Bring Them Home

10/2/2025 | 1h 18m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

Blackfoot tribe lead triumphant restoration of buffalo, culture & land in BRING THEM HOME.

BRING THEM HOME tells the story of the Blackfoot people striving to re-establish wild buffalo on tribal land after 100 years of absence. The film recounts efforts to restore buffalo, land, traditional culture and bring healing to the Blackfeet community. Narrated and executive produced by Oscar nominee, Blackfeet/Nez Perce actor, Lily Gladstone, the film has been an audience favorite at festivals.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Bring Them Home

10/2/2025 | 1h 18m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

BRING THEM HOME tells the story of the Blackfoot people striving to re-establish wild buffalo on tribal land after 100 years of absence. The film recounts efforts to restore buffalo, land, traditional culture and bring healing to the Blackfeet community. Narrated and executive produced by Oscar nominee, Blackfeet/Nez Perce actor, Lily Gladstone, the film has been an audience favorite at festivals.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Bring Them Home

Bring Them Home is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Aiskótáhkapiyaaya (Bring Them Home)

Bring Them Home reveals how the buffalo, once central to Blackfeet identity, spirituality, and survival, were nearly wiped out by settlers — an assault that devastated both the land and the people. For the Blackfeet, restoring the buffalo means reclaiming balance, kinship, and cultural healing.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(DRAMATIC DRUMBEAT PLAYS) (NARRATOR) We were born here, on the Great Plains.

Made from the clay of this land and given life by the breath of our creator, Napi Natoosi.

After making us, he made the buffalo, iinnii, out of that very same clay.

As soon as they took their first breath, they ran, and so did we.

(DRAMATIC PERCUSSIVE MUSIC PLAYS) (EPIC MUSIC BUILDS) (MUSIC FADES OUT) (NARRATOR) We have different names.

Niitsitapi.

Siksikaitsitapi.

The Blackfoot people.

This has been our home for millennia.

For almost that entire time, we've lived with and alongside the buffalo.

Known to some as the American bison, known to us as iinnii.

It's a bond that runs generations deep, but more than a century ago, that connection was almost broken... ...when we and the buffalo... ...became the targets of genocide.

(SOMBER MUSIC PLAYING) ("HOW I FEEL" BY THE HALLUCI NATION PLAYING) ♪ I could never imagine the pain that the mother saw ♪ ♪ When life takes a turn for the worst and creators all ♪ ♪ Becomes another canvas that will never be completed ♪ ♪ I'm a few degrees away and a thousand times defeated ♪ ♪ My energy's depleted but I wanna stand and fight ♪ ♪ So we can move the spirit ♪ ♪ Instead travel back into the light ♪ ♪ I feel the fears and depression ♪ ♪ Fears and aggression ♪ ♪ Woven into society from years of oppression ♪ ♪ The violence is normalized ♪ ♪ The silence is horrifying ♪ ♪ Truth is denied and the fact is more are dying ♪ ♪ You don't have to tell me how you feel ♪ ♪ 'Cause I can hear it in your cries ♪ (SONG CONTINUES) (SONG FADES OUT) (DISTANT BIRDSONG) (BIRD CAWS) (G.G.

KIPP) Every tribe on this continent... ...were provided with the means to sustain life.

Us on the plains was the buffalo.

Everything that we had came from them.

The lodges and our clothing and, uh, bedding and, uh, uh, food.

There was not one thing that we didn't use, you know?

You know, when we put up the okan, when we... When we built a temple for the creator out of the nature, the pivotal point of the ceremony was using the skull of the buffalo.

I mean, even, like, children's toys were made out of the bones of the buffalo.

And the horns were used as cups.

I mean, there's over 500 purposes for the buffalo body.

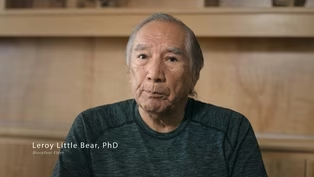

(LEROY LITTLE BEAR) But it was not just about subsistence.

There was a much deeper relationship with the buffalo than that.

In the native world, everything is made up of energy waves.

And, in fact, the energy waves are really what we would refer to as the spirit.

Everything is... animate.

There is no such thing as being inanimate.

So that's what we talk about when we say "all my relations," because I'm made up of energy waves, I've got spirit, see, but so does everything else.

So they're all my relatives.

So when we're talking about buffalo, we're talking about our relation, our relative.

(G. G. KIPP) We had everything.

The means to sustain a rich and healthy life was with us.

The bison was that gift to us.

But they wiped them out.

To wipe us out.

(DRAMATIC STRING MUSIC PLAYS) (DRAMATIC DRUMBEAT) (LEROY LITTLE BEAR) Part of the history was that the buffalo was annihilated, you know, almost to extinction.

And it was done so on purpose so that the Indians will disappear.

And along with that idea, there's always this notion of entitlement.

And so people came out over here, that is, Europeans came out, and they said, "We're entitled to this land.

We're entitled to the resources."

And so the buffalo, in no time, disappeared.

(NARRATOR) Over the course of the 19th century, in a coordinated, sustained assault promoted by the U.S.

and Canadian governments, buffalo were slaughtered from a population of more than 30 million... ...down to less than a thousand.

In the span of a generation, they disappeared from our lives.

(LEONARD BASTIEN) Well, I thought to myself, how I would feel if I kind of put myself in those moccasins at that time.

I would feel that, uh, gee, the world must be coming to an end.

The creator is coming to punish us and is taking away from us the greatest gift that he's given to us.

What did I do wrong?

What's happening?

What am I supposed to learn from this?

Where do I go from here?

What do I do now?

(NARRATOR) Without buffalo, our world collapsed.

The land suffered.

Animal and plant species that depended on buffalo for survival disappeared.

And we were divided and confined onto three reserves in Canada and one reservation in the United States.

In all of these places, our children were stolen from our families and put into residential and boarding schools where many of us faced horrendous abuse until we assimilated to Western ways of life.

On top of that, our language and culture was outlawed.

You could be sent to jail for speaking in Blackfoot or even for wearing an eagle feather.

This was a campaign of terror and assimilation that we still haven't fully healed from.

We see its consequences today in epidemics of poverty, depression, suicide, substance abuse, violence, and an ongoing crisis of identity... ...and loss of social purpose.

After all of this, most of us forgot about our relative, iinnii, but our connection was never entirely broken.

There were always some of us who believed that returning buffalo to our lands and our lives would help us to heal from our shared trauma.

It was a belief backed by experience and faith, one that grew into a collective effort spanning decades.

But all movements have an origin, and in this story, one of the first sparks was small, almost imperceptible.

(PAULETTE FOX) Growing up, there weren't any buffalo here on the reserve.

Um, nobody talked about them.

And, uh, the closest buffalo would have been in the Waterton Paddock, far from here.

I used to spend time on my own.

I was the youngest of six children and it was nothing for me to go off by myself.

And so one day when I was out on my own, I felt like I was being drawn, like I was being called, like this specific place wanted me to go and just sit there.

And when I sat in it, like, it embraced me, and it just sort of held me.

The warmth kind of overtook me.

And I can't say that I fell asleep, but I do feel like I slipped into... into something, And sort of out of the mist, I could hear breathing.

And I remember sitting up and looking around and being surrounded by buffalo.

And it was like we were communicating but there weren't any words.

I feel like their presence that day, what they were showing me, was very strongly that "We're here with you now.

We never left."

And it was almost like they were saying, "We're coming home.

And prepare.

Prepare for us to come home."

I-I was left with a feeling.

It's almost like a bit of a challenge, a bit of a mission, because I wanted to go get them and I wanted to bring them home.

(NARRATOR) Around the same time that Paulette on the Blood Reserve in Alberta was waking up to a desire to bring buffalo home, tribal leaders on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana decided they wanted to bring buffalo back too.

So they secured a herd from Yellowstone National Park... ...and turned them loose.

They were sort of like orphans, you know what I mean?

They kind of got passed around to different individuals within the tribe and they just were never properly cared for.

(TERRY TATSEY) During that early time of reconnecting iinnii back to the homelands, it wasn't widely accepted by our people to have the animal back.

For the ranchers, the farmers, when they see bison coming in and destroying crops or breaking fences and grazing on grass that they'd paid for, it didn't sit well with a lot of our own people.

(MOUSE HALL) (NARRATOR) This hostility wasn't shared by everyone on the reservation, but of those who adopted the cowboy way, it was common, an attitude that could be traced back to one government act.

Historically, we shared communal land, but after the creation of the reservation, in 1887 the U.S.

government passed the Dawes Act, which broke apart our land into relatively small plots given to the male heads of families.

It was an act designed to force us into ranching and farming, take more land for non-tribal homesteaders, and ultimately, to fracture our community.

Among many other challenges, the Dawes Act ultimately led to dependence on cattle ranching and a possessiveness of one's individual plot of land.

So when buffalo returned, the ranchers didn't see their relatives, they saw competition and threat.

After more than a decade of this conflict, the tribe enlisted a Blackfeet cowboy to corral the herd and teach them new habits.

(MOUSE HALL) (CHUCKLES) Ah.

(NARRATOR) Despite Mouse's best efforts, as time went on, the tension with individual Blackfeet ranchers and farmers only grew, until it reached a point where the tribe's leadership, the Tribal Council, decided to round up and sell most of the herd.

(MOUSE HALL) (PAULETTE FOX) I was in school in British Columbia and the family I lived with, they were watching the news, and I remember stopping because I heard them say "The Blood Tribe" and I was... "What's on the news?"

(NARRATOR) Around the same time that the Blackfeet Reservation's herd of buffalo was getting into trouble, north of the border on the Blood Reserve, there was another attempt at returning buffalo, one that gained national attention.

What happened was that the Blood Reserve's Tribal Chief decided to purchase a herd of buffalo without the approval of the tribe's governing body, the Tribal Council.

Despite the good intention, this didn't go over well with some members of the community, who decided to blockade the return of the buffalo.

You started this thing all by yourself.

You went and got the buffalo without Council's approval.

(WOMAN) Why do you want to stop the buffalo?

(PAULETTE FOX) And it was just based on a communication thing.

And in fact, our Sacred Buffalo Women's Society were trying to help them come home.

(WOMAN) Let's go.

-Why are you blocking?

-I am standing up for my people.

Why are you blocking our elders?

Standing up for the majority of the people.

(WOMAN) We are the people too!

(NARRATOR) The buffalo were sent back the next day, never to return.

(PAULETTE FOX) The best that I can gather is that... ...we were not ready.

You know, it was like if somebody talked about the past they would be laughed at, because boarding school taught them that those ways were gone and they had to go forward.

(NARRATOR) A year after the first Blackfeet buffalo herd was rounded up, the tribe decided on a new approach to bring back iinnii.

They kept a small number of calves from the first herd, bought some new ones, and raised them all in a confined area.

(BUFFALO GRUNTS) The idea was to create a new herd that would better respect fences before letting them out into bigger pastures.

This attempt included more hands-on management, like ear tagging and giving them feed, and opened up more of the management process to the community, including volunteers from Blackfeet Community College.

(TERRY TATSEY) When I went to work at Blackfeet Community College, I would take my students down there and we would help feed, we would help, you know, settle the buffalo into their new environment.

This is a very positive thing for our people.

It's exciting for a lot of our younger kids to come up and observe these animals.

(TERRY TATSEY) But what was happening while all of this was going on is a lot of our students... ...were so disconnected from our old ways and when they got to be around these animals, it gave them a sense of belonging, a sense of who they are as tribal people.

(SOMBER MUSIC PLAYS) (NARRATOR) Despite all the good these animals were bringing, there were still complaints from ranchers and landowners about buffalo trespassing and breaking fences.

Then, after eight years of this herd, around 2006, a new Blackfeet Tribal Council leadership came into power.

And because of these complaints, the Council abruptly decided to sell most of the herd.

(TERRY TATSEY) That was a little bit of a tougher pill to swallow for me.

But by the time the second herd was sold, we had enough support from the people in general to, uh, do this again.

I knew that there was more support than there was... ...when the first herd was sold.

(REPORTER) Bringing back the bison is an idea the Blood Tribe Lands Department is exploring.

(PAULETTE FOX) I think, from our perspective, it would be definitely driven by individuals.

(PAULETTE FOX) When I came home, I'd finished university and I came home, my role in the community at the time, I was an environment manager.

And when we moved to, you know, working with the buffalo, I could never find any funding.

Uh, there was nothing available.

And we were always working closely with the elders.

And so what our elders said to us was, "If you really want to get to the heart of who we are, you should really talk about the buffalo."

And I had been wanting to have this conversation for many years, so that's all I needed.

(SPEAKING IN BLACKFOOT) (SPEAKING IN BLACKFOOT) (LEROY LITTLE BEAR) We started to hold what we called "Buffalo Dialogues."

And sometimes we had gatherings of a hundred people, elders, young people and so on, other times smaller, but it was open.

(PAULETTE FOX) We said, "We just want to understand, through the language, the importance of buffalo, our relationship to buffalo."

And that brought about that ... ...if I can call it buffalo awareness, buffalo consciousness.

(PAULETTE FOX) You could tell it was bringing so much courage back to, um, just to have that conversation in the community about buffalo.

They said, "Our young people... ...hear these stories, they see our ceremonies, they hear our songs, but they don't see that buffalo out there."

Yes, we still had all of the beliefs and so on, but that external cognitive connection that symbolizes all of that... ...was missing.

Wouldn't it be great to see if we can have the buffalo... ...roaming around free over here like the old days?

We'd like to see free roaming buffalo.

(DISTANT BIRDSONG) (NARRATOR) In 2006, soon after the second herd of Blackfeet buffalo was mostly sold off, the tribe decided to make a third attempt, and started over with the newly formed Blackfeet Buffalo Program, which would be responsible for this new tribal herd.

Ervin Carlson, a cowboy who had managed the tribe's cattle business for a decade, was hired to lead it.

(ERVIN CARLSON) You know, buffalo was never... ...never a word when I was growing up.

Never heard anybody ever talk of buffalo.

You know, even in my grandfather's time, they didn't see buffalo, so... ...um, so yeah, it was just never there, never a part of the conversation.

And actually, I knew nothing about buffalo .

You know, never being here.

I'm doing the ranches for the tribe and the cattle, and that's all I knew, you know.

But, um... So, slowly I just started learning, um, what they were and what they were about.

I don't get out to the fields as much as I used to, and I used to be out there almost daily, you know.

And, uh... Of course, I'm getting a little older too, but in the beginning, I used to be to be almost just out there by myself, you know, doing the fencing and moving animals and... At times I would think, "Well, why am I doing this?

Why are you doing this?

It don't seem like anybody else wants them."

As the years went by with them though, I just... It just kind of became a passion with me to bring them animals back.

(NARRATOR) As Ervin's passion for buffalo was growing and the Blood Tribe elders in Canada were expressing a desire for free roaming buffalo, another group appeared with the very same wish: the Wildlife Conservation Society of New York City.

Their interest came from the unique ecological role that bison play as a keystone species.

(MAJESTIC MUSIC PLAYS) (KEITH AUNE) The ecological role of bison has been pretty well-articulated.

And one of the key things I try to stress with people is bear in mind this is an animal that, in some form, has been on landscapes in North America for hundreds of thousands of years.

So when we think about restoring bison, putting them on the land, we restore a whole ecological function, not just the function of that bison, but the whole ecological health of the land is restored by putting that keystone herbivore back into the system.

It's absolutely fitted to the landscape, meaning that it is tuned up to exploit that grassland, that forest land, in very specific ways and have impacts that are both good for it in the long term, but also good for other species in the community in the long term.

(NARRATOR) When bison wallow, they create areas that retain water for amphibians and certain flowers, and these mini-ecosystems create sustenance for butterflies and countless insects, who in turn feed birds and small mammals.

Bison graze in a patch-quilt way that creates space for all species of grassland birds, many of which also depend on bison fur for nesting.

They plow through deep snow, creating pathways for pronghorn and other animals to survive the winter.

Almost everything about how bison live and move through the landscape benefit other animals, insects, plants, and the land as a whole.

And it was for all of these reasons that the Wildlife Conservation Society reached out to the Blackfeet Nation.

(KEITH AUNE) So when I first went up there, the logical place to start was with someone like Ervin, but also Paulette Fox and Leroy Little Bear across the border.

And with that sort of small nucleus of folk, we began to see who else should we bring in to discuss this and help us evolve this idea of wild bison.

(MELLOW MUSIC PLAYS) (NARRATOR) This small group of both tribal and non-tribal members soon determined that the best place to release a wild herd would be on the Blackfeet Reservation.

Beyond the fact that buffalo were already there, it also bordered a million acres of public land known as Glacier National Park, which used to be a part of the reservation.

If released on its border, buffalo could roam freely into the park.

But the group knew that acting alone would be a mistake, a lesson learned from the earlier attempts on the Blackfeet Reservation and the Blood Reserve.

That was what not to do.

In other words, don't start from the top, don't start at chief and council level, right?

So we flipped everything around and we did the complete opposite.

(NARRATOR) Inspired by the Buffalo Dialogues, in 2009, they founded the Iinnii Initiative and launched an evolution of the Dialogues, including community events and presentations.

(PAULETTE FOX) The idea was that it was very much grassroots.

(ERVIN CARLSON) We met with elders a lot, and not only elders, but... ...younger college students, down to younger high school students.

(KEITH AUNE) It was specifically called out by the elders that this initiative needs to bring the youth into it and involve them in it so that there's a legacy, a future.

(PAULETTE FOX) And it was very clear that the elders, that they said that... "This is really good to put buffalo back," you know?

"We could call it restoration or conservation," they said.

But for us, in doing what we're doing, it's healing.

It's healing us, it's healing the land, and settler, colonial, and indigenous relations.

You know, how do we work together?

How do we help each other?

And so the healing is not just for the Blackfoot Confederacy, it's for... It's for everyone.

(NARRATOR) And in the course of these conversations, when the Iinnii Initiative spoke about the possibility of fully wild buffalo, they soon realized that they needed a new herd.

A very specific herd.

(NARRATOR) Back in 1850, a member of the Kalispel tribe, Latati, captured a small group of buffalo calves from the Blackfeet Reservation and took them to his home on the Flathead Reservation.

This free-ranging herd grew into hundreds, but the U.S.

government wanted that land for cattle and settlers and forced a sale of these animals to Canada, where they were transferred to Elk Island National Park in Alberta.

There, the buffalo thrived, safe for more than a century.

(KEITH AUNE) Almost everywhere else that there's been bison restoration, the buffalo came from different sources than where they originated than the original land.

In this instance, we could actually get bison that came from that landscape and bring them to the ancestral home.

And it's the only place that this could be done.

(PAULETTE FOX) For the Elk Island herd to return to the very place where they started out in their journey... ...is a powerful story for us.

It will mean a return to ourselves, to who we are as Blackfoot people.

(MAJESTIC MUSIC PLAYS) (KEITH AUNE) When we realized we could get some Elk Island bison and bring them back, we immediately went back into Dialogue sessions about how this should happen.

(ERVIN CARLSON) I wanted to bring adult animals back and start breeding right away and have a lot of animals, but in the state of Montana, we had, uh, always a little, um, uh, a fight with the Department of Livestock.

One of their rules is not letting adult animals into Montana.

So, consequently, all that was left was calves there.

I'm here today to bring home the buffalo that we've been talking about.

No more talk.

(CHUCKLES) (PAULETTE FOX) They invited Ervin and I to go down into the paddock with the buffalo and Ervin and I are chatting, and he said... (ERVIN CARLSON) These calves, they made it happen the way they wanted it to happen.

I always hate to really talk about it and sound kind of, like, cheesy or whatever, you know, but the spiritual side of it really hit me that day, that these animals left here as calves and they wanted to come back here as calves and grow up back in this, their home territory.

And it was that moment of the conversation that everything faded for me.

Like, I just turned and I looked at them and it brought me right back to my vision when they were showing me where they were going to be in the future, that they were going to come home.

And I was like, "Definitely, they want to come home."

(GENTLE MUSIC PLAYS) (SINGING IN BLACKFOOT) (SINGING CONTINUES) (ERVIN CARLSON) When we brought them home, there was a big celebration of people down at the Winter Camp... ...waiting for us to come home with the animals and, you know, they were there all day, waiting.

(PAULETTE FOX) No problems, no protests.

Everybody's excited.

And there's me saying, "You know, there was a time when this was impossible."

You know?

(CHUCKLES) And why is it possible now?

Because we did it in a gentle way.

We did it in a loving way.

It felt really good to see that everybody was there, and everybody was happy.

Um... And they're all supportive.

And, um... That they were so glad to have them back, it made me feel real good.

(MAN) Get back, guys!

Get back!

(DRAMATIC MUSIC BUILDS) (CHEERING) (ENGINE WHIRRING) (NARRATOR) With the Elk Island herd returned to the Blackfeet Reservation, there were now two herds that Ervin and the Blackfeet Buffalo Program needed to care for.

The Elk Island herd and the pre-existing tribal herd, which lived nearby on different ranges.

The goal was to set the Elk Island herd free so that they would be fully wild, but the challenge was to find the right location.

This was the land on the reservation dedicated for buffalo... ...and this was the land allocated for cattle grazing.

Nearly the entire reservation, including the mountain front, was full of cattle.

Nothing was immediately available.

So, for the time being, the tribe chose to keep the Elk Island herd isolated so that they could stay as wild as possible.

Because of this, the only way for the community to physically reconnect with the buffalo, to continue renewing that relationship, was with the tribal herd, managed by the Blackfeet Buffalo Program.

Caring for this herd, keeping them safe and healthy, was a lot of work.

Some of it up close and personal.

(DRAMATIC MUSIC PLAYS) Hup!

Hey!

Hey!

Hey!

Hey, hey, hey, hey, hey, hey.

Learning how to manage them in our world, today, sometimes we have to manage them that the way we know how with other animals, like the cattle.

So that means we have to get them in sometimes and, you know, take care of their health needs, whether that's vaccinations or sorting off the younger bulls so they're not cross-breeding or whatever.

But, you know, we need to work them.

(CLATTERING) (MAN) Let it go!

Oh, yeah, it's real exciting out here, but... Just got to get in the way so they go... Go the right direction.

Not too bad, I about kissed one right there.

Shoe got stuck.

(CHUCKLES) They coming running through.

Pretty scary.

You see that guy?

(ADRIAN CHUCKLES) Nowadays, you know, it ain't just like it was a long time ago.

You have to keep them herded, you have to work them.

But they're still a wild animal.

When you get them into crowds and stuff, you know, you'll find that out pretty damn easy, that they're still wild.

Oh!

(CLATTERING) -Whoa-ho!

-(MAN) Whoa!

(GATE SHUTS) (SOMBER MUSIC PLAYS) (NARRATOR) Days like this, while rare, were part of the conditions for keeping this herd on our cattle-dominated reservation.

This is the world we were forced into.

To fit into that world, this is what the Blackfeet Buffalo Program needed to do.

Without this work, there would be no Elk Island herd, no opportunity to rebuild a relationship with iinnii.

This was the cost of survival until the tribe's leadership decided that freedom was more important.

(INDISTINCT CONVERSATIONS) (WILLOW KIPP) When I started working for the Iinnii Initiative, I was really excited to do something that was going to be involved in the community and conservation and being involved with buffalo specifically.

I just didn't know or expect to be working in the tribal offices and going over to Tribal Council's side and trying to lobby for the buffalo.

The Tribal Council is made up of nine elected Tribal Council members.

Ultimately, any major decision, will go before council and be made by them.

So, when it comes to long-term projects like bringing buffalo back home initially everybody's on board with it and loves to talk about it and loves to hear about it and imagine it.

But when it comes down to the work of it, it's super frustrating.

You think that something is so simple and all you have to do is just put the buffalo out there and everyone is going to love it, but that's not the truth and that's not the reality.

Our Blackfeet community lives in a constant state of crisis.

We have alcohol, major drug addiction, poverty, and there's always so many little fires that need immediate attention that looking long-term, like how bringing buffalo back home can actually heal our traumas continues to get pushed aside.

And then when it comes to the buffalo, there's only so much land.

There's so much land for ranchers and farmers, and there's only so much land for wildlife.

The tribal budget depends on leasing, uh, range land out.

The significant portion of their budget comes from lease.

(WILLOW KIPP) When you have so much land being leased out for farming and ranching, it really makes it hard for land to be set aside for wildlife and specifically buffalo.

So anytime there's land that's set aside for buffalo, it means the tribe's not gonna have an income on that land year after year.

It creates a lot of conflict on what's important.

(JUNE WELLMAN) How many ranchers do we have, Blackfeet ranchers?

About... about 350, somewhere in that range.

And so the buffalo are in direct conflict for all the resources on this reservation.

The resource is the land that produces the grass.

Uh, buffalo are just a consumer of grass.

Cattle are the same way.

But, as ranchers, we have to depend upon that grass to make our living.

(JUNE WELLMAN) It's definitely conflicting in your heart, because on one side, you see the reintroduction of all our culture coming back.

You're so proud of the children that are coming up that are learning to speak their language, which, we were like discouraged, totally.

(DAN BARCUS) And our parents were abused for it.

(JUNE WELLMAN) And our parents were abused for it so we couldn't, but we were also colonized enough that Rob and Cindy were raised right from children with cattle, so that was also in their blood and in their souls.

So you're conflicted.

(SOMBER MUSIC PLAYS) (NARRATOR) This conflict, this legacy of colonization was the barrier to the Elk Island herd's freedom.

For them to be released, cattle leases somewhere would have to be retired, something that had almost never happened in the history of the reservation.

Facing this reality, the Iinnii Initiative embarked on a new mission, to create the space for the wild herd... ...to continue building the community's reconnection with the buffalo.

(HEAVY MUSIC PLAYS) (LEROY LITTLE BEAR) In the non-native world, everything was created by God for the benefit of man, see.

And if they're going to exist, it's because we're allowing them to exist, see.

So that savior approach is very much in the deep psyche of non-Indians as opposed to what's really deep in the psyche of Blackfoot Indians is about relationships.

See?

In Blackfoot thought, all of the universe is always in constant motion.

It's always in constant flux.

The best we can do is, in this constant flux, is really looking for reference points.

In other words, some things that might repeat themselves, see, like day and night... ...movement of animals... ...movement of stars and so on.

We say if we're going to exist into the future, then those repetitive patterns that give us life, that make us who we are, we have to renew those.

You and I, as humans, live in a very narrow gap of factors and conditions that are ideal for our existence.

If those ideal conditions and factors are not there or messed around with... ...we won't be around very long, you see.

So things like air... ...water, all the animals, all the plants, all the bugs, whether you like 'em or not, they play a role in this eco balance that brings about our continuing existence.

So that's one of the ideas behind the notion of renewal of the relationship, okay?

You have to renew those things that continue to give you existence.

(STIRRING MUSIC PLAYS) (OVERLAPPING CHATTER) (CHATTER CONTINUES) So this is what we're doing.

We'll have-- all the robes are in the center.

I'm gonna call everybody in, and he's gonna do a blessing.

And then we'll bring all the kids over inside the tipi, and we're gonna start the drive.

Everybody to the tipi!

All itsitsiimaan pookaks, babies, -you guys go to the tipi.

-Put the grass down.

(WILLOW KIPP) Iinnii Days.

This would be the second annual.

It's just a really community-oriented event to get the community involved and to let them know that we are buffalo-centered, like all of us, us as Niitsitapi.

And so it's just important to get our youth and babies thinking and seeing it again so they can say, "Oh, I remember I was part of the reenactment of a buffalo drive.

I know what happens in a buffalo drive."

(WHISTLING) (LATRICE TATSEY) This is needed because the access that people have is really limited, especially when they grow up in the larger communities throughout the Blackfeet Nation.

And so being able to share knowledge is really important.

The more we pass it down, the more that there will be access for generations to come.

Oh, you got little Wranglers on?

You're so cute.

Oh, I think about my son in everything I do.

Everything.

What I wanna do, where I wanna be, just revolves around what's gonna be the betterment for him.

I want him to grow up seeing buffalo as his relatives -and seeing them... -(SNEEZING) -Bless you.

Oh... geez!

-(CONTINUES SNEEZING) That was about 10 sneezes.

Um... Yeah, I want him to grow up seeing buffalo as his relatives and not so much like how we view cattle but knowing how to connect with them as relatives, not as animals that are separated from our lives.

(NARRATOR) As time went on, more and more people became involved in the Iinnii Initiative, and every opportunity was taken advantage of to provide face-to-face connection with buffalo.

Even the challenges provided opportunities, like the lack of land for the tribal herd, which only had two ranges on opposite sides of the reservation.

It was an ongoing struggle to make sure they had enough grass at any given time, but this distance and the necessity to move them back and forth ended up creating yet another opening for reconnection and healing.

(DRAMATIC MUSIC PLAYS) (SHELDON CARLSON) When we first start doing it on horses, we always, um, had a sweat, because it was-- we had a few people, you know, that didn't really know too much, but they had their horses hooked by buffalo, you know.

So I seen that.

So that's why we had the sweats.

We prayed just so nobody got hurt, you know.

But the drive was the, you know, it was the neatest thing to do.

(DRIVING MUSIC PLAYS) (SOFT, STIRRING MUSIC PLAYS) (WILLIAM CARLSON) When I first got with the herd, people always asked, you know, if you ever need a hand just call me, I'll come out and help you.

You know, they wanted to help just to say, "Wow, I went out there and I got to be around the buffalo for a day or for a couple of days."

They didn't wanna be paid.

They just wanted to be part of it.

That's all I'm saying.

They just wanted to be part of the drives.

I can say they never-- didn't ever do that before with the Buffalo Program, invited the old people, the treatment people.

Some of the schoolkids and stuff like that would come out.

Ow!

And we kinda like opened up a new jar of honey, you know, and just to let the people, the Blackfeet people know that that's theirs too, and they can help.

(STIRRING MUSIC PLAYS) When we first started doing the drive, the ranchers were pretty hard because, "Oh, my cows are in my field, the one you're going through."

Well, we have people in the front kinda moving it open like Moses opened up-- was that Moses that opened up that water, or somebody?

But we had to have somebody in the front.

We always had somebody in the front.

But after a few times and after we went through, they would actually sit out there in their trucks just to watch the buffalo go from their gate to their next gate, and they had their story, you know.

Some of 'em say, "Let us know next year, next fall or whatever, we wanna ride."

(STEVE TATSEY) I felt the same way like other ranchers do, they're just-- there's too many of 'em.

They're gonna take our grass.

But then after you work for 'em for a while, you feel different about it, but I don't know.

I can't explain that feeling that... Um, they just mean a lot more to you after you're with them every day and, you know, you start to care about 'em and what people think about 'em, you know.

You wanna change that.

(ERVIN CARLSON) Not even having any connection in the beginning, I mean, and being a part of ranching and... ...I didn't never had the idea that my ways could change.

You know, I still, you know, love that way of life, but, to me, what grew with the buffalo wasn't me looking at them as a commodity.

I realized that the things that we had to go through as Indian people, them buffalo went through the same thing, you know?

They were hunted and killed off to near extinction.

They were put in a certain place.

You can't be out on the landscape and be part of it anymore.

And there's things still today that are-that are against us, against them.

So daily, it's a continual fight for them, daily it's a continual fight for our people, so that's what makes me have that passion of, uh, the fight for my way of life, for my people and for them animals to be a part of that too.

(WILLIAM CARLSON) When I got with the buffalo, it changed my life too.

Like staying sober.

It helped me.

I can go out there days and I'm just thinking about, "Ah, just give up.

What the hell am I trying this for," you know?

But once I got around the buffalo... ...it's like those old ladies telling me, "Ah, no, no, my boy.

You're doing a good job."

Yeah.

(SNIFFLES) I'm done.

(NARRATOR) Over the years, as the ripples of reconnection spread throughout the community, the Iinnii Initiative always stayed focused on the ultimate symbol of acceptance: a wild herd.

And after weighing the options, they finally identified the prime location for the Elk Island herd to be released.

(SOFT, STIRRING MUSIC PLAYS) Ninastako.

That's Chief Mountain.

That's, uh, a very powerful place for the Blackfoot people.

We, uh, we go there and we fast.

Our people go there for visions.

Anyplace else in our territory, we can always see Chief Mountain wherever we are, and that's what our elders tell us: as long as we can see Chief Mountain, Ninastako, we're home.

This is our home.

(TYSON RUNNINGWOLF) It's really unique.

It borders up to Glacier National Park, Canada to the north, and, uh, Waterton to the northwest.

(WILLOW KIPP) Historically, a lot of the Chief Mountain area is owned by the Blackfeet Tribe, and they lease it out to ranchers in the summertime for their summer pasture cattle.

And that's... they're basically outside cattle.

(TYSON RUNNINGWOLF) So what happens is people will get a range unit, and they'll have maybe only 10, 20 cattle, but they'll get these thousand, 2,000-acre range units and they'll bring in white cattle, and then they just let 'em come in here.

They don't even check on 'em, nothing.

And as you can see, it's just overgrazed.

And then wildlife and anything that's in here suffers because they don't have nothing to eat.

Seeing them buffalo coming into the territory up here would be a... a great victory.

More than anything that we've settled in the last thousand years is bringing them back, 'cause they're gonna teach us our ways again.

That's where we learned all our ceremonies was from the buffalo, everything.

So our spirit's gonna finally catch up with our humanness.

(NARRATOR) In Indian country, we have something known as "Indian time"... ...which really means things will happen when they're meant to happen.

So even though Chief Mountain was chosen as the ideal release location... ...the realities of tribal bureaucracy and Indian time took hold.

Suddenly, it was seven years later... ...and the status quo for the tribal herd and the Elk Island herd hadn't changed at all.

(WILLOW KIPP) Seven years ago, the Elk Island herd made their way back home, but since they made it to the pasture that they're in, they've just been stuck there, and their herd isn't able to expand or flourish.

The biggest reason it's taken that long, the seven years, is... getting that land set aside, designated for them at, uh, Chief Mountain.

(WILLOW KIPP) It's an idea that everybody believes in, but when it comes to boots on the ground, when it comes to action, nobody's doing enough.

(TYSON RUNNINGWOLF) We don't have to be scared, but historical trauma has caused that other people in our tribe and other forces to think we have to ask permission from other people to do what we think is right.

Hell with them.

The release of the buffalo is a full practice of sovereignty as us as people.

We just gotta make it a priority.

(LEROY LITTLE BEAR) As so often happens, important issues become politicized, and people have different political camps and so on.

And, in this case, hey, the buffalo can easily become politicized, and, to a large extent, it is.

But, on the other hand, what has happened with the Iinnii Initiative is a very interesting question has become a reality.

What is it that really makes for a Blackfoot person, see?

Well, the buffalo is not hundred percent... ...part of the Blackfoot world.

But that buffalo, to a large extent, is keystone and makes for a large part of what you would call the Blackfoot world.

And so, when people start to realize, "Hey, this will make me much more... ...a complete Blackfoot"... ...things may eventually change.

(SOFT MUSIC PLAYS) (NARRATOR) Over the course of one lifetime, the challenges of bringing buffalo home might seem overwhelming.

But when you consider the tens of thousands of years we've been here in this place... ...it's nothing.

We know how to be patient.

We know how to survive, to endure.

We learned all of this from the buffalo, and following their lead, we chose resilience.

(SOFT INSTRUMENTALS PLAY) In the face of relentless obstacles... ...like buffalo in a blizzard, we turned into them and kept moving forward.

And with the Elk Island herd waiting, something started to build.

A momentum.

Teachings.

Planning sessions.

Meetings with Tribal leadership.

Celebrations.

Buffalo drives.

Over the last seven years with each step, the pressure grew and grew and grew... ...until the Tribal Council made a decision to temporarily set aside all cattle leases at Chief Mountain.

Finally, the path was open for iinnii to be free.

(TYSON RUNNINGWOLF) The critical time it's coming up here really fast, and if we wait any further, we're gonna miss this golden opportunity, 'cause politics will ruin that.

(EVERETT ARMSTRONG) So we'd like to see this as soon as possible.

We're tired of talking about it.

We wanna do it.

And I think that, uh the sooner the better, just like everybody else.

It's gonna benefit everybody, and if it fails, you know, there's a plan.

And we can plan for a better-- we'll know what to do next time.

I think it's something that we need to pursue.

We sit here and we talk and talk and talk.

I think it's time we put things in action.

(DAVE ROEMER) We're very excited that this project.

Uh, it checks all the boxes of what, uh, looks good for, uh... for everyone.

We're here to support the Blackfeet in any way that we can for this.

So I hope that the folks that are in here are good partners.

I hope the leadership has balls of steel-- excuse my French-- to just say "make it happen."

And I know that Ervin is all on board, and he's the man that can make it happen.

(ERVIN CARLSON) When the council set the land aside, I was all really very thankful for all of that for them.

And then the day that they come out and said well, we gotta have 'em there by this date, and it was real short notice, I had a lotta concern at first, lotta hesitation.

I thought, well, and for them, for protection of them animals, and them being safe there.

I guess you could say that I love them animals, I guess.

It's-it's... I don't know, something different to say, but I guess you feel that, you know?

You feel it here for them animals.

And that's a good feeling, to have it here for them.

(SOFT, MOODY MUSIC PLAYS) (STIRRING MUSIC PLAYS) (QUIET MUSIC FADES) (BACKGROUND CHATTER) -(MAN) Wow.

-(PERSON WHISTLES) (ERVIN CARLSON) I got this feeling, kind of a choked-up feeling just seeing 'em get out here and, uh, be here back to where they belong and, uh, I'm just so happy for them anyway.

So I'm glad, glad for this day.

It's a big day, yeah.

(FAINT CHATTER) (CHATTER, LAUGHTER) -All right, you guys ready?

-Let's go.

(LOW CHATTER) (MAN 1) All right.

There they go.

Check that lead cow maybe, that bull?

Oh, yeah.

(MAN 2) There they go.

They know what to do.

(FAINT CHATTER) (FENCE CLANGING) (PERSON ULULATING) Yi, yi, yi!

(CHORUS SINGING IN ALGONQUIN) (SINGING FADES) (BIRDSONG) (PENSIVE MUSIC PLAYS) (PERCUSSIVE MUSIC PLAYS) ♪ Call it perfect timin', better now than never though ♪ ♪ It feel incredible to have the iinnii back at home ♪ ♪ The future never set in stone ♪ ♪ But we let 'em roam ♪ ♪ This the pinnacle, put iinnii on a pedestal ♪ ♪ They tried erasin' ♪ ♪ But our people, they felt fake ♪ ♪ We never became complacent ♪ ♪ Natoosi told us be patient ♪ ♪ We got strong because of them ♪ ♪ They are strong because of us ♪ (RAPPING IN SALISH) (CHANTING IN SALISH) ♪ We brought 'em home, now Chief has the missing keys ♪ ♪ Hoofs on the ground, we returned what the village need ♪ ♪ They run the plains, we feel the breeze ♪ ♪ Overcome the pain, we heal when we see 'em freed ♪ ♪ We won the battle ♪ ♪ But still had to fight the war ♪ ♪ Restoration of our culture's ♪ ♪ What we're fighting for ♪ ♪ Everyone has to play a part ♪ ♪ And it starts with you ♪ ♪ For our wishes to come true ♪ ♪ We have to see it through ♪ (CHANTING IN SALISH) (CHANTING CONTINUES) (MAN SPEAKING IN SALISH) (END NOTES)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 11/24/2025 | 30s | Follow a group of Blackfoot working to right historic wrongs by returning wild bison to their lands. (30s)

All My Relations: The Blackfoot Way of Seeing the World

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 10/2/2025 | 1m 26s | Dr. Leroy Little Bear explains the sacred kinship and shared spirit between humans and buffalo. (1m 26s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 10/2/2025 | 3m 10s | Riders of the Blackfeet Nation unite in a powerful fall buffalo drive honoring heritage and spirit. (3m 10s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 10/2/2025 | 1m 37s | A Blackfeet cowboy’s efforts to protect the herd clash with rising tensions in the community. (1m 37s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: