Slatersville: America's First Mill Village

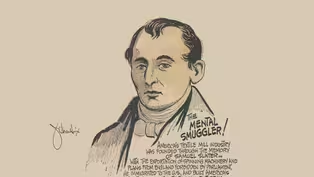

The Mental Smugglers

Episode 1 | 57m 32sVideo has Closed Captions

From Belper, England, to Pawtucket, to northern RI, the saga of Slatersville begins.

Our story begins in Belper, England, the birthplace of Samuel Slater, known as the “Father of the American Industrial Revolution” but a traitor to his native land. As Belper artists find ways to creatively rediscover his story, researchers dig up long-lost information on the man they label “Slater the Traitor." In Pawtucket, Samuel establishes a partnership with Moses Brown and William Almy.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Slatersville: America's First Mill Village is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media

Slatersville: America's First Mill Village

The Mental Smugglers

Episode 1 | 57m 32sVideo has Closed Captions

Our story begins in Belper, England, the birthplace of Samuel Slater, known as the “Father of the American Industrial Revolution” but a traitor to his native land. As Belper artists find ways to creatively rediscover his story, researchers dig up long-lost information on the man they label “Slater the Traitor." In Pawtucket, Samuel establishes a partnership with Moses Brown and William Almy.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Slatersville: America's First Mill Village

Slatersville: America's First Mill Village is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(downstream water whooshing).

(upbeat music).

- [Narrator] This was the old abandoned mill.

It stood right in this spot, in the center of my hometown.

And for half a century, most of it, had been left to rot and fall apart.

- I remember the old mill structure right in the center of Slatersville was a giant eyesore.

There's no other way to describe it.

- That was fallen down I'm telling you, it was an eyesore.

- I wouldn't say an eyesore but it certainly was not attractive.

And frankly, I didn't care (laughs).

It was not my problem.

- [Narrator] Growing up I knew next to nothing of its history or how people from the very village in which I was raised had impacted the world.

Then when I was 18, I started to film it.

Nobody seemed to care, so I just kept doing it.

And for reasons I couldn't fully explain at the time the buildings were drawing me in closer, and closer, and closer.

And the more I focused on it, the more I realized, I wasn't the only one.

- What drew me to the mill buildings obviously was the stone buildings.

And I remember watching that bell free as a kid begin to disintegrate and my mother would occasionally say, "One day, the bell's gonna fall."

And even as a young kid, I was going, "why is that being allowed to fall apart?"

- [Narrator] Whenever I filmed it, I was never brave enough to go inside, but Allan was.

- I was really appalled at the condition of the buildings.

- [Narrator] And at the time Allan was working for a company that was interested in purchasing the mill property for storage.

- In 2001, I decided to videotape it and I used an old VHS camera.

I was surprised to see that there were so many open doors and it was so accessible.

I went through every single building, all the floors, places where probably I shouldn't have been.

The roofs had caved in, the floors have caved in.

It looked like squatters had bit in there.

I was just blown away by how far those buildings have deteriorated.

I couldn't believe that that much history was going to be lost.

- [Narrator] These structures and the village that surrounded them had a name, Slatersville.

But what stories and influences were associated with this name, Slater?

what did it mean to our town?

Our state, across the country, or around the world?

And how did they make us who we are today?

And if those answers were so meaningful, why was a tree growing out of the fourth floor window?

- It was there and then the trees grew through it.

- The level of deteriorate like this, it's something I can't answer.

Apparently no one had the fortitude to say, "Hey, this is what we are gotta do because of the fact there's so much history."

- They represent what Slatersville was.

(mellow music) - It was just one more thing that you're losing you might just say.

And sentimentally, it did have a lot of meaning because it meant so much to so many people who lived here, for years and years, There sons and daughters worked there too.

- [Narrator] Time was running out and the saving of the Slatersville's mill buildings had finally become a priority.

- It's in such bad shape now that I don't know what you can do.

- [Narrator] And that's why people in the town were holding meetings, several, and I showed up to film a few.

- Please come forward to the podium, identify yourself.

- [Narrator] But by 2005, there seemed to be two groups of people.

Those who had the power to save and repurpose it and those who are advocating for more creative ideas, who did not.

- This property has sat here for years, and years, and years and nothing has happened.

- [Narrator] And whether it was a neighborhood brainstorming or a public hearing, those whose families had worked in the mill, who proudly had deep roots in the town, showed up and made their voices heard.

- And so that story needs to come out.

And I think that people who are living and making their lives in a place like Slatersville needs to understand the role that they play in a process of 200 years.

- [Narrator] But even as I was filming all of this, there was so much that I did not know.

- These buildings have a reason for being where they are.

- [Narrator] And there was a lot, as it turns out.

They didn't know either.

- What we see in a place like Slatersville is the creation of a community around an idea that becomes a space where you bring in.

It's the story of immigration.

It's the story of ingenuity.

It's the story of enterprise.

And it's all right there in one community.

- Samuel Slater came up here, you know.

- [Narrator] So it was clear that I needed to go back.

- I mean the history goes way back.

- [Narrator] And I mean way back.

As in, before there was even a decrepit building to save, and to find out why it was worth saving.

And after years of research and connections made around the world, the story that we uncovered, surpassed anything that was ever anticipated.

But it was my eighth grade geography teacher who put it best.

- Without knowing where you've been, how can you gauge where you're going to go?

(upbeat music).

(mellow music) - The Blackstone Valley is important because it's what brought America to the greatness that it has today.

Now, everything has a beginning.

- [Narrator] On April 5th, 1790, a young man from England formed a partnership with merchants to build the first cotton mill in America, located in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

The ripple effect of his actions will forever changed the landscape of industry in the Blackstone Valley, across America and throughout the world.

He would go on to build a fortune and he would become heroically branded as father of the industrial revolution.

Which is what we Americans were taught.

But we never heard what the British thought of him nor had Bob Billington, when he began his job in the mid 1980's.

- While you're on this mission of trying to promote the Blackstone.

You look for collaborators, you look for any little piece of connection that you can have with people.

(upbeat music) - [Narrator] In the year 1789, a young man set sail from England for New York.

- [Woman] His name was Samuel Slater.

I tried to pick during the 66 long days it took him to cross the ocean.

Terribly homesick for his native England.

He never got over that feeling, yet he never went back.

- In 1992, we wanted to try to figure out this relationship betwe- Samuel Slater leaving England, coming here.

And we thought, if we can only figure out where he lived.

It kept going down from region to region and finally ended up in a place called Derbyshire, which is a county in a little valley called the Amber Valley.

And then the phone call came into a man named Bridge Whitworth who was the head of culture and recreation history.

Had a great conversation with him about what he knew about Samuel Slater.

- I worked at the office of my chief officer, and I were asked, what do you know about Samuel Slater?

And my answer was, "Who the heck is Samuel Slater?"

- I grew up in Ripley, which is the next town along from Belper in Derbyshire.

And I've always been fascinated by history.

So it was always strange to me when I moved over here with everyone's fascination, with Samuel Slater.

- [Narrator] What was the big deal about Samuel Slater?

While his story may be over two centuries old, our understanding of history is always evolving.

But for the people of Derbyshire, the name Slater, has always had a bit of a rhyme to it.

- Did you get Samuel Slater school?

- No.

- I think he was possibly written out to the history 'cause he was a traitor - He's known as Slater the traitor.

(woman laughs).

- He was a traitor.

- Actually in law he was a traitor.

- Slater was the Benedict Arnold of Derbyshire.

- [Narrator] While its citizens were becoming reacquainted with Samuel Slater in the 1990s, his story was told through a variety of art forms, in projects commissioned by the Belper Town Council.

And the first of these projects involved a trio.

- My name's Barry Coope.

- I'm Jim Boyes.

- I'm Lester Simpson, and we are Coope Boyes and Simpson.

- Well, we were asked by the administration of Belper, to do a millennium project about the town itself.

So it was going to have to figure in the millennium suite that we did for Belper called "Where you belong," And it fell on Jim to write, "The Ballad of Samuel Slater."

- I'd never heard of Samuel Slater.

Now do I like him?

I don't know.

He was very interesting, and in some ways, a little bit devious (laughs).

- We knew each other and we knew each other's work.

When we sang together, it was one of those magic moments you think the sum is greater than the parts.

We actually realized that we made a good sound, which was very pleasing.

I think, wasn't it?

- Yes.

- Absolutely - Yeah.

♪ Oh, I was raised a tall the house ♪ ♪ in Black Rock I was born ♪ ♪ Near Belper town in Derbyshire ♪ ♪ I learned to sow the corn.

♪ ♪ I quickly gained the labourer's skills ♪ ♪ And the sun upon me shone ♪ ♪ For my father found water for the mills ♪ ♪ And the land to build them on.

♪ - So what is there not to love about Belper.

it's so rich.

It's history is amazing, culturally, socially, architecturally.

- Yeah, like you can see all the mills on the sign here.

Can you see Strutt's Mill, Arkwright Mills, Smedley's Mill - Peter, Hi.

- How are you.

- I got a baby banner in the cast chamber.

- [Narrator] There are some massive, really important globally significant stories here.

- So when they did the research, they said, "Gosh, we've forgotten about Slater, Slater may be a big deal to the Americans, but he's nothing to us.

- [Narrator] I love to be able to show people how the world changed because of what happened here in Belper in the Derwent Valley.

- Strutt and Arkwright they're the heroes of this type of work.

- And it resonates.

In Slatersville, of course it does.

- [Narrator] The British industrial revolution began in the 1760's decades before it reached America.

By this time England had established its empire across the world, creating global systems that brought unprecedented wealth to the country and set off the political and economic shifts that fuel industrialization.

Textile production was the first area to be widely mechanized.

The ancient process of spinning thread by hand was to be replaced by a water powered machinery, an inventor and businessman named Richard Arkwright, led the way in patenting and implementing technologies for the new factory system, including the spinning frame, carting engine, and other creations.

Jedidiah Strutt was a wealthy businessman in Derbyshire.

Richard Arkwright came to him, seeking an investment for the creation of a new water mill.

- This says Derwent Valley Mills.

- Strutt is the link between all the sites in the Derwent Valley, World Heritage Site.

I have now spent 24 years really studying the strokes.

Oh, terrific.

Because after all, without that achievement Slater could not have done anything.

So the partnership built the mill of Cromford because they decided to use water power.

And Strutt was already using water power.

Five years later, on his own initiative, Strutt began buying land here at Belper and built his own mills.

- [Narrator] Arkwright and Strutt didn't just introduce machines and water power.

They also transformed this landscape through vast systems of social control that would come to dominate mill workers' lives and the lives of all workers to come.

In these new factories, workers no longer labored on their own terms.

They didn't grow their own food or produce their own goods.

They worked on the owner's machines to produce someone else's goods.

The factories employed children, institutionalized work for wages, find and disciplined their workers, set labor to an hourly schedule, and instituted constant oversight and workers did not passively accept it.

Protest and rebellion were common.

Historian Andrew Yeah was a proponent of these measures.

- The main difficulty did know to my apprehension lies so much in the invention of a proper self acting mechanism for drawing out and twisting cotton into a continuous thread.

As in, draining human beings to renounce of the solitary habits of work and to identify themselves with the unvarying regularity of the complex automaton.

To devise and administer a successful code of factory discipline, suited to the necessities of factory diligence was the actually enterprise, the noble achievement of Arkwright.

- This was the beginning of the industrial capitalist system, created by countless individuals across the British empire that would for better or worse, forever change the world.

And right in the middle of all this, there was a teenager named.

- Samuel Slater.

- The Americas.

- [Narrator] Who was either hated or forgotten.

- Because he left under penalty of death.

- [Rosemary] I didn't have the information to start with.

I only had the knowledge that Samuel slater was famous.

- One little boy who worked in the mills in Belper and Milford went to America and he became very famous.

- I thought, oh, that's a good story.

That's a good story of a young chap who went out to America and became famous, the father of American manufacturing.

And I thought, "Oh, I could tell this."

- There are six children in the family of William, old cook Slater and his wife Elizabeth.

Isn't that right Lizzy?

(upbeat music).

- Now there are seven.

- Samuel Slater.

The man who would bring this British industrial system to America was born in Belper in 1768.

- Samuel I'm prepared to grant your request for a charity apprenticeship with our new mills at Milford, under the following terms.

- Samuel Slater was an employee, he was apprentice to Jedidiah Strutt, which is very, very important because Strutt was one of the most progressive of all the mill owners.

- And he hired young Sam Slater, a teenager.

And Mr. Slater learned everything about the mills and not just the technology behind it, but all of the sociological economic aspects of it.

- And that's the story that I was going to tell.

And then I met Stephanie.

- Right.

Everybody, we will be having an opportunity for an informal chat afterwards, but at this moment in time, we have three representatives of the Slater study group.

- I'm Rosemary.

- We've learned so much because we are both studying the same subject on different sides of the Atlantic.

So we've done this through the years and we do the same thing when we go there, try to learn a little bit more about how they preserve buildings, how they tell their stories.

- So Slater, we've lived with Slater for- - Long time.

- Quite a long time.

(group laughing) - I'm Stephanie Hitchcock, researcher.

I have done a lot of local research and became involved with the film and the book.

And I'd also like to mention Griff, who can't be here tonight and was one of the group, three women and a man, we drove him crazy.

Was he a hero or was he a traitor?

Depends which side of the Atlantic you come from.

- So we sparked maybe some controversy, a little bit.

- History is history.

You can't alter it and you shouldn't alter it.

- They had to go back and research their history.

We were trying to research our history.

- I am very passionate about always going back as far as you can to source documents.

And I think you should tell the truth.

- And the Slater study group set out to tell that truth in a short film.

- People came and took part.

We were about 200 people all together, involved in research and writing, making costumes, just working out on a hopefully film.

- The story is not very well known here.

- Right.

- He was a traitor.

So anybody who was related wouldn't admit it (laughs).

They were think, "I don't want to be related to him, I'm not going to talk about him anymore (laughs).

So his story didn't really come out.

- Was he a traitor?

Was he a hero?

Or was he both?

Is it black and white?

Or is it 60, 40?

Who knows?

- [Narrator] In the late 18th century, countries attempted to promote economic development through the control of markets and information.

In the case of England, their government did not want other countries building factories that would compete with their industry.

Patents and machine designs were jealously guarded and protected by law.

The United Kingdom had strict rules about the sharing of industrial secrets with other nations, even prohibiting the immigration of skilled mechanics out of the country.

All of these generated the backdrop for the dramatic conflict that was about to unfold.

- And it is the law of the land I know, I know.

It is prohibited, even treason.

- It is indeed.

- Today the roots of this story have inspired theater producers to create a compelling new work for the stage.

- So the research started and soon I discovered that there was enough material there to provide us with a really good play.

We were also able to think about the legacy that Slater left.

- Good evening.

Let me introduce myself.

I am the inquisitor.

My role, my part in life's drama always is in the end to find the truth, or somebody's truth anyway.

- [Narrator] But what was the truth and why to this very day, is it even questioned?

- I did read an early book that was written about his life.

And let's say it has a lot of spin in it.

- [Narrator] The memoir of Samuel Slater, father of American manufacturers was published in 1836.

And for far too long, it served as the only source of information in the telling of this story.

- Facts about Samuel Slater, all come from a book by George White and it was published just after his death.

Look at the back of the book, if there's no reference to source documents, start asking questions.

And if you don't want to ask the questions, throw it in the bin.

And I think that's very true about White's book.

- Because I do think it's easy.

If you go where no one knows you to reinvent yourself.

And I think some mill did a bit of that.

- [Narrator] And we also think the author might have done a bit of that.

Canterbury, Connecticut, 28th of May, 1835.

"Sir, I'm preparing a memoir of Samuel Slater, the father of American manufacturers, and in connection with the history of their rise in progress in America.

As I intend to answer the objectives argued against manufactories, or the score of increasing vice, ignorance and poverty.

I have no doubt that a true representation of the present state of manufacturing villages will fully remove these objections.

Anything that you consider interesting on the subject and will aid my design, I should be happy to receive.

Yours respectfully, George S. White.

- From my perspective, a book published in 1836, this is when America was looking for heroes.

This is part and parcel of just creation of an American hero, creation of an American literature.

Because if you read that book, it's dedicated to Andrew Jackson.

- I understand you've taught us how to spin.

So's to rival great Britain in her manufacture.

- With Samuel Slater coming to America, bringing this knowledge with him.

I don't think he ever felt guilty about it.

I think that it was all fair game to him.

- Yes, sir.

I suppose that I've given out the psalm, and they've been singing to the tune ever since.

- I think that was a nice little dig at the British.

- I can think of but one title for a man with your amazing records, sir, the father of American manufacturers.

(upbeat music).

- [Narrator] Not exactly.

- With regards to Samuel's early life, White couldn't do any research 'cause he's in America.

So he had to rely on what Samuel told him.

I'm biased.

I'm from Belper.

And I say, Samuel lied.

There are some points in White's book that we specifically picked out because we knew we could find documentation.

Never easy to find documentation, and we weren't all over the country.

- [Narrator] So where was Samuel Slater born?

And why might he have wanted his biographer to alter that information?

These are the remains of Holly House in Blackbrook where Samuel Slater was believed to have been born.

George White claimed that Samuel's father, who died in a tragic farming accident had owned this land and its property.

- I William Slater of Belper in the parish of Duffield in county of Derby, Yemen and farmer, do make this my last will and Testament.

- [Narrator] But the Slater study group learned that was one of many false claims made in White's book.

William was a Yemen farmer, which meant due to English law at the time that he could not have owned any land or property, which also meant that Samuel was born somewhere else.

- We searched for the land and finally found it on what is now known as Chevin road in Belper.

- There was a blue plaque.

In England we have blue plaques that are displayed on the side of buildings.

Passed by one day and I looked up and thought, "Samuel Slater?

I've never heard of Samuel Slater.

Who is this guy?"

- Before I begin I'd like to thank the work of Stephanie Hitchcock in the producer, director of the film.

Who uncovered the real history of Samuel Slater and led us to this very location.

- [Narrator] Which would mean this opening lyric from The Ballad of Samuel Slater, recorded several years before this discovery was made.

♪ Oh, I was raised a tall the house ♪ ♪ In Blackbrook I was born ♪ - [Narrator] Might not be so accurate.

- And so we knocked on every house, didn't we?

- We did.

And we said, "Can we see your house deeds please?

Because we want to find out who owns this land.

- Certainly the path to get to this point in history has been a long one.

I'd like to thank Rosemary Timms of Milford.

Yes, around applause for Rosemary.

(crowd applause) Who nominated, brave enough to nominate Samuel Slater for the blue plaque.

- And so that was the cottage.

- Yeah.

- And it was just single storey.

- When they were trying to put the blue plaque up outside his house, I knew there was some resistance to acknowledge someone who had in many ways done a disservice.

(crowd applause) - And if you just look for the part for me.

♪ But then when I was 14 years ♪ ♪ A apprentice, I was bound ♪ ♪ To Jedidiah Strutt's fame had grown the country round ♪ ♪ To build machines and see the way ♪ ♪ Those mighty mills were wrong ♪ ♪ But father died in tragedy ♪ ♪ At first that I be gone.

♪ ♪ I read in the Philadelphia news ♪ ♪ And I heard of the great campaign ♪ ♪ I knew that the Belper and Milford mills ♪ ♪ Would never be built again ♪ ♪ Rich bounties lay across the sea ♪ ♪ Where cotton was spun by hand ♪ ♪ To recreate an industry ♪ ♪ In a far of distant land.

♪ - [Narrator] Over the six and a half years, he was indentured to Strutt.

As Samuel grew to be a young man, there was a whole other world on the other side of the ocean that he would someday enter.

Welcome to Rhode Island.

- Much of Rhode Island's history, which is, and I know I'm biased, but I have to say is absolutely extraordinary.

Is not understood by locals and it's not understood and appreciated in the academy.

And it is in fact, the least written about of the original 13 colonies.

This topic is not the only important Rhode Island topic that is unknown and underappreciated.

Our charter becomes the basis of so much of the founding documents of the United States.

So much of that, not just the actions, but the philosophy begins here.

- Rhode Island had a pretty diverse economy, a lot of maritime activity.

You had industrialism popping up and individuals working in factories and distilleries.

So it was pretty diverse economy and a pretty wealthy economy.

- Rhode Island in the 18th century also had a large number of enslaved people within the state, right?

So it varies by decade, but we're looking at some 10% of the population throughout the 18th century was enslaved.

Enslaved people are an important part of building this Rhode Island, artist and economy that makes Rhode Island such a good place to then have these first factories.

The first part was Rhode Islanders provisioning, British sugar plantations in the West Indies.

Rhode Island traders are taking molasses from those sugar islands in the West Indies, bringing that molasses up to Rhode Island where they're distilling it into rum, taking that rum and now bringing it directly to the coast of Africa, where they're trading that rum for enslaved people, bringing those enslaved people back to the West Indies, trading them for more molasses, which then comes back up to Rhode Island.

So you have this three point triangle trade.

And Rhode Island becomes the biggest player in British North America, in this triangle trade, in the transatlantic slave trade.

So far more than any other colonies.

- [Narrator] Meanwhile, back in England.

- Samuel!

Can you take a look at this?

- Slater probably could have been a paid hand, an overseer, a superintendent, but he didn't have the capital to start.

He had the knowledge, that is what he had.

And there were so much information in England about Americans wanting someone with knowledge of the Arkwright system.

- And then from the 1st of September, 1789, just two months after completing his apprenticeship, the 21-year-old went home.

- I washed my clothes.

- [Andrew] Told his mother he was going to London.

- I have some business in London and must catch the flight from Derby this evening.

- He'd probably never left Belper.

He'd not seen anything.

I doubt if he'd even been seven miles to Derby.

And of course he didn't even tell his mother he was going.

- When will you be back?

- My dear mother, this note is to tell you what I could not say before.

- I'm sure she was worried sick for a long time because he wasn't worldly wise.

- I am bound for America.

I know my going so far away will grieve you and I'm sorry for it.

- He mentions the British government really searched everyone who was leaving on a ship to America.

And the only thing he had with him were his apprenticeship papers.

If that's true, I have no idea.

- But to bet in my life, I must hide my trade.

- And so supposedly he went in disguise as a farm boy.

- [Narrator] By leaving the country and bringing industrial secrets to America, Slater was violating the law and potentially harming industry at home.

Worse, he was delivering industrial secrets to a new country, the British had just fought a war against, and lost.

♪ Dear mother as you read this note ♪ ♪ I'm journeying far away ♪ ♪ On a sailing ship on the raging main ♪ ♪ Bound for the Mary Kay ♪ ♪ Oh, don't you worry mother dear ♪ ♪ For I am safe and well ♪ ♪ And fortune will shine mother have no fear.

♪ Your loving son, Sam, you well.

- Imagine when he arrived in America this vast fast space that he'd no idea about where which begin.

- [Narrator] Upon arriving in New York city, Slater searched for someone who would hire him for his specialized knowledge.

He was not successful, but he would not be sticking around New York for long.

- Friend I have received thine of second instant and observe its contents.

I, or rather Almy and Brown who have the business in the cotton line, which I began.

One being my son-in-law and the other kinsman want the assistance of a man, skilled in the frame or water spinning.

An experiment has been made which has failed.

As the frame we have is the first attempt of the kind that has been made in America.

It is too imperfect to afford much encouragement.

We hardly know what to say to thee, but if thou thought thou could perfect and conduct them to profit.

If thou will come and do it, thou shall have all the profits made of them over and above the interest of the money they cost and the wear and tear of them and have the credit as well as the advantage of perfecting the first mill in America, we should be glad to engage thy care so long as it can be made profitable to both, and we can agree.

I am for myself and Almy and Brown thy friend, Moses brown.

- Moses Brown is a person who became wealthy because of slavery.

His family built their wealth upon slavery.

And for whatever reason, whether it was a religious experience or just looking around him and sensing the moral injustice of slavery, he decided to put his money behind abolitionism.

- [Narrator] And because of that, there's a high school named after him today, but- - He's doing this abolitionist work at the same time, he is founding these cotton factories that are directly and materially supporting slavery because they're buying up this southern Kari and he's helping to create the actual demand for cotton and the actual demand for slavery.

- Places where you could tap falling water in convenient locations were very valued.

Pawtucket Falls, had a lot of falling water and it was on tide water.

That is where Samuel Slater is brought by Moses brown.

- [Woman] Soon after Samuel arrived in this country, he went to Providence to see Mr. Brown.

- [Mr. Brown] So Tell me Slater, these Arkwright cotton mills in England, they must be something.

- [Slater] Oh, yes, they are sir.

Quite something.

- [Mr. Brown] You worked for these fellows Strutt and Arkwright for some time.

- [Narrator] While the story may have been heroically spun for generations, Stephanie Hitchcock believes that Samuel continued to make his false claims with help from his biographer.

- Throughout the whole book, Arkwright keeps being bought into it.

And I think this is because the Americans originally knew about the Arkwright machine.

And I think in one part, he says that he had conversation with Arkwright.

Why would a 40 and a half year old trade apprentice, talk to someone who had been knighted, who lived 10 miles away, and had no financial control at all in Belper mills.

- [Mr. Brown] You claim you actually build one of these machines.

- [Slater] with no trouble, sir.

- [Mr. Brown] Oh, you have the plans, design, patents.

- [Slater] No, no, no.

You can't take plans or patents out of England.

- [Mr. Brown] Then how embrace this?

- [Slater] I've memorized everything.

- [Mr. Brown] Memorize?

- [Narrator] When the two men met Slater needed to provide proof of his experience to Moses Brown.

The first critical sign of this proof would come in the form of his indenture, a pasted together version of which George White included in his book with some glaring omissions.

- In White's book, there is a very good image of the indenture.

However, there's missing this big gaps in it, which didn't make sense.

- [Narrator] This is the actual indenture provided by the Smithsonian Institute.

- So I've blown this up and guess what?

Four lines have been taken out, four very important lines.

- [Narrator] It's hard to read all of what has been crossed out, but what we can make out, is that Samuel started to work for Strutt at two pounds and two shillings a year.

And that every two years he would get a raise, but who would cross this out?

And why?

- Jedidiah Strutt he would never, ever have signed a document with crossings out.

Whatever it is hidden, Samuel did it.

And I think what is written there was not good for the things that he pretended to be when he got to Pawtucket.

I think this is why he had this power over Moses Brown.

- Moses brown just wanted to hire him, to build the machines in the factory.

He said, no.

- He could build those machines and he wasn't gonna do it for nothing.

- He said, I wanna be a partner.

You supply the money, I'll supply the knowledge.

- [Woman] Suddenly the cotton mill was finished.

All it remained to do was test the machinery.

I stood with them a little frightened.

- [Mr. Brown] Sam blessed me with this machinery of yours is a quiet looking monster.

Ah, she's beautiful.

And we're supposed to believe it'll work.

- [Slater] It will.

- [Mr. Brown] At mess wire metal and wood, will spin cotton?

- [Slater] Yes, sir.

- [Mr. Brown] Show me.

- [Narrator] Oziel Wilkison, was a skilled blacksmith, who ran a shop making anchors for Rhode Island's merchant vessels.

And so Venice Brown was a skilled carpenter and pattern maker.

- You had the artisans there who could take the mental specifics that Slater could provide and translate it into physical reality.

- [Narrator] This is a painting of Samuel Slater presenting his first cotton spinning machine to Moses Brown.

At the feet of Brown, is a depiction of a slave known as Prime or Primus Jenckes.

- The Primus Jenckes was an enslaved person who had been trained and been working as an artisan.

He had been enslaved by the Jenckes family or this prominent artist and family.

He worked directly with Sam Slater and so Venice Brown, and the Wilkinsons on the construction of this early machinery.

- [Narrator] African Americans, who played critical roles in the birth of the industrial revolution in America were never properly acknowledged.

- But what we have here is a model water wheel.

You have your river over here and you would be lifting the gate up and you see the water, how it goes into the buckets.

And there's your gears working.

Water power, yay!

Only we're using electric to get this one going.

The water wheel's moving opinion wheel and then it moves the bevel's gears here.

What I'm doing is just rotating the wheel.

It's very dangerous if you don't know what you're doing, get your foot stuck in here and it can pull you in and crush.

You're gotta be very careful.

- [Narrator] We were all very, very nervous.

As Samuel walked away from us, I watched him pull back some levers.

- [Mr. Brown] My glory, boy it's working.

Sam, Sam you've done it boy, We've got a cotton mill.

- So while you're working upstairs on the wooden floor you got a vibration on.

So it's always feels like there's an earthquake going on here.

Very loud upstairs.

A lot of the workers would, you know, lose their hearing and have bad hearing as the years by too.

- This is the Throstle Machine, and it's named after the Throstle bird because of the sound it makes while it's running.

- Child labor of course was there from the beginning.

- The people who worked in factories from the beginning were not always seen as the cream of society.

That oftentimes manufacturers would go out and they would gather in people, who in many cases had children.

- They were called Pauper apprentices, young children taken from orphanages or poor families and apprentice to artisans.

They did not learn a trade, but rather performed repetitive work on machinery.

After housing and feeding them was found to be too costly.

Slater turned to employing young children and paying them hourly wages.

Children between six and 14 were paid between 30 and 60 cents per week to labor in dangerous conditions.

And the boys were paid more than girls.

Children were used simply because they were cheaper.

And because mill owners believed them to be easier to manipulate into obedient workers.

- There would be like kids running back and forth.

There wouldn't be just one machine, you're talking about a bunch of machines all the way down in this mill.

On both sides, these kids are gonna run around.

And when these are filling up, they're going to have to take the full ones off and put the empty ones on, so they're constantly doing that all day long.

So they got to put their fingers in there all the time from sun up to sun down, working with only a thirty-minute break.

- They'd lose digits, they'd lose their hand Maybe an arm, they'd lose their life.

- All he needed were hands, children.

He did not need their parents.

And yet he brought the whole family under the control of the factory.

- They were so close together that an adult couldn't get in there between them.

So they'd send these little rug rats, you know, inside to get a piece of broken twine and tie it back up and then throw the spindle up, or get outta there while you was still alive.

- But just like in England, people did not quietly accept this as the new normal.

Parents pulled their children out of the mills in large numbers.

They created work stoppages to demand higher wages, or to protest egregious conditions.

As a result Slater and his partners faced severe labor shortages and still workers rebelled in other ways too, such as theft or occasional arson.

- I've seen the payroll from slaters' mill, and you'll see kids that have five or six of them with the same last name because it was almost like a bonus.

If you brought your younger brother or sister in once they hit six or seven, you know, they pay you a little extra.

- [Narrator] So what did they do?

Almy Brown and Slater sent agents out to recruit poor families to mill life.

The more these people were cut off from an agricultural life, the more solidly staffed their mills would run.

- What you now see is two systems clashing.

Almy and Brown were accustomed to mercantile activity with Slater it's not task oriented, it's time oriented.

You all have to be at the factory at the same time.

Workers have to be paid.

They have to know when they're going to be paid.

You can't just say, I'll wait for six months.

Slater threatened to shut that factory down and protect it several times.

"My workers come around me daily, when am I gonna get paid?"

And Slater would approach Almy Brown and say, "If you don't pay these people, I'm just gonna tell 'em to go home."

And that was Almy Brown and Slater.

It was never a friendly arrangement.

- [Narrator] Throughout the 1790's, new mills and businesses had begun to surround Slater mill, which became a huge problem for several reasons.

First, their mill had become landlocked by companies who also relied on water power, which severely compromised Almy Brown and Slater's productivity and forced unwanted competition.

These companies also cut into their labor.

Knowing that Samuel had always struggled to control his workers, his situation was quickly becoming chaotic and unstable.

All of this was happening as they forged ahead in expanding operations.

But these problems were just getting worse and worse.

- [Man] What's that?

What was that?

- [Woman] Someone has thrown a stone through a window, outside the mill, a mob of angry men and women were gathered.

- [Worker] All right Slater, you had your warning.

- [Slater] I wouldn't come any close here manly.

- [Worker] I told you what we do.

Now we're going to do it.

- [Slater] Destroy anything, and we'll build it again and use solders will guard it.

- [Worker] We're not scared.

- [Slater] So listen to me all of you, the machine will give everybody a job.

I want to teach you how to run it.

Where we'll produce more cotton in one week than you've seen in a lifetime.

- A breach occurred in 1800 and Samuel Slater wanted to go out on his own.

And so did Almy Brown.

So they separated.

♪ I married a Blacksmith's daughter fair, ♪ ♪ In Pawtucket where I did stay.

♪ ♪ Her father helped make the machines ♪ ♪ Which earned us both a pay ♪ ♪ For many years we labored on ♪ ♪ And so our skill was grown ♪ ♪ And 1700 in 98 ♪ ♪ We branched out on our own ♪ ♪ Through good times and bad ♪ ♪ The mill still grew ♪ ♪ And the history books all say ♪ ♪ That on American industry ♪ ♪ Was made the slater way ♪ ♪ The slater way was growth but fair ♪ ♪ As the workers would testify ♪ ♪ Bought food and shelter and schools were there ♪ ♪ In plentiful supply ♪ ♪ And though I made it enormous wealth ♪ ♪ From those I did employ ♪ ♪ I worked as hard as them, myself ♪ ♪ Those comforts to enjoy ♪ - Slater Mill, Pawtucket is really what is brought to each and every child, an opportunity for visiting.

But that's really the only thing that's spoken.

It's just that history and it really doesn't go beyond that, not that I could ever see.

And still to this day, I find if there's any visiting, it will be the mill in Pawtucket.

And that's pretty much where it ends.

- [Narrator] But on the American side, that's where our story of Slatersville begins.

- What I do understand in family record is that Samuel sent letters.

Specifically to his siblings and asked them, will you come to America and join me in the success?

- Hello, Samuel.

- (laughs)John.

- [Narrator] John is the only one that we know that comes to America and takes that opportunity.

- [Narrator] That's right.

The father of the industrial revolution had a little brother, who in some areas was a bit wiser than his older brother.

- My great grandmother, the woman this house was built for, was the granddaughter of John Slater.

- My connections to the Slater family comes through my father.

He was William Slater Allen.

I am a direct descendant of John Slater.

- [Narrator] But John wasn't the only one, there were at least two others that we know of.

- (indistinct) - Isn't that interesting.

- Yeah.

- And I don't know who any of these people are?

Obviously they're part of the family.

- Native of Belper, England.

George A. Slater.

So was that was another brother?

What's then date?

It would be 1791, wouldn't it?

- Yes.

- Yes.

- We didn't know that.

Did we?

- [Narrator] There was A. George Slater, buried in Webster, Massachusetts, and his cousin, Mary.

But she wasn't the only Mary either.

- My name's Karen Haseldine.

My maiden name was Goodwin and I'm a Slater descendant.

I just think it's amazing that we've just driven a flown I mean, from Belper and now we're here standing by John's Grave.

My four times great grandmother Mary Slater, was the cousin of John.

She was born within a few months of him.

He's born on Christmas day.

- [Narrator] Karen is referring to a different Mary, born the same year as John, the same John who would run Slatersville.

This is part of the Slater family tree, as it was known in the 1950's.

Since the 18th century, many of the same names have been used, a lot.

There have been at least 26 Williams, 21 Johns, 14 Samuels, 13 Mary's, 11 George's, 10 Elizabeths and a whole lot more.

So for the sake of our story, we're sticking mostly with John and Ruth Slater and their family line because they both ran Slatersville.

The rest of Samuel's brothers were much older and had no experience working in a cotton mill.

Samuel was eight years older than John born on Christmas day, in 1776.

And he was the only sibling that Samuel would've truly needed for his next big move.

- [Slater] This one mill can't meet to demand.

We'll need all the mills we can get.

If we want to put American cotton on the world market.

- The mill village was an accommodation with the reality that the textile industry had to chase water power.

And water power was found out in the countryside up the rivers.

- Samuel was the machine man.

John had the expertise to read a river and determine where to put a dam, to get the best head of water coming over it, to provide power for a mill.

That was really his expertise.

- Since you've been in lodging's here, we've seen nothing of you for months.

- Know.

- And that's why he later persuaded his brother John, to go over.

- I'm trying to raise the arm to the body.

- And Samuel needed John.

- Let me look, perhaps I can help.

- He desperately needed John.

He was looking for a site with water that he could harness to power those water wheels, to power the machines.

- [Narrator] The two brothers traveled Northwest of Pawtucket to an area known as Smithfield.

They found a small Hamlet of sorts with a few people living along a river that had branched off from the Blackstone.

The place had a most unsavory reputation.

The missionaries who would visit from other parts of Rhode Island and the surrounding colonies described it as ungodly.

A Haven were criminals and other undesirable characters would hide with heavy amounts of drinking, gambling and immorality.

And it was this place where they would build the largest mill in America and control everything surrounding it.

Right in the middle of nowhere.

And Samuel would have John live there to run the whole thing.

Right or wrong, true or false.

Their name was here to stay.

(mellow music)

Episode 1 Preview - The Mental Smugglers

Clip: Ep1 | 30s | Hero or Traitor? It depends on which side of the pond you live. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Slatersville: America's First Mill Village is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media