Examine a 1950’s True Crime Case with Marcia Clark

Clip: Season 8 Episode 3 | 7m 13sVideo has Closed Captions

Marcia Clark revisits the true crime case of Bloody Babs.

Marcia Clark recalls her research into the details of the sensationalized Bloody Babs true crime case. After a wealthy widow was found dead in her Burbank home, the police arrested three suspects including Barbara Graham. The novelty of a woman on trial flocked hundreds of spectators, creating lines out the door of the Los Angeles Superior Court. With the death penalty looming, the case’s drama an

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

Examine a 1950’s True Crime Case with Marcia Clark

Clip: Season 8 Episode 3 | 7m 13sVideo has Closed Captions

Marcia Clark recalls her research into the details of the sensationalized Bloody Babs true crime case. After a wealthy widow was found dead in her Burbank home, the police arrested three suspects including Barbara Graham. The novelty of a woman on trial flocked hundreds of spectators, creating lines out the door of the Los Angeles Superior Court. With the death penalty looming, the case’s drama an

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Lost LA

Lost LA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[clip plays] LA doesn't just harbor criminals, it breeds crime storytellers.

In 1953, one case gave them everything they craved.

On the evening of March 9th, wealthy widow Mabel Monahan was discovered dead in her Burbank home, victim of an apparent home-invasion robbery gone sideways.

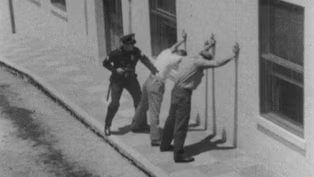

Police arrested three suspects, including 29-year-old Barbara Graham, accused of savagely beating the victim while her accomplices searched for rumored mob money.

The case had it all rama, violence, and a so-called femme fatale dubbed "Bloody Babs."

Graham's trial became a media circus, with reporters eager to play judge, jury, and executioner.

Seven years later, it still raises urgent questions, not just about guilt and innocence, but about how we tell crime stories in the first place.

Most people might not remember this trial or this case, but back in the 1950s, it really was a national sensation.

It was huge.

This case was their trial of the century.

It really did remind me of the Simpson case.

It's just people were standing in line to get a spot in the courtroom because it filled up quickly.

Those courtrooms are not very big anyway.

They were packed, teeth by jowl, every day in that courtroom.

It just had that kind of attraction for people who were fascinated by all the twists and turns.

The trial truly had twists and turns in it that were amazing.

A bombshell seemed to happen almost every day.

If I think of the standard true crime story, you don't often see the trial take center stage in the same way that it does in your book.

I wonder, what can we learn from that approach?

What can we learn from studying a true crime event through the trial itself?

To me, that's always the ultimate mystery.

How did they prove it?

They did not have any physical evidence.

They did not have any eyewitnesses.

Nobody turned.

For the first month or so, they had no one talking.

How did they convince a jury to not only convict Barbara, but to put her to death?

I had to get the transcripts.

I had to get my hands on that trial.

That's got to be a story right there.

Yes.

You start off the book with explaining how you went about doing that.

You had to go underground at what's now Grand Park in downtown LA to the county archives.

Yes.

That was so fun, I have to say.

I didn't even know it was there.

It was a trip to find out that the archives were, low and behold, subterranean, right behind the building that I worked in for 14 years in the DA's office.

There it was.

I went there, and it was fascinating.

It's this cavernous place.

It's huge, just like ginormously high ceilings, and stacked all the way to the ceiling with all of these court files that are multicolored on the edges that tell where they're from and where they go and what they are.

I thought, okay, those are not the files for Barbara's case because that was 70 years ago.

I'm hoping and praying they have it.

Ultimately, you got the transcripts from the state archives up in Sacramento.

Yes.

You also sourced it heavily from old newspaper accounts.

Of course, as slanted as that coverage was, that gives you the detail that you need to make the trial come alive.

Yes.

It gave me descriptions.

I was able to use the newspapers to get descriptions of who did what, bearing in mind always that when it came to Barbara, it was going to be exaggerated.

If she blinks, if she burps, if she yawns, every single thing was put through this magnifier and made a big deal of.

The truth of the matter is she is as stoic as could possibly be.

It's amazing, really, when you think about it, what she's up against.

Yes, but she maintained.

What part of it was the novelty that a woman was on trial and was facing the death penalty?

Yes.

That was a big deal.

That for them was truly, and it is still for us, man bites dog.

A woman accused of a heinous, violent crime, that's something that we don't see every day.

On top of that, when the woman is also beautiful and doesn't look the part, it would be different.

If she had looked like someone who would be rough around the edges, so to speak, she didn't.

She was actually accused of looking like a Hollywood starlet, by some, a showgirl, I think they said.

That didn't fit the mold either.

Then she's sitting next to these two thugs alk about Beauty and the Beast, and the contrast was something that they just couldn't resist.

On top of that, of course, it's a death penalty case, so it's as serious as it could possibly get.

Now, when you talk about the way the reporters were studying Barbara Graham with their eyes and their pencils, and making mountains out of molehills in terms of facial ticks or a crack of a smile, for instance, you must have been feeling déjà vu a little bit.

A little bit.

I did mention it.

I have to say, I didn't want to get into the Simpson case.

I also thought, look, if I don't draw this parallel, people are going to say, hello.

[laughs] Today, we call it clickbait.

Back then, they call it the scoop, but it's the same thing.

They're all looking for something new to say, and when they're covering on a day-by-day basis.

They were doing it on not only a day-by-day basis, but three times a day orning, afternoon, and evening news.

It was crazy.

As close as they could get to a 24-hour news cycle.

They were finding new things, and they had to keep digging up new things to say.

Yes, that was very similar to, at least I wasn't a defendant, but that's all I can say.

Your life wasn't on the line.

Yes.

Being the focus of that kind of attention, I had nothing but sympathy for what she was going through.

That's not to say that I couldn't look at the case dispassionately and say, look, I can see the evidence, and I know what happened here.

You can still say that wasn't fair.

I also had, luckily, access to all of the documents assembled by Walter Wanger.

He kept this archive of all of the communications he had regarding it.

For film production, and that ended up being a crucial documentary source for writing a nonfiction book.

Exactly right, because he actually amassed all of the true things.

He amassed Barbara's letters to her lawyers.

Not so much the lawyer's letters to her, but her letters to them.

Also he got the report that her lawyer, after she was convicted, Al Matthews, decided to hire an investigator.

He put together the report that gave so much information.

The jury never got to see.

It was critical stuff.

No one had ever published it.

I got my hands on that, thanks to Walter Wanger, and John True's original statement to the DA that was the first statement he ever made.

It was actually a transcribed statement with a stenographer that was wildly different than what he actually testified to.

No one knew it because they hid it from the defense.

You only had access to that because a film producer needed that for the film production.

Otherwise, it would have been lost to history.

Yes.

Ironically, it was a film producer who put all this stuff together, archived it, and kept it.

It was really wonderful and pouring through everything they sent.

I found these gems that no one had ever seen before.

Certainly not the jury.

It was amazing.

[music]

LA’s True Crime: Fact & Fiction (Preview)

Preview: S8 Ep3 | 30s | Discover how the True Crime genre was shaped by its deep historic legacy in Los Angeles. (30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 5m 8s | Michael Connelly credits his LA crime reporting experience as the foundation of his fiction writing. (5m 8s)

True Detective Helps in the Black Dahlia Case

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep3 | 1m 29s | True Detective Magazine was used as a tool to help hunt down the Black Dahlia murderer. (1m 29s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Lost LA is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal