Chasing the Plague

Season 22 Episode 10 | 55m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

Scientists study medieval bubonic plague victims in hopes of preventing future outbreaks.

Follow scientists as they track down the earliest known bubonic plague victims in hopes of preventing future outbreaks, while historians and scholars explore the societal impact of the plague on medieval Europe. What happens when a third of a continent’s population is wiped out?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

SECRETS OF THE DEAD is made possible, in part, by public television viewers.

Chasing the Plague

Season 22 Episode 10 | 55m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

Follow scientists as they track down the earliest known bubonic plague victims in hopes of preventing future outbreaks, while historians and scholars explore the societal impact of the plague on medieval Europe. What happens when a third of a continent’s population is wiped out?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Secrets of the Dead

Secrets of the Dead is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪♪ -In the middle of the 14th century, an invisible killer haunted Europe.

The Black Death was one of the most fatal pandemics in human history.

It tore society apart, and its impact is still being felt.

-It was one of those really crazy events that almost killed the entire Eurasian population.

-Can you imagine having no understanding of germ theory, no science, no idea what was causing half of the people you know to die?

-For centuries, people have studied this catastrophe, hoping to ensure it never strikes with such force again.

-Plague in common understanding is a disease of the past.

But the truth is that it's still an infection which is occurring today.

-It's very, very important to establish the origins of any disease.

-Now, a group of scientists believe an obscure collection of artifacts and graves discovered far from Europe may hold the key to identifying Black Death patient zero.

Is the origin of one of the most fatal pandemics in human history hidden in these stones, deep in Central Asia?

-10 headstones were specifically mentioning mawtana or pestilence as the cause of death.

-Could they mark the last resting place of the Black Death's first victims?

Ground zero for the worst disaster in European history.

♪♪ -The year is 1348.

All across Europe, millions of people are falling prey to a mysterious but deadly disease.

The symptoms are unmistakable -- fever and chills, body aches and fatigue, and painful swellings in the lymph nodes in the armpits and groin, known as buboes.

In the final stages of infection, the victim's fingers and toes turn black.

It is this last symptom that gives the disease its grisly name -- Black Death.

♪♪ As this sickness sweeps across the continent, piles of bodies line the streets, and once-thriving cities are transformed almost overnight into desolate ghost towns.

♪♪ One such city is Siena, in the heart of the Italian peninsula.

Situated on a medieval highway for merchants and pilgrims, in the 14th century, it was one of Europe's economic powerhouses.

Even today, Siena remains a Mecca for visitors, a World Heritage Site beloved as an untouched jewel of 13th- and 14th-century architecture.

But there is a dark story behind why Siena is a city frozen in time.

And that story can be found in an unparalleled record of life in the city over the year the Black Death hit -- a journal written by a man named Agnolo di Tura.

-He must have been taking a turn of writing, perhaps in the evening after his day's work.

He's a father of five.

He's got a wife.

Agnolo di Tura is a fairly ordinary Senese.

The thing which makes him so memorable is the Black Death hits on his watch.

-Today, Agnolo di Tura's journal is kept at the State Archives in the heart of Siena, overlooking its central square, the Piazza del Campo.

It is looked after by archivist and historian Cinzia Cardinali.

-[ Speaking Italian ] -Agnolo di Tura was a shoemaker, and the writing contains many aspects about his life, about which we still know very little.

-Agnolo writes that the Black Death arrived in Siena in May of 1348 and was gone by September.

In that short time, it decimated the population not only of the city, but of the surrounding area under Siena's control.

-We know that at the beginning of the 14th century, Siena was a city that had roughly 50,000 inhabitants.

So it was on a par with other European capitals at the time.

-While the population inside the city was around 50,000, the neighboring villages under Siena's control brought the total population to around 100,000 people.

-And he continues that in the city and the villages of Siena, 80,000 people died.

It seems a truly significant figure.

We can definitely say that it was a pivotal event that certainly changed the fate of Siena and Europe.

-An almost invisible intruder brought this deadly disease into Agnolo's home, as was the case for countless others.

Its effect was catastrophic.

For individual households and for entire cities like Siena, the Black Death changed things forever.

♪♪ The prosperity that Siena enjoyed in the 14th century, before the arrival of the Black Death, stemmed principally from banking and thriving trade networks.

Spices, silk, and other luxury goods were being imported from as far away as Asia via the ancient trade route known as the Silk Road.

And Siena was also one of Italy's main stopping points for pilgrims traveling to and from Rome.

-Siena develops as an important city because it's on one of the really important routes throughout the Middle Ages.

-Siena's cathedral sits on the pilgrim route known as the Via Francigena.

It ran for more than 1,200 miles from Canterbury in the south of England, through modern-day France and Switzerland, all the way to Rome.

-If you stick to the Via Francigena, you can be pretty sure of a bed for the night, because the towns along the way are sort of used to dealing with visitors.

-In addition to hospitality, Siena invented another way to cater to its many visitors -- banking.

The grand headquarters of Siena's medieval banking industry dominates the city even today.

-We're now on the part of the Francigena called Banchi di Sopra.

And a bancho was like a counter.

And so you'd have different sellers and money exchangers along the Via Francigena, selling their wares or exchanging money.

This would have been the banking hub of part of your trip to Rome.

-Siena's popularity with merchants and traders and its prime position on a pilgrimage trail are what made it prosperous.

But early in 1348, it was that same prosperity that made Siena deeply vulnerable.

In his journal, Agnolo di Tura described the horrifying scenes he witnessed during what he called the great mortality.

-The mortality in Siena began in May.

It was a cruel and horrible thing.

It seemed that almost everyone became stupefied seeing the pain.

It is impossible for the human tongue to recount the awful truth.

The victims died almost immediately.

They would swell beneath the armpits and in the groin and fall over while talking.

Father abandoned child, wife, husband, one brother, another, for this illness seemed to strike through breath and sight.

And so they died.

-Agnolo's first-hand descriptions of the Black Death paint a vivid picture of suffering and despair that was repeated all across Europe.

Key questions about the Black Death have remained unanswered for hundreds of years.

Where did this 14th-century pandemic originate?

And is it possible to find the earliest known victim?

One man has made it his life's work to find answers -- Professor Philip Slavin.

-I thought to myself, "Wow, it was one of those really crazy events that almost killed the entire Eurasian population."

And one of the questions that I've been really, really fascinated is where did it start?

Where did it come from?

-By the early 14th century, Europe was crisscrossed by a vast network of supply lines established over centuries of trade.

They carried people and goods by land and sea to every corner of the European continent and beyond, to Africa and the east.

-We know that in the 14th century, long-distance trade was really flourishing all over Eurasia, in different parts of Central Asia, western Eurasia, the Middle East, Northern Africa, Iran.

-But where people can move freely, disease easily follows.

-When we're talking about spread of any infectious disease, the most important factor is the movement of people and goods.

-And as a major trade hub, the Italian peninsula saw constant movement of people and goods.

And increasingly urbanized cities like Siena consumed a steady flow of goods and supplies from abroad, especially grain from the Crimean Peninsula on the Black Sea.

-The Black Sea region was a very, very important supplier of grain to Europe at that point.

-The ships transporting Crimean grain to Italian ports carried a stowaway as vicious as it was small.

Plague was already circulating in the area around the Black Sea in the 1340s, and on ships leaving Crimean ports, rats and fleas infested with plague set sail for Europe, and some human passengers were already infected.

-In September 1347, they arrived in Messina in Sicily.

That's the introduction of the Black Death into Europe.

That was the other port of entry into Europe.

-One by one, Italian port towns and cities fell to the Black Death.

By late 1347, the disease had been reported in Genoa and Venice and all the way to the Middle East.

By the following year, it had spread north through Europe to Germany, France, and all the way to England.

But this terrible disease ravaging Europe was not entirely new.

Agnolo's descriptions echo those of at least one previous pandemic.

The same symptoms -- the buboes that appeared in the groin, on the neck, and under the armpits -- were still seared into the collective memory.

Tales of a plague from some 700 years earlier.

-In the sixth century A.D., we see it for the first time emerging in a really abrupt kind of large-scale pandemic, the so-called first plague pandemic, the Justinianic plague.

-The Plague of Justinian is named after the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I, who reigned when the disease killed millions across the Mediterranean.

-Spread all over the former Roman Empire.

That's where we have historical sources telling us about it.

It could well be it was there before but we just don't have historical records.

-But what is plague?

It wasn't until another deadly outbreak, this time in China in 1894, that the pathogen responsible for causing Black Death was finally identified.

Physician Alexandre Yersin was the first person to isolate the bacterium, which earned him the dubious honor of having it named after him -- Yersinia pestis.

♪♪ There are three main types of plague, all caused by the same bacterium, all the same disease, but each causing different symptoms.

They are bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic.

The most commonly found form of the disease is bubonic plague, which represents about 80% of all cases.

-The bacteria transfer into the closest lymph nodes and start to replicate very rapidly.

-The individuals who are infected develop really swollen, painful lymph glands, so the glands in the neck and under the armpits and in the groin.

-These swellings are called buboes, hence the name bubonic plague.

If left untreated, the results can be deadly.

-This form of the disease can cause death in up to 60 or 70% of cases.

-While anyone contracting bubonic plague still has up to a 40% chance of survival, if left untreated, the Yersinia pestis bacteria can spread from the lymph nodes directly into the bloodstream.

This causes bubonic plague to develop into septicemic plague, a systemic infection that is much more deadly.

-This is when the bacteria enter the bloodstream directly, cause sepsis right away.

It's extremely lethal.

It can cause a death in almost 100% of cases.

-Once a patient's bloodstream has been infected with Yersinia pestis, the blood can also carry the bacteria directly into the lungs, causing pneumonic plague.

-Pneumonic plague is where the infection is in the respiratory tract, in the airway, and that people can then spread it to other people in their family, in their community.

-Coughs and sneezes expel tiny aerosol droplets carrying the bacteria into the air.

When someone inhales droplets from an infected person, they also breathe in the bacteria that causes plague.

The different types of plague can occur at the same time, both in individuals and the wider population, but it is when enough people develop pneumonic plague that the rate of infection soars.

-And that's really when the big outbreaks happen, when people are spreading it between themselves.

And the problem with that is that's more likely to be pneumonic plague, which has this incredibly high mortality.

That is then a rapid-fire spread of plague.

And we think that's what happened in the 1340s when plague arrived in Europe.

It spread rapidly between people.

-Once plague was present in the population, especially in a densely populated trading city like Siena, the extremely contagious pneumonic version of Black Death would have spread like wildfire.

It is believed that Black Death may have killed up to 200 million people, making it the deadliest pandemic in recorded human history.

-If we think about plague in the context of the recent pandemic, the COVID-19 pandemic, which most people are familiar with, that pandemic had a less than 1% mortality.

It spread all over the world.

It caused the most incredible economic disruption and the huge societal impact that it had from lockdowns and so on.

-At the point that the World Health Organization stopped collecting data on the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2024, there had been roughly 700 million recorded cases of the disease around the world.

Of these, more than 7 million people died.

1% of infections.

According to modern scholars' estimates, the mortality rate of the Black Death was roughly 50%.

-So we have to imagine plague as an order of magnitude different, with perhaps 30% or 50% of the population dead, not less than 1%, and the impact that that must have had on society.

-As the Black Death tore through Europe, people and physicians desperately scrambled to understand and combat the disease.

At the Wellcome Trust in London, Dr.

Elma Brenner has a manuscript that contains a variety of treatments for the plague.

Although this book was written during later outbreaks, the treatments it details would have been handed down from the 14th-century Black Death pandemic.

-The manuscript I have in front of me is an artifact that reveals how people lived with plague in the decades and centuries following the very first outbreak of the mid-14th century, and the manner in which it became part of people's everyday life, part of the culture of Europe.

-In many places, the plague would return every few years, making it a day-to-day concern best compared to the coronavirus or the flu.

Just as it is now, having ways to prevent and treat an infection was paramount.

-This treatment is a medicinal water based on rose water, vinegar, and other ingredients.

It is meant to be drunk by the patient, and it's a preventive treatment to prevent them from developing the plague.

Here I have another recipe against epidemic illness.

It's a list of ingredients and quantities -- many, many different plant ingredients that are meant to be dried and made into a powder that can then be added to water and either drunk by the patient or applied to their body as a medicinal water that enters the body through the pores of the skin.

-But sometimes the treatment was almost worse than the illness itself.

-Bloodletting was a treatment.

It was understood that bloodletting would expel the corruption of the plague from the body, meaning that there was a possibility that you might recover.

-Although the medieval understanding of germs, infection, and disease spread wasn't as advanced as it is today, providing relief to the sick was just as important.

In fact, one of Siena's oldest institutions provides evidence of the lengths people in the medieval world would go to provide care.

The Santa Maria della Scala Hospital was founded around a thousand years ago.

-Our first document of Santa Maria della Scala is really from 1090, when there was a xenodochium or a place to welcome pilgrims right next to the cathedral.

But the idea of having a hospital across from the cathedral is first mentioned in documentation at the end of the 12th century, and then throughout the 13th and 14th centuries, the hospital is enlarged.

-Although not originally a hospital in the modern sense, that changed because of the care visitors received over the centuries.

-You could imagine that many of the travelers did not arrive to Siena in the peak of health.

And so of course, the space was also used to treat the sick and the infirm.

All the way through the 20th century, this was the hospital of Siena and the emergency room right through the end of the 1980s.

-When Santa Maria della Scala finally closed its doors to the sick in the 1980s, it was the oldest operational hospital in the world.

But it wouldn't stay closed for long.

Deep underground beneath the hospital, a gruesome discovery was made in 1998.

It may reveal a direct link to the suffering experienced in Siena during the Black Death.

-We are in the bowels of Santa Maria della Scala, and we are standing right in front of the carnaio, or the charnel house, which was a mass grave in use from the 13th century all the way until 1572.

During the tragedy of the Black Death, these death pits would have been popping up all over, as burials needed to be happening as quickly and as efficiently as possible.

So far, there have been 2,260 skulls found in this death pit.

-It may seem like an unceremonious way to be buried, but the carnaio had an extremely important function.

-Because Siena was a pilgrimage hub, a lot of people who passed away on their journeys to or from Rome and the Holy Land may have died here in the hospital.

And if we didn't know to which family they belonged, if there was no one to claim them, to bury them in a cemetery or in a family chapel, they would be given a proper Christian burial here at the hospital.

So this is not just a place to dump bodies unceremoniously.

It was very important.

Part of the hospital's services to the city were to give people this proper Christian sendoff, because much of what the medieval person was concerned about is what would happen after this life, and so receiving proper rites would be of the utmost importance to those who were dying in the hospital beds up above.

-The carnaio served the spiritual needs of the deceased, but it also illustrates how the Senese attempted to mitigate the spread of infectious disease.

-The idea of spreading contagion even after the body had died was very much in the fore of the city council members.

And so these death pits, we know that they would cover each layer of bodies with quicklime to keep that miasma, that bad air, away from the rest of the citizens.

-The remains here have yet to be tested to determine what the people in this pit died of, but given the fact that the carnaio was definitely in use when the Black Death hit, it seems likely that the bones of plague victims would be among the thousands buried here.

-Certainly within this 2,260 skulls that have already been discovered, there might be some plague victims in there as well.

-At the peak of the Black Death, hundreds of people were dying every day in Siena, some of whom may have ended up being buried in the carnaio.

-The problem with the Black Death, when hundreds of people every day dying, there is no way to give a proper sendoff into the next life.

There weren't enough priests to go around to give last rites or to give that proper Christian sendoff.

And so there would have been more death pits open throughout the city.

-Agnolo di Tura's journal evokes the full horror of the situation.

-No one could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship.

Members of a household brought their dead to a ditch as best they could without priest, without divine offices.

In many places in Siena, great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead, and they died by the hundreds both day and night, and all were thrown in those ditches and covered with earth.

And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug.

-As people in Siena died in the thousands and the city's plague pits filled with bodies, so too did Agnolo di Tura's family members become victims of this terrible tragedy.

-So many died that all believed it was the end of the world.

I, Agnolo di Tura, buried my five children with my own hands.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -Siena and other places were decimated, but the cause of the infection that killed so many millions remained a mystery for centuries.

In 1898, more than 500 years after the Black Death, physician Paul-Louis Simond revealed that plague originated not in humans but in rodents.

-Plague itself is actually not so much a human disease.

The pathogen itself evolved to be a rodent pathogen to be transmitted from rodent to rodent.

It's transmitted by a vector, and the vector is actually a flea.

-And it is the way the bacterium affects the flea itself that enables the ease with which Yersinia pestis is transmitted.

-When a flea takes a blood meal, it takes up bacteria in the blood from an infected individual, and then the bacteria coagulate the blood and actually by that, block the stomach of the flea so that the flea cannot swallow more blood.

-The flea has become a super spreader.

-The flea changes its behavior because it's starving.

And because it's starving, it keeps on biting and it just doesn't bite like once, twice, or three times a day.

It bites hundreds of times, and every time it bites, it takes up blood, but it has to spit it out again.

And the blood comes in contact with the coagulated blood where the bacteria are in.

And then it spits out basically bacteria into the bite mark.

And by that, it transmits the disease.

-Plague can decimate the rodent population.

And if the fleas run out of rodents to bite, they look for a new meal.

That's when humans become the target.

One of the key mysteries surrounding the Black Death was whether it was indeed an outbreak of Yersinia pestis.

-I was approached very early on when I started my lab by a collaboration partner, and he had samples from a site in London, the East Smithfield, and which was from the Black Death.

-The East Smithfield plague pit near the Tower of London came into use in late 1348.

Thousands of victims of the Black Death, men, women, and children, were buried here.

-And he asked me if I can replicate a PCR that he had done where he had identified plague DNA in those samples.

-A PCR test is like a genetic magnifying glass.

It can find tiny traces of DNA and detect bacterial or viral infections.

-I said yes, I could, but I could go one step further.

We could actually sequence the entire genome of Yersinia pestis from those bones.

-As with other types of bacteria, Yersinia pestis will mutate to adapt to different environments.

These different mutations are known as the strains of a bacterium.

They all cause the same disease, but different strains might infect people more easily or better evade detection by a patient's immune system.

Identifying and understanding the different strains of a bacterium is essential in coordinating effective public health responses.

By sequencing the Yersinia pestis genome from the London bones, Johannes was able to identify the specific strain that killed these people.

What he found was surprising.

-We reconstruct the first genome of an ancient bacterium from bones from the past.

And that was Yersinia pestis from the Black Death, from the East Smithfield, from London.

And surprisingly, what we found was that genetically, it was actually the ancestor of the majority of plague strains that are found in the world today.

-The DNA of the strain found here in London matched DNA analyzed from other European sites, confirming it was a single strain of Yersinia pestis that resulted not only in the Black Death pandemic, but also in the centuries of plague that followed.

And in some places, it remains every bit as dangerous today as it was to Agnolo's family nearly seven centuries ago.

-Plague, I think in common understanding, is a disease of the past, but the truth is that it's still an infection which is occurring today in humans.

And there was a large outbreak in Madagascar just before 2019, about 2017.

And we also see sporadic cases in various parts of Africa, in Russia, in China, and in the United States every year.

-Today, if it's caught early enough, plague can be treated with antibiotics.

-In bubonic plague, that can be quite successful.

When you recognize the symptoms, you can use antibiotics for treatment.

-But what if antibiotics aren't easily available?

-The problem with pneumonic plague, the severe lung infection, is that if you don't treat it early, there is a 100% fatality.

And so you have to get in with your antibiotics within the first 24 hours of symptoms.

-Antibiotics need to be administered as quickly as possible for them to be effective.

But in a frightening 21st-century development, plague bacterium has begun to evolve in response to antibiotics, making the illness more difficult to treat.

-We are seeing some resistant strains, so strains of plague resistant to some antibiotics.

-The solution, then, to preventing a future plague pandemic is to develop a vaccine to stop people from contracting the disease in the first place.

And at the Oxford Vaccine Group in England, that's exactly what they're trying to do.

-So the Oxford Vaccine Group is a group of researchers who have been trying to work on the development of vaccines to improve human health over the last 30 years, and we've been involved in lots of different types of outbreaks.

And then, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic, where we were involved in the development of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine.

-Now the same group is developing a vaccine against Yersinia pestis.

Vaccine creation takes a long time.

Andrew and his team have worked on this project for more than a decade.

-This is Oxford Vaccine Group's lab, where the ChAdOx1 vaccine is made.

-Much of the underlying research done for other vaccines can be used in the development of the plague vaccine.

It uses the same carrier as the COVID-19 AstraZeneca shot.

-How it works initially is that we have the plague genes that encodes particular antigens that we want to make.

-An antigen is a substance that tells the immune system to fight an infection.

The principle is to develop a vaccine that encourages the patient's body to produce the specific antibodies that fight off plague infection.

Young Kim needed to test in vitro whether human or mammalian cells would produce the plague antibody after being given the vaccine.

Having demonstrated they do, the project can move on to the next stage.

Mice were injected with the vaccine to test how well their immune system responded.

Dr.

Sagida Bibi, who was also involved in the development of the COVID vaccine, demonstrates how this is determined.

-The color change is basically about determining how much antibody we've got in these plates, and it's an intensity of the color that matters.

We're seeing a visual color change.

This gives us an idea of whether or not this vaccine then needs to proceed to the next phase.

-The color change here to green indicates a positive result and suggests the team is one step closer to making a plague vaccine available.

-We had some confidence in then moving into human experiments, where we can see whether the vaccines are safe and they're protective, and we've conducted some early-stage experiments in humans here in Oxford.

-Early trials have been successful, but it can take years for a vaccine to be approved by any regulatory body in the world.

But as COVID has shown, when there is a global emergency, people can come together to get a vaccine into distribution remarkably quickly.

Developing an effective vaccine is just one way to prevent another pandemic outbreak of the Black Death.

-To understand exactly how pandemics are initiated is really important for us to actually be better defended against future pandemics.

-One key question that has remained unanswered since the 14th-century pandemic is where its particular strain of the Black Death came from.

Over 60% of infectious diseases have a hypothetical first human carrier who picks up the illness from an infected animal.

Once a disease makes that leap, it has the potential to spread to the wider human population.

This first person to be infected is called patient zero.

-Patient zero is the first human carrier of infectious disease.

The same person, he or she would receive bacteria or viruses from the other wildlife reservoir.

In other words, from animals, and in such capacity, the same person, he or she would be responsible for transmitting the same bacteria or viruses to wider human population.

In other words, we're talking about the missing link between the wildlife reservoir and the wider human communities.

Once we establish the so-called patient zero, we can also have very good approximation where this epidemic disease originated.

So this is something that can provide lots of very, very important answers for very, very pressing questions.

-The disease's origin has baffled some of history's keenest minds for hundreds of years.

And for a long time, it was accepted that identifying exactly here the 14th-century Black Death originated was impossible.

♪♪ In starting his search for the first known victims, Philip decided to trace the pandemic back through its entry point into Europe, the port of Messina.

This led him to the Crimea, where the ships carrying grain and plague set sail for Europe.

But beyond that lay the vastness of Asia.

Philip believed it was likely that the pandemic had moved west along the Silk Road from China, India, or even closer to home in the Black Sea region.

But Philip's breakthrough in pinpointing the cradle of the plague would come from an obscure collection of Central Asian artifacts.

In the late 19th century, Russian archaeologists excavated two sites near Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, Kara-Djigach and Burana.

From there, they recovered more than 500 headstones.

Each was inscribed with names and dates of the people who were laid to rest, and sometimes the cause of death was also recorded.

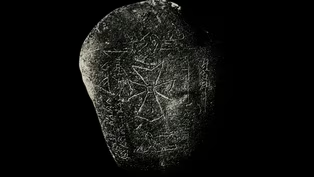

Most of the headstones are now kept in Russia, but one of them is located here at the British Museum in London.

-So here we have this wonderful headstone that was uncovered from the site called Kara-Djigach in northern Kyrgyzstan during the 1886 excavations.

And there's a wonderful Syriac inscription specifying who the person was buried there and when did he die.

-Derived from Aramaic, Syriac was not the Christian community's everyday language.

It was only used for ceremonial purposes.

It might be surprising to find Christians so far into Asia, but the enormous medieval trade network fostered immense cultural diversity.

-[ Speaking Syriac ] It says in the year of 1600 -- That is the year of 1288, 1289 according to the reckoning system that the local Christian community of Kara-Djigach were using.

That's about 50 years before the outbreak of the Black Death in the same community.

This is the grave of a person called Mashoud the priest.

Kasha means priest in Syriac.

-For Philip, these headstones represented an extraordinary snapshot of a community over an extended period of time.

-About 460 something, possibly 470 headstones have a precisely dated inscription so we can actually know when these people were buried.

The vast majority of these headstones also have the names of the individuals that were buried.

If you conjoin the information about the names and the dates, you end up with a very, very good chronological indication of the main demographic patterns within the same community.

-An increase in the number of headstones in one specific year caught Philip's attention.

-Then I just realized that there was one year when you had a remarkable spike in the number of annually chiseled headstones.

The year 1338, 1339, we have this remarkable spike.

-These headstones were dated almost a full decade before this wave of the Black Death ravaged Europe.

-I got even more excited when I realized that there were several of those headstones.

The 10 headstones were specifically mentioning mawtana or pestilence as the cause of the death of these people, say, "Well, wow, that must be it.

That must be really, really it."

So I really, really got excited.

-Philip had identified what he believed could be Black Death patient zero, the earliest known victim of the 14th-century Black Death pandemic.

But to be certain that this pestilence was actually the Black Death, he would require scientific proof in the form of plague victims' DNA.

The graves that these ancient headstones had marked were excavated more than a century ago, but amazingly, the skeletons were still in storage and available for scientific analysis.

-During the excavations, there were 88 graves opened at Kara-Djigach, and those graves contained 94 skeletons.

Now, some of those skeletons were luckily buried in those graves that are associated with the plague years.

And thankfully, some of those skulls were actually taken and were sent to St.

Petersburg.

That's how they ended up there.

At a later stage, they were transferred to the Kunstkamera Museum.

-And then Philip experienced an even more remarkable coincidence.

-Phil Slavin gave a talk at our institute.

He talked about A historical analysis that he did on gravestones from a cemetery from Kyrgyzstan close to Bishkek.

And when we talked about it, he had also said that he thinks that the skulls that were excavated were actually brought to St.

Petersburg, to the Kunstkamera Museum.

And fortunately, I knew the curators from the museum.

And then within a few weeks, we could actually assemble a team of people from our lab that actually went to St.

Petersburg to sample teeth.

-As soon as the human remains arrived from Russia, Dr.

Maria Spyrou and her team at the archaeogenetics department of the University of Tubingen started testing the teeth for microbial DNA.

They were looking for evidence that the so-called pestilence that killed the people buried in these graves was indeed the plague that swept through Europe.

As these graves pre-dated the previous earliest known victims of the Black Death by years, Philip knew that if Maria could positively identify they had died of plague, it would herald the discovery of a likely Black Death patient zero.

-This is how our collaboration started.

Of course, we have some evidence from the tombstones to indicate that this may have been a pestilence, but we had no evidence at the time that this was related to plague.

So the first question was to really try to answer, was this plague or not?

-Maria identifies what's known as ancient DNA or aDNA, from human remains hundreds of years old.

-Typically, this workflow would start with identifying the correct specimen to analyze.

In this case, because we were specifically looking for an epidemic context, potentially a blood-borne pathogen, we used teeth from these seven individuals.

-Teeth are commonly used in DNA analysis because the dental pulp at their center holds blood vessels and soft tissue, and they are protected by enamel, the hardest substance in the human body.

Maria has a team of people working with her to analyze ancient DNA.

-I'm Caitlin Mitchell, I'm a PhD student in the microbial archaeogenetics group here at the University of Tubingen, working with Dr.

Maria Spyrou.

-Like Maria, Caitlin extracts aDNA from bones and teeth.

-Typically, when working with plague, you are looking for ancient teeth.

So for instance, with plague, when it's severe, you have a very high bacterial load in your blood.

So if you've died from the plague, we would expect to see that there would still be pestis bacteria in the pulp chamber.

So that's why we drill there.

-Ancient DNA must be handled with extreme care, as it is easily contaminated by modern DNA.

-When you're working with modern DNA, you don't need all of this gear because you have so much DNA that any contamination would be lost with how strong the signal is from your modern DNA.

-Caitlin's work requires the painstaking recovery of aDNA fragments from centuries-old samples.

-After we sequence or after we kind of read out the A's, C's, G's, and T's from every fragment of DNA, we can then use the sequencing data to actually ask or answer the question of whether plague was present in those remains or not.

-Maria and her team then take the genome sequence derived from the ancient bacteria inside the teeth and upload it to an international database of known pathogens.

If Philip's theory is correct, the database will show a match that confirms Yersinia pestis is present in the samples.

-I didn't have very high hopes that we would be able to actually identify ancient Yersinia pestis DNA within those samples.

-But Maria's results would surprise the entire scientific community.

-The first result was actually that there was indication of Yersinia pestis being present in those samples.

So of course, this initial result gave us an incredible feeling for actually being able to eventually reconstruct an entire genome and compare this genome to others that had been reconstructed before from European epidemic sites.

-Once the work was complete, Maria was able to confirm her initial findings.

-Our study was able to specifically to indicate that the Black Death was not a pandemic that evolved or emerged locally within Europe, but was actually a pandemic that emerged outside of Europe.

-It would have taken the bacteria almost a decade to spread from where it first started in humans in Asia to Europe.

-The bacterium was introduced into Europe as a result of human movement 10 years or 8 years after this initial epidemic in Central Asia.

And so these genetic results provide evidence for the spread of the bacterium into Europe during the beginning of the Black Death.

-When Maria e-mailed her results to Philip, what he saw astonished him.

They confirmed everything he had been hoping to find.

-It was so unbelievable that I actually -- I couldn't believe it was true.

I had to pinch my cheek, just, you know, to make sure that I wasn't dreaming.

-Philip had finally found what he had been looking for for many years.

-Re-read the e-mail and yeah.

What was really amazing is that in the same e-mail, Maria also informed me that it wasn't just plague, but it was the origin of the Black Death.

-For Philip, this was a moment of triumph, the culmination of decades of work.

Clear confirmation that the headstones from the graveyard at Kara-Djigach and Burana did indeed mark the resting place of the earliest known victims of the Black Death pandemic.

♪♪ For hundreds of years, the mystery of where the 14th-century outbreak began has confounded historians and scientists alike.

But now the combined work of Philip Slavin, Johannes Krause, and Maria Spyrou has shown that the victims lived in what is now Kyrgyzstan and died in the year 1337.

It is here or close to here that one can assume the disease first jumped species from animal to human.

-We can hypothesize that it was certainly one of those nomads, one of those local herders that were wandering around the grasslands, and it was just very unfortunate to have come into the very first contact with one of those infected rodents.

-One bite from a flea that jumped from an infected rodent would have been all it took to start the deadliest pandemic in human history.

From this small community in Central Asia, the Black Death then traveled along the trade routes that spread from the Far East.

Within a decade, it had reached Europe, most likely through the Italian port of Messina, and from there it moved across the continent like a wildfire.

-The Black Death undoubtedly had a huge impact on society.

We know the economic impacts of it.

It changed social structures.

-In cities like Siena, it caused rapid devastation, killing tens of thousands in the space of a few short months... ...leaving an indelible mark on the people... ...and on the city itself.

-The plague absolutely decimates the population.

Within a period of four to five months, the population of Siena went from approximately 50,000, down to about 25,000 people.

-The Black Death didn't just claim human lives.

Siena was itself a victim.

Its unfinished cathedral, which dominates the city to this day, is evidence of that.

Work had begun on Siena's new cathedral less than a decade before the Black Death hit.

-The Senese wanted to make the largest church in all of Christendom.

And where we're standing right now is what should have been the facade of this new cathedral that would have been one of the largest in all of Christendom.

-The plague took the lives of the people building this new cathedral, from the workers to the architects, and construction ground to a halt permanently.

In his journal, Agnolo di Tura sadly wrote... -The city of Siena seemed almost uninhabited, for almost no one was found in the city.

This time in Siena, the great and noble project of enlarging the cathedral of Siena that had been begun a few years earlier was abandoned.

-Countless families experienced similar heartbreaks to those described by Agnolo di Tura in his journal.

♪♪ The Black Death pandemic would ravage Europe until 1353.

But even after the immediate threat ended, the disease returned repeatedly in the centuries that followed.

♪♪ And to this day, it remains a threat in certain parts of the world.

-It is considered a re-emerging disease in many parts of the world, and what our research was able to show is that likely a natural reservoir gave rise to one of the biggest pandemics of our history.

And so close monitoring of plague reservoirs across the world should be among the priorities.

-Thanks to the work being done by the team at the Oxford Vaccine Group, science may finally conquer the plague and consign it to the history books.

-If there was a major outbreak of plague that happened today, the spread between places would be quicker, but also hopefully our ability to communicate, to lock down, and to put interventions in place to save people's lives would be very different today as well.

-And the newfound knowledge of where the Black Death originated can help combat future pandemics more effectively than ever before.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S22 Ep10 | 1m 57s | The haunting journal of Agnolo di Tura reveals the horrors of the Black Plague. (1m 57s)

Could This Be the Black Death’s Earliest Victim?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S22 Ep10 | 3m 21s | Ancient gravestones in Kyrgyzstan hint the Black Death began long before it reached Europe. (3m 21s)

How the Black Death Set Sail for Europe

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S22 Ep10 | 1m 5s | In 1347, ships reached Sicily with the Black Death. In a year, it spread across Europe to England. (1m 5s)

The Pandemic That Killed Half of Europe

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S22 Ep10 | 1m 28s | The Black Death may have killed nearly 50 percent of the Europe's population. (1m 28s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S22 Ep10 | 32s | Scientists study medieval bubonic plague victims in hopes of preventing future outbreaks. (32s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

SECRETS OF THE DEAD is made possible, in part, by public television viewers.