Funk music and its connection to Detroit, Michigan Poet Laureate Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd

Season 53 Episode 13 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

The evolution and influence of funk music and Michigan Poet Laureate Melba Joyce Boyd.

“American Black Journal” host Stephen Henderson talks with Satori Shakoor, who was a member of the Brides of Funkenstein, about the documentary “WE WANT THE FUNK!” and Detroit’s connection to funk music. Plus, Henderson sits down with Michigan Poet Laureate Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd to discuss her new position, what it entails and what influences her poetry. She also reads her poem “Stage Black.”

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

American Black Journal is a local public television program presented by Detroit PBS

Funk music and its connection to Detroit, Michigan Poet Laureate Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd

Season 53 Episode 13 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

“American Black Journal” host Stephen Henderson talks with Satori Shakoor, who was a member of the Brides of Funkenstein, about the documentary “WE WANT THE FUNK!” and Detroit’s connection to funk music. Plus, Henderson sits down with Michigan Poet Laureate Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd to discuss her new position, what it entails and what influences her poetry. She also reads her poem “Stage Black.”

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Black Journal

American Black Journal is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Just ahead on "American Black Journal," a new PBS documentary examines the history and influence of funk music, we'll have a preview, and we'll talk about the Detroit connection to funk.

Plus, we'll discuss the power of poetry with Michigan's new poet laureate.

Stay where you are, "American Black Journal" starts right now.

- [Announcer] From Delta faucets to Behr paint, Masco Corporation is proud to deliver products that enhance the way consumers all over the world experience and enjoy their living spaces.

Masco, serving Michigan communities since 1929.

Support also provided by the Cynthia & Edsel Ford Fund for Journalism at Detroit PBS.

- [Announcer] DTE Foundation is a proud sponsor of Detroit PBS.

Among the state's largest foundations committed to Michigan-focused giving, we support organizations that are doing exceptional work in our state.

Learn more DTEFoundation.com.

- [Announcer] Also brought to you by Nissan Foundation, and viewers like you, thank you.

(gentle upbeat music) - Welcome to "American Black Journal."

I'm Stephen Henderson, your host.

A new documentary, titled "We Want the Funk," debuts on "Independent Lens" here on PBS on April 8th at 9:00 PM.

Now, the film, by director Stanley Nelson, chronicles the history and influence of funk music and features legends such as James Brown, George Clinton, and David Bowie.

It also examines the relationship between funk music and the political and racial dynamics in 1970s America.

Here's a preview.

- Two, three, and one.

- James Brown.

- George Clinton.

- Sly and the Family Stone.

- Funk is something that takes you over.

- A history that goes back to the spiritual.

- Funk got the whole world dancing.

You certainly couldn't contain it culturally, and you couldn't contain it geographically, either.

- Funk is the DNA for hip hop.

♪ Da, da, da, da, da, da - Just lose yourself in it, and that was the thing.

- Detroit PBS has teamed up with "Indie Lens Pop-Up" and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History to hold a free panel discussion and screening of "We Want the Funk" on April 3rd at the museum.

Joining me now is the moderator for that event, Satori Shakoor, who hosts "Detroit Performs," right here on PBS.

And she is also a member of The Brides of Funkenstein, who were the backup vocalists for George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic, of course, one of the really pivotal funk bands.

Welcome back to "American Black Journal," Satori.

- Thank you for having me.

- I have to say, I didn't know this about you.

- Oh, you didn't?

- I didn't.

- Okay, all right.

- That's a really, really great detail about your very, very interesting and diverse life.

All right, so let's talk first about this documentary and the idea of chronicling this part of music history.

I think of funk as having had too short a life really in American music.

It gets kind of corrupted or curtailed, I guess, by lots of other things.

- Yes.

- But tell us about that period.

There's a lot going on, not just in music, but in America, while funk is the thing.

- Yeah, funk did have a short lifespan in its time, but there has been so much sampling- - Yeah.

Right.

- Of the music.

And George encouraged that sampling.

So when I watched "Straight Outta Compton," it opens up with them playing the funk, you know?

And having that live on through the music.

And, of course, "Atomic Dog-" - Yeah.

Right.

- Is in every- - Is everything.

- Everything.

So who knew, you know?

Who knew at the time.

- Yeah.

Talk about what your role was as a Bride of Funkenstein backup vocalist and the things that were propelling, I guess, that music.

It's all so on the edge, especially Parliament-Funkadelic and some of the other bands.

But, musically, it is pushing bounds that I think are really important still today.

- Yeah, well, my role as a Bride of Funkenstein was, I was a recording artist, singer on tour.

So we did double duty, we did our own album, "Never Buy Texas From a Cowboy," "Funk or Walk," and then we also sang backup for Parliament-Funkadelic.

So I guess our role was to be the female equal of the men.

It was so many men and us three girls.

And we provided that edge, that women.

But what I loved about it, while we weren't The Supremes, not that I didn't love The Supremes, but I'm saying we were more hard-edged.

The costumes, the vocals.

We tried to have a routine when we played the Pontiac Silverdome.

But when you walk out in front of 80,000 people, that energy hits you, and every routine you might've rehearsed flies out.

So we just did our thing.

- Yeah.

- At the time, I didn't really understand our role.

I just wanted to sing.

That's all I wanted to do from knee-high, "I wanna sing."

And so that's what I was doing.

- That's what you did, yeah.

- I didn't know we were making history.

I didn't know that history would land me at your table and in your presence talking about this documentary.

- Yes, you were just doing the work.

- Yeah, doing the work.

- Yeah.

- Yeah, it was hard work too.

- I'm sure it was.

Tell us what it was like to work with George Clinton, who is, of course, a pioneer in so many different ways in music.

- It was absolutely creatively satisfying, because George encouraged, quote, "mistakes."

So he would say, "Sing this," and people would get on the mic and they'd mess up.

But they'd mess up on purpose and George would go, "Mm, keep it."

So when you hear, "Ma-ma-ma-do, baby," with Bootsy, wasn't supposed to be there.

A lot of things that find itself to be iconic phrases were not really supposed to be there.

So I love that mistakes were a creative opportunity.

- Yeah.

- We spent long hours in the studio and we would clap down tracks that were 15 minutes long, that meant we would clap down tracks six times for six tracks.

- Wow.

- I remember "Atomic Dog."

I remember "Not Just Knee Deep."

We were totally, you know, that was all...

When George ordered a pizza, we knew we were gonna be there all night.

And, of course, touring is very, very hard.

- Yeah.

- We would go hit one town, and then get back on the bus and go to another town.

Sometimes we wouldn't get a hotel for three days, 'cause we were sleeping on the bus.

And when the guys would go out there and say, "What's the name of this town?"

it's because we really didn't know.

We had to look at the license plates to figure out where we were.

- Where you were.

- It was hard work, but it was work that a young person with dreams and excitement could handle, you know?

- Yeah.

Yeah.

- Yeah.

- Let's talk about the event on April 3rd, what will people discover when they get there?

- You're gonna see the film, which I've seen, which you're gonna be very satisfied.

Things you didn't know.

Obviously, that's what film brings you, things you didn't know.

But then you're gonna hear from panelists such as Cheryl James, who was their stage manager, road manager, was there from almost the beginning.

You're gonna hear from David Lee Chong, who wrote "Atomic Dog" and who was on tour.

And you're gonna hear from Kevin Saunderson, a techno guy who was very, very much influenced by the funk.

And you'll hear some of my stories and experiences.

But it will be very entertaining.

- You mentioned Kevin Saunderson and the influence on techno.

The influence on techno and hip hop I think is the legacy that funk has.

But, you know, funk finds its roots in Detroit music and Black music, of course.

But the influence of Motown in particular, I feel like, on the explosion of funk is really interesting.

How much of that were you thinking about while doing it?

- Well, I'm a Detroit girl.

- Yeah.

Right.

- And Motown, you know, influenced me, but it also influenced George.

You'll hear in George's stories, matter of fact, when he was on my show at The Secret Society over at the DIA, he talks about trying to fit into the Motown mold of routines and looking the part in suits, and they just couldn't conform.

But they were very much influenced by that music, I think they just took it to another level.

Maybe they dropped some acid.

I think they talk about dropping some acid or some drug, and they went way left and they liked it.

- Yeah.

Yeah.

- Yeah.

- I mean, I also think of bands like Sly and the Family Stone and the influence there.

I mean, there's kind of a direct line to funk from bands like that.

- Oh yeah.

- Which come out of the sixties and the Motown era, but they weren't as conformist as some of those bands were.

- No, when I watched the Sly documentary, I was very surprised at the diversity of bands that he produced.

- That he produced, right.

- And the writing that he afforded them.

And George was very much influenced by Sly.

Matter of fact, when I was on the road, Sly Stone came on the road with us, along with Philippe Wynne- - Really?

- And Jessica Cleaves.

- Wow.

- Sly was producing our third album before our contract was lost at Atlantic Records.

But I think George was very much influenced by the politics of the time.

- Yeah.

- The political environment, the Black Power.

And so when I came on in 1978, we were doing the One Nation Tour.

So we wore the fatigues, and we were very much about one nation and all people coming together, which was one of Sly's mantras and one of his missives.

- Yeah, yeah.

- Mhmm.

- All right, well, Satori Shakoor, it's always great to talk with you.

- You too.

- It is also great to learn about this detail of, again, your very storied life.

Thanks for being here on "American Black Journal."

- Thank you for having me.

- Yeah.

Up next, we are gonna meet the new Michigan poet laureate.

But, first, let's take a look at a clip from a 1978 conversation between "Detroit Black Journal" host Ron Scott and the king of funk and soul music himself, James Brown.

- A lot of people today don't have the kind of philosophy that you do, a lot of young people.

I know you do a lot for young people, they don't know what it is to struggle, it seems.

A lot of people get things very easy.

When you talk to a group of young people, what do you say to 'em?

- That's one of the things I clarified right away.

I let them know that they don't know, and try to, you know, impress upon 'em the fact that what they are talking about is, they're a long ways from it, but they are getting some of the delayed actions that are still there.

The fragments are still there, which are coming together and making a whole molecule, and, based on that, came back to the same thing.

But it's going back a little bit more sophisticated this time.

- Talking about going back to the same thing, a lot of people think of you, James Brown, as only an entertainer.

When I say only an entertainer, they see you on stage and, you know, think about "Licking Stick," "Cold Sweat," or anything.

I can go back, "Night Train," so on.

But the point is, you, I would say, are a total human being.

You were telling me about the title of a new show that you're doing- - Called "James Brown: The World of Love."

We gonna start shooting it from LA pretty soon.

- [Ron] And this is your production, you control everything on it?

- Yes.

Control I must have of myself, either that or I can't give you James Brown.

- [Ron] Why is that so important?

- So important, because if I've gotta speak somebody else's tongue, it wouldn't be me, and then I would be doing my people who believe in me an injustice, you know?

People who follow James Brown throughout the years- - Do you think that's important for other people in addition to you?

I mean, let's say, for instance, for people in general, for a number of people who may be, or have found themselves in a similar situation like you?

- It's important for every artist, regardless of whether it's music, or sports, or what have you, they should be able to project themself.

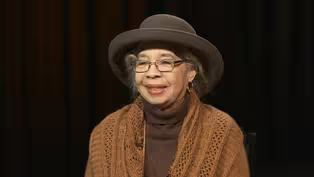

- April is National Poetry Month, and Michigan has a new poet laureate to help promote the importance of poetry throughout our state.

Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd is an award-winning author and a retired professor of African American Studies at Wayne State University.

She will be the third person to serve as the state's poet laureate.

I'm really pleased to have Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd as our guest today.

Welcome to "American Black Journal."

- Thank you for having me, Stephen.

- Yeah, it's always wonderful to see you.

This is a great occasion to have a conversation with you as the third person to be our poet laureate.

Let's start by talking about what a poet laureate is and what that person does.

- Oh, well, let me put it like this, my job is poetry.

- Yeah.

Right.

And to get people to love poetry.

- Exactly, but the point being to obviously do poetry readings, workshop, you know, with students at all age levels, to go into libraries in the state and do readings for the communities, and to be available, I think, and excited about the opportunity to promote poetry, especially in a time where there's less reading and probably less reflecting.

They're already seeing that poetry will encourage and also develop, hopefully, in our young people.

- Yeah, I mean, you've been doing this for a long time, in addition to teaching at Wayne in the African American Studies Department.

I wonder what you make of the place that poetry has in our culture right now.

It does seem more difficult to get people engaged, I think, with poetry than maybe at other periods.

But I wonder what it looks like from your chair.

- Well, actually, I find that, well, poetry is very important to culture for sure.

It is probably the most artistic of all of the, shall we say, verbal forms of artistic expression.

But like the late Naomi Long Madgett said, "It's probably the most underappreciated of all the art forms."

- Yeah.

- But I find, at the same time, that people enjoy it, they respond to it, because it is generally pretty intense.

At least the poetry I write is pretty intense.

- Yeah.

- But I think it's important to encourage, not just necessarily that people become poets, but that they view poetry as a resource to stimulate both creative and critical thinking about the world we live in and have lived in.

- That intensity that you mentioned, talk about where that comes from and what you intend for the reader to draw from that intensity.

- Well, there's a passion, hopefully, when people are writing poetry.

I tend to be motivated by people that I know, people that I have encountered, both, you know, in real life and also in literature.

I'm very much influenced by other American poets, particularly African American poets have had a very strong impact on me.

The intensity comes from the form itself that you've got to say a lot more in fewer words- - In a very little space.

- Than if you were, you know, writing in prose.

And I do write literary history, and essays, and so forth.

But the intensity I think is also the delivery.

It's not just the imagery, it's also the sound, very much like music.

You were talking about George Clinton and the funk movement.

And the better, you know, musicians or vocalists, their lyrics are actually poetry.

- Poetry.

Sure, yeah.

I mean, I also find that quality writing and storytelling in other forms also seems to borrow from poetry in terms of structure, rhythm, sound.

I think most writers pay attention to those things when they're writing.

And they're getting it, though, from poetry, whether they might, you know, acknowledge that or not.

- Well, certainly even when you're writing prose, you want it to have a rhythmic structure so that you, in effect, capture your audience and engage them in a manner sometimes subconsciously using rhyme, slant rhyme, in order to emphasize a point.

Even when I'm writing prose, if the rhythm's not right, I'm like, "Oh, no, you know, you gotta edit this.

This is not working."

Yes, but I also feel that, as a poet, I'm very much influenced by other art forms.

Certainly music, and as well as visual arts.

I've written poems in response to artists' work, you know.

And, in particular, I did a response to a painting, an abstract painting that hangs in the DIA, which was entitled "Maple Red," by Ed Clark, and the curator there asked me if I would write something.

And I've done some other responses in terms of how an artist responds, you know, to abstraction, visual abstraction.

And also though I'm very much interested in history, and what is the connection, what's going on in the art that is related, you know, to different forms of our reality.

So it's, for me, important to be actively engaged in the broader artistic community, because it keeps you sharp, it keeps you growing.

And also when you're writing about art, you can't let it fall flat, right?

So it's, you know, it's very important, I think, to do that, and to have that as a part of your keeping, you know, your tool sharpened.

- Right.

Right, right.

- Otherwise, it can be too much of just your voice, and that's important.

- So I've got you here.

I would be remiss if I didn't ask you to read some of your work for us.

- Okay, well, let me see what I have.

I tend to write a lot about Detroit, and also, like I said, about people that I know.

And so I think what I wanna do today is to maybe read a poem that I wrote years ago for Ron Milner, who was a very important playwright- - Playwright, yeah.

- You know, here in the city.

And I wrote this poem, we had a memorial program for him.

He was a very good friend of mine, and I was a part of that cultural community that he had already, you know, developed largely.

That was Ron Milner, and Dudley Randall, who was my mentor, Naomi Long Madgett.

So Detroit was a really great place during that time to develop.

- Yeah, I'm sure, yeah.

- And this poem is entitled "Stage Black," and the opening quote is from Ron himself.

"Death is just the gateway to everlasting life.

And change is the gateway to reorder, rebirth, renewal, to re-life."

That's Ron Milner.

- Mhmm.

- "I first met you in a play peering inside the mind of the character Linda lamenting with Smokey Robinson's romantic croon, 'More love, more love,' a scene scripted to a Motown tune.

You could not stay away from this city of automobiles, of sweet, smoked barbecue jazz, of fried chicken, rhythm and blues, of tree-lined streets reaching as deep as Black Bottom, and as far away as Paradise Valley.

As a sorcerer of words, your plays reversed the language of hate, dispelled the illusions of a cursed cast in 1943 at the barricades when savage rumors were thrown off the Belle Isle Bridge.

Or in '67, on 12th Street, when we rebelled against the brutality of blind police.

Or, in 1972, when we exposed homicidal undercover cops.

You reanimate our chorus, you insert song into monologues, direct checkmates pivoting on jazz sets, salvaging joy diminished in the throes of turmoil, ciphered through the vice of the republic's manifold.

Like the deaf dance of a butterfly, your writing maps muted beauty like pain reading, grieving, flesh, defining the gray, creasing the lines, connecting our past.

But like a breeze off the Detroit River, your passing is rebirth, reliving, filling this air, this city as you reorder this script, rearrange this scene, determine this set, stage black."

- Wow.

Wow, there's so much in that.

There's so many touchstones for our city and our culture in that work.

It's always great to have you here.

Thank you so much.

- Thank you for having me.

- And congratulations on being the poet laureate.

- Thank you.

- That's gonna do it for us this week.

You can find out more about our guests at AmericanBlackJournal.org, and you can connect with us anytime on social media.

Take care, and we'll see you next time.

(gentle upbeat music) - [Announcer] From Delta faucets to Behr paint, Masco Corporation is proud to deliver products that enhance the way consumers all over the world experience and enjoy their living spaces.

Masco, serving Michigan communities since 1929.

Support also provided by the Cynthia & Edsel Ford Fund for Journalism at Detroit PBS.

- [Announcer] DTE Foundation is a proud sponsor of Detroit PBS.

Among the state's largest foundations committed to Michigan-focused giving, we support organizations that are doing exceptional work in our state.

Learn more DTEFoundation.com.

- [Announcer] Also brought to you by Nissan Foundation, and viewers like you, thank you.

(gentle music)

Detroit native Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd named Michigan’s third-ever poet laureate

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S53 Ep13 | 11m 14s | Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd discusses being named the new Michigan Poet Laureate. (11m 14s)

‘WE WANT THE FUNK!’ documentary explores the evolution of funk music and its connection to Detroit

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S53 Ep13 | 10m 13s | A new documentary explores the history and influence of funk music and its connection to Detroit. (10m 13s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

American Black Journal is a local public television program presented by Detroit PBS