Finding Your Roots

Episode 6: Black Like Me

Season 4 Episode 6 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

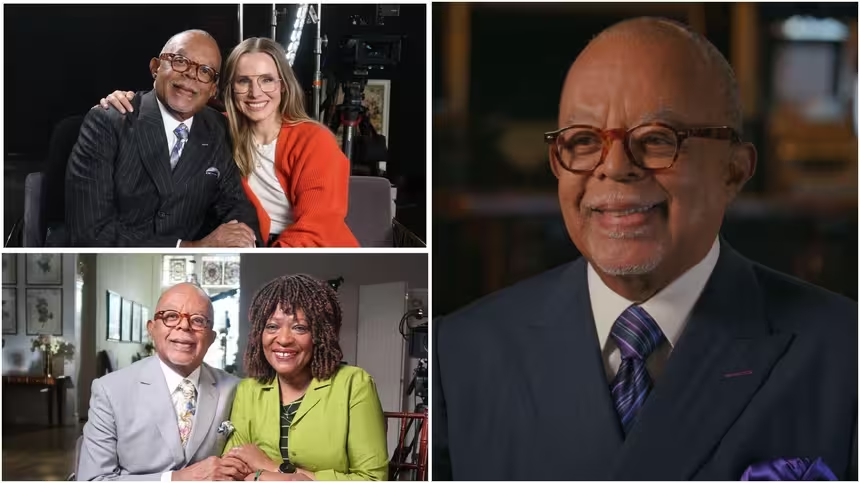

Bryant Gumbel, Tonya Lewis-Lee and Suzanne Malveaux join Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Three African-American guests delve deep into their family trees, discovering unexpected stories that challenge our assumptions about black history.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Episode 6: Black Like Me

Season 4 Episode 6 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Three African-American guests delve deep into their family trees, discovering unexpected stories that challenge our assumptions about black history.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipHenry Louis Gates Jr: I'm Henry Louis Gates Jr, welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll meet journalists Bryant Gumbel and Suzanne Malveaux and television producer Tonya Lewis Lee.

Three African Americans whose family trees challenge our most basic assumptions about Black history.

Is it possible to love someone who owns you?

Is it possible for you to have a normal, loving relationship with someone you own?

Suzanne Malveaux: I can't imagine that's possible.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: But it looks like they did.

Bryant Gumbel: "Martin Lamotte, Confederate."

Wait, wait, wait.

He's a Confederate soldier?

He's a rebel?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Did you know that any Black men served the Confederacy?

Bryant Gumbel: No, unh-uh, unh-uh, unh-uh.

Tonya Lewis Lee: It's like this experience isn't really acknowledged; it's like it doesn't exist.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No, and it's a real part of the Black experience.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Right.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It's just as Black as slavery.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Exactly.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists helped stitch together the past from the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

Bryant Gumbel's book of life.

And we've compiled everything into a book of life... Suzanne Malveaux: Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: A record of all of our discoveries... Tonya Lewis Lee: That's astounding, really astounding.

I, it's amazing to me.

Bryant Gumbel: I'll be damned.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What do you think of that, isn't that a surprise?

Bryant Gumbel: It shows you how stupid people are about race.

They are.

Suzanne Malveaux: Oh, my gosh, it's hard to breathe.

I'm having a hard time breathing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Tonya, Bryant, and Suzanne came to me hoping to explore the experiences of their ancestors in slavery, and in freedom.

They're about to see that their ancestor's lives were far more complicated than they'd ever imagined.

(Theme music plays) ♪♪ ♪♪ Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant Gumbel is a broadcasting legend.

Bryant Gumbel: Good morning, I'm Bryant Gumbel along with Jane Pauley, these are the headlines this Friday morning.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: In 1982, he was hired as co-host of the "Today Show," becoming the first African American to anchor a national morning talk show.

He's been a fixture on television ever since, meeting presidents, popes, and pop stars.

From a distance, Bryant might seem like a man who's transcended the limits of race in America but talk to him for a moment, and you'll realize that that's not how he feels.

Bryant Gumbel: I think people assume because you are a known person and because you have some degree of money that the problems of color are not visited upon you, and nothing could be farther from the truth.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant was born in New Orleans in 1948.

When he was a child, his family moved to Chicago to escape the Jim Crow South.

But the North didn't turn out to be a racial paradise.

And neither did his profession.

Bryant Gumbel: We had people who said they were gonna refuse to go on the air with me, because they didn't want a person who looked like this sitting next to a lady who looked like that.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, right.

Bryant Gumbel: Oh, yeah.

Not, you well remember... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Bryant Gumbel: Um, was considered not very popular at that time.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: While some targeted his network for hiring a Black man, paradoxically others targeted Bryant for not being "Black" enough and supposedly talking like a "White man."

But through it all, Bryant persevered and ultimately thrived because under his warmth lies a steely resolve.

A quality he says that he inherited from his father, a no-nonsense judge.

Bryant Gumbel: I have at times been attacked, "attacked" is a strong word, um belittled, whatever, for speaking as we do, right?

It seems some would prefer, or some are more comfortable with us speaking with a stronger "Black dialect."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mmm-hmm, sure.

Bryant Gumbel: My dad impressed that upon us.

We had gone down one night to, to see my Uncle Archie.

And Uncle Archie started going, "Hey, what's happening, what's happening?"

And I'll never forget it.

My dad came back to the car, he said, "You see what your Uncle Archie did there?"

I said, "No."

He said, "Let me explain."

He said, "Your Uncle Archie's an educated man."

He said, "Don't ever talk down to somebody by pretending you're not."

And so, to this day, I think of it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And it's great advice.

Bryant Gumbel: And if people want to say, "Hey, you know what, you're trying to sound something," I feel bad for them.

Because that means sounding Black means sounding ignorant, and sounding smart means sounding White?

I don't buy that equation, I don't buy that correlation.

Suzanne Malveaux: Hey there, welcome to News Room International.

I'm Suzanne Malveaux.

We're taking you around the world in 60 minutes.

Here's what's going on now... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Suzanne Malveaux is one of America's leading broadcast journalists, an intrepid reporter, she spent more than a decade as CNN's White House correspondent interviewing Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama.

Like Bryant Gumbel, Suzanne has roots that stretch back to Jim Crow Louisiana, where both of her parents were raised, she grew up hearing stories about their experiences under segregation.

Suzanne Malveaux: My mother would talk about the walk that she had to make to school, to get to the colored school, or the Black school.

She would pass the church that was Whites-only.

She'd pass the schools that were Whites-only.

She passed the pools that were Whites-only.

She used to walk with her brother, and he used to get beaten up every day.

She cried and they would run home together.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: These stories helped shape Suzanne's sense of her own identity as an African American.

Nevertheless, she's aware that that identity is not immediately apparent to most people.

So, when someone asks you, "Who are your people, where do you come from," you know that question?

Suzanne Malveaux: Yes.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Meaning, "What are you," what do you say?

Suzanne Malveaux: People are really confused about what I am, and I tell them I'm Black.

Both my parents are a combination, I guess, that Creole/New Orleans mix.

And so, in our immediate family, two of us will identify as African-American, two identify as people of color, and two identify as Black.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh... Suzanne Malveaux: And I'm one of those who identify as black.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What do you get mistaken for most?

I bet nobody guesses that you're Black.

Suzanne Malveaux: Well, you know, it's funny, because I think most Black people know I'm Black.

They can see it.

But yeah, I mean, I can go anywhere in the world and they think, like, I kind of blend into wherever it is that I travel.

So, when I'm in Egypt, they think I'm Egyptian.

When I was in Kenya, they thought I was half-Kenyan, half-White or European.

So, it almost depends on where I am, and then people kind of assign me that identity.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Suzanne told me that while she had some trouble explaining these confusions in her youth, she's long since adjusted.

In fact, she's even used them, on occasion, to her own advantage.

Have you ever been in a conversation when people didn't know you're Black, and they were saying bad things about black People?

Suzanne Malveaux: Oh, yes.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, you're like a double-agent?

Suzanne Malveaux: Yes, that has happened before.

Oh, yes, then comes the surprise when you actually tell them.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You say, "I'mma go Black on you."

Suzanne Malveaux: I did a story where, it was the 2008 election, and what people were thinking about Barack Obama, and people, you know, freely were really kind of throwing out some racial slurs and things like that, and I think in that moment, I think they didn't know.

They didn't realize that yes, there was a Black woman in front of them who was collecting information, and they were speaking very freely, and I used it, I did use that to my advantage.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Did you tell them that you were Black or no?

Suzanne Malveaux: Not in that circumstance.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No, right, you did the right, you were a good reporter.

Suzanne Malveaux: I told the story, I got the story, yeah.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Yeah, my father's side seems to have more information there.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: My third guest is Tonya Lewis Lee.

She's had a diverse and productive career as an author and television producer.

Tonya Lewis Lee: We really need to see ourselves represented... Henry Louis Gates Jr: While also serving on the board of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Tonya was born in Yonkers, New York.

Like the Gumbels and the Malveauxs, her parents came north in search of opportunities and they'd found them.

Her father, George Ralph Lewis, is a Black business pioneer who climbed the executive ladder at Philip Morris.

Her mother Lillian is a member of "The Links," an influential organization, comprised of outstanding women of color.

Needless to say, the two set high standards for their children.

Tonya Lewis Lee: They were pretty strict disciplinarians.

I think, you know, having moved from Virginia to New York, um, and my father you know entering corporate America at a time when, you know, Black people were just entering corporate America, you know, they had expectations that their daughters would, you know, represent them well.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Um-hum.

Tonya Lewis Lee: And so they didn't mess around.

You know, we were starched and well-dressed at all times and clean and neat, and you know schoolwork was absolutely the most important thing.

Education was everything, and there wasn't too much time for foolishness.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: While Tonya developed creative aspirations early on, her father had other ideas.

So when it came time to choose a career, the pressure was intense, but Tonya never lost sight of her goals.

Tonya Lewis Lee: My parents had an idea that it was going to be business school or law school.

You know, I kind of thought I wanted to work in television.

I wanted to produce, but that was not something we did.

So I figured I could help people some way if I went to law school.

I came home and told my father, "I think I'll go to law school and maybe be a civil rights lawyer."

He was like, "No, no, that's not what I was thinking."

You're going to be broke for the rest of your life, you know.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Somebody else can help all those people.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Exactly.

So, I kind of went to law school to, to, you know, kind of please my parents, but I figured out how to back my way into doing all the things I wanted to do.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Each of my guests tonight grew up in a tightly-knit family and each feels deeply connected to their African American heritage.

Yet, like so many people, Bryant, Suzanne, and Tonya actually know very little about the ancestors who fill the branches of their family trees.

It was time to meet them.

I started with Bryant who was especially eager to uncover his father's roots.

Bryant Gumbel: First and foremost, I'm my father's son.

People who know me are, and who knew my father, are ever amazed at how much I'm like my dad.

And he was the foremost influence on my life, and you know, the real hero of my life.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant's father died of a heart attack when Bryant was only 23 years old, his death left an unfillable void.

It also robbed Bryant of a deeper knowledge of his family, because while he knew his grandfather, Richard Dunbar Gumbel, the two weren't close.

Bryant Gumbel: I had a strange relationship with my grandfather, my father's father.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Why?

Bryant Gumbel: When my dad died, my grandfather didn't come to the funeral.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Hmm.

Bryant Gumbel: Now, I heard a variety of alibis, excuses, reasons, some that he hated to fly, scared to fly, some that he couldn't accept that his son was dead, whatever, but he didn't come.

That's all I knew.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And that was enough.

Bryant Gumbel: That was more than I needed.

So, I basically canceled him out of my life.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant's grandfather died in 1980 but their ties had been cut almost a decade earlier and Bryant told me he knew very little about Richard's life and nothing at all about his roots.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Had you spent much time with your grandfather before your father died?

Bryant Gumbel: Only to the extent of whenever I went down to New Orleans, when I was down South, I'd go see him.

He was always playing cards at the Autocrat Club.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The famous Autocrat Club.

Bryant Gumbel: All he'd do is play cards at the Autocrat Club and gamble.

It wasn't like the Autocrat Club was a place for kids to hang out.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

Bryant Gumbel: And he wasn't exactly gonna say, "Oh, you know, let's go outside and throw the ball around."

No, no, he had a next hand to play.

You know, he'd have a drink to do... Henry Louis Gates Jr: Sure.

Bryant Gumbel: And that's all he'd do.

He was a gambler, he'd been a gambler all his life.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You never heard any stories about his early life in New Orleans?

Bryant Gumbel: Nnn-nnn.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Well, let's see what we found out.

Would you please turn the page?

Bryant Gumbel: That's him, that's him.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's Richard as a young man.

He looks like a smooth character to me.

Bryant Gumbel: Yes, that fit, that fits the persona.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: According to his obituary, guess what's highlighted, his membership in the Autocrat Club.

Bryant Gumbel: What a shock, what a shock.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: In fact, did you know he was a founding member of the Autocrat Club?

Bryant Gumbel: I'm not surprised, but no, I didn't know that.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Beyond the Autocrat Club, Richard left behind very few traces.

But in the New Orleans city archive, we found the clue to his roots: his marriage license, which listed the names of his parents.

Bryant Gumbel: "License is hereby granted to join in the bonds of matrimony, Richard Dunbar Gumbel, son of Jack Gumbel and Valentine Prevost."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Jack and Valentine are your great-grandparents.

Bryant Gumbel: Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it like to see that?

Bryant Gumbel: I'm stunned, I really am.

Um, this is the first time I've ever heard of Jack Gumbel.

First time I've ever heard of Valentine Prevost.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We wanted to learn more about Jack and Valentine, but immediately we ran into a wall.

In the 1910 census, we found Valentine in New Orleans living with her son Richard.

But Jack Gumbel wasn't living with them!

In fact, we found no record of anyone named "Jack Gumbel" in the entire state of Louisiana.

It was a mystery.

So we broadened our search and began looking for any man named "Gumbel" about the right age to be Bryant's great-grandfather.

Bryant Gumbel: Cornelius Gumbel!

Henry Louis Gates Jr: In 1910, there was a man named Cornelius J. Gumbel, the only Gumbel living in New Orleans at the time who was anywhere near the right age to be your great-grandfather.

And of course, there's that middle initial, J. Bryant Gumbel: So, he's Jack.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mhmm.

Bryant Gumbel: The reason I'm smiling with a degree of recognition is I heard once upon a time that they had debated naming me Cornelius.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, no kidding?

Well, now you know why.

Bryant Gumbel: I wondered where it came from.

Thank God they didn't.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Identifying Cornelius resolved one question in Bryant's family tree.

But we still had to figure out why Cornelius wasn't living with Valentine and her son Richard?

The answer was that Bryant's great-grandfather had a household of his own.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We discovered that he was living with an entirely different wife and family.

Bryant Gumbel: Huh, same guy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Same guy.

Bryant Gumbel: Oh.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What do you make of that?

Bryant Gumbel: Uh, I'm, you know, uh, I'll keep that to myself.

I'll be damned.

That's bizarre, more than a little bizarre, wow, Cornelius Jack.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant's great-grandfather was turning out to be a very secretive man and as we combed through the records, we uncovered what may have been a reason why.

In the 1910 census, Valentine and Richard are listed as mulattos.

But that's not how Cornelius was listed.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Can you tell me what that letter is next to your great-grandfather Cornelius's name?

Bryant Gumbel: It's a "W."

Does it stand for women or White?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: White.

Bryant Gumbel: Thus the double life.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, this wasn't something that you heard when you were growing up?

Bryant Gumbel: No, God, no, nnn-nnn.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Cornelius's race may well explain his absence from Valentine's home.

Color inflected virtually every aspect of the social order in Jim Crow Louisiana.

But even so: Bryant's great-grandparents did have some kind of relationship, and it was acknowledged in one very significant way.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right now I want to focus on Cornelius's love life, his romantic life.

Bryant Gumbel: Evidently an active love life.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Specifically, on the relationship between your great-grandparents.

Even though they were never married, and even though they were on different sides of the color line their son, your grandfather, either took the Gumbel name or his mother gave it to him.

Bryant Gumbel: Oh.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yes.

Bryant Gumbel: Oh.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, the relationship between Cornelius and Valentine wasn't a secret, and so, you ended up a Gumbel.

So, they had an out-of-wedlock relationship, but she gave the child the daddy's name.

Bryant Gumbel: I could have wound up with her name.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, you could've.

But you didn't.

What do you make of that?

I mean, I think it's a fascinating story.

She wanted people to know.

Bryant Gumbel: It's pretty stunning.

I wonder did she do it for her own reasons to, um, make it seem like she wasn't a woman in shame, having a baby out of wedlock?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I think that she wanted the son to know his daddy.

It's also... Bryant Gumbel: That's noble.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You know, it's also saying, "You know, we had a love relationship, and that's your daddy.

And you are, by rights, his son, and therefore you have a right to his surname."

So, it's very assertive on her part.

Bryant Gumbel: Yes, yes.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, does this change the way you think about your father's family?

Bryant Gumbel: It's a lot more complicated than I thought.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mhmm.

Bryant Gumbel: Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What would your father have thought?

Bryant Gumbel: I've no idea.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: But it's interesting to think about.

Bryant Gumbel: I mean look, let me put it this way: if he ever knew any of this, he never shared it with me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant now knew exactly how his family name had crossed the color line.

But where had the White Gumbels originated?

As we dug deeper into Cornelius' story, our search took us far from New Orleans.

Now, take a look at this document.

It comes from the vital records for San Francisco, California.

Bryant Gumbel: "Deceased: Cornelius J. Gumbel.

Date of death: September 22, 1959."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We're looking at the death record for your great-grandfather.

Can you read the transcribed section below?

Bryant Gumbel: "Name and birthplace of father: Cornelius...

Germany."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Did you ever think you had German roots when you went to Germany, did you feel at home?

Bryant Gumbel: No, no, absolutely not, I'll be damned.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Cornelius' father was also named "Cornelius," though he sometimes went by "Karl."

He is Bryant's second great-grandfather.

And once we learned that he was born in Germany, we began to search for evidence of his journey to America and we found something exceptional.

Bryant Gumbel: Passenger list for the Ss Germanic.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: How many people, particularly African-Americans, can find the passenger ship that their White ancestor came on?

Bryant Gumbel: During the Civil War.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: September 7, 1863.

Can you tell me whose name you see there?

Bryant Gumbel: Karl Gumbel.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: This document represents the moment your Gumbel ancestors arrived in America.

Bryant Gumbel: It's, it's, it's wild, absolutely wild.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Karl Gumbel came to New York when he was just 16 years old, on a ship that had departed from the city of Hamburg, in what is now northern Germany.

We traced his roots to a small town known as Albisheim, where we uncovered a most surprising fact about Bryant's heritage.

Bryant Gumbel: "The year 1808, January 16 at 9 o'clock in the morning, appeared Gimpel, Elias, Jew."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: According to this document, your fourth-great-grandfather, Elias, was Jewish.

Bryant Gumbel: Wow, isn't that something?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: So, when you were growing up, no rumors that you had Jewish ancestors.

Bryant Gumbel: No, uh-uh, uh-uh, uh-uh.

I mean, we always had Jewish neighbors.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Well, you are of German Jewish descent.

Bryant Gumbel: I'd, I had no idea, I had no idea.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We had now taken the Gumbel family back six generations to a Jewish community in the 1700s!

But we had done it all via a paper trail that stretched across continents and involved multiple name changes.

We wanted to make sure we were right.

So we turned to the one thing that could tell us with certainty: DNA.

Bryant Gumbel: "Bryant Gumbel's European admixture."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What do you read there, my brother?

Bryant Gumbel: "7.1% Ashkenazi Jew."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You are 7% Ashkenazi Jewish.

Bryant Gumbel: I'll be damned.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And this amount of Jewish DNA, Ashkenazi Jewish DNA, is roughly equivalent to what you would inherit from one great-great-grandparent of full Jewish ancestry.

So, we believe that your German ancestors were in fact Jewish.

Bryant Gumbel: Wow, look, it's gonna make great conversation.

I mean, it's like, golly.

7% Ashkenazi Jew.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, and you have the paper trail.

See, a lot of people take these DNA tests, and you get an anomalous result, you go, "Where the hell did that come from?"

But you're one of the rare... Bryant Gumbel: You got the paper trail to say... Henry Louis Gates Jr: They overlap, exactly.

Bryant Gumbel: So, you can actually prove it.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We can prove it, both ways.

Bryant Gumbel: Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: DNA don't lie, as the brothers say.

Bryant Gumbel: I'm, I'm, I'm overwhelmed.

I mean, I really am.

I wish, I so much wish I could've shared this with my daddy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, I wish you could too.

Bryant Gumbel: My daddy, see, my daddy is the kind of guy who would have appreciated this more than, more than anybody you can imagine.

My daddy would have loved this stuff, yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, I'm sorry, buddy.

Bryant Gumbel: Yeah, so am I, but I'm my daddy's kid.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Like Bryant, Suzanne Malveaux's roots lie in Louisiana.

Her ancestors have lived there since the 1700s and since she was a girl, Suzanne has longed to know about their lives.

She told us that her father had researched his family intensely before reaching an impasse.

Suzanne Malveaux: After Alex Haley's "Roots" came out, my dad kind of dusted off the big chart that he made.

He was very passionate about finding out our ancestry, and what the folklore was, and what he found out, was that there were two slaves that had French names, Laurent and Jean Baptiste and we suspect that maybe they came on a ship.

But we're not exactly sure, like, how they ended up with their French names.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: As it turns out, Suzanne's father did an excellent job, up to a point.

Using census data and vital records, we were able to confirm much of his research, tracing his family back six generations, to a man named Laurent Malveaux, who died in Louisiana around 1830.

"Laurent" was the name that Suzanne's father had ascribed to one of his enslaved ancestors.

But that's where his research started to break down.

Suzanne Malveaux: "Laurent Malveaux, free man of color, lately died in said parish and left therein his estate."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You're looking at the will of your fourth-great-grandfather.

Suzanne Malveaux: Wow, he was free.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You have free ancestors on the Malveaux line, going back at least to your fourth great-grandfather, who was a man of color, and free.

Suzanne Malveaux: It's amazing, it makes me feel really fortunate.

So many others suffered, and we were spared some of the crueler aspects of our nation's history, you know?

And we were able to somehow, in some way, prosper.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Laurent Malveaux was prosperous indeed.

In 1830, he was running his own plantation!

But Laurent's story was far more complicated than it seemed at first.

This is the inventory section of your fourth-great-grandfather's estate.

It lists and values all the property that he owned.

Suzanne Malveaux: "A Negro man named John, about age 30 years, with his two children to wit William, a boy aged about seven years, and Desire, a girl aged about three years."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your fourth-great-grandfather was a slave owner, a Black slave owner.

Suzanne Malveaux: That's really tough, it's hard to breathe, I'm having a hard time breathing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It may be hard to comprehend, but Laurent's story was not as unusual as you might think.

In 1830, there were over 900 Black slave-owners in Louisiana, which means roughly 40% of the state's free Black households contained slaves!

Their rationale, in many cases, was to protect family members.

But sometimes the motivation was purely economic: to succeed as a planter, White or Black, you needed the labor of slaves.

But as we dug deeper into Laurent Malveaux's papers, we found that not all of his slaves were treated the same, in 1818, he purchased a 40-year-old woman named Constance from his neighbor.

Soon after, Laurent freed Constance, but she remained in his household.

And more than a decade later, he made an astonishing declaration about their relationship.

Suzanne Malveaux: "Your petitioner is desirous to emancipate his two slaves to wit, a Negro girl named Celesie aged about 15 years and a Negro girl named Hortense aged about 12 years, the reason by which he is induced to emancipate his said slaves is that he is the father "right" of said slaves by a free woman of color named Constance formerly the slave of your petitioner."

So, he and Constance have two children.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mmm-hmm.

Suzanne Malveaux: So, he buys a slave, and he and this slave woman have two children?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, and then he frees the mother of his children and then frees his children.

Suzanne Malveaux: Do we know if they had a relationship?

Did they have a real, loving relationship?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We only know what the documents tell us.

He freed her, he freed the children.

Many slave owners never admitted that they fathered a slave's child.

Suzanne Malveaux: Maybe these children were special to him in some way.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We don't know.

All we can do is look at those cold, dry, black-and-white documents and wonder.

Suzanne Malveaux: It's a complex story.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, but one of the hidden aspects of Black history is that we had Black slave owners too.

Nobody wanted to talk about it, people found it embarrassing, but this is a fact of American history.

Suzanne Malveaux: If I could go back, I'd love to understand what all of them were thinking, on both sides, 'cause that's, everybody has that potential.

We are human beings, and we're all capable of cruelty and goodness.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right.

Suzanne Malveaux: This is, this is a lot.

It is a lot.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Like Suzanne and Bryant, Tonya Lewis Lee has deep roots in the South.

But her roots don't run through Louisiana, they go through Virginia, into counties where enslaved Africans first arrived in the 1600s.

For Black Americans, this is one of the most historic regions in the nation.

And Tonya's family embodies multiple sides of that history.

On her father's lines incredibly, she has free Black ancestors stretching back to the 1700s!

Tonya Lewis Lee: My sister and I would joke, "You know, we come from royalty."

Somehow we feel and it's not royalty but there is a sense of knowing that there's something there.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yes, you're from free people color royalty.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Tonya knows a great deal about her father's roots because this part of her family tree was much celebrated.

Her maternal ancestry, however, was another matter.

Tonya Lewis Lee: On my mother's side I couldn't get a lot of answers.

I knew my great-grandmother very well, in fact she was like my bestie really, but if I pressed her too much about the past she would get very upset with me, particularly if I asked her like well, who was your grandfather.

She would say, "Who cares about that?

Why are you bringing that up?"

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Why do you think?

Tonya Lewis Lee: Um, I think it was painful for her in some way.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mhmm.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Yeah.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Silence is a common obstacle to tracing a Black person's roots.

Slavery and its aftermath, devastated Black families.

And some of our ancestors chose not to talk about the past because it was too painful.

As a result, so many family stories have been lost.

Fortunately, as we explored Tonya's maternal roots, we uncovered a phenomenal one.

It began with a pension application for a man named Edward Patterson.

He's Tonya's third great-grandfather, and his application, filed in 1899, allowed us to take her mother's family back before emancipation, revealing that they experienced what many of her father's ancestors did not.

Tonya Lewis Lee: "Bureau of pensions, Edward Patterson, Septa, Virginia.

Were you previously married?

I was never legally married but had a woman as a slave wife, Susan, who died around 1874.

Have you any children living?

Two.

Son named Charlie Patterson born about 1860, daughter Lizzie Green born about 1859.

I was a slave and I had no record of the birth of my children."

Okay, wow, hmm.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: What's it actually like to see that, to see an ancestor that old and to see his handwriting and to see the fact that they're listed as slaves?

Tonya Lewis Lee: You know, it's, um, it's empowering to me to be honest with you in some way.

It's because, but for him I wouldn't be here.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Oh, yeah.

Tonya Lewis Lee: You know it is emotional.

You know, it is.

There is an emotional piece to seeing it in black and white.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Tonya Lewis Lee: And so I'm thankful and it's just great to be able to, I wish I could touch it you know, but it's like touching it a bit.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, it is.

Tonya Lewis Lee: It really is.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Edward Patterson was born in Virginia around 1830.

That means he was in his early 30s when the Civil War broke out.

There was heavy fighting in the region where he was enslaved.

And Tonya naturally wondered what happened to him, the answer came as a startling surprise.

Tonya Lewis Lee: "Edward Patterson, is that Company F37 regiment US colored infantry?"

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yes.

Tonya Lewis Lee: "Appears on company descriptive book of the organization named above.

Age: 35 years.

Height: five feet, seven inches.

Complexion: dark.

Eyes: black.

Where born: James County, Virginia.

Occupation: farmer.

Enlistment: May 18, 1864 in Norfolk, Virginia."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mhmm.

Tonya Lewis Lee: So he was in the colored infantry?

What was this for?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your third great-grandfather fought for the North, fought for the Union in the Civil War.

Tonya Lewis Lee: That's great, that's really great.

I love that, makes me really proud.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You should be.

Edward was a volunteer, one of over 5,000 Black men from Virginia who served in the Union Army.

We don't know how he managed to escape slavery, he may have run away, or been liberated by advancing Union troops.

But we do know that in the summer of 1864, his unit saw combat in the Battle of New Market Heights, a notable Union victory.

Unfortunately, Edward was injured on the eve of the battle, an injury that would hamper him for the rest of his life.

Making matters worse, he struggled for years after the war to receive the pension that was his due.

This is a letter that we found in Edward's pension file.

It was written by a doctor named W.H.

Heart to the Court of Pensions on behalf of your third great-grandfather.

Tonya Lewis Lee: "The old man says he is now nearly 72 years old and suffers very much from rheumatism and at times can scarcely walk, has a wife nearly as old and disabled as he is, is very poor, has to work for their living and rent a little house to live in, has no team.

I've known the old man for a long time, have found him to be very honest and worthy old, colored man.

He asks in praise that your honor will do everything you can in right and justice to aid him as he cannot live but a few years more at most and if he should get much worse off than he is, he and his wife would have to be carried to the poor house to be taken care of where they would have but few comforts."

Wow, so this is him trying to get something.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Trying to get the pension.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Trying to get the pension, I guess Virginia didn't appreciate his fight.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No.

Tonya Lewis Lee: This makes me so mad.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Tonya Lewis Lee: It's just, it's just so unjust to me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Although Edward's health suffered greatly in his final years, there was a small piece of good news I could share with Tonya.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Guess what?

Tonya Lewis Lee: What?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: He got his pension.

Tonya Lewis Lee: He did?

That's good, I'm happy to hear that.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And you had no idea, no suspicion?

Tonya Lewis Lee: None whatsoever.

It never even occurred to me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mhmm.

Tonya Lewis Lee: I am grateful and extremely proud and know he went through a lot but it sounds like he was a man of conviction.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, and he volunteered.

Tonya Lewis Lee: And he volunteered.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: He could have just kept on running.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Could have, he could have.

Yeah, I mean he was a brave, courageous man.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: I had already traced Bryant Gumbel's paternal ancestry from a mixed race family in New Orleans to a Jewish community in Europe.

Now it was time to look at his maternal ancestors, an investigation that sent our researchers back to Louisiana.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That is the 1930 census for New Orleans, and can you find your mother's name?

Bryant Gumbel: Yep, Rhea, 1930.

The daughter of Adrien and Adele.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your grandfather Adrien was working as a laborer, and we know from other census records that he worked at a shipyard.

Do you have any memories of them?

Bryant Gumbel: Yes, I'm surprised he was a laborer, because if you ever saw a regal, haughty man... Henry Louis Gates Jr: It was he.

Bryant Gumbel: Yeah, yeah, I mean, yes.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Well, I want to show you what we found out about this regal, haughty man.

Bryant Gumbel: Okay.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Would you please turn the page?

You'll see it starts with you on the bottom.

Bryant Gumbel: Right.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Then goes up to your grandfather Adrien Lecesne, and up to a man named Martin Lamotte.

Martin Lamotte is your great-great-grandfather.

You ever hear of him?

Bryant Gumbel: No, born in 1831.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: 1831 is just over three decades before emancipation.

At that time, Louisiana's Black population totaled about 110,000 people.

More than 85% of them living in bondage.

So it was reasonable to assume that Martin Lamotte was born into slavery.

But as we searched the state's archives, we found something that stunned us.

Bryant Gumbel: "Martin Lamotte, age 25.

Recorded upon act of manumission found before the notary public of the parish of Orleans on the 1 of August 1840."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Manumission is the process by which a slave became free.

That is the record of your ancestor becoming free.

Bryant Gumbel: I'll be damned.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That is as rare a document as you'll ever find on any Black family tree.

Bryant Gumbel: I'll be damned.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: After he was granted his freedom, Martin became a bricklayer and a carpenter, significant accomplishments for an African American at that time.

But when the Civil War broke out, Martin did something that many Black people would find very difficult to understand.

Bryant Gumbel: "Roll card, 1 native guards, 1861, Confederate.

Martin Lamotte."

He's a Confederate soldier?

He's a rebel?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: The Native Guards were free men of color, when the war broke out, declared their loyalty to the Confederacy.

Did you know that any Black men served the Confederacy?

Bryant Gumbel: No, no, I had no idea, I had no idea.

This is screwy, this is screwy, I'll be damned.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant couldn't believe that one of his own ancestors would have willingly joined the Confederate Army.

But the evidence was undeniable.

Martin's unit even published their intentions in a New Orleans newspaper.

Bryant Gumbel: "We the undersigned, natives of Louisiana, assembled in committee, have unanimously adopted the following resolutions, resolved, that the population to which we belong, as soon as the call is made to them by the governor of this state, will be ready to take arms and form themselves into companies for the defense of their homes, against any enemy who may come and disturb the tranquility."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You're looking at a call to arms written by a group of prominent free men of color.

Bryant Gumbel: May I humbly suggest, they didn't write this.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: They wrote it.

Bryant Gumbel: No way, no, no!

Henry Louis Gates Jr: They organized themselves... Bryant Gumbel: I'm guessing they got a bunch of brothers together, and they wrote this up, and they said, "You will sign this."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: No, about 1,500 free Black men voluntarily signed up for the 1st Native Guards, including Martin Lamotte, your great-great-grandfather.

The devil made him do it.

Bryant Gumbel: I, I just can't imagine.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: "Sign this piece of paper!"

Bryant Gumbel: Yeah, "You've got two choices: you can sign this, or we can, you know, point out your death certificate."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We'll never know for sure why Martin volunteered.

But as a free Black person living in a slave state, he might have felt he had to show devotion to the government that now controlled his fate.

It's certainly possible that he had no real loyalty to the Confederacy.

In any case, his loyalty was never tested.

About a year after his unit was formed, the Union attacked New Orleans and the city fell.

We wondered what happened to Martin, the answer lay in the records of the Union Army.

Bryant Gumbel: He changed uniforms.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: He changed uniforms.

Bryant Gumbel: He became a free agent.

Martin Lamotte, signed up.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your second-great-grandfather, now he's serving with the Union Army as.

Bryant Gumbel: Of course he did, of course he did.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: A corporal, what do you make of that?

Bryant Gumbel: Hey, smart man.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Martin joined the Union Army on the 2nd of July, 1863.

He was one of hundreds of Black Confederates who switched sides as soon as they had the chance.

And though he never saw combat, Martin reaped the benefits of the Union victory.

He went on to become a New Orleans police officer.

The arc of his life is remarkable to contemplate.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: He grew up a slave, he gained his freedom, went on to fight for the Confederacy, and then for the Union, and eventually served on a police force during Reconstruction.

He must have been a brave man.

Bryant Gumbel: You think brave man?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, I think, well, he was a practical man.

Bryant Gumbel: He was a survivor.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We had already taken Suzanne's roots back six generations to Laurent Malveaux, the Black slave-owner who died in Louisiana around 1830.

We wanted to go further.

Suzanne's father was convinced that the Malveaux name originated in France, meaning that somewhere back in his family tree, a White man of French descent had fathered a child with a woman of African descent.

While this idea seemed plausible, we couldn't find a record to support it.

So we turned to DNA and looked at Suzanne's father's Y-chromosome.

The Y-chromosome is passed from father to son in an unbroken line.

Which means it could lead us back to the place where the male Malveauxs originated.

Are you ready to see what we found?

Suzanne Malveaux: I want this mystery solved.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: All right.

Suzanne Malveaux: Yes, yes.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Please turn the page.

So, this test shows where your father's-father's-father's people came from back thousands of years.

What's it say?

Suzanne Malveaux: "Sub-Saharan African."

That's amazing.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your Y-DNA goes to Africa, does this surprise you?

Suzanne Malveaux: Well, yes, because we always thought there was somebody from France.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Which was logical.

Suzanne Malveaux: That was the story.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Which was logical.

Your ancestor was fathered by a Black man, and the proof of it is that that Y-DNA goes straight back to Africa.

Suzanne Malveaux: Wow, wow, that was the story that just kept going.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: DNA had answered one question, only to raise another, if the Malveaux male line extended in an unbroken chain back to Africa, when did they start mixing with Europeans?

Our search led us to the marriage record of Suzanne's third great-grandfather, a man named Jean-Baptiste Laurent Malveaux.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Can you read whom he married?

Suzanne Malveaux: Charlotte Rochon.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Have you ever heard that name, Charlotte Rochon?

Suzanne Malveaux: Um, it, there's some friends, family friends who are Rochons.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah, well, they're related to you.

Charlotte Rochon is your third-great-grandmother.

Suzanne Malveaux: Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And let me show you what we learned about her.

Suzanne Malveaux: Okay.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Would you please turn the page?

Suzanne, here's the 1850 census from St.

Martin parish.

This would have been recorded five years after Laurent and Charlotte got married.

Suzanne Malveaux: Laurent Malveaux, age 46, color: Black.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Black.

Suzanne Malveaux: Charlotte, age 38, color: mulatto.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's right and what's that tell us?

Suzanne Malveaux: She's mixed.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Ding!

Charlotte Rochon had White ancestors.

Suzanne Malveaux: Wow.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Charlotte Rochon is the first person on the Malveaux line whom we could identify as having European roots and she led us back another four generations, back to a man named Charles Rochon.

Both Suzanne and I were astonished where we found him.

Suzanne Malveaux: Mobile, Alabama?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mobile, Alabama, 1733.

Suzanne Malveaux: Geez.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Could you read the section that we pulled?

Suzanne Malveaux: "Serving as parish priest in Fort Conde, Mobile, buried the late Charles Rochon body who died the previous day after he officially received the sacraments/last rites of the church, buried Henriette Colon, Lord Rochon's wife."

Henry Louis Gates Jr: They are your seventh-great-grandparents.

Suzanne Malveaux: Geez, seventh-great-grandparents, are you kidding me?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Great-great-great great-great-great-great.

Suzanne Malveaux: That is crazy, it was?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Read that out loud.

Suzanne Malveaux: How many greats?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Seven.

Suzanne Malveaux: Great-great-great great-great-great-great.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's right.

Please turn the page.

Take a look at that map.

Do you recognize any of the names listed on this map?

Right there.

Suzanne Malveaux: Okay let me see, Rochon.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right, you're looking at your family's land from 1733.

Suzanne Malveaux: Oh boy.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: And this means that your seventh-great-grandfather Charles is one of the early founders of Mobile, Alabama.

Suzanne Malveaux: Really?

One of the founders of Mobile, Alabama.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Yeah.

Suzanne Malveaux: Really?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Really.

Suzanne Malveaux: Wow, that's amazing, I had no idea.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: When Charles Rochon arrived in Mobile, all of modern-day Alabama was part of the French colony of Louisiana.

So, as Suzanne suspected, she does have French ancestry.

But it didn't come to Mobile directly from France.

Charles took a much more circuitous route, a route that started in Quebec!

That is the baptismal record, get ready for that.

How many people can see that baptismal record for their seventh-great-grandfather?

Suzanne Malveaux: That's insane.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That is the baptismal record of your seventh great-grandfather Charles Rochon.

Suzanne Malveaux: We're in Canada now.

That's, that's incredible, I had no idea.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Your French roots run through colonial Canada.

Suzanne Malveaux: Never had any idea.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You wanted to know where your White people came from, this is it.

Suzanne Malveaux: It's absolutely incredible that you were able to find this.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Charles was baptized in Quebec City in 1673.

As a young man, he traveled along the Mississippi River, working as a fur trader, ultimately settling in what became Alabama.

On his way south, Charles married a woman named Henrietta, she's Suzanne's seventh great grandmother.

And she revealed an entirely new side of Suzanne's heritage.

Now, Suzanne, this is even more amazing than the amazing things that we found.

This is a baptismal record that we found in the archives of a church called the Immaculate Conception of Our Lady of Kaskaskia.

It's in French, and it's more than 300 years old.

Suzanne Malveaux: Oh, God.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Would you please read the translated section?

Suzanne Malveaux: I don't think I can pronounce this, this last name, but I will try.

"November 27, 1698.

Henrica, one month old.

Father, Jean la Violette Colon.

Mother, Catherine Exipakinoa?"

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Exipakinoa.

So, what does this name, Exipakinoa, suggest to you?

And the name of the church, Our Lady of Kaskaskia?

Suzanne, the Kaskaskia were one of the Algonquin-speaking native tribes of the Illinois River basin.

Suzanne Malveaux: We actually have Native American?

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You are one of the few African Americans who can actually identify descent from a Native American by name.

Suzanne Malveaux: Exipakinoa.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Exipakinoa, Catherine Exipakinoa.

Suzanne Malveaux: That's incredible.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's it.

You know her by name.

You don't have to theorize about this.

Your eighth great grandmother was a Native American.

Suzanne Malveaux: Wait till I tell my family.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We had now reached the end of the paper trail for each of my guests.

It was time to show them their full family trees.

Roots stretching back centuries and across continents, breaking racial barriers and demonstrating, palpably, that the African American experience is not monolithic, there are as many ways to be Black as there are Black people.

Bryant Gumbel: This is unbelievable.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mhmm.

Suzanne Malveaux: It's so rich.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: For each of my guests, and for me, it was an intensely moving experience.

Tonya Lewis Lee: I mean this, this is just unbelievable to me.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It's amazing.

Tonya Lewis Lee: I'm not here out of context.

I am here because of those who have come before and I am grateful to them.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Why don't we know about the complexities of the Black experience?

Why is this not part of the American narrative?

Tonya Lewis Lee: Often that's not the story people want to tell.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Mhmm.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Right, and I think unfortunately part of what we have done is that we live the life but we don't tell the story.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Right, that's a good way to put it.

Tonya Lewis Lee: Who else is going to tell our story if we don't do it, which maybe that's now my responsibility.

Suzanne Malveaux: It's so funny, there's an expression that we used to, we share in our family, that we pass along, "Laissez les bon temps rouler," let the good times roll.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Let the good times roll.

Suzanne Malveaux: Uh, there's that part of the family, and uh, and there's also the other part, which is really, you know, the complex and deep and um, also the painful part, right, of our American history.

So it's both.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: It's both.

Suzanne Malveaux: It's both.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: You exemplify the complexity of race, and capital, and property in American history.

You know, ironically.

Suzanne Malveaux: It, you can't separate any of it from the other.

It's all there.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Bryant, do you think that this knowledge, it will take a while to seep in, to digest and process, you think it will change anything about how you see yourself?

Bryant Gumbel: That's a great question.

I don't know.

I would like to think, would like to think, that as I get older, I become less judgmental and appreciate the complexity of life.

Um, this certainly gives me more reason to go in that direction, um, when I can.

Like everybody else, there's a big difference between my intentions and my actions, um, but you know, I've, I've mellowed with age.

Um, this certainly helps me mellow a little bit more.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: That's the end of our journey.

Please join me next time, when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots."

Narrator: next time on "Finding Your Roots," family trees disrupted by violent upheavals.

Actor, Lupita Nyong'o.

Lupita Nyong'o: Oh, my goodness.

I did not know that!

Narrator: NBA star, Carmelo Anthony.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: We're back 202 years.

Carmelo Anthony: Yeah, this is crazy.

Narrator: And political commentator, Ana Navarro.

Ana Navarro: Okay, so there's some family drama there.

Henry Louis Gates Jr: Big time.

Narrator: Revolutions and activist ancestors.

Carmelo Anthony: I'm speechless.

Narrator: On the next, "Finding Your Roots."

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: