Finding Your Roots

Episode 4: The Vanguard

Season 4 Episode 4 | 52m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

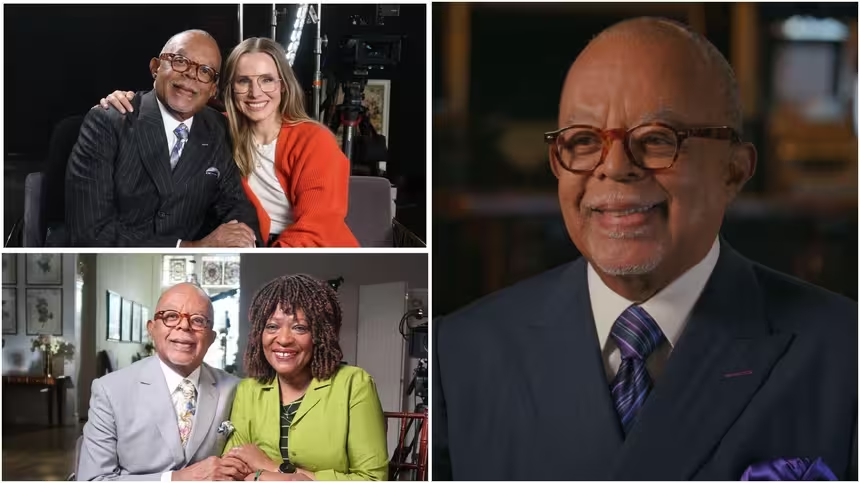

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ava DuVernay, and Janet Mock join Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Three guests who have helped to redefine Black America in the last decade find their identities challenged as they learn about their family origins.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Episode 4: The Vanguard

Season 4 Episode 4 | 52m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

Three guests who have helped to redefine Black America in the last decade find their identities challenged as they learn about their family origins.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipHenry Louis Gates Jr: I'm Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots".

In this episode, we'll meet film director Ava Duvernay, social activist Janet Mock and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Three visionaries who've changed our understanding of Black America while knowing little about the ancestors who made their own achievements possible.

Ava Duvernay: This is fascinating that your whole history is just blank.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Totally blank.

Ava Duvernay: We just don't know.

Janet Mock: I didn't think that this was possible.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I just want to know what was going on.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: To explore their roots, we've used every tool available, genealogists helped stitch together the past from the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts have utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

And we've compiled it all into a book of life.

Ava Duvernay: Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We created this just for you.

Janet Mock: Oh my God!

Henry Louis Gates Jr: A record of all our discoveries.

Ava Duvernay: It feels like ghosts on paper.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Ava Duvernay: It's kind of haunting.

Janet Mock: I'm processing, I'm, like, hyperventilating.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: It's a beautiful thing, it's a beautiful thing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: My three guests are part of a new wave of African Americans who are interpreting the Black experience in fresh and challenging ways.

Janet Mock: I stand here as someone who has written herself onto this stage.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: In this episode, they'll explore the experiences of their own ancestors, hearing stories that will change the way they see themselves.

(Theme music plays) ♪♪ (Inaudible chatter) Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ava Duvernay is a Hollywood miracle.

She's a producer, director and writer, working in scripted fiction and in documentary, and succeeding brilliantly at both.

As one of only a handful of Black woman film-makers, Ava has overcome tremendous odds and she credits it all to her family.

Ava Duvernay: Everything I do I'm trying to please them.

Make them proud.

Send them an email.

Send them a text.

Did you see this?

Just make them happy.

My mom notoriously gives the best reactions of anyone.

It's your birthday?

It's your birthday!

Congratulations!

We love to do things just to see her react.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's great.

Ava Duvernay: So I find that when I really dissect my career, everything that I'm doing is just to get my mother's reaction.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ava's big breakthrough came in 2014, with the film "Selma" which tells the heroic story of the voting rights campaign of 1965.

It's an astonishingly powerful work, capturing one of the most iconic chapters of the Civil Rights Movement in intimate human detail, a distinct approach, that reflects Ava's own history.

Ava Duvernay: The reason why I felt so connected to it, immediately, and not as intimidated by it as I guess I probably should've, in hindsight, but connected to it was because of the town of Selma, and that was where my father, the area that my father is from, Lowndes County, Alabama.

So, I'd been there, I'd spent summers there, Christmas vacations there.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And it's so unusual, you know?

People, you would think, well, I read Taylor Branch, or I saw Martin Luther King when I was a kid, or whatever, but for you it was about the community.

Ava Duvernay: It was just the people of Selma.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You made the Black people of Selma subjects, rather than objects.

Ava Duvernay: Yes, that's what we tried to do.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Selma won dozens of awards, it was nominated for two Oscars and it made Ava one of the most sought after directors in Hollywood today but even as she branches out, Ava is still driven by her connection to her African American heritage.

Ava Duvernay: It's a huge part of my identity.

I mean, that's obvious, but I mean if I was put in a room and made to choose, one side of the room was Black people and one side of the room was women, for me, race is, um, kind of takes the lead in terms of the way that I identify, so I would be over with the Black folk.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Do you think that'll change, where race trumps gender, race trumps class, race trumps everything?

Ava Duvernay: I don't.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mm-hm.

Ava Duvernay: I don't, you know?

I think that we live in times that are very much defined by race.

I think that we won't see change, um, to that in our generation, or even the generation right behind us.

And so, for me, to be African-American is very much part of my heartbeat.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I want people to be disturbed, like the literature I love disturbs me.

I want them to, you know, to feel that.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Like Ava, Ta-Nehisi Coates is re-imagining Black America through a unique lens, his best-selling memoir, "Between the World and Me" is an impassioned account of what it means to be a Black man in America today.

And it comes on the heels of a series of seminal essays about Obama's presidency, policing and the historical case for reparations for slavery.

Taken as a whole, Coates' work has marked him as one of our leading public intellectuals, so I was surprised to learn that he didn't grow up wanting to be an intellectual of any sort.

On the contrary: Ta-Nehisi found school insufferably boring.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I hated being talked at.

I still hate being talked at.

Having to sit there and listen to somebody talk to you for 50 straight minutes, and then go to another room where they do that over and over again for an entire day, I just, I had nothing for it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: In spite of his troubles in the classroom, Ta-Nehisi told me that he was irresistibly drawn to writing and that his parents never failed to encourage him, even when his prospects seemed bleak.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I've been writing for as long as I can remember, you know, in various intonations, poetry, you know, hip-hop, um, essays, fiction, I've been doing that for as long as I, my mom, when I used to get in trouble, used to make me write essays.

You know, so, yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: How long did it take to realize you could fly as a writer, that you could support yourself as a journalist?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: A long time, probably about 15 years.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Really?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah, like what I realized was not so much that I could make a stable living doing it, but it was who I was, and I couldn't change that, and so, you know, if that meant that, you know, I was, you know, gonna go down with the ship, then that was what it was.

I didn't have another ship.

That was it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Staying on "the ship" would prove to be a wise decision.

Ta-Nehisi has developed a highly distinctive voice, born of a profound connection to Black politics, culture, and history.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: When I think about Black folks, I think about struggle.

You know, I think about struggle, you know, in the face of, you know, what looks like, you know, no hope at all, you know, struggle because struggle has its own rewards.

That, that to me is the greatest inheritance, you know, the necessity, you know, to fight, you know, no matter, you know, whether, you know, you think you're gonna win or not.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Absolutely.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: The whole reason that I'm here, I'm the result of folks struggling against things much, much harder and darker.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Making a way out of no way.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Right, right.

Janet Mock: I stand here, to unapologetically proclaim that I am a trans woman, writer, activist, revolutionary, of color.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: My third guest is Janet Mock, one of America's leading advocates for transgender rights.

Like Ava and Ta-Nehisi, Janet knows what it means to struggle, she's been doing it almost her entire life.

Janet Mock: I think one of the first things we learn about ourselves is our gender, and so, for me, right when that doctor, I assume, smacked me on my ass, and he said, "This is a boy," that's kind of what everyone went along with, because of the presence of what my body looked like.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Janet was born in Honolulu, the child of an African American father and a Hawaiian mother.

She realized at a very young age that she was a girl.

But getting others to accept that fact was another matter.

Fortunately, she always had her mother's support.

Janet Mock: You know, when I came to my mom and I told her, I didn't know what language I used, but when I basically told her that I was trans at 13 years old, she didn't raise an eyebrow, she didn't tell me that I need to get my hair cut, she didn't, you know, say, she didn't negate me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's extraordinary.

Janet Mock: And you know, my mom too, her, a lot of her family, you know, they doubted her parenting.

They're just like, "Why are you letting him wear these clothes?

Why are you letting him take hormones?

Why are you letting him gallivant around the playground?"

Henry Louis Gates Jr: "He needs to go to military school."

Janet Mock: Or something, right, in the sense, you know, like, and my mom, she took on a lot of that stuff, but she never brought that to me.

So, I didn't grow up with a sense of, um, I need to change, or I need to fit, or I need to shrink myself or hide parts of myself.

And I think that that deeply impacted my life and enabled me to do all of the work that I do now.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Janet's mother gave her the confidence she needed to succeed, but Janet knows that she's an exception.

And because of that, she's deeply committed to those who haven't been so fortunate.

Janet Mock: I think what I always feel is the burden to represent.

I know that it is so rare for girls who grew up like I did and who are growing up like I did to have access to the things that I've been given.

And so, as a Black trans woman, I may be the only when I enter these spaces, but the goal is to ensure that when I leave, you know, other people can come in.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: All three of my three guests identify strongly with their African American heritage.

Each sees their life and their life's work, in the context of something much larger: the long unfolding history of Black America.

Now, we're going to see how their own ancestors' experiences fit into that history, or in some cases, how their stories challenge it.

Are you worried about this?

Ava Duvernay: I'm very worried about this.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We started with Ava Duvernay.

Ava was raised by her mother and step-father, a man named Murray Maye.

Murray grew up in Lowndes County Alabama, a focal point of the struggle for voting rights in the 1960s.

Ava told me that he had a significant influence on her film "Selma."

Ava Duvernay: I scouted that movie with him.

We went out and we scouted the movie together, and he would talk to me about the legacy of the place.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Do you think that "Selma" was a love letter for Murray Maye?

Ava Duvernay: Oh, for sure, for sure.

Yeah, I made it for him.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Murray passed away suddenly in 2016.

Ava is still struggling with his loss.

In fact, one of the reasons she wanted to be in our series was to honor his memory.

Ava Duvernay: My daddy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Have you seen that picture before?

Ava Duvernay: No.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's Murray Maye in 1971.

Ava Duvernay: Where did you get this picture?

Wow, my favorite guy in the whole world.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What influence did he have on you, when you were growing up?

Ava Duvernay: Big, just a very kind, quiet person.

You know, just incredibly, loving, loving person, so, he taught me, he was an entrepreneur.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Uh-huh.

Ava Duvernay: So, he had a small carpet and flooring business, and so he taught me a lot about independence, you know, getting up in the morning and going to work, you know, even when it's dark outside.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Uh-huh.

Ava Duvernay: And when I look back and try to trace where I got my independent spirit from and my entrepreneurial spirit, you know, not being satisfied working for people, not just being satisfied making films, wanting to distribute films, wanting to produce my own films, wanting to finance my own films, that really comes from my pops, Murray Maye.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Hmm, well, it was an effective lesson.

I mean he was a great teacher, because look at you.

Ava Duvernay: He was, yeah, he was, the best.

(Crying).

The best.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ava wanted to learn all she could about Murray's family, but we quickly hit a wall: slavery.

Slaves were rarely recorded by name in official government documents, so to trace an African American family back into the slave period, you need to find them listed among the papers of their owners.

This can be extraordinarily difficult and on almost every branch of Murray's family tree, it proved impossible.

There was just one exception.

You're looking at the 1880 census of Hickory Hill, in Alabama.

Ava Duvernay: "Pinkney Bruner, 46, Margaret Bruner, 45, and Frances Bruner, 13."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's Murray's great-grandmother, Frances Bruner.

She's living with her parents, Pinkney and Margaret Bruner and you've never heard of them?

Ava Duvernay: No.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Pinkney Bruner was Murray's great-great-grandfather.

He was born around 1835, in the heart of the slave era.

And when we tried to identify his owner, we got lucky, the 1850 census contains a "slave schedule" for two men, possibly brothers, named John and Charles Bruner, who lived in Lowndes County, Alabama.

Though there are no names of the enslaved people listed on the schedule, it does describe the Bruner slaves by age, gender, and color.

Ava Duvernay: "14, M, B."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That indicates that the Bruners owned a 14-year-old slave who was male and Black, and we know that Pinkney would've been about 15 years old in 1850, so that may be Pinkney.

Ava Duvernay: Lowndes County, Lowndes slave inhabitants, same last name, age, male.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Male, and one year difference, so.

Ava Duvernay: Yes, it's probably him.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it like to see that?

Ava Duvernay: It feels like ghosts on paper.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Ava Duvernay: A kind of haunting.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We can't be certain that this is Murray's ancestor.

But we uncovered something that made it seem very likely, a labor contract that Pinkney Bruner signed with John Bruner just months after the Civil War ended.

Contracts like these were common in the early days of reconstruction, when many newly-freed African Americans went to work for White farmers, often the same farmers who had owned them before the Civil War.

So this is further evidence that Pinkney was probably owned by the Bruner family.

More importantly: it shows us the challenges that Pinkney faced after emancipation.

Because, unsurprisingly, the terms of this contract were not favorable to him... Ava Duvernay: "To wit, I agree to clothe, feed, furnish house-room free, also to let them have their patches of corn and rice that they have in cultivation for their services for the present year."

So this is a document saying that what I will give you for continuing to work so that I can profit is I will clothe you, feed you, give you a place to stay, and you can eat, you can have the corn and the rice.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Uh-huh.

Ava Duvernay: No money in hand, no wealth building, you will not own anything, just continuing what you were doing before.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What was a slave going to do?

A slave had no money.

Ava Duvernay: No options.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Just got a legal name.

Ava Duvernay: Where you gonna go?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Where you gonna go?

Ava Duvernay: What you gonna do?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Pinkney Bruner would spend the rest of his life farming in Lowndes County.

But that isn't all that he did, in 1867, Pinkney became a registered voter, likely the first person in his family to do so.

Ava Duvernay: Wow, that's incredible.

That's great, that's a big deal.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What do you think the act of voting meant to Pinkney?

Ava Duvernay: I just, it's such a big deal because I've studied it so much for both Selma and 13th, and Selma basically, just the odds that my father is from the place, this is the birth, this is the epicenter of that fight.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, yeah.

Ava Duvernay: And for my own family to have participated in it, in this way, so deeply.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What do you think this would have meant to Murray, to see this?

Ava Duvernay: Oh my gosh.

He would just be, this is his thing, proud, fascinated, you know, obsessed with it, which I now am.

Yeah, I know my dad.

Yeah, this would've meant a lot.

I know it does mean a lot.

Yeah, wow.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I did not die in my aimless youth, I did not perish in the agony of not knowing, I was not jailed.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Like Ava, Ta-Nehisi Coates was deeply influenced by the man who raised him, his father, Paul Coates, was an ardent Black nationalist and the shaping force in his son's intellectual development, though growing up, Ta-Nehisi was not always sure that he wanted to be shaped.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I was the sixth child, but I was the first one that he had who could be raised according to his codes, things that he wanted done, you know what I mean, to make a child as, he, I think, put it at the time, "Conscious."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, you were an experiment.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I was, I was, it's so weird.

And I think about that all the time you know what I mean, because there were things that I like about it, things I don't like about it.

You know, we didn't celebrate Christmas.

We fasted on Thanksgiving.

Uh, we didn't celebrate any holidays except birthdays, Halloween, none of that.

We didn't do any of that.

We didn't even celebrate Kwanza, there wasn't no fake.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You didn't celebrate Kwanza?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: No, there was no fake Christmas.

No, it was, there wasn't none of that.

There wasn't none of that.

There was work.

There was a lot of work in that house.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So tell me, how are you most like your father?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I think his skepticism of the world.

I think that's probably the biggest thing that I got from him.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Paul's skepticism was hard-earned.

Born in 1946, in a nearly-all-Black neighborhood in Philadelphia, Paul grew up in poverty, as a young man, he joined the army and was sent to Vietnam and served in an almost all-White unit.

That experience transformed him, heightening his awareness of the problems with race relations back home in the United States.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: He considered himself to be an American when he went.

I think that one of the things that happens is, um, you go off to war, and you know, you are faced with the fact of giving your life for your country, and it puts in sharp relief, you know, what your country would do for you.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Paul returned from Vietnam, moved to Baltimore and soon joined the Black Panther Party.

♪ Group: The revolution has come.

♪ ♪ Time to pick up the gun.

♪ Henry Louis Gates Jr: The Panthers were advocating radical ways to address America's racial problems, including armed resistance.

Man: We must arm ourselves, we have to put a shotgun at every door across this racist nation.

Every Black man has got to get yourselves armed so we can have the power in our hands.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Paul would spend two years with the Panthers, ultimately serving as a defense captain and Ta-Nehisi grew up hearing stories about his father's activist days, but he'd never seen the evidence of just how radical his father was... We found it, in the files of the FBI!

Ta-Nehisi Coates: It's hilarious, I shouldn't be laughing, I'm sorry, dad, I shouldn't be laughing, it's not funny.

Look at that afro, whew.

Uncombed, unkempt, whew.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: There are very few times I've been able to show a guest their father's mug shot.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Right, right, right, right, right, wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: On April 30, 1970, the Baltimore Police apprehended Paul and three other Black Panthers, as they were removing guns from a stash house, this was one of at least five times that Paul was arrested during his years with the Panthers.

And he didn't always surrender peacefully... Ta-Nehisi Coates: "William P. Coates pointed a rifle, a 7mm fully loaded at us.

Coates was commanded three times to lower the weapon, and only after Detective Sergeant Livingston leveled a shotgun did Coates comply..." Henry Louis Gates Jr: Can I ask you what it's like to read that?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: It weirdly accords with what I know of my dad.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Really?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I'm not reading this like I'm shocked.

Yeah, I mean, somebody said, "Your dad did this."

I'd say, "That seems legit."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Thank God he lowered that shotgun.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah, seriously, we wouldn't be here talking.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, wouldn't be here at all.

After leaving the Panthers, Paul worked in the library at Howard University and filled the family home with books about Black history, helping inspire Ta-Nehisi to become a writer.

But when it came to his own family's history, Paul passed down very little information.

Leaving his son with some very fundamental questions about his roots.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Well, I always thought it was, like, weird that my father's family was from Philadelphia.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Sure.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I mean, obviously there's a free Black population that was there, but I long suspected that, you know, they had gotten there from somewhere else, you know, and you know, always wanted to know where else.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The answer to Ta-Nehisi's question lay in the 1910 census, where we found an entry for his great-grandparents, George and Mora Cryor, listing their place of birth... Ta-Nehisi, take a look at that map.

You see those dots?

Every branch of your father's tree stretches into Virginia, not just the Cryors, but every other line we can identify and most of them go just to those two counties, Sussex County and Prince George County.

Have you been to those places?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Never.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You think of yourself as a city boy.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Basically, yeah, that's what I was.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Well, you are a deep country boy.

Before your family moved to the city.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Evidently so, evidently so.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ta-Nehisi's roots lie in what was once a center of American slavery, less than forty miles from Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, a place where African American families were held for generations in bondage.

Indeed, Prince George County, held more slaves than free people in the decades leading up to the Civil War.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: So, the majority of people are enslaved in that county?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, there were roughly 5,000 slaves and a total population of about 8,000.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Whew, that's so disgusting.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah, that is, that, you know, I know I should be more forgiving, but I mean, you know, you live in a county where the majority of people there are living in chains.

That is incredible to me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Despite the overwhelming numbers, and the dearth of records, we were able to identify a number of Ta-Nehisi's enslaved ancestors by name.

Among the oldest was his fourth great-grandmother, Lavinia Cryor.

Lavinia was born in Virginia around 1810 and died sometime after 1870.

Which means that she actually witnessed America's transition from slavery to freedom.

I know you've thought about slavery, but have you thought about the lives of your ancestors who were slaves, people from whom you inherited DNA.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: No, no, I mean, I've thought about it, an ancestor, in the most broadest sense of the word.

You know, um, I couldn't even place it geographically, you know?

Um, so no, I really didn't have the capacity to think about it, you know, in terms of flesh and blood.

I mean, I knew who I was and I knew what I was, and I knew that I probably wasn't, you know, my father's people were probably not, you know, recent immigrants.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right, right.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah, so, um.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You didn't come through Ellis Island.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I knew that, I knew that, yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it like to learn this?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: That's significant.

To be somebody born in 1810, and to see that end, uh, you know, enslavement, I mean, that is, whew.

That's incredible.

So, you're born in 1810, you're born into a young country.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, yeah.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I mean, with a really, I mean, you're born almost into an idea, whew.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mm, yeah, absolutely.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I mean, so Thomas Jefferson is still alive, uh, I think.

I think I'm getting that right, 18... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, yeah.

He didn't die till 1826.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: That's right, that's right.

So, you know, like, within founder's time.

I mean, that's something.

That's something, wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Like Ava and Ta-Nehisi, Janet Mock grew up knowing little about her African American roots.

Her parents split up when she was just four years old, and for several years, she was raised by her Hawaiian mother.

When she finally began living with her father again, their relationship was strained because of his unwillingness to accept her identity.

Janet Mock: My father would probably say that I was his greatest challenge.

He began giving me a lot of speeches about how I should act, what boys do in the world, what girls do, and how I should not do that.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, well, that obviously worked.

Janet Mock: Yeah, that worked really, really well, so I think that I was my father's greatest challenge, because he epically failed, in that, in that, um, in that arena.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Janet and her father have reconciled but even so, she still has many questions about his roots.

She knew his parents, but not his grandparents.

And she has no knowledge at all of his deeper ancestry.

We traced it back to her great-great-grandfather, a man named Harold Mock, born in Louisiana in the early 1880s.

His father, Janet's third great-grandfather, was named "Henry Mock."

Henry was born around 1847.

Have you ever heard of any of these people?

Janet Mock: No, this is already a lot.

More than I knew when I came in.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I mean, it's over 150 years, a century and a half of roots.

What's it like to see this all laid out?

Janet Mock: That Mock was a consistent name.

I always was curious, because it is my last name of course, which I inherited from my, my father.

You know, people have always asked me, a lot of Chinese people have that last name, so they're like, "Is there, you know," and I was like, "I don't think that there's anything," so, you know, how Black folk chose or grabbed names, I didn't know what the root or region was.

So, to see that it went all the way up in this way.

I didn't think this was possible.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Listen to this, your third-great-grandfather, Henry Mock, was born around 1847, which means he was likely born into slavery.

Janet Mock: I knew that that was coming, but now I'm processing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, right.

To learn more about Henry, we began to search records in Franklin Parish, Mock, where he died.

We discovered that he sometimes went by the name "Hal" and that he may have been born in Alabama or Georgia and then we found something even more significant.

Janet, this is a page attached to the 1860 census for Franklin Parish, Louisiana.

It's called a slave schedule.

Janet Mock: "Name of slave owner: William T. Mock.

Description of slave: age 14, sex: male.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It means that a man named William T. Mock owned a 14-year-old boy in 1860.

So, that boy would have been born around 1846, which is around when your third-great-grandfather was born.

Janet Mock: It looks like he had five slaves.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, our genealogist believed that you are looking at the registry of your ancestor, who was a piece of property with no name, along with, as you say, five other human beings who were enslaved by William T. Mock.

Janet Mock: Well, that's interesting to see where "Mock" came from, and then my attachment to that last name, that it goes all the way through me and my brother, and my brother who now has a child, and that we know that it goes back to a White man named William.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it like to see this?

'Cause there are a lot of people who sit where you sit, and I can't do this.

We can't give them this information.

Janet Mock: Well, there's a reconciliation for me personally.

You know, I chose my first name.

I chose Janet, um, and to see that then, you know, my, my, um, great-great-great-grandfather chose Mock.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

Janet Mock: He could have changed it to something else if he wanted to.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's right.

Janet Mock: He chose that name.

And so, for me, there is a reconciliation between those parts of myself, um, the identity that is mine and the identity that is my family's.

Um, and so, there's a peace there that comes from that.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, yeah, we had already learned how the ancestors of Ava Duvernay's step-father endured generations of slavery in Alabama.

Now we turned to Ava's biological father and uncovered a very different kind of story, a story about people who never endured slavery, at all.

It began in New Orleans, where we were able to trace Ava back to her fourth great-grandparents: Henry and Magadeline Glaudin, they were born free in the late 1700s.

What's more, we discovered that Henry was born in a most surprising place.

Ava Duvernay: Saint Domingue.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You ever hear of that island?

Ava Duvernay: No.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It became the Republic of Haiti.

Ava Duvernay: Oh, wow, is that right, wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Did you have any idea, in your wildest imagination?

Ava Duvernay: No, I had no idea.

It's just fascinating that your whole history is just blank.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Totally blank.

Ava Duvernay: You just don't, we just don't know.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I couldn't wait to get you in this chair, because for a Black person, your roots, as descended from free people, are extraordinarily deep.

Ava Duvernay: Rare.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Extraordinarily deep.

Ava Duvernay: How did they come to be free in Haiti?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's what the Lord sent me here to tell you.

Ava Duvernay: Okay, I'm glad you have the answers.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The answers lay in the archives of St.

Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, which contain the baptismal records of several of Henry and Magadeline's children.

As we combed through these records, we noticed something unusual about Ava's fourth great grandparents.

Your fourth great-grandmother, Magadeline, is listed as a free mulatta, but there's no color indicated for your fourth great-grandfather, Henry.

Do you know what that means?

Ava Duvernay: He's White.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Very good, Henry was a White man.

Ava Duvernay: Okay, okay.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: There, there you go.

Ava Duvernay: Got you.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's right, the queen of Black documentary film.

Ava Duvernay: You knew it was going to be in there somewhere.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Ava Duvernay: I knew it was coming.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Most of us know it's there somewhere, but we know where, in your case, and who.

Ava Duvernay: Yeah, yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ava's fourth great-grandfather, Henry Glaudin, was born on the island of Saint Domingue in November of 1779.

At that time, the island was a French colony and it was a center of slavery in the new world.

And evidence shows that Henry's father, a Frenchman, also named Henry, played a role in the slave economy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You're looking at an ad that was published on May 30, 1780, in a Saint Domingue newspaper.

Can you read the translation?

Ava Duvernay: "A Negro Congo, named Toni, stamped P.Binet and above it H.Glaudin, fisherman by trade, ran away three weeks ago.

Those who recognize him are requested to arrest him..." Henry Louis Gates Jr: Now, that ad was placed by Henry Glaudin Sr.

Ava, your fifth great-grandfather was a slave owner.

Ava Duvernay: Got it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Read the first line again, a Negro Congo... Ava Duvernay: "Named Toni, stamped P.Binet and above it H.Glaudin."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right, stamped.

Ava Duvernay: Yeah, uh-huh, uh-huh.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Stamped, this tells us that Henry branded his name on his slave.

Ava Duvernay: Mm, mm, vicious.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And this isn't the only ad for a runaway slave that was placed by your ancestor.

We found three others.

So, as far as we know, Henry owned at least four slaves, and possibly more.

Ava Duvernay: Mm, mm and branded them.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And then his son made the decision to have a child with a Black woman.

Ava Duvernay: Yeah, fascinating.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ava wondered how her family got from Haiti to New Orleans, the story is so amazing that it could be her next movie!

In August of 1791, enslaved Black people on Saint Domingue's rose up against their masters, launching what we now call the Haitian Revolution, the largest and bloodiest slave revolt ever staged in the Americas and the most successful slave revolt in the history of the world.

Fighting would last for more than a decade but by 1803, the outcome was clear, as a formidable Black army, led by their brilliant general named Jean-Jacques Dessalines, marched across the country, exterminating the remaining French.

As they neared the Port of Jeremie, where Ava's ancestors were living, her fourth great-grandfather, Henry Glaudin, made a desperate decision, he and his family, fled by boat to Cuba... Ava Duvernay: "The city of Jeremie finds itself on the verge of being attacked and sacked by the rebel Blacks.

My passengers appeal to your righteousness so that you might act to allow me to sail up to the port.

Henry Glaudin."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That is a petition for asylum, actually written, by your fourth great-grandfather.

And he wrote that to the governor of Cuba.

So, when the rebels advanced on Jeremie, your ancestor split.

Ava Duvernay: Ah, right.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And he fled to Cuba.

Ava Duvernay: Good call.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, are you relieved to find this out, that your ancestors were spared this siege, right?

Ava Duvernay: Well, it's so interesting, you say your family, your family, aren't you happy to know your family is safe, and but for me, I'm listening to this story from the side of the people... Henry Louis Gates Jr: I know.

Ava Duvernay: You know what I mean?

I'm like then what happened, and you're saying the family, from the people that they're revolting against, so that, emotionally, is a disconnect for me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I know, it is.

But if Dessalines had gotten there first, poof, this would be like a science fiction movie.

Ava Duvernay: It's true, I'd just disappear.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You'd disappear, yeah.

You wouldn't be here.

Ava Duvernay: See, I thought I was going to have some revolting ancestors in Haiti.

I was going to be like yes!

But alas, the other way around.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The Glaudins were among roughly 20,000 French subjects who fled to Cuba during the Haitian Revolution.

But events back in Europe would soon bring an end to their sanctuary.

In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain, installing his brother on the throne.

In an act of defiance, the Spanish colonial government in Cuba expelled nearly all of the island's French refugees.

So the Glaudins were forced to flee once again, this time to New Orleans, completing a journey that violates Ava's most fundamental ideas about her own roots.

Ava Duvernay: I mean I guess I just assumed there would be slavery in the line in the traditional way that I've come to learn it and know it which is based here, in the States, you know?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

Ava Duvernay: But they arrived to the States so late in that line, and he wasn't even Black.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

Ava Duvernay: So, I don't even know what I'm... My mind is reeling and trying to figure out how, how we became, how this happened.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yours is not the typical up from slavery, this is not when we were picking cotton.

Ava Duvernay: That's what I thought, though.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It wasn't happening.

Ava Duvernay: I mean but isn't it so odd that part of, I mean, you know, not that it's been romanticized, but that, that there is this kind of singularity of narrative around African Americans in slavery, that there is this kind of shared, you were brought here from the continent on slave ships, and you landed somewhere, probably in the South, and there was this, you know, this long line of but slavery, a, touched many different parts of the world, beyond the United States.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Slavery's as old as civilization.

Ava Duvernay: Yeah, and, um, you know that there were other ways to get to this place.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And there is not one standard narrative.

Ava Duvernay: It's not one standard narrative, but that's become the narrative.

The truth of us is complicated.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It's very complicated.

Ava Duvernay: All of us, yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Turning back to Ta-Nehisi Coates, we uncovered another family story that challenges the "standard narrative" of the African American experience.

It begins in the archives of Worcester County, Maryland, with the estate inventory of a man named Henry Jones.

Jones was a farmer and this inventory, compiled after his death, lists the values for all the property he owned, including Ta-Nehisi's third great-grandmother... Ta-Nehisi Coates: "Negro girl Harriet, $250" hmm, that's something.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That is your third-great-grandmother, someone else's property.

Her value, worth $250, in 2015 dollars, it's 8,000 bucks.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah, it's heavy, it's heavy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Almost every African American grapples with the fact that some of their ancestors were enslaved.

And those ancestors can only be glimpsed through the records of their owners.

But in Harriet's case, the records also contained quite a surprise.

Her owner, Henry Jones, died in 1849.

And his will gave Harriet two things that few slaves ever received: freedom and land.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: "It is my will and desire that my slave Harriet shall be free at the age of 28 years.

I give to my slave Harriet five acres of land at the south end of Laws Third Edition."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: This is not your typical African-American story, not your typical slave experience.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Okay, yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You have written so eloquently about slavery and reparations, but you are one of the handful of African-Americans who descend not unilaterally from enslaved people, but from free Negroes on your mom's side.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Mmm-hmm, do I get a badge, do I get some cookies, or?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No, you can't write about reparations anymore.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Right, right, right.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You one of them free Negroes, highfalutin', talented tenth.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I guess, I guess.

I'll take it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We don't know why Harriet was given her freedom.

But we do know she made the most of it.

By 1860, Harriet had married a free man of color named Lambert Smack, he's Ta-Nehisi's third great-grandfather.

And records show that he and Harriet were a remarkably successful pair.

In February of 1865, Lambert purchased two tracts of land for $900.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: That's a lot of money.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And a lot of land.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's astonishing, for a Black family?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah, no.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Especially when the average wealth accumulation for Black people is zero.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Was zero, was zero, yeah.

Yep, mmm, that's something.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: To put this story in context, we turned to the 1870 census for Worcester County, Maryland, it showed just how unusual Ta-Nehisi's family was... So, look at that.

Your ancestors' real estate was valued at $3,000 in 1870, look at the value of the real estate in all the rest of those columns.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Right.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: None of Lambert and Harriet's neighbors had any real estate.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Jesus Christ.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Five years after the end of the Civil War.

They weren't just landowners, they were wealthy landowners.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Whew.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: They were the richest people on the block, so to speak.

Think about the complexity the Black experience now, not only in the abstract in general, but in your own family tree.

You have two different Black narratives unfolding in your genealogy.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Right.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: On one side of your family, you came from people who worked the land, the slaves.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Right.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: On the other side of your family, came from people who owned the property.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Yeah, it's fascinating.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Lambert and Harriet's wealth would benefit their descendants for generations, indeed, Ta-Nehisi's relatives have owned land in virtually the same place in Maryland for almost 150 years!

Growing up, Ta-Nehisi visited cousins here and he still visits today.

It's a story of extraordinary stability.

And it confirms Ta-Nehisi's intuitions about his mother's family... Ta-Nehisi Coates: You know what's odd, my folks down on the Eastern Shore always, they always had things.

Uh, they weren't rich.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, sure.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: But they, they had things.

Do you know what I mean?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I understand.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Again, it did not look opulent.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: But it looked like y'all had done, looked like y'all had trouble putting this together.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yes.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: You know we're talking about 1865 right here?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: I started going to the Eastern Shore, well, I'm born in 1975, and it is obvious that, you know, I mean, you talking about 100 years later, and it's obvious to me these people have, again, not rich, but have things.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yes, absolutely.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Have things.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Absolutely, did your mom ever talk about that?

I mean, did your mom ever do a thing like my mom, "You come from people, we're different Negros.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: You know, my mom used to say, my mom grew up in the projects, and what she'd say, "Yeah, we grew up poor, but..." It was poor in the sense of lack of money, but my grandmother sent all three of her daughters to college.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, that's right.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: My grandmother, you know, worked, you know, basically worked herself through nursing school, but she was able to send her children away to the Eastern Shore.

You know, it was a place to go?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right, a real home.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: A real home.

A real, a very real ancestral home, and so I draw a direct line from that, you know, to the stability that my mom really provided in my life and the importance of education, and you know, the learning to read early, the writing, all of that, you know?

Maybe that's too far, but I, I do see it.

I do see it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We had already taken Janet Mock's African American family back four generations in Mock, now it was time explore a different side of her heritage, in Hawaii.

Janet spent most of her childhood in Honolulu, much of it in the care of her maternal grandmother Pearl, a native Hawaiian.

Janet Mock: We all, all, me and my cousins, were dropped off at Grandma Pearl's.

And so, she was this constant presence in my life, and I remember her making me you know, my favorite, which was hot chocolate and buttered toast.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, wow, that's good.

Janet Mock: Very simple, but you know, that's what I loved, and she'd make that for me, and she'd be playing Hawaiian music, and so, those are things that I remember.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Although Pearl was a central figure in Janet's life, she rarely spoke about her ancestry and Janet told me that her Hawaiian family is largely a mystery to her.

Janet Mock: I don't know much.

I just know that my grandmother Pearl grew up on the windward side of the island, and she was the youngest, I think, I think of, like, 12 or 13.

All of my grandparents are passed on both sides of my family, so I wasn't able to sit and have those adult conversations with them.

I feel like there's a, a lost link.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: To restore this link, we turned to the records.

In the 1930 census, we found Pearl's parents, David and Winnie Kahanaoi living in Honolulu.

Janet quickly noticed something interesting about them.

Janet Mock: "David Kahanaoi, 36 years old.

Race: Ha," which must mean Hawaiian.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mmm-hmm.

Janet Mock: "Speaks English: yes.

Winnie Kahanaoi, 37 years old.

Race: Ha.

Speaks English: no."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No, so what language do you think Winnie spoke?

Janet Mock: Hawaiian, I would, I would assume, that at that time, she must have just grew up speaking Hawaiian.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: A great deal of history lies behind this distinction, in 1893, Hawaii's last queen was overthrown, in a coup backed by American business interests, ending centuries of native rule and paving the way for the islands to become part of the United States.

During this process, the Hawaiian language was suppressed.

Indeed, when this census was taken in 1930, the language had not been taught in Hawaiian schools for more than three decades.

Today, Hawaiian is experiencing a revival and seeing that her ancestor spoke it was deeply moving to Janet.

Janet Mock: That's something that, you know, my generation mostly fought very hard for, to ensure that the Hawaiian immersion schools, where young people were able to go to smaller charter schools that were run by native Hawaiians.

You know, they learned dance.

They learned, um, the language.

They learned our history, our monarchy it kind of skipped two generations, and then it, you know, then you had to fight for it to come back and to be revived.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

Janet Mock: The fact that she could say "No, I didn't speak English."

That she didn't have to rely on that language, and she had her own language.

It makes me so happy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We were able to take Winnie's family back two generations to Janet's third great-grandparents, who were likely born in Hawaii in the 1850s.

And when we turned to Winnie's husband David, we found something I didn't expect.

Have you ever seen those photos before?

Janet Mock: No.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Well, you're looking at David's parents, Abraham and Theresa Kahanaoi.

Janet Mock: Oh my God.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, what's it like to see your great-great-grandparents?

Janet Mock: Nice to meet you?

I guess.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Those are your people, your family.

Your blood.

Janet Mock: I'm surprised that the parents of, you know, my great-grandparents are, are here and counted.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I am too and I'm delighted.

Janet Mock: This is very exciting for me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Janet wanted to know more about Abraham and Theresa.

There were few records to guide us, but by combing through the city archives of Honolulu, we were able to glimpse details of their daily lives... Henry Louis Gates Jr: This is a directory for the city and county of Honolulu from the year 1913.

Janet Mock: Wow, "Kahanaoi, Abraham, laborer, Kaneohe, Heeia."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: In 1913, when he was around 46 years old, Abraham was a field worker in Heeia, which is a farming region.

Janet Mock: Mhmm.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: On your left is another entry from another city directory, but this one is from the year 1921.

Janet Mock: "Kahanaoi, Abraham, taro planter."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Taro planter.

So, eight years later, when your great-great-grandfather was around 54, he's planting taro and while we can't be sure of what he was doing as a young man, it seems likely that your great-great-grandfather spent his entire life working in the fields.

Janet Mock: Yeah, I guess that it just, it affirms, um, assumptions that I had about, you know, my family.

You know, my grandmother was, was hard-working, self-sacrificing, um, a strong woman, just physically strong and capable, you know?

And so, this is like a missing puzzle piece.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Janet Mock: And so, then I want to pull these pieces together, and that these pieces make me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's a beautiful way to put it.

The paper trail had now run out for each of my guests.

It was time to see what DNA could tell us about their deeper roots.

For Janet, whose admixture reveals her African, Hawaiian, and European heritage, this was an occasion to expand her sense of her own identity.

Janet Mock: You know, I say that I am a Black trans woman, but I think that I need to complicate that even more, um, to ensure that I am, you know, as exacting and saying that I'm a native Hawaiian, Black, trans woman.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, I mean, look, these are your roots.

Janet Mock: It leaves me with homework.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh yeah.

Janet Mock: Thanks, professor.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: For Ava and Ta-Nehisi, DNA raised a more pressing question, they wanted to know just how African they really are.

Okay, there you go, want to read them out loud?

Ta-Nehisi Coates: 83.4% Sub-Saharan African, 15.6% European.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, you ought to give 15.6% of your salary back.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I want you to take a guess.

You've got a lot of White people in that family.

Ava Duvernay: I know.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Okay, just take a wild guess.

Ava Duvernay: More than 50%.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: European?

Ava Duvernay: Yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Okay, let's see, please... Ava Duvernay: I wouldn't have said that before, but... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Let's see if you're right.

Please turn the page.

Can you read the percent?

Ava Duvernay: I'm Black.

I am Black.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Welcome back, welcome back, welcome back, you're blasted off to St.

Domingue... Ava Duvernay: You're funny!

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Santiago de Cuba.

Can you read those percentages?

Ava Duvernay: 57.3% African, thank you, 41.5% European.

This makes me so happy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I can tell.

Ava Duvernay: This just makes me so happy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Wait, but what difference does it make?

Ava Duvernay: I had had a whole narrative in my head of like it doesn't matter, it's how I identify, it's how I'm seen in the world, it's how I, you know?

I did the whole thing, but I totally just felt like my heart just burst open, because it does make a difference to me.

What a great thing.

This was an incredible, incredible experience.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's the end of our journey into the family stories of Ava Duvernay, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Janet Mock.

Join me next time as we meet new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots".

Narrator: Next time on "Finding Your Roots".

Three big-screen celebrities; descendants of recent immigrants.

Paul Rudd.

Paul Rudd: Wow, yeah, this is amazing.

Narrator: Scarlett Johansson.

Scarlett Johansson: Well, my dad used to tell me that I was a Viking princess.

Narrator: And John Turturro.

John Turturro: Wow!

And with my family, nothing surprises me.

Narrator: Ancestors who risked it all on America.

Paul Rudd: We can learn everything form history.

Narrator: "Finding Your Roots".

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: