VPM News Focal Point

Forfeiture | April 11, 2024

Season 3 Episode 7 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

How and why can the government take ownership of private property?

How and why can the government take ownership of private property? It can seize property under eminent domain when real estate or property taxes go unpaid or if land is needed to serve the public good. Can citizens do anything to stop it?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

VPM News Focal Point

Forfeiture | April 11, 2024

Season 3 Episode 7 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

How and why can the government take ownership of private property? It can seize property under eminent domain when real estate or property taxes go unpaid or if land is needed to serve the public good. Can citizens do anything to stop it?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANGIE MILES: The very definition of American freedom relies on laws that safeguard persons and property.

But what about exceptions that make it possible for the government to claim what is yours?

Forfeiture is our topic, and we'll consider the processes used by the police and local governments to legally take personal property.

We'll also visit with a community that is recovering some of what the government took away decades ago.

VPM News Focal Point is next.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪ ANGIE MILES: Welcome to VPM News Focal Point.

I'm Angie Miles.

In a country that embraces the ability to work hard and prosper, to acquire land and property that belongs solely to you, have you considered the ways government still has the right to lay claim to what is yours?

Eminent domain, police search and seizure, delinquent tax auctions, these are some of the areas we'll examine in our program.

Eminent domain is a process that allows governments to acquire private land for public use.

We examine the case of the last ferry to cross the Potomac River.

For more than 200 years, White's Ferry shuttled people and vehicles across the river.

But a 2020 court decision shut that down after the landowners on the Virginia side sued the boat company for trespassing.

Multimedia Reporter Billy Shields asked the question, could this be a situation that calls for government intervention?

JOY ZUCKER-TIEMANN: It is unconscionable to me that the economy here has suffered for over three and a half years because this ferry has been shut down.

BILLY SHIELDS: She means White's Ferry docked here on the Maryland side for almost four years while a property dispute in Loudoun County plays out.

CHUCK KUHN: It's a very unfortunate situation.

It ended up being a battle.

BILLY SHIELDS: The ferry ran for more than two centuries and could take more than a thousand cars a day.

Now it's not going anywhere.

AMY FLEISHMAN: Well, we were horrified because we use the ferry quite often to go to Virginia to go to restaurants and shopping.

BILLY SHIELDS: Some say a possible solution is to have Loudoun County appropriate the land under eminent domain to guarantee the ferry's access to the Virginia side.

LINK HOEWING: If eminent domain works, and that's what makes the solution happen.

That's great.

BILLY SHIELDS: The town of Poolesville, Maryland is especially affected.

It is a town surrounded by preserved agricultural land, and the ferry is its best link to Northern Virginia.

LINK HOEWING: We saw about a 20% drop in some of our businesses for a while in the kind of traffic they were getting.

BILLY SHIELDS: The owners of Rockland Farm won the right to shut the ferry down almost four years ago after they sued the ferry company for trespassing on private land, ending a use agreement that had lasted for decades.

A judge ruled that while there was public land, the ferry was given more than a century ago.

It was not clear exactly where that land was.

Now, Rockland Farm is trying to negotiate new terms.

LIBBY DEVLIN: All we're asking for is 50 cents a car.

There's many variations of that.

CHUCK KUHN: That would cause the rates for White Ferry to go up to an extent that people would not be able to use the ferry.

BILLY SHIELDS: The previous price to cross the river was $5 a car.

Poolesville residents like Joy Zucker-Tiemann continue to be frustrated as the ferry continues to sit unused within sight of the banks of Virginia, ANGIE MILES: A Loudoun County spokesperson says the county is not currently considering the use of eminent domain for the purpose of reestablishing ferry service.

The owner indicates he's willing to donate the ferry to Montgomery County if the county can guarantee they'll operate it.

ANGIE MILES: When it comes to the government taking all or a portion of someone's land for public use in exchange for a payment determined by the government, we wondered how people of Virginia view that practice, generally speaking.

DARRELL BIAS: Thats going against our freedoms, to tell you the truth.

If I bought that house in that location, it's mine.

Now, they need for me to agree to that, not just forcing me out of my home.

MARTHA HOWES: It could be all I have to leave to my children.

And that's some blood, sweat, and tears that go into those homes and lands.

And it's sad to see it go to a road, you know?

Or something the government says is good for me.

DONTAE SCARBOROUGH: How can you do that?

You can just come and just, that's like robbery.

I worked all my life to get to this one point and get my spot.

Like I got it and now you just going to say, "I'm building this and you just got to go now."

ZACHARY MYERS: It's necessary.

But for the government to decide the amount of money they're going to give you kind of feels a little shallow sometimes if it isn't a fair trade at all for the value of the land.

ROBERT IACOBACCI: If it is for the public good, a highway, mass transit, any of those situations, that's a consideration.

It's just for the enrichment of private companies, then no.

ANGIE MILES: Just as eminent domain grants our government the power to acquire private land for public use, civil forfeiture laws give police the authority to seize property allegedly involved in illegal activity.

To get the property back, the burden of proof typically falls on the owner, who must demonstrate innocence.

Over the years, Virginia has made efforts to reform these laws to provide more protection for property owners, as Multimedia Reporter Keyris Manzanares tells us.

MANDREL STUART: They took my money, counted my money, wrote me a receipt for my money, and after they tore my whole vehicle up, they sent me back on the road.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Under civil forfeiture laws in Virginia, police agencies can seize property if it's alleged to have been involved in a crime.

That's what happened to Mandrel Stuart in 2012 when Virginia State Police seized $17,550 from him during a traffic stop.

The Staunton native says he was driving in Northern Virginia with cash to buy restaurant equipment.

He was never charged with a crime.

MANDREL STUART: You have to prove yourself to be innocent when you're supposed to be already innocent and have to be proven to be guilty.

They already assume that you're guilty and you have to prove that you're innocent.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: In 2020, the General Assembly amended the asset forfeiture law to require a criminal conviction for all forfeitures.

But there are exceptions to this requirement.

Kirby Thomas West is a lawyer with the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit law firm based in Arlington.

KIRBY THOMAS WEST: Civil forfeiture is a subset of our property rights work, and it's extremely important part of that property rights work because it's a place where we see a lot of abuse and a lot of situations in which the government is taking private property from individuals who really did nothing wrong at all.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Thomas West says, the Institute for Justice gives Virginia a D- grade when it comes to their civil forfeiture laws.

KIRBY THOMAS WEST: The government is actually bringing the case against your property.

So civil forfeiture cases have these bizarre names like the United States versus a Ford F-150 or the Commonwealth of Virginia versus $21,000 in U.S. currency.

And that's the fiction that you know, we're not saying that you necessarily have done something wrong.

What we're saying is that your property has done something wrong.

Your property has been connected to some kind of crime.

There's also a financial incentive that is really pernicious, and that is that law enforcement often keeps the proceeds of civil forfeiture.

For example, in Virginia, law enforcement keeps 100% of the proceeds from civil forfeitures, and 90% of that goes back to the agencies that were doing the seizing.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: In fiscal year 2023, the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services reported that law enforcement agencies seized cash, cars, and property valued at more than 7 million dollars.

Chesterfield police received the most money back from seizures, nearly $800,000.

Virginia State Police received a little over $338,000.

Both agencies declined in-person interviews with VPM.

In a statement VSP said quote, "State police asset forfeiture fund spending is restricted to training, rent, and animal resources.

The one thing state police policy does not allow any asset forfeiture funds to be used on is salaries.

” When asked how they use civil asset forfeiture as a crime fighting tactic, Chesterfield police responded in an email saying, "Seizing cash, equipment, and drugs is a way to negatively impact or stop large scale narcotic operations."

KIRBY THOMAS WEST: The ultimate recommendation when it comes to civil forfeiture is always eliminate it.

The way that the government should take property is through criminal forfeiture, right?

No one should lose their property unless the government has borne its burden to actually charge them and convict them of a crime.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: In Stuart's case, he hired a lawyer and got his money back, but he still faced loss.

MANDREL STUART: Like I said, I lost my restaurant.

That was a big thing.

I lost my restaurant and I lost time.

You can't get that time back.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Reporting for VPM News, I'm Keyris Manzanares.

ANGIE MILES: The quest for a fair balance between law enforcement's powers and individual rights continues.

If you find yourself in a case of civil asset forfeiture and no criminal conviction is reached, you have 21 days to request in writing that your property be returned.

ANGIE MILES: VPM News Focal Point is interested in the points of view of Virginians.

To hear more from your Virginia neighbors, and to share your own thoughts and story ideas, find us online at vpm.org/focalpoint.

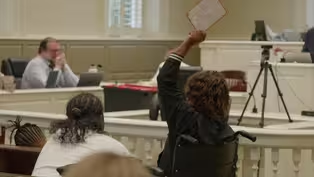

ANGIE MILES: There are few places in America as emotionally charged as a delinquent tax auction.

Standing or seated, sometimes side-by-side, are people excited to bid and get a bargain on a home or some land, a place to make an investment or build a dream, and people who are desperate and destitute, bracing for the loss of all they own and unable to stop it.

It might be a financial downturn or confusion about the tax process.

It could be complications of heirs' rights that arise when an elder dies without a will, but for each of the auction winners and property losers, there is a story.

LINDA QUARLES ARENCIBIA: I'm looking for some moss covered burial stones.

Yeah, this is it, this is it.

This is it.

I know when I first found the burial stone mound, it was a sense that my beginning is there, you know?

And if I detach myself from that, I detach myself in part from knowing who I am, how I came to be, who the folks were that I came to be from.

And so I don't like the idea of losing those connections.

My family has owned property in Louisa and Fluvanna counties since at least 1867, I would say, up to the present.

And it's only in this generation, in the last couple of years, that we stand at risk of losing that.

JAMES ELLIOTT: I think one of the difficult things about this job is that there are landowners that have fallen on tough times.

The cities and counties depend on revenue, primarily from real estate taxes, to pay the bills of the city and the county.

When people don't pay their real estate taxes, that puts a burden on the people that do pay their real estate taxes.

We do work out payment plans as often as we can, but if they don't live up to the payment plan, I really have no other choice but to proceed with the collection.

AUCTIONEER: I'd like to welcome you here to the James City County boardroom in Williamsburg, Virginia.

ANDREW NEVILLE: Once all of the required elements are met, then we schedule a public auction.

AUCTIONEER: 70 thou, 71, 72.

71 on the floor, got to be 72,000.

ANDREW NEVILLE: In an ideal situation, the high bidder would pay the purchase price, the money would be distributed to the various individuals, to the costs and the tax penalty and interest, and then if there weren't any judgements or deeds of trust, the access to the former owners.

AUCTIONEER: It's your way.

$66,000, thank you, sir.

High bidder.

ANDREW NEVILLE: And then the new owner of the property would hopefully do some good with the property, whether it needs mowed or whether they build a structure on it, but any good that they do with the property is a benefit to the community.

JOHN BROWN JR: We're thinking of starting a family estate.

So, where else would you like to start a family estate than where the family started?

We live in New Jersey now, we moved away, but this is still home for him, so this is history for us.

So it's not just we're just coming to invest in the land, we're from here, this is home, so it's just a trip to come buy back home.

CAMERON McKAY: This house has been the closest I have to a family home.

You know, my grandparents bought it new, and my mom lived here when she was in college, and they brought me here when I was a baby from the hospital.

And when my grandparents became elderly and needed full-time help in the home, I moved here to help take care of them.

So this is my grandparents, Larry and Barbara.

My wife and I are both disabled.

She's retired.

So, it's not like our income goes up commensurate with the cost of everything.

I mean, I knew we had some tax problems, but I didn't actually know that they were auctioning the house until a concerned neighbor called us yesterday and said, "Hey, are things okay?

You know, they're auctioning your house."

And it was kind of like, 'What?'

MICHELLE McKAY: I know the judge when I went to court that time told me that if you missed payments, they could automatically start proceedings.

But I was under the impression it was okay.

You know, I called them up and I explained what the situation was.

I got cancer in my kidneys, and I asked them if I could pause the payments and take care of what I had to take care of.

And she told me she'd pass it on, but she said, "Everything sounds good, and we'll get back to you."

They didn't call me back, and I just didn't pay 'cause I figured everything was okay.

And I didn't hear anything from them.

CAMERON McKAY: I had hoped that the man I spoke with from TACS knew that we were working to pay this, and if I had more than 24 hours, that I might be able to pay this, that maybe he could remove it, or maybe that he could even just accept what the realtor had told us, which was that it would be stopped if we had a contract.

But it seemed like that was just at their discretion.

AUCTIONEER: 290, got to go 25, looking at 290, 25.

ANDREW NEVILLE: In a situation where someone comes to the auction, what we will do is we will talk to that individual ahead of the sale.

We will look through all of the circumstances leading up to the sale.

AUCTIONEER: Our last call, 292, 295.

It's in house, you're away, sir.

ANDREW NEVILLE: Any of these judicial sales still have to be confirmed by a judge.

So in those circumstances, we would suggest they go to court, or if they feel the need to hire an attorney, to go to court and explain to the judge why the judge should not confirm the sale of the property.

CAMERON McKAY: You know, I am trying to be hopeful, I am trying to make plans, and, you know, I'll just have to see what the judge says, basically.

LINDA QUARLES ARENCIBIA: Here we've got a deed where Ann Smith buys my three-time great-grandfather, Spencer.

I have deep roots in Louisa, and my folk were not just sucking up Louisa air, they were enslaved here, but they became entrepreneurs, businessmen, and landowners.

Buy this parcel of land from Thomas Shepherd, who may have been the previous Josephs enslaver.

Well over 100 acres total.

I don't know that exact amount, because I still am wading through names and aliases and discovering land that I didn't know about.

Some years ago, my sons and I came by here, and there was still a structure and a closet, and now this, it looks to me like it's been demolished.

I did not know, one, that some of this land existed, two, that it was in jeopardy of being lost, until I found out from my niece, who's in Oregon.

I've lived in the state of Virginia for a while now, since at least 1990, and when I called the taxing authority and said, 'Why haven't I been notified,' "Well, we couldn't find you."

They found my niece, but they couldn't find me.

And then during a court hearing, we were told that one of the people that had been contacted was my Aunt Louise.

Aunt Louise died as a child, a 7-year-old, around 1930, and yet she was listed as one of several people that this authority had contacted.

Now I'm trying to go through the process of doing all of these things that I don't know about, like becoming executor.

A lot of the property, most of it was left intestate or with wills that were drafted but were never executed.

So, I'm going through that process.

What I would like to see in place is systems that help people who are potential heirs, or who discover they are heirs, to know how to navigate in a way that they don't lose.

ANGIE MILES: Several people told us that getting proper notice was a common problem.

By law, the collections attorneys must post notices in local newspapers and send letters by regular mail.

Another hurdle is embarrassment as people in tax trouble may not want to admit it.

In an online investment forum, a man claimed that a Virginia locality never notified him before selling his property for one-third of its value.

Several participants simply scolded him for falling behind in the first place.

Of the property heirs in our story, Cameron McKay's house sold for $125,000 less than a popular real estate site estimates its worth.

And of the 100-plus acres owned by Linda Arencibia's family, only one parcel was auctioned.

She says she has no idea who paid the taxes to save all the rest.

I'm joined now by Kajsa Foskey, who's an economic justice coordinator at the Virginia Poverty Law Center, where she works on heirs' rights, and she has a personal connection to this issue as she works to protect her family's land in rural Louisa County.

Also, we have Parker Agelasto, who is the executive director of Capital Region Land Conservancy.

Thank you both for being with us.

So we know that land forfeiture laws and heirs' property rights do pose some major challenges for many Virginians.

In your experience, how significant are these issues?

KAJSA FOSKEY: These issues are significant.

I think so many people underestimate the amount of land that was acquired in the reconstruction era, and since then we've seen land loss in the millions of acres.

ANGIE MILES: Parker, you want to weigh-in?

PARKER AGELASTO: Part of the confusion is because you don't have an agreement amongst family members about how to manage the property, and who is going to lead and run the point as the liaison with the local government for paying the taxes or managing the property.

KAJSA FOSKEY: I think that a lot of the solutions that are around our property tax system around addressing property issues don't always take into account the real lived experiences and the historical context that creates how Black families use and understand their land and care to manage their land in the future.

ANGIE MILES: Parker, can you speak about some of the changes you've seen in the way the law handles this?

PARKER AGELASTO: Virginia became one of the first states in the South to really adopt this uniform petition of Heirs Property Act, and it's an important thing, because it now puts into law the process by which heirs' property can be resolved in a court.

ANGIE MILES: Thank you both for joining us for this discussion.

(upbeat music) ANGIE MILES: You can watch the full interview on our website.

ANGIE MILES: Late last year in one of the first land reclamation projects of its kind, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe took ownership of more than 800 acres of land along the banks that bear their tribal name.

They did it through a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Multimedia Reporter Billy Shields caught up with the Chief of Upper Mattaponi to talk with him about its significance and their plans to preserve that land.

FRANK ADAMS: My name is Frank Adams.

I'm Chief of the Upper Mattaponi Tribe.

This is approximately 855 acres of reclaimed soil that used to be a sand and gravel mining operation.

And when this property came onto the market, came up for sale, we decided that we could buy this property if we could write a conservation grant.

So, we wrote a federal grant and was successful about six, nine months later.

So, we had a contract signed, and we used the grant funding to pay for the property, slightly more than $3 million.

Because it is a property that's in our cultural living area.

This is where we used to spend all of our time.

But we would like to, since we do have some river frontage and some lake frontage, we would like to establish a fish hatchery on this property to help generate and improve the habitat of the shad and blueback herring that migrate up the river every year, along with mussels and other things that clean the water and whatnot.

Took us 20 years to get federally recognized after we got a bill sponsored into Congress.

But being federally recognized opens up so many more doors, so many more opportunities for funding to purchase properties like this and/or just build our government, hire staff.

Being federally recognized has opened many doors for us.

It's a chore to manage 855 acres with the rains and the snowstorms and ice storms that occur occasionally around here.

So we have a crew, we have a maintenance crew, a grounds management crew that will come up and inspect the property to make sure the trees hadn't blown down or the roads haven't washed out or been compromised by heavy rains and whatnot.

And as global warming and climate change comes, storms are getting bigger and bigger.

So it is work for us.

We got our due diligence to do to keep this property open and available to our tribal citizens to be able to enjoy.

During the mining process, they dug pits, and the pits filled up with water eventually, after they got a certain depth, and when we purchased it, they were in the process of draining all these ponds.

There's three ponds still on this property, but we saw the value in the water and the wetlands for nature.

So we asked them, part of the contract was to leave these ponds unfilled and uncovered.

Eventually we'll start some ecotourism for our tribal citizens and/or the public, so they can enjoy this magnificent piece of property.

It's mostly a pine forest.

But we would love to plant some Indigenous trees on this property.

Trees that the Natives used hundreds and hundreds of years ago to survive with.

This property is right on the banks of the upper reaches of the Mattaponi River.

We have over a mile river frontage on this.

It's a hike to go down to the river, but the river is where life is for Native Americans.

ANGIE MILES: When do you have the right to own property and when is it right for the government to divest you of that property?

We've covered this issue from some varied perspectives in our program, but there is more to know and more to consider.

To watch the full interview about protecting heirs' property rights and to find resource links, visit our website at vpm.org/focalpoint.

While you're there, please share your story ideas and your feedback as well.

Thank you for joining us and we'll see you next time.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 2m 2s | A ferry run for over 200 years is now shut down (2m 2s)

The fight to hold onto family property in Virginia

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 17m 22s | Kajsa Foskey is fighting to protect her families’ land in rural Louisa County. (17m 22s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 10m 47s | The delinquent tax property auction is an everyday occurrence in America. Should it be? (10m 47s)

Reclaimed Land on the Mattaponi

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 3m 23s | An Indigenous tribe used a federal grant to reclaim 855 acres. (3m 23s)

Role of civil asset forfeiture in Virginia’s justice system

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep7 | 4m 3s | Exploring civil asset forfeiture laws in Virginia and its true role in our justice system (4m 3s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM