Giant Robot: Asian Pop Culture and Beyond

Season 13 Episode 5 | 56m 28sVideo has Closed Captions

Giant Robot was a bimonthly magazine that profoundly affected Asian American pop culture.

Giant Robot was a bimonthly magazine that created an appetite for Asian and Asian American pop culture, exploring Sawtelle Boulevard as a Japanese American enclave. Founded in 1994 and driven by Eric Nakamura and Martin Wong, it resulted in a legacy of Asian American artists that achieved worldwide recognition such as David Choe and James Jean.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Artbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

Giant Robot: Asian Pop Culture and Beyond

Season 13 Episode 5 | 56m 28sVideo has Closed Captions

Giant Robot was a bimonthly magazine that created an appetite for Asian and Asian American pop culture, exploring Sawtelle Boulevard as a Japanese American enclave. Founded in 1994 and driven by Eric Nakamura and Martin Wong, it resulted in a legacy of Asian American artists that achieved worldwide recognition such as David Choe and James Jean.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Artbound

Artbound is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMan: In the nineties, being Japanese American wasn't cool, but it was cool to me.

So I published "Giant Robot" to be different.

Is that how you want to start it?

Singer: ♪ Kick me the in face Yeah, hit me with that attitude ♪ Man two: We were a bunch of misfits, skaters, punkers, artists, and I was "Oh, finally, there's something for me."

Man 3: Like, being the outsiders kind of makes for more interesting work.

Margaret Cho: Hey!

Let's really celebrate alternative Asian Americans.

Announcer: This program was made possible in part by: the Los Angeles County Department of Arts & Culture; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Frieda Berlinski Foundation; and the National Endowment for the Arts, on the web at arts.gov.

Man: I'm going to Anime Expo.

It's as massive an event as possible here in downtown.

It's crazy.

100,000 I think they say, maybe more.

For a while, I swear that people would say, "There's no Asian American culture."

I heard that a lot, and I was just like, "What?"

There's definitely Asian American culture, and it's huge now, but I think in the 1990s--95 or something--I was told there was no such thing as Asian American culture, and that was, like, a radical change that I was interested in pursuing.

My earliest memory of Asian culture or Japanese culture would be me probably watching monster movies as a little kid.

[Godzilla roars] "Godzilla."

I think "Gamera" was part of it, too, and then there's "Giant Robot."

"Jainto Robo," I guess is what you would call it legit in Japan.

That's kind of where the title comes from, from "Giant Robot."

In the eighties or nineties, being Japanese American wasn't cool, but it was cool to me.

You know, like, going to elementary school, I would take a Japanese lunch, and people would be astounded at how odd everything was.

They didn't understand what a rice ball was or Japanese pickles for that matter.

They didn't get it, but I got it, and it was an enjoyable lunch.

Better than peanut butter and jelly.

Then later on, I was into, you know, punk rock.

I wasn't an outsider in punk rock.

Let's put it that way.

I think everyone's an outsider, so in that way, everyone's equal.

Man: You know, punk rock is where it all began really.

Growing up in Southern California, like a lot of new wave and bigger punk bands, like British ones, you know, like of course the Clash and Damned and Siouxsie and all that.

Look at this Germs 7-inch.

I like 7-inches because they're not as expensive as records, so I can be more frivolous.

I met Eric because I would go to shows at UCLA, I would go to Al's Bar, I'd go to Jabberjaw.

There weren't a lot of Asian people going to these shows, right, and, like, we were both Asian dudes with long hair because this is, like, nineties, right, and either you become friends or enemies, and we became friends.

Eric: It was like this really similar vision of everything and maybe similar upbringing and similar interests.

Martin: Eric--he contributed photos for, like, music-related zines... and I was writing for, um, you know, "Flipside."

Eric: In the nineties, we had only magazines or zines to learn about what was coming up.

For the most part, there was not a magazine that I would consume that I would think, "This was perfect for me."

Martin: And he said, "Yeah.

I want to make a zine."

I said, "Me, too!"

And then I swear, like, probably a month later, it was done.

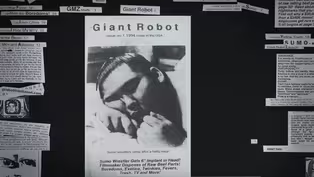

Eric: That photo--I think it was just stolen from a book.

Sorry, photographer, whoever shot that photo.

Uh, just took it from a book.

Martin: But look at that pillow-like cheek.

Eric: Yep.

Started "Giant Robot."

Ha!

Out of like--I think starting "Giant Robot" all came out of just seeing all this other media that I didn't fit with and maybe I didn't want to write for, I couldn't write for, and then seeing punk rock zines that looked like they were made instantly.

There is a place for this intersection of punk rock, Asian, and Asian American things to exist, and I think I was just like, "This is what I want to do.

That's the vision."

Martin: I think the first one had Eric's Jon Moritsugu article because he was an assistant underground filmmaker.

Our friend Lynn wrote about yellow fever, I think.

I wrote Hong Kong movie, like, soundtrack reviews.

Eric: The idea of making a magazine, it's been in my life for a long time.

I think I've wanted to publish things since I was little.

I just had to get out there, that's all.

A zine just has no real distribution or circulation.

The life of a zine might only have 50 copies, and that's it.

No.

The mass market out there, a zine is pure garbage.

It's not even something to look at, but if you're a zine consumer, yeah, you'd understand the value.

I was gonna keep going until it either worked or really crashed.

Issue two.

Martin was Hello Kitty.

He's in that costume.

Martin: I got a job being Hello Kitty.

Why not?

I overheard they needed someone, so I'm like, "Oh.

This could be a cool article, you know?"

It's a zine.

It's participatory.

Back then, there was a lack of pride, I think, in Asian stuff.

It was, like, super uncool to be Asian, I think, yet, you know, the coolest movies are coming out of Hong Kong.

There's so many rad-- I don't know, just everything, right?

Japanese robot toys.

You're flying the flag.

Eric: Issue 3.

Oh, my gosh!

It's large sized.

Martin: This is where it says, "A magazine for you," for the first time.

There's all this different stuff that we put together, and maybe film dorks were into one thing.

There's, like, people who are into comics, and there's people who are into music, but to have all of those plus food in one thing was a little different, I think.

Eric: This is an OG copy because the pagination was wrong, and there's a plain white page to draw your own [bleep] in if you want to.

Oops.

Margaret: The aesthetic was very much more geeky, more nerdy but at the same time very feminist, very punk rock, very much proud of our communities.

I was a heavy consumer of Hong Kong cinema, anime, manga, all these things that weren't being covered in any sort of media.

Woman: I think now everything Asian is trendy, but back then, they weren't.

Asian culture was something that was very far away, right?

Asian American culture was kind of tossed aside, as well, and I think that even though those of were living Asian American culture, that wasn't being represented, and those stories weren't being told.

In 1987, there was this "Time" magazine cover "The Asian-American Whiz Kids."

You know, to show us as perfect and assimilationist.

This respectability politics, right?

You have to be perfect in order to be seen as a legitimate group.

Man: I remember this magazine.

My mom brought this into the room, and she goes, "See?

You need to be like this," and I wasn't one of these kids.

You know, my mom tried to force me to play violin, piano, all that stuff.

I remember for piano practice I recorded one session on tape, and then the subsequent practices, I would just play that tape back on a little hi-fi and sit under the piano and read comic books while my mom was in the kitchen thinking I was actually practicing piano.

And so when "Giant Robot" came around, it was, you know, this punk music, movies, art, all these things that I was interested in.

I was like, "Oh, finally, there's something for me."

Like, without ever even meeting them ever before, I understood these people, I knew what they were about, and so I just wanted to be part of it.

Martin: We had a food review on Asian liquor, and I did a sidebar on drunken boxing.

Dan Wu--he sends a letter, like, from Oregon when he was still an architecture student saying, "Hey.

I could teach you."

You know, he went from being a reader to being someone who's becoming an actor and filmmaker and a "Giant Robot" writer.

Ha ha!

Daniel: I tried to write for every issue I could, but I became the kind of Hong Kong correspondent.

I was really trying to get people over here to understand the culture over there because it's very distinctly different.

Martin: To us, like, Hong Kong movies were just like going off at the time, right?

John Woo was on fire.

Eric: That was still kind of unknown in America, right?

It was still a little bit like the best kept secret.

Martin: It was a big deal, right, when "Crazy Rich Asians" came out here or "Shang-Chi."

Like, those were such a big deal to, like, most Asian Americans, but to us, it's like, "Dude, we've been watching, like, Chow Yun-Fat and Jet Li and Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung, Michelle Yeoh and Gong Li and-- like, forever!"

If you just watch more than Hollywood, there's as lot out there.

Daniel: The things I saw on screen was Long Duck Dong from "Sixteen Candles."

Like, that [bleep] sucks, right, seeing that, growing up with that, and trying to, like, break out of that image.

And so that's why I gravitated toward Hong Kong movies because I saw Chow Yun-Fat and I saw Jet Li, and they were cool guys doing cool stuff onscreen and not these nerdy guys doing nerdy stuff onscreen, right?

Martin: Oh.

The Tony Leung cover.

Eric: Yeah.

The Tony Leung one, that was cool.

Martin: And this was actually scanned of a Hong Kong movie poster I had at home.

Eric: I don't remember how we got Tony Leung, but I recorded it.

It was a long phone call.

Martin: Did you have to use, like, a phone card or something?

Eric: I don't remember.

Nancy: "Giant Robot" being able to invoke these icons gave a perspective that was necessary for Asian Americans.

Like, "Look.

Asians can be anything."

Eric: Maggie Cheung.

She cut her own hair for that interview.

She looks great.

She was ahead of her time with this haircut.

Martin: Yeah.

My daughter has that haircut now.

We talked a lot about music I remember.

Growing up in England and, like, being into the Specials and Madness and stuff.

Margaret: I think what our generation of Asian outcasts can really tell people is that we really belong and that this magazine was really about the art of belonging.

Katherine: Margaret, do you know why I encouraged your brother to become a cardiologist?

Margaret: No.

Katherine: Because I always knew that one day you'd give me a heart attack.

What are you wearing?!

Margaret: When I was doing "All-American Girl," my TV show, my Asianness was such a problem because I was either too Asian or not Asian enough or too fat, which to me, it's like, "Yeah, but I'm playing myself, so how can I be too fat to be myself?"

It's a very, uh, skewed view of reality, and, like, you know, it's really indicative of the way that race was viewed back then in the nineties.

Oh.

Well, I've got news for you, Mom.

I'm American, Eric is American, even Stuart is American.

So it was a really cool thing to be able to write in the magazine, to talk in the magazine, to do whatever.

With "Giant Robot," you got a lot more of an area to express yourself.

Oh.

This article was really good.

It was when I got to be in "Transpacific."

"Transpacific" was another Asian magazine, and it was so indicative of, like, "We want Asian women to look a certain way."

Oh.

Let me tell you about the photo session.

It was super weird.

It was like a satin sheet on a desk.

It was so weird and creepy, and they didn't even use any of the photos, but, yeah, I love that I got to write about my experiences.

And, yes, in this issue, he skates Manzanar, which I think is one of the most iconic-- iconic things about "Giant Robot."

Martin: The "Skate Manzanar" issue happened because we were really close to deadline, we had pages to fill.

My family and I, we would go on road trips to Mammoth often, and I knew that Manzanar was there, but I'd never gone out, you know, to visit, to stop.

So we went, like, on a Saturday morning, just Eric and me.

It was his brilliant idea to bring skateboards and get those big wheels on them because we thought we were gonna be out in the desert, right?

Eric: Manzanar was a Japanese American internee camp.

I think wanted to reclaim--reclaim a historical, evil place, right, an awful place and really show what's there.

And then all of a sudden, you find the reservoir, and it's like, "Whoa.

There's a reservoir that's like this?"

Martin: Yeah.

We wound up skateboarding in those banks, and that was, like, a really powerful, cool moment, you know, where we could take something that was very serious, very messed up and flip it.

Eric: I think it's taking back what is kind of this ugly period of history.

My dad--he was interned for, what, 3 years at Poston.

I think he was 10 years old at the time, but he really didn't tell me too many stories about being in internment camp.

I've heard it from everyone across the board that those stories are mostly repressed and not really told.

This is our way.

How does "Giant Robot" look at it?

And that's how "Giant Robot" looks at it.

Woman: Some people were really angry about it.

They thought it was defacing this historical site, which I kind of agree, but on the other hand, the site was an atrocity anyway.

I thought it was really important that a new generation of not only Japanese Americans but Asian Americans were really thinking about this place and how to make meaning out of it.

You know, this is where we were, this is where we lived, and this should not happen again.

This it.

"Skate or Die."

That sums it all up.

The whole history of Asian Americans has been an activist history, but nobody knows that.

Everybody just knows the stereotype, the model minority, you know, the wedge.

People don't know the whole history of activism.

Martin: The "Yellow Power" article, I think it was really important for us.

We always say that it's the most bootlegged article we ever did because, like, all these Asian AM studies would photocopy it and stick it in their readers.

Eric: If I remember, I think it's 28 pages worth of interviews and articles about Asian American activists from different eras.

Yuri Kochiyama is often looked at as, like, the quintessential Asian American activist, right?

I think that's kind of groundbreaking for a pop culture magazine.

People looking for pop culture, and all of a sudden, now we're giving them something really serious that's a little bit underground, right?

Man: There's something about the Asian American experience that's very, like, keep your head down.

You got to keep apologizing for [bleep], you know, and there was something very unapologetic about "Giant Robot."

I'm like, "What?

These guys have no respect just like me."

Like, when I do graffiti, there's anger in there.

It's [bleep] you.

When I talk sarcastically, there's anger in my sarcasm, and, like, that was "Giant Robot," right?

Martin: Dave Choe--he was looking for jobs, and he loved "Giant Robot," and I said, "Well, you know, we have this article about Martin Yan, the chef, and we don't have art for it."

No one ever says, "Yeah, I'll do it," and then actually does it.

That does not happen at all ever.

David: That was the first time my work had ever been published, and then I got hooked on it.

I would just be like, "What do you guys need?"

I can draw.

That's my special superpower that I can bring to the table, but I could do a lot of other things.

Martin: We'd find people like Dave Choe, who weren't known as writers, but they would write the most amazing things for "Giant Robot."

Eric: Because they weren't writers.

David: I went to the Congo when I was 19.

The craziest story of my life, and he's like, "You should write it."

I'm like, "What does a African story have to do about 'Giant Robot'?"

He's like, "You're Asian American, so that's what makes it Asian American."

I'm like, "Oh, OK." It was very empowering.

Margaret: "Giant Robot" was so important to understanding our identity as Asian Americans and alternative Asian Americans.

It shows that we can be our own beings and not necessarily follow a model minority myth or archetypes that are set out for us.

Woman: I picked up an issue of "Giant Robot."

Jenny Shimizu, the model who was famous for the CK One ads, was on the cover.

At the time, you never saw Asian women on the cover of magazines, you never saw Asian people on the cover of magazines.

I just remember flipping through it, and Jenny was just saying things that you would have never read anywhere else.

I was like, "This is the kind of interview that I want to read, and this is the kind of interview that I want to do."

If you look at the breadth of the pieces that I wrote for them, they range from lactose intolerance to, like, straight profiles of Wong Kar-Wai and Maggie Cheung.

I mean, you have to remember that I wrote for "Giant Robot" for free, so when you do stuff for free, it's just because you love it.

I always had an agenda, which was to put as many cool Asian, Asian American people in these pages.

I'll always remember Wong Kar-Wai.

At one point, I said to him, "You make Asians look cool, more so than they are in American films," and he said, "Asians are cool."

It was just deadpan, and it's like, "Oh, yeah."

Martin: Yeah.

Of course there's Asian Americans that did awesome, rad stuff, but they're overlooked usually.

If you're just relying on mainstream media, they're not gonna show the Asian person, right?

When they show early punk rock, they don't show brown people like Alice Bag and the Zeros.

They don't show Dianne from the Alley Cats, but they're all there, so for us to shine a light on Asian people, you know, in music or movies that we think are cool, it was really important to us.

Man: I never really aspired to be, like, a Asian producer or Asian hip-hop guy.

I aspired to be a hip-hop guy or a hip-hop producer, and that's a very big distinction because I wasn't trying to do something to be the best Asian.

I was trying to be the best period.

David: That was kind of like the Keyser Soze moment for me because everything's like "an Asian American magazine."

I don't even like saying that, you know, Asian American.

It's so long.

I just want to be the best artist.

So you have this guy Eric, who is Asian American, and then when you go back and you look through all the issues, it's not "I'm putting this guy in just because he's Asian.

It's because he's the best."

Eric: Wow.

Is this the Yeah Yeah Yeahs?

Martin: It is.

I interviewed them on their first... Eric: Wow!

She looks so cool.

Martin: their first shows.

Claudine: Eric was the arbiter of coolness for "Giant Robot," and Eric always had a very clear point of view of, like, what was cool, what was in, what was out.

There was no gray area about it.

It was like you just know.

It's like you know.

If I pitched a story that even had, like, a whiff of not cool, he would just, like, crush it.

Eric: There's a lot of things to say no to because it's not good, right?

Woman: Yeah.

I would say there was a culture of cool factor, musical taste, and-- Dan: I was a snob.

I was a hater, not a snob.

I'm still a hater.

Miwa: We had strong opinions.

Eric: This was an important article for me.

It's completely an eff you-- Martin: To all the other... Eric: It's an eff you.

Martin: or the other 2 or 3 Asian American magazines out there, right?

Yeah.

So it's not like were the only magazine that focused on Asian American stuff, but we were the only one that wrote about stuff that mattered to us.

They feel like they have to write about stuff that's Asian and happening, and there's this sitcom coming out with this actor in it, and you should all watch it, but we're like, "Man, that's kind of a bad show.

Is that cool?

Is that really great for Asians and Asian Americans or whatever?

You know, it's not really that cool."

Eric: "The magazines are cheap."

Martin: "The magazines are weak."

Eric: "The magazines are paranoid."

That hurts.

"The magazines are weak."

[Bleep].

This drew the line in the sand.

It's like, "We are not like them.

[Bleep] you.

Stay over there."

Martin: And they were like-- we knew that people that did it.

Like, we would run into them here and there.

Man: They certainly poked fun at us, you know, I think, and for good reason.

I mean, nobody-- nobody loves to the be in the middle, right?

"A.

Magazine," we focused on this idea that we were going to trace the emerging outlines of what it meant to be Asian in America, and then here we were covering Asian Americans who were decidedly somehow exempted from that middle by and large, and we found ourselves playing to the middle, as well.

"Giant Robot" at least had teeth.

That was so important for Asian American independent media.

Even though we were nominally competitors, at least for space on newsstands, every single one of us were out there just, you know, trying to make sure every issue would allow us to publish another issue.

David: There's a fantasy of how things are made until--not today because the Internet shows you everything, but, you know, how they make the sausage.

You know, you're like, "Magazine," and I'm thinking of, like, an office with, like, hundreds of people, but it was just, like, 3 or 4 people doing everything.

Woman: So the office space at "Giant Robot" was basically the garage at Eric's house.

It was very messy.

Ha ha ha!

Eric: yeah, yeah.

Martin: It is.

Eric: We are at the old office, but this is the back room.

Martin: And then the garage was converted into an office, but for a while, most of my life was in this building.

During production, work all day, and then Wendy and Prior would show up after their day jobs, and we'd be here till 11:00 or midnight or whatever.

Eric-- he was MacGyvering the graphic design in the beginning, like, starting with glue sticks and tape and then figuring out, you know, graphic design programs, but eventually, starting with issue 18, he's like, "Man, we just need a real graphic designer."

Wendy: So I was helping them with their web site, right, and then I would see them working on the magazine, and I was like, "You know, I can make it a little easier for you.

Maybe I could help you out, and then you'd have more time to--to do your thing, you know."

Like, for example, this was a article where Martin Wong meets Martin Wong, right, who is an artist.

I just felt like, "Well, I don't know if I can really read this that well," although I do love the energy, you know?

So that's one thing that I wanted to try to rectify.

I think I saw early on that this content needs to be able to be read.

The word count was so high, we had to, like, squeeze in a lot of content into 88 pages.

I felt like I had this huge ball of string I had to, like, wrangle and get under control.

You, like, try to clean it up, make it organized, and then you kind of start to loosen up.

You see, like, the content your get in and how you can make it sing a little more.

Eric: Right away, I just thought, "Oh, man.

Good designs, good mind for this."

Things like this, like, I don't think without Wendy we would have done this, like, pull one frame from a comic.

Look how big the dots are.

Who does this?

Like, the gutter of an article.

Like, you read it, and it kind of like zigzags over here instead of just going straight down, and it still has black and white pages.

We're not even close to being full color yet, but you kind of forget that there's even black and white because the design's good.

Wendy: They had strong opinions, but they also always let people do their thing if they had trust in them.

Eric: Our magazine's really dude-like.

You know, we're two dudes making a magazine, but I think her design turned it into something really clean that would attract everybody.

Martin: It didn't look as ziney.

You know, it looked more like a magazine.

Eric: The art thing coincided perfectly with Wendy's arrival.

Martin: Kind of, huh?

Eric: Because I think it totally-- Martin: Would have been wasted otherwise.

Ha ha ha!

Eric: Yeah, right.

I think it totally is tailormade for it.

I liked art, but it was new to me.

I didn't know any art history really.

I think I approached it from a pop culture angle, and that's what made it really fun and amazing.

[Indistinct chatter] Murakami's exhibition, I saw it as a phenomenon, a change, you know, a word--a cataclysm in pop culture.

Some of these are classics, classic pieces.

I've seen this before.

Murakami: OK. Yeah, yeah.

Eric: Yeah?

It's the same one from... Murakami: I think so.

Eric: "Blum and Poe"?

Murakami: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Eric: "Blum and Poe," right?

Murakami: Yeah.

Eric: Aw.

This is great, man.

Here.

I got to take a picture of you here, man.

That's beautiful.

Martin: I remember going to the Pacific Design Center.

That was around 2000, and it was just, like--I'd never seen anything like it.

Eric: It was a show for outsiders.

Nobody really knew about it.

People were covering it for the first time, and I was on equal footing... so I'll write about it.

I'll even put it on the cover of a magazine.

Let's see everyone else do that.

Daniel: I think they did that Murakami cover with the eyes-- they broke that cover before any of the artworld knew about Murakami.

In that way, I felt it was even more legitimized because it was from people that really liked art.

Martin: It kind of changed everything.

The same way we were there for, like, when Hong Kong movies were hot.

Starting with Nara, going to Murakami, and then going to Chiho.

It just went on and on.

It's like, "Let's keep going, but superflat's gone.

Now what, you know?"

And Barry McGee was a friend.

Eric: Barry McGee, though, is still, like, just legendary.

He brings, like, contemporary-style graffiti into the museums, I think.

I'm a Barry McGee fan.

I think he's--again, him, too.

One of the founding fathers to my cultural, like, identity, right?

Barry McGee's totally part of it.

Martin: Then you have him and Shogo back to back in the magazine, right?

So good.

And then, you know, we were friends with Adrian Tomine from going to comic-cons.

Seonna Hong was just someone that was in our universe, also.

Geoff McFeteridge out of skateboarding.

Man: I can tell you there was a period of time where it felt like pretty normal that there was, like, a new culture magazine that, like, was part of, like, a world that I was adjacent to.

This, like, sort of collision of artmaking and, like, product design or collaboration.

When things sort of started, it was, like, messier.

It wasn't seen as art, but there was, like, real art stuff, like, happening.

David: There was a lot of bias, discrimination, I don't know what you want to say, of "If you're this, then stay in your lane, bro," and so Eric was unapologetic, and he's like, "I don't care.

I just like art."

Man: This was definitely completely different than any art magazine in the sense that, you know, when Eric spoke or Martin spoke in their writings it was never pompous or pretentious.

It was always accessible, relatable, and used a lot of the nomenclature of identity and culture.

Martin: Looking back, Eric and I were just sharing the stuff we like, but there's an importance to that, and having that voice, making that voice, making that space was something that wasn't happening then.

Eric: I think people would see the magazine, and maybe there would be an article about a figure toy or something like that, and they would ask, "Oh.

Where can I get one of those?"

And, you know, it was one of those things where I would direct them to places that would have it, and then I was thinking, "Well, if we're gonna write about this and actually know the makers and get really into it, maybe I should stock this stuff and then sell it myself."

You know, there's a lot of people that want to give advice, and I think the advice I was getting was no brick and mortar.

Become the next Amazon, so of course, open a brick and mortar.

I think most thought it was the wrong thing to do.

Back then, it was bizarre.

You know, it was something totally knew, different.

I was, you know, mixing artistic things with Japanese pop culture goods and just things in America I thought were amazing.

So you mesh it all together, and you had "Giant Robot."

I put Sawtelle Japantown on a bunch of the caps.

I think it's because that's just a part of the identity of the store is Sawtelle Japantown, being here, and it's not just "Giant Robot," but it promotes the area.

Renee: So Sawtelle was a traditionally Japanese American neighborhood.

I remember--I used to live in Sawtelle, so I would see Eric.

Like, I just thought he was another sansei kid like me.

He kind of took that whole Japanese American vibe but then expanded it to what people were sort of discovering.

Eric: I remember the first day or one of the first days I was thinking, "Wow.

There's people coming in and buying things and actually spending money," and then it was kind of like, "OK.

This is gonna work."

Martin: So after he opened the store, he said, "Hey.

I think you can stop looking for a job," because I was in between gigs, and I started working for "Giant Robot."

Like, every day, I'd go to the office and work on the magazine into the night, right?

It was awesome.

Eric: The magazine, in the nineties it was definitely dirt poor.

Put it this way.

There's no taxes being paid and no money being made.

I think having a store that actually, yeah, would make money, it definitely brought in dollars to make the magazine happen.

Martin: Eric--he likes to grow things and take it as far as they can go, right, and we were interviewing all these artists and indie artists and people visiting the town, so he actually, um, opened GR2 across the street.

Eric: "Giant Robot" was creating a culture in a way, right, a new lifestyle, a way that you could think or live or be like, and that was something unique about the store.

I'd like to say the same with the art gallery.

This is a very abnormal exhibition.

It's called "Rakugaki," which in Japanese means doodle.

Some of it can look unfinished, some of it can be literally just an idea from an sketchbook, but that's what makes the show kind of successful.

I knew a lot of artists who had nowhere to show their work, and then some of them have told me stories how they took a portfolio into a big gallery, and they were just, like, told to leave.

I'm just, like, thinking, "Oh.

There's a need."

The first show was David Choe.

David Choe's show was a great proof of concept.

David: So I remember my career was kind of blowing up, and pretty established galleries wanted to show my art, and I was like [bleep] you.

I had a lot of loyalty, still do to "Giant Robot" and Eric, so my first art show ever in Los Angeles was at GR2, a comic book store/t-shirt shop.

Eric: This room was superpacked.

There were so many people outside on the street.

When I saw that, I was like, "Oh, wow."

They were hanging out all night.

Geoff: I feel like they made this impact.

Like, you'd just end up at those openings, and there was all kinds of people that were coming out of that world.

Like, the question would be, like, how many people had their--like, showed their first piece of art, like, hung their first piece of art on the wall at the "Giant Robot" gallery.

David: I think he has a lot of pride in, like, discovering a lot, and he has.

He's given a lot of young artists their first show, and a lot of us have gone on to, like, huge careers.

You know, James Jean was pretty much known as a illustrator, but he showed James Jean's art first.

Man: When I was living in New York, in Brooklyn, at the time, artists couldn't focus on making merchandise or design objects.

You had to, you know, do one thing or the other.

You know, I had really varied interests.

GR2, yeah, it was very exciting because you could finally see that a lot of young artists had a venue that just didn't exist before, but actually, Eric rejected me.

He rejected my portfolio, and so that kind of makes me, like, a double outsider.

Eventually, I became friends with Eric, and gradually of course I became more successful, and then it came to a point where it was like, "OK. Eric has to put me on the cover of the magazine."

It's really difficult to be an artist.

It's a very precarious life, and having people like Eric or "Giant Robot" is essential to that ecosystem.

[Indistinct chatter] Woman: This gallery--I knew it from the magazine, and I'm from South Carolina.

It's a lot of, like, beach portraits and, like, things like that, but I do a lot of kind of creepy horror art.

So when I met Eric for the first time and he saw my art and he invited me to a group show, I was like beyond excited, so I've loved this gallery for a really long time.

Eric: I like telling kids what they can do, and if it's in defiance of their parents, even better, but then I got to massage it to their parents and say, um, "What your kid's doing could work, and, you know, they don't have to be a doctor, lawyer, they don't have to do things that you think are financially successful.

They can do it their way and still be financially successful, and they can be happy," and I think I'm into doing that.

My parents didn't understand "Giant Robot" either.

They didn't understand this at all, and they even said one day, "We love what this is.

We can't help you."

If you want to build stuff, you know, you just keep going.

How big did we get?

We had a store in San Francisco, there was a store in New York, in Manhattan.

Then there was a Silver Lake store on the other side of town.

So it was, like, almost like creating a national circuit as if it's like a league or something.

I would do an art show with an artist here.

I could interview them in them in the magazine, and they could have a solo show in New York, have one in San Francisco.

We had this whole, like, little machine going on.

Clement: That's where Eric's entrepreneurialship makes him stand out.

He's willing to take risks, and I think he would probably say, you know, what he is doing is very punk rock.

Right now, I'm surrounded by some of the remnants of the many creations from the minds of Eric Nakamura, Davide Choe, James Jean, and just all the crew of "Giant Robot" magazine.

You know, when I first met Eric, he definitely seemed like an entrepreneur.

He was always looking for opportunities, and so when I broached him with this idea of an exhibition, he was all open, and within a matter of two months, we were able to curate the first "Giant Robot" Biennale.

We were kind of nervous about what was happening.

We didn't know how the public would respond to this or everything, but little did we know that Eric's network was wide and vast and deep.

David: "Giant Robot" to celebrate all the work, everything they've done.

You know, pretty prestigious spot at the Japanese Museum.

I'm like, "I'm not Japanese, you know," and Japanese and Koreans have their thing, and it's like just for me my first, like, real showing in a museum, not at a gallery, is at the Japanese National America Museum.

That's kind of weird, but, like, [bleep] it, you know?

Clement: The day of we're getting flooded with phone calls about where to park, how to get there, how much is the admission.

By the end of the evening, we had more than 2,300, more than the museum had in any other previous opening.

David: We're still Asian in a way where you do all this [bleep] and you make money and people like you and all that, but there's still things like being accepted by the institution.

To have a show at a museum--I saw his parents.

They were very proud of him.

You know, my parents came.

They were very proud of me.

Eric: I think doing something at the Japanese American National Museum, there's, like, a lot of history here, and to be part of that history is to me amazing.

My grandma's name on the wall of this building somewhere.

Although this place is called the Japanese American National Museum, you can have an exhibition and have, like, this great mix of people.

I mean, I'm amazed at, like, the diversity, and that's kind of nice.

Clement: I think for Eric when he became a curator it was a natural transition because what he was doing with the magazine was bringing together a bunch of talents and tastes and ideas and presenting them in a cohesive package called "Giant Robot."

This exhibition really is just a transformation of those concepts into now a physical, 3-dimensional space.

Martin: Definitely we're cruising at this point, like, where there's just so much happening.

Like, we've got all these friends doing rad stuff, and then more people are just coming out of the woodwork, right, that we're discovering or meeting, and it's just so easy to put together 88 pages of really intense, awesome stuff.

Eric: There's a point where I can remember all the covers, like, in order, and then there's a point where I just--there's too many.

Martin: It's a blur Eric: Because we started doing 6 issues a year.

I'm like, "What?

What is this?"

Martin: We must have been out of our minds.

Eric: Yeah.

Seriously.

Martin: Like Michael Jordan with the flu.

Eric: Oh.

We were that good?

Martin: 60 points.

Yeah.

It's like a conveyor belt.

You don't stop, and maybe that's why it couldn't go forever because we never stopped to think about that or go, "Oh, my God.

Things are digital," or, "Oh, my God.

Paper's too expensive."

Like, we just kept going.

Like, it's what we did, you know?

Geoff: You could say it's, like, the worst time to make a magazine, but it was actually the last time to make a magazine, so what are you gonna do?

Eric: I know that the magazine in about 2008 started to fall apart a little bit.

Circulation was going down, printing costing the same.

Advertising dollars were falling.

Everything was falling at the same time.

Barack Obama: The severity of this recession will cause more job loss, more foreclosures, and more pain before it ends.

Eric: There was that economic crash or whatever you want to call it.

That whole subprime mortgage issue happened, and it fell out into retail.

Like, a lot of stores closed at that time.

Closing the stores was a interesting project actually.

There was a point where I had no choice.

It was do this, or everyone loses their job there at the magazine.

Once that period started, I was the one who flew to New York and closed it.

I flew to San Francisco and actually did the hard work.

I dumped garbage in a park at a park Dumpster illegally.

I think everybody was on borrowed time frankly.

If I look back, it was probably a year too late.

Daniel: Hey.

How's it going?

My name's Daniel Wu, and I've been asked to talk to you about what "Giant Robot" means to me.

Basically, "Giant Robot" means the world to me.

Martin: We had fundraising, drives, you know, and we tried to get people to donate, knowing that we needed help, knowing that advertising was drying up and costs were going up, but I don't think you ever really expect it to happen.

Eric: I think when you mix it all together--you know, rise of video blogs, rise of video-- what do you call it--YouTubers, the rise of all these things at the same time just all hit around 2009 and 2010.

This online shift, how everything was moving online and moving digital.

That's exactly what, you know, we should be doing, but they're doing it and doing it well and getting views, more views than our magazine would.

Hi.

I'm Eric Nakamura.

Martin: And I'm Martin Wong.

Eric: And we're doing a video podcast of issue number 64.

Martin: And this is our first video podcast, so give us a break.

Eric: Yeah.

Thanks.

So, uh, "Giant Robot"...

The hardest part ever to admit is that I think just "Giant Robot" just got uncool after a while.

The subject matter was for people who are 40 years old.

20-year-olds don't want to read what 40-year-old Asian Americans are writing about or saying.

If it's true, as the publisher and owner, that's business.

Martin: I actually was in Europe for the first time for my cousin's wedding, and Eric's like, "Hey, man.

This is really important.

You got to call," and he said that "Yeah, you know, things are really bad for this next issue," and, yeah, the last issue came out with fewer pages.

Instead of being 88, might have been like, 68 or 72.

I can't remember.

Eric: Oh, it's heartbreaking.

All that was heartbreaking.

I remember the day.

I remember how it went.

I was just like, "This is it.

Like, we're done, like, now.

It's done now," but it wasn't planned.

It was almost like leaving a party without saying good-bye type of thing.

Martin: In the end, like, we weren't that big.

We knew that we were, like, a big fish in a small pond.

We were never more than a zine.

We never saw ourselves as the voice of Asian America... and maybe that's why we only lasted 16 years.

Eric: I don't think magazines are supposed to last forever, and "Giant Robot" didn't have to last forever.

I don't think so.

"Giant Robot" lasted as long as it's supposed to be.

The voice is definitely indelible.

It's Martin and I. it's our voices together in this magazine, and that's not meant to last forever.

Martin: It was really hard when the magazine ran its course because that was my identity, right?

Like, I was just pouring my guts out about stuff I loved with people that I really cared for, and I wasn't gonna work at the store because that's not my thing.

I'm a--I made magazines, but I was a husband and a dad, and I had those things to do.

It's funny because, um, Wendy and I we met doing "Giant Robot."

Wendy was the graphic designer, I was the editor.

You know, we got married when the magazine was going on.

We had Eloise when the magazine was still being printed, and then when the magazine ran its course, pretty much she, like, became my new readership-- ha ha--for "Giant Robot" stuff.

Eloise: Yeah.

Like, ever since I was little, my parents have taken me to punk shows, like, daytime matinees at Amoeba.

Wherever we go, whenever we go to shows, Daddy always bumps into someone from "Giant Robot."

It's like, "Hey!

Martin Wong!"

Martin: Like, even though she hasn't read all the issues, you know, she's totally familiar with the culture, but maybe most importantly, though, she's just able to express herself and do her thing and not take [bleep] and just do what she loves and try to make a difference, and that's what counts, right?

Mila de Garza: A little while before we went into lockdown, a boy in my class came up to me and said that his dad told him to stay away from Chinese people.

After I told him that I was Chinese, he backed away from me.

Eloise and I wrote this song based on that experience.

Eloise: So this is about him and all the other racist, sexist boys in this world!

[Playing "Racist, Sexist Boy"] Nancy: The Linda Lindas, it's like the aspirations of "Giant Robot" are now manifested.

Eloise: ♪ Racist, sexist boy You are a racist ♪ Nancy: Seeing these young girls of color call out racism and misogyny in a time when Asian American women are being targeted in a punk sensibility, knowing that they are part of the legacy of "Giant Robot" was very, very empowering.

Eloise: ♪ Racist, sexist boy ♪ Margaret: We were all working separately to put together this common goal of creating Asian American culture in a way that was inspiring for a new generation.

Daniel: We were not trying to impress our Asian parents or the white community or the white gaze or trying to fit into mainstream culture.

We had our community and our own culture, and we created it ourselves, and Martin and Eric did that for us.

Martin: I never made a plan like, "Oh, we're gonna do this for 16 years."

It's like, "Oh.

Let's make a zine," and then it just kept going, you know, and it kept growing, and it kept happening, and I think if you read them you can kind of see us grow, and you can see, like, culture change.

Eric: Anime was a niche thing, so this is way bigger than anyone could ever expect it to be.

It's for everybody.

Ha ha!

It's so crowded.

There's an argument to be said that "Giant Robot" helped Asian American culture, which I can't say we're 100% responsible, and here it is 28 years later from "Giant Robot" magazine's beginning to now.

There's definitely Asian American culture.

It's huge.

Claudine: I don't think I ever anticipated that the Asian American or Asian pop culture were ever going to get as big as they have, and so to see, like BTS and Blackpink topping the charts is mind-blowing to me that, like, it has happened.

[Cheering and applause] Karen O.: Here we were, 3 generations onstage.

[Cheering and applause] Let me know when you're ready.

Renee: There's no one way to be Asian American or talk about our experience to express our experience, and it kind of leads us to imagine what our future is going to look like.

David: So "Giant Robot" wasn't doing that good.

I don't know the exact details, but they almost went out of business a few times, you know, and had to shutter everything, so I went to Eric, and I said, "Give me all your money, and I'll double it for you."

So he gave me, like, 30, 40 grand, something like that, and I went to Vegas, I doubled his money or close to it, like, almost, and it was like, "Hey.

You want to write a story about it?"

You know, it's like everything became the magazine, you know?

It was my life, you know?

Announcer: This program was made possible in part by: the Los Angeles County Department of Arts & Culture; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Frieda Berlinski Foundation; and the National Endowment for the Arts, on the web at arts.gov.

Giant Robot: Asian Pop Culture and Beyond (Preview)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S13 Ep5 | 30s | Giant Robot was a bimonthly magazine that profoundly affected Asian American pop culture. (30s)

Reflecting on Giant Robot's Earliest Zine Issues

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S13 Ep5 | 3m 46s | Giant Robot founders Eric Nakamura and Martin Wong reflect on the magazine’s first issues. (3m 46s)

Why Giant Robot Skateboarded at Manzanar

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S13 Ep5 | 2m 45s | For Eric Nakamura, skateboarding Manzanar was a way to recaim a site's dark history. (2m 45s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by:

Artbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal