Deadly Sins

Season 1 Episode 14 | 26m 54sVideo has Closed Captions

Sometimes our switch gets flipped and we lose control. Hosted by Theresa Okokon.

Most often, we do the right thing. But sometimes, our switch gets flipped and we lose control. Kevin goes postal in the post office; Ashley's patience is tested by FEMA after a flood in her community; and Khuyen has his life stolen by a life-tracking app. Three storytellers, three interpretations of DEADLY SINS, hosted by Theresa Okokon.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Stories from the Stage is a collaboration of WORLD Channel, WGBH Events, and Massmouth.

Deadly Sins

Season 1 Episode 14 | 26m 54sVideo has Closed Captions

Most often, we do the right thing. But sometimes, our switch gets flipped and we lose control. Kevin goes postal in the post office; Ashley's patience is tested by FEMA after a flood in her community; and Khuyen has his life stolen by a life-tracking app. Three storytellers, three interpretations of DEADLY SINS, hosted by Theresa Okokon.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Stories from the Stage

Stories from the Stage is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ KEVIN GALLAGHER: So I gather up all my credit cards and my cash and my envelope, and I scurry out the door before security came for me.

ASHLEY ROSE: Eventually, I hear the sound of water.

Within the next hour there's a firefighter at our door saying that we have to leave on a raft.

KHUYEN BUI: I started to cry.

What the hell was I doing in my life?

Why did I make it so hard?

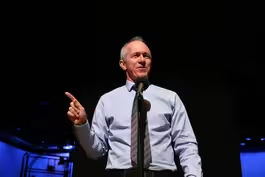

THERESA OKOKON: Tonight's theme is "Deadly Sins."

ANNOUNCER: This program is made possible in part by contributions from viewers like you.

Thank you.

OKOKON: What are the deadly sins in total?

There are seven deadly sins.

Let's see if I can remember them.

There's gluttony, lust, envy, greed, sloth, wrath, and pride or vanity.

Sins are actually a thing that we try to hide from each other, right?

It's not all fun and games and debauchery.

It's actually sometimes secret, something a little bit deeper, something a little bit more personal, perhaps.

And so what you can expect this evening is to have storytellers telling the whole gamut of sins.

Why don't we get started with you telling me what role storytelling plays in your life?

GALLAGHER: Well, I'm Irish, so I sort of think that has a huge factor in being a storyteller.

There's a long tradition, I think, in Irish storytelling and in my family, of finding humor even in very painful things.

And so I think that I attribute a lot to my family and my heritage for, for how stories have become so important.

But also, as a therapist, psychotherapist, there is, at the core of what I do is, I listen to people's stories.

OKOKON: Mm-hmm.

GALLAGHER: And their hope is that they re-author them into a different story that fits them better.

So I feel like both personally and professionally, I'm enveloped in storytelling a lot of the time.

OKOKON: Yeah, that's a beautiful way to describe psychotherapy, that people are looking to re-author their own stories.

GALLAGHER: Thanks.

OKOKON: Yeah.

So tonight's theme is "Deadly Sins."

How did that inspire you for your story?

GALLAGHER: Well, I think of myself as not a huge sinner, but an occasional, an occasional sinner.

And I'm actually fairly nice and even-keeled.

But there was a particular story that I had in mind when I though of the Deadly Sins-- the sin of wrath.

It's a really big emotion for me-- I don't tend to do it very often.

But this particular story, I do it in a very public way, which was... which was not my... not my intention, but it was my outcome.

OKOKON: Hmm, interesting.

GALLAGHER: As a psychotherapist, I see a lot of couples in my practice.

And it amazes me how much couples like to fight to win.

Like, they actually, like...

I somehow don't understand-- "If I win this argument or win this decision, "then this is really going to improve our relationship going forward."

(laughter) But secretly, I also really like working with couples, because it gives me a "what not to do" guide in my own relationship.

So I'll watch a couple fight and I'll say, "Oh, yeah, I do that, yeah-- I'd better stop doing that."

Or, "Oh, I should take a note-- that really worked really well in a fight."

So I'm not quite sure, when I'm finished telling my story tonight, that you will... you might have less respect for me, but I'm willing to take that chance.

(laughter) I didn't decide to take on a fight with my partner.

I decided to take on a fight with the United States Postal Service.

Yes, that quasi-governmental agency was my Goliath, and I was going to be the David that slayed it.

So to just give you a sense of what started adding powder to my keg, we all know the first line of questions, right?

Is there anything fragile, liquid, perishable, hazardous, flammable?

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Then the next round of questions-- do you need insurance, tracking, postage stamps, passport, groceries, a massage, a cold beer, you know?

The questions seemed to be somewhat endless.

But I wasn't prepared a couple of months ago when I went to the post office to mail a single-page letter in a business envelope, and I just happened to not have a stamp.

So I get the first line of questions, I get the second line of questions, then the poor postal worker gasps for air to come out with even more questions.

"Are there any lithium batteries or perfume in that envelope?"

Well, my sarcasm got the best of me, and so I took it and I went, "Well, I don't know-- "wouldn't that be kind of weird if there was lithium batteries or perfume in this envelope?"

Stone-faced, she said, "Sir, it'd be weirder"-- and I'm not sure that that's a word-- "It'd be weirder if there was perfume or lithium batteries "in that envelope and I didn't ask you about it."

So I had no idea what to do with logic like that.

But my Irish was up at that point.

So that was, like, on a Thursday.

And on Monday, I had to go to the post office to mail a "Reader's Digest" back to my mother who had visited for the weekend, and she wasn't finished an article in it.

I said, "You know, Mom, you can buy 'Reader's Digest.'"

And she said, "I like my own copy."

I said, "When you buy it, it is your own copy."

But you don't argue with your mother.

And so it was the first line of questions, it was the second line of questions, then the third line of questions.

Everything was going well.

"How do you want to pay?"

"Credit card," swipe.

"Can I see your card?"

"Sir, you didn't sign the back of your card."

And I said, "Yeah, I know.

"I don't know if it was, like, on NPR or I just read it online, "but I read that you shouldn't sign the back of your card, "because if someone steals your wallet, "they have your I.D.

and all your credit cards and multiple versions of your signature."

And he says, "Well, we are not allowed... We have to keep the card if it's not signed."

(mild laughter) And I said, "I can't sign the card unless you give it back."

(laughter) And we did this, like, eye thing for about ten seconds.

And then I lost it.

Like, my wrath was out of control.

I take out my wallet, I'm throwing my I.D.

and my credit cards and my cash on the counter and I said, "Look, you people, I work across the street-- "I am here two to three days a week!

"You all know me, don't you, don't you?

"Yes, you all know me.

"In fact, I've been using this credit card "for the 25 years I've been coming to this post office, "and no one has ever asked me to have it signed on the back.

"This is why you are going bankrupt.

"This is why FedEx and U.P.S.

are going to wipe the floor with you people."

And then I realize where I am.

Like, I'm in a downtown post office at noontime.

So I look around, and it's quite crowded, so I gather up all my credit cards and my cash and my envelope, and I scurry out the door before security came for me, because I was sure they were.

And I marched back to my office and got online, because I was going to prove that I was right, I was going to print it out, and I was going to walk back across the street.

Well, it does turn out you are supposed to sign your credit card.

Yeah, I guess it's like a loan document of some kind.

But it is not true that they can actually keep your card if it is not signed.

Well, a combination of pride and humiliation and embarrassment-- I couldn't go back to that post office for months.

Like, I just couldn't show my face in there.

And I started using the U.P.S.

Store, which is a couple of blocks further.

And I'm going in, mailing letters and things, and they said, "You know, sir, it's really expensive here.

Like, the post office is just up the road."

And I said, "Yeah, I can't go there."

I said, "There's trouble there, I can't."

"You got in trouble at the post..." "It's a long story-- I don't want to get into it.

Just...

I don't care how much it costs, just send this."

And then I thought, "I'm always encouraging my clients to do the right thing and to face their fears."

So I thought, "Maybe I'll bring a peace offering, like brownies, although they'll think they're laced with arsenic."

And I thought, "Well, there's those, like, Lifesaver books "that we used to give our teachers in elementary school-- that seems like a generic gift."

Anyway, I went with nothing.

I stood in line.

Nervous, nervous, nervous.

I get up to the counter.

The guy could not have been nicer to me.

I think he probably just sort of thought I had had a mental health breakdown.

And when I left, I thought, "You know, I'm really "no different than all the people that I see in my office "day after day.

"And I'm one of those people, like everybody else, "that will hang in for a win, even when there's evidence to the contrary."

Thanks.

(cheers and applause) ♪ ROSE: I teach STEAM.

So I teach science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics at an all-black charter school over in Dorchester.

But when I'm not doing that, I'm a poet and actress in Boston.

So I spend a lot of time on the stage in various capacities.

OKOKON: Oh, that's great.

What are your thoughts about the ability of stories to connect people across cultures?

ROSE: To me, this is the only way in which people around the world have ever really learned.

And learning should be accessible whether or not you're literate or not.

So when I think of storytelling, it's been the only way that people of all walks have been able to communicate, learn, share their culture, and hopefully change the world.

To me, it's been through storytelling-- a sharing space with stories.

OKOKON: Yeah.

So when you consider people who grew up, maybe, very differently than you did, how can they or couldn't they relate to your stories?

ROSE: They could always relate to them, because I believe that human beings relate.

I'm pretty sure if you're of my generation you watched "Reading Rainbow," you watched "Wishbone," you watched "Ghostwriter."

Storylines are everywhere, especially in art.

I'm pretty sure if you watch "Scandal" nowadays.

But this idea of being able to tell your perspective and be heard, I think it goes across any backgrounds, no matter whether or not you grew up in a suburb or grew up in the same setting I grew up in.

♪ I grew up in Roslindale on a dead-end street called Delford.

I was born in 1985, so I existed in Roslindale probably about the first 12 years of my life, and I would say it was a bit of a utopia.

A lot of people think of America as a melting pot in this time period.

No, my street was a tossed salad.

We had a little bit of everybody, and everyone brought their own flavor, their own style.

I learned about convergent and divergent boundaries from people who escaped these volcanic islands that erupted, from Montserrat.

I learned about Puerto Rican culture and that Puerto Ricans, some of them were black.

I was, like, "Oh, my God."

This was just all these learning experiences.

I was raised by Cambodians.

I had a little bit of everything in Roslindale, and it was perfect until a day in 1996, when Boston decided to drown a whole bunch of poor immigrants in Roslindale.

On this particular day in 1996-- it wasn't raining, it was drizzling, all right?

So doing what I would always do on Sundays with my brother, I decided that I wanted my bacon, egg, and cheese.

And being a little sister, my brother's, like, "You're going to go to the store to get the eggs."

I'm, like, "All right, cool, whatever, Josh, I'll do it."

So I go get my eggs, but the first thing I realize is, "Why am I hopping over puddles "to get over Washington Street to Four Brothers' Market?

All right, whatever, let me just get the eggs."

I head on home.

By the time I get home, I realize the water's starting to pool at the side of the sidewalks a little more.

The water's not going down, but it's really not raining.

This is kind of weird, but I'm just going to watch "Ghostwriter" and keep minding my business, all right?

Eventually, we start to hear the water, the dogs start to congregate on the third floor and howl, the cats start to pace.

Me being from Roslindale, growing up in arboretums, I know you trust animals, all right?

So I'm, like, "Something's wrong."

Eventually, I hear the sound of water-- sounds like it's coming from the basement.

Me and my brother, being the investigators that we are, go into the basement and realize that there's brown and black water pouring in from the back of the basement.

And it's coming in pretty fast.

Eventually, it opens the door, and we can't close the door.

So we're, like, "Okay, well, let's just call Ma."

Ma's at work.

My mom works in Cambridge-- "Ma, the house is flooding."

"Ashley, it can't be flooding-- I'm in Cambridge, it's not raining."

"I know, but it's flooding."

Within the next hour, there's a firefighter at our door saying that we have to leave on a raft.

This is Roslindale, y'all-- this is Roslindale, okay?

A raft.

"Ma, I got to leave on a raft."

All right, I'm just going to get the cats and the dogs and get on the raft-- the guy says, "You can't bring the cats and the dogs."

I said, "Well, then, you know, I'm not going."

I go onto this whole tangent, Noah's Ark, I'm not leaving, Punky didn't leave Brandon, I'm not doing it.

Leave me here, I'm going down with the ship.

One of my neighbors come over and said, "Ashley, get in this raft."

And this was back in the day when your neighbor could still, like, discipline you, so I said, "All right, I'm going to get in the raft and go."

I end up at the Roslindale Community Center, which is... at the Archdale Community Center, which is now the Menino Center.

And it's pretty fun, because this is where I play basketball every day.

I, like, get there, this group called FEMA passes me a hat, a flashlight, and a cot.

I'm, like, "I can play basketball, "my mother's not here-- this is great.

All right, this works."

Until my mother shows up with the cat in a bag, literally.

I'm, like, "Yeah, you saved my cat, Ma, you're the best!

But you smell like sewage."

She looks like... "All right, Ash, take the cat."

But my mom doesn't look like her normal self.

I'm, like, maybe it's because she's wet.

Once she dries off, she'll be back to normal.

"Ma, look at my... Ma, what's wrong?

What's going on with the house?"

She says, "Everything's under water.

We can't go back to the house."

I'm, like, "Well, Ma, we're at the gym, it's fine."

She said, "But..." My mom doesn't look normal at this point.

Like, I'm starting to get a little more worried, but we have four days at this community center.

On the fifth day, my friends called FEMA leave.

Little did I know they would leave us floating on faith forever.

After that, we had to live in cars, because the community center had to turn back into a gym eventually.

We lived in cars for two weeks.

Eventually, my mom, being from New York City, having no family, ended up breaking back into the condemned apartments, because we realized they'd flooded us with sewage.

So we could no longer live there, but my mom had nowhere to go, so she becomes a squatter.

We squat in this apartment illegally for seven to eight months until eventually my mom wins an apartment.

She actually wins a home off of watching TV for the first time.

It was... Oprah had a show on, a special called "Habitat for Humanity."

(applause) Right, clap for Oprah, right?

Love Oprah.

And I look at it, I say, "Ma, we should apply for this Habitat for Humanity thing."

She's, like, "Ashley, don't you realize I lose everything?

I just lost a house, I lost everything."

I said, "Ma, I just won the Easter egg raffle-- I win everything, all right?"

So we're both going back and forth.

I decide, "You know what, Ma?

I'm going to apply.

Because my English teacher said I'm a good writer."

The application comes, I apply.

Lo and behold, two weeks later, I told you so.

We got picked for the Habitat for Humanity house.

I'm like, "Yay!"

Now that's when we clap for Habitat.

(applause) Within one...

They spent one year, college kids, church missionaries, volunteers helped me rebuild a house that we now... my mom still owns and lives on on Hansborough Street in Dorchester.

I get a scholarship to college, my life's put back together.

I go back and make sure I help out for Habitat for Humanity when Hurricane Katrina hits, 'cause it's the cycle of giving, but I still hate FEMA.

(laughter) I hate FEMA-- I kid you not.

The wrath of revenge and hate that I have for them, it never left.

It actually didn't leave, I would say, until about two weeks ago.

I end up about to be able to perform at a special event, and I'm happy to go over.

They're, like, "Oh, Ashley, you're a poet.

I hear you write a lot about housing rights."

And I go into this whole tangent about being displaced and flooded, and this random guy in the audience stands up and says, "I'm sorry."

I said, "You are.

You are sorry for interrupting me like that."

I was, like, "What are you doing?"

He goes, "No, ma'am, I was on that team 20 years ago from FEMA."

I look at this man with the wrath of hate.

Every... it was a "Get Out" moment.

Have you guys ever seen "Get Out," when she stirs the cup?

I immediately start to... No, I immediately start to cry.

I'm, like, "You're from where?"

He says, "I'm from FEMA, "and I have to stand here and ask you for forgiveness.

"I was new, I was in my 20s.

I remember what they did to you, the Cambodians, the Lebanese."

He starts to name... he said, "Your street's the street with the..." We said it at the same time-- "The wall."

Roslindale, if you go from Forest Hills down, is a valley at first, if you know that.

Roslindale literally goes into a bucket.

There was no way you would escape.

And the one thing I had to look at, he said, "I didn't forget about your street, and I can't lie-- "over recent times when these hurricanes have hit Houston, "Tampa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, "I always say, 'I saw this early in my career, "and it happened on a street, on Delford.'

Will you forgive me?"

I look at him with the wrath of hate in my eyes, remembering the depression that my mom still hasn't left, remembering how we had no homes, how I had to explain to the Timilty School why I had no clean clothes.

How you never came back to save us.

I thought about, though, the fact that I got a scholarship to college, that Habitat for Humanity gave me the one thing I needed, that I thought I needed the most, which was a house.

And then I realized right then and there, God might have been working in the funniest ways.

I didn't need a house.

This man gave me the one thing that I needed for 30 years, and that was an apology.

Thank you.

(cheers and applause) ♪ OKOKON: Khuyen, it's great to meet you.

BUI: Yes.

OKOKON: And you're from Vietnam originally?

BUI: Yes, I'm from Hanoi.

OKOKON: Okay.

And is storytelling something that's common back home for you?

BUI: Yes and no.

Yes, because everybody tells story, especially at dinner, like, you know, big, like, family gathering, everyone talk about different story.

But the kind of story we tell, they are not, like, really personal story like this.

So there's a lot of like... you either talk about a third person, you talk about an event, or you talk about money, or you talk about land.

Which... none of those interested me.

OKOKON: What has storytelling taught you about listening to others, and has it helped or not helped in your ability to listen?

BUI: The quality of my story depends on the quality of the listening audience.

If an audience...

I give you, like, for example, if you play music at a very noisy bar, no matter how good you are as a musician, the music wouldn't be that good, because it's not good enough of a listening capacity of space.

OKOKON: Sure.

BUI: And so good storytelling must come from listening-- willingness to listen, that's one.

And then the other thing is, listening is a very powerful and I also say risky endeavor, because we... because when we truly listen, we risk, like, changing ourself.

OKOKON: Yeah.

BUI: And I mean, that's scary.

OKOKON: Yeah.

BUI: And also powerful.

And I think... that's something that I think we should pay more attention to.

♪ When I was 18 years old in high school in Singapore, I devour all these American self-help books.

And it was all about making myself a better person, from running faster to eating healthier to thinking more positively.

That was just, like, my whole life.

And so when I came to America, I was set to make the most out of my experiences.

And what that meant here is to manage time efficiently, and to become uber-productive.

(laughter) And how do you do that?

Well, you first have to start by knowing the time, because what gets measured gets managed, right?

So I have been religiously tracking my time using a notebook in my pockets.

But for a while, I just realized that it's really, really tedious and there must be a better way to do it.

So one day in my sophomore of four years, I found out an app on my phone that would allow me to track my time just using three simple steps.

First, you press the icon, second, you press a button, and then third, you log the time.

And that's it.

And better yet, at the end of the day, it would automatically produce graphs, colorful graphs of my day.

And as you can tell, I was so pumped.

(laughter) The first few weeks, I aggressively analyzed my data so that I can optimize my behaviors.

And, you know, at first, I started tracking in terms of 30 minutes to an hour, and then I got really greedy.

I, like, "What if I go more granularly, to, like, the minutes?"

And so my time log would look something like this-- 4:15, I would be snacking, 4:20, I would be doing push-up.

At 4:23, I would open the door for my housemate, and I would socialize with them.

At 4:30, I would, like, back to doing homework, and 4:40, I'd be distracted, I'd snack again, and 4:50, I'll be back to work, and at 5:10, I am so fed up, like, I'm, you know... (laughter) It was really fun.

I mean, like, I felt like I was more aware of my time, and I was making progress, and you know, at the end of the day, I look at the graph, these colorful pie charts, and I was just, like, "Oh, I can shave a minute here, and I put a minute over there, "and, like, I could eat in less time and then socialize less, read more."

Like, it was really neat.

And then so, yeah, after about a year, and maybe more than 4,000 minutes of doing push-up... (laughter) A lot, yes.

And I just started to realize there is, something's going strange.

Like I... it wasn't pleasant at all.

I felt like...

I felt like I was just enjoying it because it made me feel smart, but I'm not really doing anything to change my behavior.

And as you know, like, if people get addicted to TV or social media or food like that, I got addicted to tracking data.

And it was really addictive.

You know, I felt like I had a self-imposed ADHD of some sort.

(laughter) Like, I would just be, like, so obsessed with my time performance that I could barely concentrate on anything.

And it felt like, you know, when you cook rice and then every minute you open the lids to check whether, is it working?

And I was like that-- it was nuts.

And it was so addictive, I couldn't quit.

It felt like, one time, I pull out my phone, it felt like I just ate another sugar candy and then dopamine in my head, and, like...

So, one day, in my springtime, for the first and the only time in my college life, I stayed up until 3:00 a.m. to finish a late assignment.

And the assignment wasn't done.

I was working with a lab partner, and I was just so exhausted, I told him, like, "Screw all this,-- I'm going to quit, I'm going to sleep."

And I did, and the next morning, I woke up-- barely woke up.

I walked to my 9:00 a.m. class, like, math class, like a zombie, and I remember sitting in the front row, staring at the blackboard and just totally zoned out.

Exhausted.

And I started to cry.

I don't know how or what, but I remember I wrote down in my black notebook, and it was wet with tears, and... What the hell was I doing in my life?

Why did I make it so hard?

And it wasn't just about, like, the all-nighter thing.

I think it's also about, I'm just so fed up with, like, this whole managing myself, managing my time thing.

And it was, like, I... at that moment, I just did the unthinkable.

I pull out my phone, and I deleted the app.

(laughter and applause) I also deleted all the data that I have got and, you know, this...

I would have cried losing them.

I deleted all of them.

And that moment just felt like liberation.

It felt like I had built my own prison, I have fatefully imprisoned myself in this thing, and then finally I broke free.

And it was amazing.

The first few days after that, I felt like I was still rehabilitating myself to the normal, like, clock time or, like, yeah.

How many minutes I have left, things like that.

But I think I've learned a really profound lesson.

I was very productive, and I'm hopefully still productive, but I've learned... it really... the whole thing made me question my whole notion of time.

You hear everyone say it about, "Oh, you have to make the most out of your time," and I'm, like, "What does that even mean?"

What do you make the most out of time?

And it just goes to show how we just deeply believe in the idea that time is the most scarce resource, and that we are all individual capitalists trying to make, like, the highest return on time investment, right?

And I don't know whether that's true anymore.

You know, after my experience, I just thought that this whole, like, greedy for time, maybe it just masked my own fear of just having a meaningless life.

And I don't know if any of you are or will be facing that existential questions, but I have learned from my prison-breaking experience that maybe productivity is important, but it's not everything.

You know, I still have to ask myself, how do I make the most out of time, but I also ask the different questions-- have I really lived today?

Thank you for your time.

(laughter) (cheers and applause) ANNOUNCER: This program is made possible in part by contributions from viewers like you.

Thank you.

♪

Preview: S1 Ep14 | 30s | Sometimes our switch gets flipped and we lose control. Hosted by Theresa Okokon. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by:

Stories from the Stage is a collaboration of WORLD Channel, WGBH Events, and Massmouth.