Finding Your Roots

Freedom Tales

Season 5 Episode 5 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

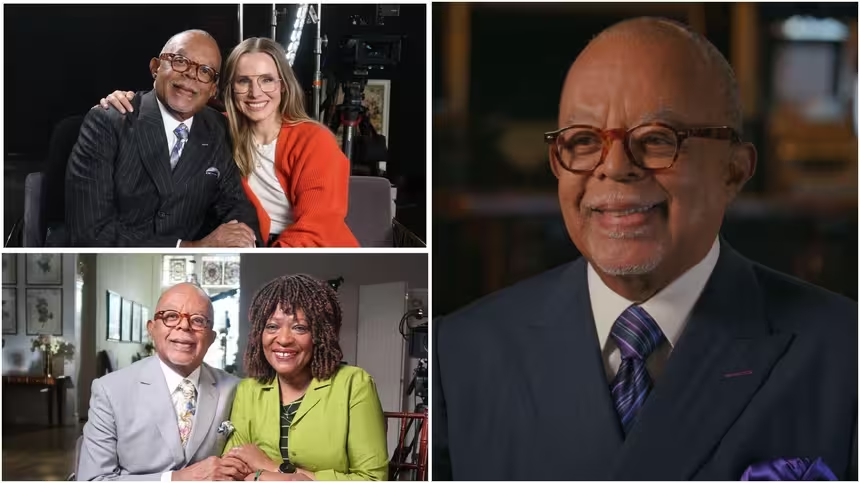

Dr Gates traces the family history of S. Epatha Merkerson and Michael Strahan.

Host Henry Louis Gates, Jr. delves deep into the roots of two African-American guests, actor S. Epatha Merkerson and athlete and television personality Michael Strahan. Both discover unexpected stories that challenge assumptions about black history.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Freedom Tales

Season 5 Episode 5 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Host Henry Louis Gates, Jr. delves deep into the roots of two African-American guests, actor S. Epatha Merkerson and athlete and television personality Michael Strahan. Both discover unexpected stories that challenge assumptions about black history.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGates: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to Finding Your Roots.

In this episode, we'll explore the ancestry of talk show host Michael Strahan.

And actor S. Epatha Merkerson... Two African Americans struggling with one of the greatest of all genealogical challenges: reconnecting roots that have been severed by slavery.

Merkerson: I've always wanted to know where we came from... Strahan: That's your family, your blood.

The next thing you know, you're gone.

They probably have no idea where you went.

I just, it makes me angry.

Gates: To restore what Michael and Epatha have lost, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists helped stitch together the past from the paper trail their ancestors left behind.

While DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old... And we've compiled it all into a book of life... Merkerson: This is amazing.

Strahan: It kind of takes your breath away.

Gates: A record of all of our discoveries.

This is your family tree in that record of slaves.

Merkerson: I'm blown away.

Strahan: Wow.

This is really one of the best things I've ever seen in my life!

Gates: Michael and Epatha are about to embark upon a journey that would have been impossible even a decade ago... A journey through the barrier that slavery erected on every African-American's family tree.

Erasing the names of our ancestors.

In this episode, we'll recover those names, long lost and forgotten... Revealing stories both astonishing, and uplifting.

(Theme music plays) ♪♪ ♪♪ Roberts: We have big news, our good friend Michael Strahan is joining us full time here... Gates: Michael Strahan makes everything look easy.

The legendary football player turned morning television talk-show host exudes an irresistible mixture of charm and charisma.

Combining an infectious smile, with a keen intelligence.

A blend that seems effortless, but it's not.

Michael's success belies years of hard work and herculean effort.

Work that began when he was just teenager.

Strahan: It kinda started when I was thirteen years old, and my brothers and their buddies making fun of me and calling me Bob, and I'm like Bob?

Bob meant booty on back, you know?

Because I wasn't working out.

I wasn't doing anything.

I was eating.

My booty was big, and they would say you can grab your wallet like that, you know, and all that kinda stuff.

Gates: Really?

Strahan: Yeah, really.

Gates: Oh, my God.

Strahan: So, I bought like the Jane Fonda workout tapes, because I was like, okay, she does exercises for your butt.

Gates: Sure.

Strahan: So I bought those tapes.

And that was, I loved it.

Gates: Jane Fonda was just the beginning.

Soon, Michael was doing push-ups and sit-ups.

And watching as much pro football he possibly could.

There was just one problem: Michael was living in Germany, where his father was serving in the Army.

A career in the NFL seemed like an impossible dream... But then his father intervened.

Strahan: My dad, after three years of eventually getting tired of me blocking the tv doing pushups and sit-ups, he said I'll just take you to the gym.

So, he used to buy Muscle & Fitness Magazine, create his own programs, and we'd go in almost every day, it felt like, as a thirteen-year-old, Gates: Right.

Strahan: And we'd work out.

And he told me one day, "I'mma send you back to the States, you're gonna stay with your uncle, you're gonna get a football scholarship."

And being naive and not knowing any better, I'm like, okay.

I don't know any better, and he sent me to Texas, the football capital of the world, to play football and get a scholarship.

Gates: For the first time?

Strahan: For the first time.

I had played when I was seven, eight and you know, a little bit earlier in my life, but I hadn't played football in years.

Gates: Michael's father knew what he was talking about.

After just one season of high school football, Michael got that scholarship, and more.

He soon found himself in the NFL, playing defensive end for the New York Giants.

But, despite his metoric ascent, Michael's unusual background meant that he was still learning the game, even as he became a professional... Strahan: It was like I was standing in the middle of traffic and stuff is zooming by.

That game Frogger, where you hop in front and you're trying not to get hit by a car.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: It's just how much stuff is crossing in front of your face, and you don't know how to decipher the information, because you really don't know where do you go from there?

Gates: Right, right.

Strahan: But after about my fourth year in the league, it just slowed down.

It, it went into ballet with Bears.

Gates: Oh, that's great.

That's beautiful.

Strahan: It was just very slow, big guys moving very slowly around, just dancing, and it became so slow that I could just sit and pick the game apart and once I knew, "Okay, he's lined up there and that guy's there, and they can only do these plays out of that."

So it's not coming to me, it's going over there, or okay, they're coming to me this time, be ready.

When I knew that I could pick out the play before it even happened, I could be pretty good at this.

Gates: Michael was more than "pretty good."

He's an all-time great... A hall-of-famer who holds the NFL record for sacks in a single season.

He's also one of the few athletes who seamlessly transitioned to television when his playing days were done.

Michael did it, in part, by bringing the same attitude to television that he brought to football... Preparing for his first hosting appearance like he was gearing up for the Super Bowl.

Strahan: I stayed up the night before, did not sleep, trying to think about things that I could talk about.

Gates: Right.

Strahan: And when I went on the show, it went by so fast.

Bam!

And I just thought oh my goodness, that was energizing, electric, I don't know what I said, but hopefully I get a chance to do it again because I know I can do it better.

Gates: Uh-huh.

Uh-huh.

Strahan: And twenty episodes later, I was asked to be the co-host.

Gates: My next guest is actor S. Epatha Merkerson, renowned for her star turns on "Law & Order," "Chicago Med," as well as stirring performances in an array of films and plays.

Merkerson: You're gonna carry this day with you for the rest of your life.

It'll be too much, baby.

Gates: Epatha is a fearless performer, blessed with a serene self-confidence and a willingness to take tremendous risks in her roles.

Characteristics that she says she inherited from her mother, who raised her, and her siblings, all by herself, with a truly independent spirit... Merkerson: My mother at 85 went skydiving.

Gates: No!

Merkerson: So that sense of adventure and belief in one's self is definitely from my mother.

Gates: So that's why you're crazy.

Merkerson: Exactly.

Gates: Did you go up in the plane with her?

Did you try to discourage her?

Merkerson: I did not discourage her because it was something that she wanted to do.

And after I saw the look of awe on her face as she descended I thought I have to try it.

Gates: And you did it?

Merkerson: And I'll never do it again.

Gates: Were you terrified?

Merkerson: I was.

Gates: I would never jump out of a plane.

Never.

For a million dollars I wouldn't jump out of an airplane.

Merkerson: But it was the look on her face, I'll never forget it.

And that's who she is.

At 76 she went back to college.

Gates: Really?

What an amazing person.

Merkerson: Yeah, she's an interesting woman.

Gates: Epatha told me she's drawn on her mother's example often never more so than when she moved from her hometown of Detroit to New York City, risking everything to become an actor.

It was 1978... And New York City was mired in a deep financial slump.

Epatha was 25 years old, living in Harlem on her own, desperately searching for work.

She soon found herself about as far off Broadway as you can get.

Merkerson: It was a little, tiny theater.

The building is now gone.

There's a high rise where the building used to be.

But it was like guerilla theater.

You'd go up three flights of stairs if the elevator didn't work, which it didn't sometimes.

The lights would go off sometimes when there was thunder.

We'd just hold still and when the lights came back on we'd continue working.

It was just, you know, that was the kind of theater we were doing.

Gates: Did your mom want you to come home ever?

Merkerson: She was definitely thinking that I could do something better, that I was smart enough to do something.

Gates: Like go to law school?

Merkerson: Or something.

Yeah.

Get a real job but when my mother came to see my first show and I left a check stub on my dressing table so she could see how much money I was making, Gates: Oh, that's cool.

Merkerson: And she broke her neck to see it and when she finally saw the money she has never said anything since.

Gates: After that it was cool.

Merkerson: That was it.

She's taking care of herself.

Gates: Epatha's mother was correct.

Her daughter was taking care of herself... And she would continue to do so.

Epatha has worked almost constantly ever since, and she's been amply rewarded for her talents... Moving fluidly between stage and screen... Winning an Emmy and a Golden Globe.

But for all she's accomplished, she remains deeply attached to her family, and she credits a large part of her success to their unflagging support.

Merkerson: They have always been extraordinarily encouraging.

And to this day, I have a brother, my brother Zephery, who's my biggest fan and he watches everything, so he'll call sometimes and go, yo, what was that?

We'll have this... Amazing conversation.

So they played a huge part and when I felt low I could always go home.

Gates: Being able always to go home, that's what home is or what it should be.

Merkerson: Yeah, yeah.

I could always go home.

Gates: Epatha and Michael come from tight-knit families.

But like so many African Americans, they have very limited knowledge of the lives of their ancestors.

Each told me that they knew little beyond their grandparents, and nothing at all about their roots back in slavery times.

All of that was about to change.

I started with Michael.

Both of Michael's parents were born and raised in tiny towns in Eastern Texas.

On his father's side, we were able to trace his ancestry back in the same area more than 150 years.

All the way to his third great- grandparents: James and Winnie Shankle, they were born decades before the Civil War... And likely lived much of their lives as slaves.

James Shankle and Winnie Brush.

Have you ever heard of these people?

Strahan: I've never heard those names in my life.

Gates: Have you thought about what life was like in slavery?

We're not talking about Kunta Kinte in roots.

We're talking about your own ancestors on your family tree.

Strahan: I've never really thought back like that.

Gates: Uh-huh.

Strahan: You know and I've been around enough to understand and understand from my father how it was for him growing up and how it was for my grandfather growing up, but to think back to my great-great-great grandparents and for them how it was.

I don't think I can.

I don't think I can comprehend that.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: It would be even hard to try to imagine because I don't wanna diminish what they went through by trying to, trying to put it in words.

Gates: There is no way to know for certain what Michael's enslaved ancestors experienced, but the records contain some clues.

The 1870 census reveals that his third great-grandparents were born in Kentucky and Tennessee... Which gives us a good idea of how, and why, they ended up in Texas.

We think they were brought there in what's called the Second Middle Passage, when an unprecedented cotton boom in the first half of the 19th century drew white settlers into the deep south... Where millions of acres of rich soil were yielding enormous profits... If you could get a hold of enough land and enough free labor from slaves.

They needed bodies to harvest all that cotton.

Strahan: Yeah.

Gates: Where were the slaves?

In the upper south.

Where your third great-grandparents were, and that's how they ended up in Texas, most likely because they were sold away, from their families, Michael.

Strahan: I mean think about that.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: You're there with people that you love, who love you, and that's your family, your blood.

The next thing you know, you're gone.

They probably have no idea where you went.

Gates: Right.

Strahan: And you'll never see them again.

I just, that's unfathomable.

I'm, I'm sweating over here because it, it, it makes you... I just, it makes me angry.

Gates: Oh, that, that's so.

Strahan: It makes me...yeah.

Gates: So painful to think about.

All to be at the service of this new cotton economy when cotton becomes king.

Strahan: Yeah, money.

Gates: It was all about the money.

Strahan: All about the money's right.

Gates: By the time Michael's ancestors arrived in Texas, slavery had been a profitable institution in North America for over three centuries... And it had given rise to a system that was relentlessly inhumane, stripping its victims of the most fundamental aspects of their identities, from their family ties.

To their very names.

This makes doing African American genealogy especially challenging, because it's exceedingly difficult to trace people whose names don't appear in records.

And when we tried to learn more about James and Winnie Shankle's families in Kentucky and Tennessee, we couldn't find any documents to guide us.

Their histories had been swallowed whole by slavery.

Fortunately, we picked up the trail with emancipation.

In the 1870 census, the very first census in which all of the freed slaves appear by name, we learned that Michael's ancestors had not only survived slavery they had miraculously begun to thrive.

Now, Michael, this is incredible.

Would you please read the transcribed section next to James' name?

Strahan: "Value, real estate, 200 dollars, value, personal estate, 125 dollars."

I got a smile on my face, man.

I mean now, now I'm like, okay, I'm proud.

We... We just wasn't accepting the situation was what it was.

We was trying to, we was trying to come up, as they say, so.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: Yeah.

Gates: Well, how in the world did people who were slaves?

Strahan: How did you come up with...?

Gates: In five years.

Strahan: I mean I know now we look at go "whoa!

", 1870, coming from a situation where you were the disenfranchised, where much wasn't expected of you, where you were just property.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: To be able to do that, I mean, I'm smiling, I'm happy.

Gates: And you should be.

Strahan: I'm happy.

Gates: And did you ever hear any stories about this?

We come from people, you know, we owned property?

Strahan: No.

Gates: It's such an extraordinary accomplishment, how do you think that story was lost in your family lore?

Strahan: I have no idea, but I'm gonna make sure I tell it to my kids.

Gates: Michael's ancestors were in a decided minority: in 1870, only about 5% of African American families in the south owned their own farms.

And their accomplishment is all the more impressive in light of the fact that it occurred against a backdrop of intense racial tension, as the former confederacy transitioned out of an economy based on slavery.

We showed Michael an editorial from 1867, to give him a sense of how some white Texans felt about the rising status of their Black neighbors.

Strahan: "To exalt the common African, with his thick skin, wooly head, his superstition, and silly notions to a state of perfect equality with the proud race of Anglo-Saxon blood is an attempt to place a libel upon the great purposes of God himself."

Whoa.

In other words, you not gonna be equal.

Gates: Man, that's cold.

Strahan: That's cold.

Gates: Mm.

Strahan: But just to think that you can just say that about another human being.

Gates: Yeah, and mean it!

Strahan: Yeah, and mean it, and I don't know, you're missing something in your heart.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: You're missing something, but... But at the same time, you're probably.

You grew up, that's what you were taught, and then you're able to express it in a paper.

Gates: And these are your neighbors, the neighbors of your third great-grandfather and grandmother.

Strahan: These are his neighbors.

Gates: So, these are the odds that he had to face.

Strahan: Wow.

Gates: The venom reflected in these words extended well beyond the printed page.

In the three years between 1865 and 1868, over 350 African Americans were murdered in Texas... Nevertheless during these same years, James and Winnie Shankle somehow managed to buy land and make a living farming... It's hard to imagine how they even survived.

But as it turns out, Michael's family did more than survive.

They launched an entire town!

Strahan: "Shankleville community, named for Jim and Winnie Shankle, known as first Newton County blacks to buy land and become local leaders after gaining freedom by emancipation.

In 1867, they began buying land, and with associate Steve McBride, eventually owned over 4,000 acres.

In their neighborhood were prosperous farms, churches, a cotton gin, grist mill, sawmills, schools, including McBride college, built by Steve McBride."

Holy!

Gates: Isn't that amazing?

Isn't that amazing?

Strahan: Whoa!

Gates: Did you know this?

Strahan: No.

I heard of Shankleville.

You know my parents are from the country, Shankleville.

I had no idea this tied into me or my family at all.

Gates: They built a family, they built a business, and as you can read, they built a community.

Strahan: Uh-huh.

That's cool, man.

Gates: That's cool, man.

Strahan: Wow.

Wow.

This, this is really one of the best things I've ever seen, one of the best things I've ever seen in my life, and I am going to Shankleville, I promise you that.

Gates: They reinvented themselves almost overnight.

They went from being a slave to a landowner.

That's amazing.

Strahan: And that, when you're building, like you say a prosperous farm, you're building churches, you're building a cotton gin, grist mill, saw mill, schools, you're building things that they weren't supposed to have.

Gates: Not at all.

Strahan: They're building businesses that they're not supposed to be able to own because how can a slave own this business, you know, not long after being free?

Gates: Yeah, it's amazing.

Strahan: And, and it's prideful.

Gates: Mm, yeah.

Strahan: The swagger I'm gonna have when I walk out of here is gonna be unlike anybody else.

Wow.

Gates: I'm happy for you, man.

Strahan: I'm happy too.

You have, you have made a happy man out of me.

Gates: Just like Michael, Epatha Merkerson has roots in the deep south.

Her mother was born in the tiny town of Maringouin, Louisiana, and Epatha believes that her ancestors have been in and around Maringouin for generations.

But beyond that, the shape of her family tree is a mystery.

Merkerson: I've always wanted to know where we came from.

And I have no idea other than, Maringouin.

And I remember when I was sixteen I got one of those little cassette recorders and my grandmother was visiting and I said to her, called her momma pearl.

I said talk to me about when you grew up and she was like no, turn that thing off.

You don't want to hear this.

And I said I do.

I want to know.

And she said it's painful.

You don't need to hear any of this.

Gates: Right.

Our researchers were able to discover some of what "Momma Pearl" withheld.

Census and marriage records took us back to pearl's mother, Epatha's great-grandmother, a woman named Easter Hawkins.

And indicated that her parents, Peter and Martha, were both born in Maryland... Likely in slavery... That's where the paper trail ran out.

We couldn't find records to take us further.

But then we noticed something in Epatha's DNA... And suddenly the wall erected by slavery began to tumble down... Merkerson: Oh, my goodness, okay.

Gates: Now, this is a chart showing a genetic network: people who share significant amounts of DNA with you and your mother.

Each of these people is related to you in some way.

Merkerson: Oh, my God.

Gates: So guess what all these people have in common?

Merkerson: What?

Gates: You and everybody on that page trace your ancestry to one person.

You read the name at the top.

Merkerson: Patrick Hawkins.

Gates: Does the name Hawkins ring a bell?

Merkerson: Oh, oh, back, back, to Easter.

Gates: Your great-grandmother Easter's maiden name: Hawkins.

Merkerson: Hawkins!

Wow.

Gates: So that means that Patrick Hawkins was more than likely one of your direct ancestors.

And since they share a surname, we imagined that he might somehow be connected to Easter your great-grandmother.

Isn't that incredible?

Merkerson: That's amazing.

Gates: Just through DNA.

Merkerson: That's amazing.

Gates: Now we faced a question: how was this man "Patrick Hawkins", born over two centuries ago, likely in Maryland, possibly related to Epatha?

To find out, our genetic genealogist, Cece Moore, began searching for a link.

Combing through DNA databases and comparing those results with records on the paper trail.

Through painstaking research, she uncovered a story unlike any we've ever encountered before.

It begins in the archives of Georgetown University... Where, in 1838, the jesuit priests who ran the school sold a group of slaves to two planters in Louisiana... The documentation of this sale was invaluable because it listed the slaves who were sold by name... And one name stood out immediately.

Merkerson: "Patrick, a man 35 years of age."

Gates: Now, you remember all your DNA cousins who descend from Patrick, that's Patrick Hawkins.

Merkerson: And that's how they got from Maryland to Louisiana.

Gates: He was sold by the jesuit leaders of Georgetown University to Louisiana planters in the year 1838.

Merkerson: Wow.

Okay.

It boggles the mind.

For Georgetown University?

A jesuit priest?

Gates: A jesuit priest selling 272 slaves.

Merkerson: Whoo!

Gates: Epatha was still uncertain how Patrick Hawkins was related to her, but that was about to change.

Georgetown's archives contained an inventory compiled in preparation for the sale... It lists the slaves that were to be sold according to where they worked, and it identifies their family members... Merkerson: "White marsh farm Isaac, about 65 years, Patrick, Isaac's second son, 35 years.

Letty, his wife.

Peter, his son, 5."

Gates: You know what you're looking at?

You're looking at the names of your family.

Merkerson: Wow.

I'm descended from these.

Gates: These are your people.

This is your family tree in that record of slaves.

Merkerson: Wow.

Gates: There's your third-great-grandfather Patrick Hawkins.

We know his wife's name Letty.

Letty is your third-great- grandmother, Epatha.

And their five year old son is your great-great- grandfather Peter.

Merkerson: They have names.

That's amazing.

Wow.

That's amazing.

They have names.

They're not just faceless people.

Gates: Right.

They're real people with names and they had children and grandchildren and they named them and they passed those names down.

Merkerson: Wow, this is pretty amazing.

Gates: All told, Epatha descends from at least nine slaves who were owned by the jesuits, including no less than three generations of her Hawkins family line.

For an African-American family, this was an astonishing discovery.

And as we dug deeper, we found something else, something that few of us are ever able to see, a description of how our enslaved ancestors were actually treated on the plantation... Merkerson: "Generally, the master provided no bedding except a blanket and an old straw sack, which was placed on two or three planks laid across some old wooden horses.

Some might think it harsh treatment to make the poor negroes sleep on the floor, yet, it is not hard to sleep thus, for custom softens things."

An old straw sack.

And these are men of the cloth?

Wow.

Gates: How are you feeling so far?

Merkerson: I'm saddened to, of course, you know, you always think about it but you never see it.

Gates: Never see it.

Merkerson: And when you can see it and then... It's a painful process but it's also joyful and so a part of the tears is joy that they were here and that whatever they went through they withstood it.

Gates: Yeah.

Merkerson: They lived through it and they lived through it long enough to get to me.

Gates: Yeah.

They endured.

Merkerson: They endured.

Gates: Yeah, so that you can thrive.

Merkerson: And this will mean so much to my mother as well.

You know, my mother, who's ninety-one, who's lived through... So much raising five children alone, all of them college educated because she comes from this.

Gates: Yeah.

Merkerson: It explains her in a way that I never could.

Amazing.

Gates: It's amazing.

Merkerson: Yeah.

Gates: We had already taken Michael Strahan back five generations on his father's side, and revealed that a town he'd known since childhood had actually been settled by his ancestors... An awe inspiring story that had somehow been lost within his family.

Now, turning to Michael's maternal roots, we once again confronted a loss of family history but of a very different kind.

Michael knew almost nothing about his mother's parents, and had heard only vague rumors about their roots.

Strahan: You know, I've heard that, we got some Indian in us and that was about it.

Gates: Uh-huh.

Strahan: You know, that was about all I knew.

I remember my, my grandmother with very fair skin.

My mom is, you know, with a lighter skin and straighter hair.

Gates: Yeah.

Uh-huh.

Strahan: And that's really all I knew, and being the youngest of six, I kinda got the tail end of my grandparents.

Some weren't alive when, when, from when I was born or from when I can remember.

Gates: So, you didn't, you weren't privy to those kind of stories?

Strahan: I wasn't privy, privy to those, no.

Gates: We started our search in the 1900 census for Jasper County, Texas.

Here we found Michael's great-great-grandmother, a woman named Harriet Mead.

Harriet was listed as a widow, working a farm, raising nine children on her own.

Can you imagine a single mom, nine kids, running a farm in Jim Crow Texas in 1900?

Strahan: Phew.

Gates: Talk about Black superheroes.

Strahan: Yeah.

Gates: I'm serious.

Strahan: Without a doubt.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: Well, it's something when you see somebody 10, 12, 14, 18, and farm labor.

Gates: Yeah, farm labor.

Strahan: At, at that age, you know?

Gates: Right, when they should've been in school.

Strahan: Yeah.

Gates: Right?

But no, they were out there in the fields.

Strahan: Yeah.

Gates: We wondered what had happened to Harriet's husband.

We searched marriage records across Texas, and beyond, and we came up empty... It seemed like we'd hit a dead end.

But when we turned to Michael's DNA, we saw something interesting.

After running his results through all available DNA databases, we noticed that Michael was part of a genetic network in which one particular surname repeated like a leitmotif: the name "bishop."

We'd encountered a similar situation with Epatha.

It meant that Michael had an ancestor named "bishop", even if we couldn't say exactly how they were related.

Have you ever heard that name mentioned in any family story, anything about a bishop ancestor?

Strahan: No, never.

Gates: Well, since your DNA was clearly telling us something, we investigated further.

Do you want to see what we found?

Strahan: Absolutely.

Gates: Well let's turn the page and find out.

Strahan: "Bishop, William A., age 48, boarder, widowed, occupation, farmer."

Gates: In 1900, a man named William Bishop lived just four households down the road from your great-great grandmother Harriet and her nine children.

Strahan: They were creepin'.

Gates: Sneaking and creepin', I believe the phrase is.

Strahan: Because I creep.

Yeah, okay, creepin', okay.

Gates: So, William and Harriett, brother, four households away.

Strahan: Okay.

Yeah.

Okay.

All right.

Gates: Isn't that cool?

Strahan: This is cool.

Gates: It now seemed highly likely that this man, William Bishop, was Michael's great-great-grandfather.

And when we saw that Michael shared DNA with multiple descendants of William's siblings we knew we were right.

We didn't have a marriage record to connect William and Harriet.

But as we pressed on we discovered a very good reason why the two couldn't possibly have wed.

Gates: I want to show you something else.

Please turn the page.

Michael, this is the same page we just saw, but this time we highlighted a different section.

Do you see that black arrow pointing at one of the columns next to William Bishop's name?

Strahan: Uh-huh.

Gates: That arrow is pointing to a column identifying an individual's race.

What letter is sitting by William's name?

Strahan: W. Gates: What's that stand for?

Strahan: White.

Gates: White.

"W" stands for "white."

Strahan: Hmm.

Gates: William Bishop was a white man.

Strahan: Explains a lot.

Gates: Like what?

Strahan: I guess, the color of the skin of my mother and her sisters, and I remember my grandmother, and even my grandfather was, was light-skinned, as well.

So, it's like that just answers that question.

Gates: Every African American we've ever tested has varying degrees of European ancestry.

And that's not a coincidence.

One of the most surprising facts of the history of American race relations is that the average African American is almost 25% European... This could be difficult to accept, because it generally reflects a dramatically unequal relationship between a white man and a Black woman.

And more often than not, it indicates rape.

But in Michael's case, William and Harriet appeared to have been involved in a way that was more complicated.

Gates: All told, Harriet and William had four children together.

Strahan: what?

Gates: Including your great-grandmother.

Strahan: Mm, mm, mm.

Gates: Their youngest child was born in 1896, and guess what his name was?

Strahan: Don't tell me Michael.

William, there we go.

Gates: William, absolutely.

It was William.

Harriett wanted everybody to know who his daddy was.

Strahan: Uh-huh.

Gates: Boy look like his daddy, William.

Strahan: Yeah.

Wow.

Gates: Isn't that amazing?

Strahan: Because that was, back then, that was a tough chance you're taking.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: Wow.

Gates: Michael and I were curious about the nature of Harriet and William's relationship... Unfortunately, we can only speculate.

If it was a loving bond, it would have been dangerous for them to acknowledge that publicly, because interracial marriage was illegal in Texas until 1967.

All we really know is that it was a long-term relationship... Beginning sometime before 1889, when their first child was conceived... And ending, we suspect, sometime around 1903, when Harriet, it seems, found someone else.

Gates: Harriet got married, and she married a Black man.

Strahan: Okay.

Gates: They had two children and stayed together until his death sometime in the 1920s.

Strahan: All right.

Gates: And William Bishop, your white ancestor, married his second wife, who was a white woman, about three years later, after.

Strahan: She got married.

Gates: After she got married, and they had at least two children together.

Isn't that amazing?

Strahan: Wow, just like tentacles.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: Everywhere.

Gates: Like tentacles.

Harriett said, "William, it's time to move on."

Strahan: Yeah.

Gates: "I found a man."

Strahan: Yeah, one that's legal, I can legally marry.

Gates: Yeah.

Strahan: Think about it like that.

Wow.

I would like to think that they didn't get married because they couldn't and not that they didn't want to.

Gates: Yeah.

Right.

Strahan: Yeah.

Gates: Yeah.

You know we weren't there, but the fact that she named her fourth child after the daddy.

Strahan: Yeah, that says a lot.

Gates: Does not suggest that she hated his guts, or you know.

Strahan: Yeah, yeah.

Gates: So it's completely different.

Strahan: Because she did, yeah.

Gates: It's one of the quirks in the history of American race relations.

There were all these fissures and cracks when things happened, that don't appear in the history books.

This is not like a Spike Lee movie when all the Black people get killed by the Klan.

Strahan: Yeah, but it, but it also goes to show that even back then, if someone, I don't know if it was love or whatever it may've been, but if somebody loved someone or somebody was attracted to someone that race didn't matter.

Gates: No.

Right.

Strahan: You know it was human nature.

Gates: Love, love across a color line.

Strahan: Whatever it was.

Gates: Yeah, even in a climate of intense racial hatred.

Strahan: Yeah, exactly.

Gates: Now that we knew William Bishop was Michael's great-great-grandfather, we could trace his roots as well... And because William was white, there were many more documents to draw upon.

We discovered that his parents, Allen and Dorcas Bishop, moved to jasper county Texas in the late 1840s...only a few years after Texas became a state!

So, you have deep Texan roots on the white side of your family tree as well.

Strahan: pretty amazing.

Gates: That's pretty amazing, and guess what?

On the left is a picture of what's called the oxen yoke, a part of the harness attached to the actual oxcart that the Bishops traveled in, in the mid-1800s.

That is your family's oxen yoke.

It's been kept in the family for over 170 years.

Strahan: Are you serious?

Gates: I'm serious.

Strahan: Wow.

"The Bishops to Jasper county from Georgia in 1849."

Gates: These people were hardcore pioneers.

Strahan: Taking a chance.

Gates: Yeah.

Now, do you feel a connection?

This is your blood.

These are as your ancestors as validly as any of the black people that we have seen.

Strahan: Oh yeah.

I mean, yeah, I mean I definitely feel the connection, and it's an unusual connection, taking a turn I didn't expect.

Gates: I wish that there was a time machine, right, and we can take this back, and I could say, Allen and Dorcas, I'm from the future, and your descendant is famous.

Strahan: Could you imagine that?

Gates: Is famous, and he's behind the curtain.

Okay, you ready?

I take it off and they go ahh!

Strahan: I'm here.

Now, when you said your great-great-grandmother, well, I was like could you imagine he did not know his son was gonna have a half-Black child.

He had no idea about that.

Oh man.

I mean when you imagine the shock they would have, boom, but you know it's a little shocking to me.

Gates: Yeah!

Strahan: But you know I think it's, it's important to know exactly where you come from.

Gates: Sure.

Strahan: Now, I don't have all these, well, I heard, or I think.

Gates: No.

Strahan: Like, now I know, I wanna know.

Gates: What do you think these people would've made of you?

Strahan: Hopefully they would be proud, you know?

Hopefully they would be proud and they would see the trait that made them into what they are and were into me.

Gates: Uh-huh.

Strahan: They would see those traits in me.

And I'm proud.

I mean I'm really proud, and it makes me definitely think more about my American history, in a sense that I feel like i, I have one now.

Gates: Uh-huh.

Strahan: I really understand it.

Gates: Does seeing all this change your sense of yourself?

Strahan: Yeah, absolutely.

I'm gonna walk a little taller, stand a little taller, you know what, sway a little more when I walk.

And I just, it makes me feel more complete.

When you know where you come from then it just makes you feel good about.

Now I know that I belong, and I don't feel like I'm just kind of floating on this planet, not knowing, and just going day-to-day.

Now I know I'm here because, I come from this line of people who have paved the way for me to be in this situation, and this is a paving of the way that's just in your DNA that you don't recognize that has you where you are now, and you look back at the mentality of your parents, the mentality of yourself, and you see the mentality of the people you come from, and you realize those things can and do get passed along.

Gates: We had already shown Epatha Merkerson how her maternal ancestors, the Hawkins family, arrived in Louisiana... Revealing that they had been sold into the deep south by jesuit leaders in 1838... But there was still more to the story... And to appreciate it, we needed to step back in time, back to the 1630s, when jesuit priests arrived in Maryland, fleeing religious persecution in England.

To support themselves and their mission, which came to include Georgetown University, the jesuits began operating tobacco farms.

By 1838, they had six Maryland plantations, covering almost 12,000 acres.

And to run them, they needed labor.

And you might be able to guess what kind of laborers they used.

Merkerson: My family.

Wow.

That's extraordinary.

So they left England to be free from persecution to practice religion and then they persecute folks when they get here?

Gates: That's it exactly.

You got it.

Merkerson: Yeah, yeah.

Gates: By 1838, the jesuits owned close to 300 slaves including three generations of your family, your bloodline.

Merkerson: Wow.

This is like a trip.

Gates: The jesuit plantations operated for more than a century... But in the early 1800s, Maryland's tobacco market declined, and the jesuits struggled to keep up.

As debts mounted, the very survival of their prized university was at stake.

The documentation of this process still exists in the archives of Georgetown, allowing us a unique glimpse into the mindset of the men who owned Epatha's ancestors, and the mechanism by which her family was forever altered.

Merkerson: "Were the servants sold, a thousand could be made from the land besides supporting the missionaries.

The sale of the servants should bring at least 16,000 which would bring 1,000 interest."

Gates: In 1833, the priests then, began considering selling their slaves, referred to there as "servants", in order to raise funds.

When the sale was finally approved in 1836 by the catholic church in Rome, the university found a catholic buyer in Louisiana willing to pay $115,000 for the slaves.

Which converts to between $3.3 and $7.5 million today.

It's difficult to know the precise value but what is agreed upon by scholars is that the university owes its very survival, its existence today to the sale of Black human beings.

Including people whose bloodline goes directly from 1838 to... Merkerson: Me.

Gates: S. Epatha Merkerson.

Incredible.

Merkerson: This is quite extraordinary.

A university, a religious organization.

Okay.

Wow.

I really don't know what to say that you can air.

I just feel like anybody I know should be able to go to Georgetown, you know what I'm saying?

They should be able to go to Georgetown for free.

Gates: I agree.

Merkerson: That's how I feel.

And maybe I'll just go there and take some classes.

Gates: Epatha's words may very well prove prophetic... Georgetown university is still wrestling with the implications of the sale... An independent group called the "Georgetown memory project" has calculated that the 272 slaves sold in 1838 have at least 6000 living descendants today.

Initially, a university official tried to deny this claiming that the slaves succumbed to fever upon arriving in Louisiana.

But the truth eventually came out.

Gates: In 2016, the president of Georgetown, John Degioia made an official apology and held an open conversation on Georgetown's history.

Merkerson: All of this is going on.

Gates: Yeah.

In 2016.

After students demonstrated.

Isn't that amazing?

Merkerson: And my sister is like an avid newspaper reader so she's probably read about this.

Gates: Well, when you get home you just Google Georgetown and slaves and you'll see it.

Merkerson: I'm going to have to.

Gates: It was huge.

Merkerson: That's crazy.

And so this story of my family is still alive.

Gates: um-hum.

I'm going to show you one more thing.

Merkerson: Okay.

Gates: Would you please turn the page?

Merkerson: All right.

Gates: Now, you see that?

Any idea what that is?

Merkerson: Isaac Hawkins Hall.

Gates: The university decided to rename one of their buildings as part of a larger effort to address its history.

So they renamed that building Isaac Hawkins Hall in memory of your fourth great-grandfather.

Merkerson: Get out of here.

Gates: You know why?

Because Isaac's was the first name on that 1838 sale document.

Of all those people it started with your fourth great-grandfather.

Merkerson: Oh, my gosh.

Look at that.

Amazing.

Spirit of Georgetown Residential Academy.

Isaac Hawkins Hall.

I love this.

Gates: How amazing is that?

And you were directly descended from this guy.

You have DNA from this man.

He's your great-great- great-great-grandfather.

Merkerson: That's deep.

That's really deep.

Gates: It's deep.

You couldn't have made this up.

Merkerson: No, I'm telling you.

I'm telling you.

Wow... Gates: Our research was now complete for Epatha Merkerson and Michael Strahan... It was time to present them with their family trees... These are all of the ancestors that we found, showing entire branches filled with names they'd never heard before... Gates: You carry DNA from all these people.

Merkerson: All the little parts of me!

Gates: For Michael, one branch was especially surprising.

Through his white ancestry, we discovered that his roots trace back to several of the Kings of England.

And to a man who once ruled almost all of Europe.

You're descended from Charlemagne.

Strahan: Royalty, I'm a King, y'all.

Gates: Charlemagne is your 39th great-grandfather.

Strahan: what?

What?

Oh, my goodness.

Gates: Who would've thunk it, as we used to say?

These are your blood ancestors.

Strahan: Unreal.

I don't know what I expected when I walked in here and when I agreed to do this, but this is beyond anything I ever.

Beyond anything I ever would've expected.

I know more now about my family, which, which blows me away, and I'm so thankful for this, because I found I come from, okay, this, the King of England and... But also a King in their own rights, the Shankles.

Gates: The Shankles.

Strahan: in Texas, came from nothing to create something.

Gates: They did as much as your white ancestors.

You know?

Strahan: Yeah.

Amazing.

Gates: This marked the end of my time with Michael and Epatha... But for Epatha, the journey wasn't over... Merkerson: So, did you know about all of this?

Gates: A few weeks after we met, Epatha traveled to Louisiana... To join a Reunion of the descendants of the enslaved women and men who were sold and scattered in 1838.

Woman: We are here today to continue this journey of learning about our history.

Woman: We are heirs of their strength, grit and their love.

Merkerson: And how did you decide to gather all the information?

It's just always been coming?

Did your family talk about it?

Woman: My grandfather said we were from the north.

Man: Alright, smile.

Gates: Miraculously, more than 200 people, many of them Epatha's newfound cousins.

Merkerson: It's a little overwhelming.

Gates: Gathered here, united by the fate that their ancestors shared, bound together in the memory of long lost friends and family members to embrace for the very first time.

Merkerson: Glad to have you here!

Woman: So good to be here.

Family.

Merkerson: Yeah.

Excellent.

Woman: Thank you!

Gates: That's the end of our search for the ancestors of S. Epatha Merkerson and Michael Strahan.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of Finding Your Roots.

Ryan: How did you get that?

Narrator: Next time on Finding Your Roots, Senator Marco Rubio.

Rubio: That's amazing, I mean I didn't even believe any of this stuff existed.

Narrator: Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard.

Gabbard: This is really cool.

Narrator: And former congressman, Paul Ryan.

Ryan: Nobody in my entire family knows any of this stuff.

Narrator: Unexpected ancestors.

Rubio: Oh wow, he's a lawyer.

Narrator: Who paved the way... Gates: They risked everything.

Ryan: Everything.

Narrator: For three politicians.

Gates Jr: How's that make you feel?

Gabbard: Honored.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S5 Ep5 | 30s | Dr Gates traces the family history of S. Epatha Merkerson and Michael Strahan. (30s)

Michael Strahan | Related to Royalty

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep5 | 1m 24s | Dr. Gates traces the family history of Michael Strahan. (1m 24s)

S. Epatha Merkerson | Ancestors Who Endured

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep5 | 2m 47s | Dr. Gates traces the family history of S. Epatha Merkerson. (2m 47s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: