was a lot of rebellion.

There were a lot of marches nationwide and we'd all marched together.

We'd all marched together.

- So the students they were accepting was the institution?

- Not really, not really.

We had to break down barriers.

We had a big controversy at the time that I was there with the Confederate flag.

The Confederate flag was a part of the Kappa Alpha fraternity.

- And they bring it to all the football games.

And they would wave it.

And they bring it to the basketball games then wave it and all this.

That actually the Kappa Alpha would dress up in some Confederate uniforms and they would parade through town.

- They had Old South Day.

They even had auctions.

They had people dress up in black face and have auctions in the student union building.

You know, all that had to change.

- [Narrator] In 1996, Stuart became WT's first full time, black female instructor.

- My deal, when I walked into the classroom, the first thing I said to my students who were all white, was I bet you've never had anybody that looked like me teaching you in a classroom.

And they said, never.

Never have I ever had anybody black teaching me in the classroom.

Okay, well now we go from there.

Okay, because we're here together, we're in it together.

And I wanna get to know you and I want you to get to know me.

- [Narrator] Next time on the handle, living while black.

- The only kids in Amarillo that are bused are kids that live in the North heights neighborhood.

- Carver was right up the street.

I could not even go to Carver in my neighborhood.

- For them to name it Robert E. Lee was a slap in the face.

- My mom, I remember telling me, you have to work twice as hard to get half the credit.

(whimsical music)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep304 | 11m 55s | Black Amariloans discuss the aspects of Black history that are often left out. (11m 55s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep304 | 10m 48s | A look at the history of segregation at Amarillo College and West Texas A&M University. (10m 48s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep304 | 3m 26s | Black Amariloans discuss things they're tired of explaining or being asked. (3m 26s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

The Handle is a local public television program presented by Panhandle PBS