'Jazz from Detroit’ film, ‘Regeneration’ Black films exhibit

Season 52 Episode 15 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

‘The Best of the Best: Jazz from Detroit,” film, “Regeneration” Black cinema exhibit.

A local documentary, “The Best of the Best: Jazz from Detroit,” explores Detroit’s jazz legacy and impact on the world. Host Stephen Henderson talks with the film’s co-producer and writer. Plus, the Detroit Institute of Arts’ “Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971" exhibit highlights the trailblazing Black filmmakers and actors from the early days of cinema through the Civil Rights Movement.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

American Black Journal is a local public television program presented by Detroit PBS

'Jazz from Detroit’ film, ‘Regeneration’ Black films exhibit

Season 52 Episode 15 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

A local documentary, “The Best of the Best: Jazz from Detroit,” explores Detroit’s jazz legacy and impact on the world. Host Stephen Henderson talks with the film’s co-producer and writer. Plus, the Detroit Institute of Arts’ “Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971" exhibit highlights the trailblazing Black filmmakers and actors from the early days of cinema through the Civil Rights Movement.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Black Journal

American Black Journal is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Coming up on "American Black Journal", a new documentary about Detroit's remarkable jazz legacy is premiering at the Freep Film Festival.

We're gonna talk with one of the film's producers.

Plus a new exhibition here at the Detroit Institute of Arts pays tribute to African American filmmakers and actors from the early days of cinema.

Don't go anywhere.

"American Black Journal" starts now.

- [Narrator] From Delta faucets to Behr paint, Masco Corporation is proud to deliver products that enhance the way consumers all over the world, experience and enjoy their living spaces.

Masco: Serving Michigan communities since 1929.

Support also provided by the Cynthia & Edsel Ford Fund for Journalism at Detroit Public TV.

- [Narrator] The DTE Foundation proudly supports 50 years of "American Black Journal" in covering African American history, culture, and politics.

The DTE Foundation and "American Black Journal" partners in presenting African American perspectives about our communities and in our world.

- [Narrator] Also brought to you by Nissan Foundation, and viewers like you.

Thank you.

(upbeat music) - Welcome to "American Black Journal".

I'm your host, Stephen Henderson.

We're at the Detroit Film Theatre here inside of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

This is where the 11th annual Freep Film Festival is gonna kick off on April 10th.

The festival is produced by the Detroit Free Press and more than 20 feature-length documentaries and dozens of short films will have screenings over the course of five days at various locations in the city and suburbs.

One of the documentaries making its world premiere is "The Best of the Best: Jazz from Detroit".

It tells the story of Detroit's innovative and influential jazz musicians.

Here's a clip from the film, followed by my conversation with the documentary's co-producer and writer, Mark Stryker.

- It's about the meaning of music and jazz and the power of music and jazz, because a lot of times our formal education in school, we're focused mostly on notes, but we never really examined, like, the emotional aspects of music, the social aspects of music.

One, two.

(gentle instrumental music) Let's do it.

(gentle instrumental music) In Detroit, you are instilled with this idea that that is a part of your mission to mentor other folks from the time you first play, start playing.

It is like the "each one, teach one" philosophy is instilled in you by the time you're 15 years old.

How I choose folks to be mentored is sometimes I see the potential that this person can be a leader.

So I wanna mentor folks that are gonna mentor folks.

- Mark, welcome to "American Black Journal".

- Thanks.

It's great pleasure to be here.

- Yeah, it's really great to have you here.

You have been working on this material now, I think, for five or six, maybe almost 10 years.

Is that right?

- Well, you know, the book "Jazz from Detroit" came out in 2019.

I was 56 years old when the book came out, and I, like, people would ask, "How long did it take you to write the book?"

And I'd like to say, "Well, 56 years."

- Yeah, that's right.

All 56.

- But you know, once the book was out there, you know, a year later, right before the world shutdown in March of 2020, I went to Urbana, Illinois to give a couple of talks about my book, and I went to school at the University of Illinois.

So there were a lot of old friends there.

I was at dinner one night with some of them and one of them said, you know, "Have you ever thought about making a documentary out of your book?"

And I said, "No, but that's a really great idea."

And she said, "Well, look, I have these friends.

They're in New York.

They're filmmakers, and that's what they do."

And so she connected us and Daniel Loewenthal, Roberta Friedman, they are New York-based filmmakers, and they have deep experience in the documentary world and in the commercial world.

Dan is the director and the editor of the film.

And he's edited 20, 35, 40 Hollywood features.

And he's directed, the last film that he and Roberta did together, it's called the "Power To Heal: Medicare And The Civil Rights Revolution" that ran all over the country on PBS.

And Roberta is a producer and a filmmaker.

And she worked on "Star Wars", the original "Star Wars".

So, you know, deep experience.

They love Detroit.

They both love jazz.

And we started talking, and four years later, here we are.

- Here we are.

Right.

- Yeah.

- Yeah, so, I mean, the book, of course, focuses on the special role I think that Detroit plays the history of jazz.

Talk about how that gets enhanced through a documentary rather than a book.

- Well, it's actually been amazing to watch the sort of transformation of some of this material into a new form and to learn, because I don't know anything about, didn't know anything about filmmaking.

Now I do.

Seeing how that material can transform and really deepen and become a much richer experience in many ways for an audience.

So for instance, in the book, it's organized by these biographical chapters that highlight the contributions of these defining jazz musicians from Detroit.

And, you know, you can't tell everybody's story in a documentary film.

And so what has happened in the film is that Detroit itself has become a much richer and deeper character.

And we have embedded the history of jazz from Detroit and the stories of these great musicians within the rise and fall, and hopefully rise again, of Detroit's economic, social, cultural trajectory as an industrial power and the trials and triumphs of the African American community in Detroit.

So that material, which exists in some fashion in my book, kind of throughout, is really foregrounded in the documentary film.

And so we do tell the story of many important Detroit jazz musicians.

We follow them from Detroit to New York, and we see them influencing the rest of the world, can't tell the history of jazz without also telling the history of jazz from Detroit.

That's a big part of the film.

But also the story of Detroit and the conditions here that created this explosion of jazz in the middle of the 20th century and then sustained it all for the last 50, 60 years.

We keep producing great jazz musicians here, punching way above our weight class.

And so what I like to say, and I think what the film does very well is it shows you that what happened in Detroit was not an accident.

It was the result of particular social conditions, a particular community, and a variety of things and particular people and all of that sort of comes together.

- Yeah.

In some ways it's not terribly surprising because, I mean, this is a community that in terms of creation and creative energy, we have it in lots of different places, right.

I mean, so why not jazz is almost the right question.

- Yes.

And the answer to the question of when you go deeper and you say, "Well, why Detroit?"

You know, that's a story that starts with the Great Migration.

It brings, you know, hundreds of thousands of African Americans to the north to Detroit in the first half of the 20th century.

And it's the story of, you know, jazz is an expression of African American culture, right.

It's a music of improvisation, of adapting one's life to ever-shifting conditions, that is the African American experience.

And you see that play out, I think in our film, you know, the Great Migration brings all of these folks to the north, they're attracted by the auto industry, which is offering some of the best wages in the country for African Americans.

It builds a Black working in middle class.

In Detroit, that economic vitality creates the neighborhood of Paradise Valley, which is the economic and business center of Black Detroit in the middle of the 20th century.

All those clubs, hotels, bars, opportunities for musicians, and lay on top of that things like the Detroit public schools.

Some of the best music programs in the country, particularly at places like Cass Tech.

Cass was integrated.

So Black kids got the same opportunities there.

It's no surprise that Donald Byrd and Paul Chambers and Ron Carter, and many, many others, all came out of Cass Tech in the 1950s.

And much later, Geri Allen comes out of Cass Tech.

So you lay all that together and then you lay on top of that mentorship, which is a huge theme in our film.

And in the 1950s, Barry Harris, a great pianist, is the sort of professor of bebop, and he's training everybody that comes outta here.

And he sort of builds the DNA of mentorship into Detroit jazz.

That baton gets picked up generations later by Marcus Belgrave, a trumpet player.

And today that baton is being carried by the bassist, Rodney Whitaker, sort of the mentor in chief.

We followed those three stories through the film.

So all of these overlapping, interconnected conditions are very powerful set of conditions that don't exist in other places.

So you go, why Detroit?

Well, that's why.

- That's why, yeah.

And you can feel it still.

I mean, I went to see Herbie Hancock recently who was playing with Terence Blanchard.

And the atmosphere in the theater was even Herbie acknowledged like he was coming home.

It was as if he was a Detroiter.

And he kept referencing that the whole time.

And I kept thinking, you know, you wouldn't necessarily see that every place else, or not in the same way.

- No, you would not.

I mean, listening to Detroit is very powerful in an audience like that, because jazz is still a social music in Detroit.

And it's still a vital part of African American culture in Detroit.

And we still have a large African American population that comes out and hears the music.

And when you're playing for an audience in Detroit, you know, you're playing with people that went to high school with Geri Allen or Bob Hurst.

Or, you know, their parents went to school with Milt Jackson's family, or Tommy Flanagan's family, or they heard those guys coming up in Detroit.

So it's special.

The Detroit audience, you know, in the film, a couple of people say this, Dan says it that, you know, Detroit audiences, you can't Detroit audiences, right?

'Cause we know, we've been there.

We've seen it.

We've heard it.

So people know when they come to Detroit, they really gotta bring it.

And you can feel that.

Terrence, I should say too, Terence Blanchard is in the film.

He's one of three sort of big name jazz musicians from outside of Detroit that act as sort of commentators.

Pat Metheny is in the film.

Terrance Blanchard is in the film.

Christian McBride is in the film, all sort of paying homage to these great Detroiters that have come from here and influenced the course of jazz history.

- Yeah.

Yeah.

So the film is done and gonna premiere at the film festival.

Is there more for this material in your future?

You've got a book and a movie.

- A book and a movie.

You know, it's clear to me that the cultural soul of Detroit and the cultural soul in particularly of Black Detroit has become a life's work for me.

I mean, I grew up as a jazz musician.

I grew up idolizing Detroiters like Hank, Thad, and Elvin Jones and Joe Henderson, the saxophone player, and Paul Chambers.

These were all my heroes growing up.

Charles McPherson, who's great in the film.

And I've lived with their legacy for a long time.

And I'm hoping that, I don't know what's next in terms of this material for me, but I can't imagine leaving it behind for too long before returning to it in some way.

It's a rich legacy to mine.

- Yeah.

Yeah.

Alright, well congratulations on the film.

We will see at April 13th at the DFT.

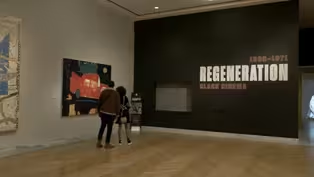

An exhibit, honoring the legacy of African American filmmakers and actors from the early years of cinema through the Civil Rights Movement is on display here at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

It's called "Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971".

The name is inspired by the 1923 independent movie "Regeneration", which featured an all-Black cast.

The exhibition traces the often untold story of African American representation in cinema history.

And it brings to light lost or forgotten films, filmmakers and performers.

I sat down with DIA curator and head of the Center for African American Art, Valerie Mercer, to find out more about this landmark exhibition.

Valerie, welcome to "American Black Journal".

- Thank you.

- Yeah.

It's great to have you back.

- I'm delighted.

- Yeah.

It's been a long time.

Right?

- Right.

It has.

- So I love the idea of this exhibit.

I wanna start by having you talk about how you came up with the idea for this exhibit and why it's so important to tell this story.

- Well, it's a show that was originally organized by the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in LA.

It's a Smart Museum, but doesn't have a long history.

But we are probably the second venue, I think, they opened the show, but I think it's such a great idea.

I've never seen an exhibition on film history.

But I love film, always have, it makes me happy.

Even when they're sad stories, I guess 'cause I'm a curator, you know, I just love visual stimulation.

But when it's a good story too, it makes me very happy.

So I'm so glad that we took the show.

And you know, it's so rich in history.

It covers 1898 to 1971.

And I'm sure a lot of people don't realize that there were Black filmmakers back in that time.

You know, up to, of course, the history really today, you know, it goes beyond '71.

But this is a really good coverage of the growth, the start, the development of that.

And now there's more Black filmmakers, which is wonderful.

- So, the time period where the exhibitions starts, of course, is really different from where it ends up.

Let's talk about that kind of early period, which I think is less familiar to people.

- I'm sure it is.

- Than the more recent period.

What was Black film making like at the turn of the last century?

- Sure.

Well, you'll even see in the exhibition there are race films and some of those, while there are Black actors in it, and actually even Black actors with black makeup on, because that was somewhat, almost like, as odd as it sounds, kind of became a standard.

Because of white performers always use- - The minstrel.

- Yeah.

But this is a Max Factor, Black makeup.

But that sort of came out of vaudeville, you know, number of the early performers because some of them were in the "Ziegfeld Follies".

And then from there some of them became, you know, interested in acting in films.

So like Bert Williams, some of the really famous vaudeville stars.

And there's a wonderful film, a piece of, sort of a segment, I think, of a film, or maybe it's a whole thing of, at the beginning of the show called, I think it's "Stolen Kisses."

And it's a gorgeous Black couple.

They actually are vaudeville performers, but it's like, it's, you know, so wonderful, intimate clip of this young couple kind of flirting with each other and then they kiss, you know.

And I remember I was telling Elliott, I remember being really young and the first time I ever saw a Black couple kissed on a big screen.

I remember actually sinking down in my seat and feeling uncomfortable.

But then very quickly I thought to myself, "Now why am I feeling uncomfortable?"

And I thought, "Oh, 'cause I've never seen Black people kiss on a big screen."

- On the screen.

- Yeah.

I've seen white couples.

And then I thought, I've only seen my mom and dad kiss.

But then I kind of thought to myself, yeah, I just gotta get used to this.

So then I sat up and over the years I became used to it.

But I remember it was lovely, you know, it was, I think it was like Sidney Poitier and Abbey Lincoln, "For Love of Ivy."

But I loved it, you know.

- Yeah.

- But we all have those first experiences, especially certain generations, you know, because, I mean, I remember the time when you saw, you know, an African American in a film, you told everybody.

'Cause it was so rare.

- 'Cause it was so unusual.

- Yeah, or if you saw them on TV, everybody in the family came to look at that person.

But, yeah, some of the early clips are really, really wonderful.

Because, you know, you see some of these famous performers and learn about them.

There's also, of course, you know, we have I think a poster showing "The Birth of a Nation" because that was such a highly publicized film.

And in a way, too, that was probably the first blockbuster in American film.

And Elliott always says, so many directors always in a sense trying to live that down.

You know what I mean?

Trying to surpass it 'cause it was so popular, you know.

But of course it was, you know, white supremacist on steroids, sort of, you know, when you see the film.

I think it's an important film.

I mean, I've actually seen it about three or four times.

First time I saw it, I was really kind of, like, nervous and uncomfortable, but then I thought, you know, just gotta get used to it 'cause it's important to know.

And I think in that way it's really important 'cause it had tremendous impact on American culture.

- Yeah, talk about why it's important to have this exhibition here in Detroit and here at the DIA.

- Yeah.

Where else would you have it?

This is the place, because we have such a wonderful history of showing film.

I think the theater now is about, we're about 50 years old and Elliott, of course, is still going strong and so are other people who work with him.

But, you know, I always tease him and say, I think most of the people who come to your programs or belong to their sort of auxiliary, I said, I bet they don't even look at a program.

They just trust you, and they just show up.

- They just show up.

- 'Cause they know you're gonna show them something good.

I mean, I was so happy when I discovered it.

'Cause I think when I was hired, I don't recall anybody mentioning it to me, but maybe after about a month I discovered it on my own.

And I said to Elliott, "You know, I was feeling homesick for New York, but once I discovered your theater and saw the programming, I thought, 'Wow, this is just like being in New York.'"

And he said to me, "That's the sweetest thing you could have told me."

But I mean, it's so top-notch.

You know, 'cause it's film's from all over the world.

So this is the place to have this exhibition.

I'm so glad we took it.

- And in Detroit, I think, the story that the exhibition tells has special resonance.

- Oh, yeah.

Well, there are some people connected in a sense with the project who come from New York.

One of the curators, Rhea Combs, you know, grew up here.

She was here, I think, opening night.

Just said some wonderful things.

She was almost getting choked up about her memories.

But, you know, there's certain actors in the, you know, some of the famous actors were actually born and raised here.

Then I guess went off to, you know, scenes Hollywood.

- Sure, yeah.

- But we have young filmmakers here too.

You know, we do.

I know not a lot of them, but a few of them have reached out to me and especially around the time of the opening of this.

And some them were here.

And said wonderful things about this show.

They were really happy about it.

- Yeah, and of course it dovetails with the other work you do here at the museum.

- Oh, oh, absolutely.

That's one.

- It's terribly important.

And I feel like has changed a lot over the years, right.

- Yeah, yeah.

Yeah.

I mean, it really supports my work as a curator of African American visual arts.

I usually, mostly, of course, work with paintings and sculpture and drawings and all that.

But telling that history, which I felt was so important, 'cause we don't get that in school.

I never got that.

What I learned, I really learned from my mom, you know, about the history 'cause she did know it.

But a lot of things I did not know.

But I learned it from her and then from friends over the years and just reading, you know?

And becoming more and more curious.

But, you know, that's why going into the exhibition makes me feel, you know, really happy.

'Cause, you know, there's some painful aspects of history, but a lot of it that I think does bring joy to most of us, to, you know, to see all these wonderful creative individuals, and learn about them.

I mean, some of the directors, you know, like Oscar Micheaux going practically door to door, he was so, in a sense, dedicated, but early on wasn't like he had a lot of people working for him, but he learned how to make films on his own.

And he did it kind of step by step, and then, yeah, wrote novels, turned them into movies.

But with the novels too, he go to door to door, he's selling them and did the same thing with the film.

But, you know, these are wonderful inspirations I think for younger generation filmmakers.

- Yeah, yeah.

Yeah.

Alright, well, it's always great to see you.

- And same here.

- Yeah, congratulations on the exhibition.

- Yeah, and I'm still listening to you on the radio.

- Oh, well, I appreciate that too.

- Okay.

- Thanks for being here.

- And thank you so much.

- Yeah.

And you can see the "Regeneration" exhibit through June 23rd here at the DIA.

That's gonna do it for us this week.

You can find out more about our guests at americanblackjournal.org and you can connect with us anytime on social media.

Take care.

And we'll see you next time.

- [Narrator] From Delta faucets to Behr paint, Masco Corporation is proud to deliver products that enhance the way consumers all over the world experience and enjoy their living spaces.

Masco: Serving Michigan communities since 1929.

Support also provided by the Cynthia & Edsel Ford Fund for Journalism at Detroit Public TV.

- [Narrator] The DTE Foundation proudly supports 50 years of "American Black Journal" in covering African American history, culture, and politics.

The DTE Foundation and "American Black Journal" partners in presenting African American perspectives about our communities and in our world.

- [Narrator] Also brought to you by Nissan Foundation, and viewers like you.

Thank you.

(gentle music)

Detroit Institute of Arts’ ‘Regeneration’ spotlights filmmakers, actors from early Black cinema

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S52 Ep15 | 11m 37s | “Regeneration” exhibit spotlights trailblazing filmmakers, actors from early Black cinema. (11m 37s)

‘The Best of the Best: Jazz from Detroit’ documentary

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S52 Ep15 | 12m 25s | A documentary telling Detroit’s jazz legacy premieres at the 2024 Freep Film Festival. (12m 25s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

American Black Journal is a local public television program presented by Detroit PBS