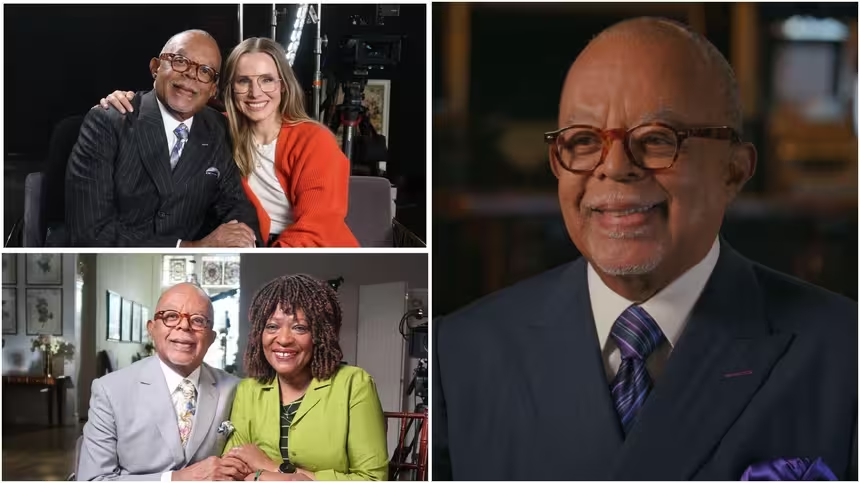

Finding Your Roots

No Laughing Matter

Season 5 Episode 7 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Dr. Gates reveals the histories of comedians Seth Meyers, Tig Notaro and Sarah Silverman.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. shows comedians Seth Meyers, Tig Notaro and Sarah Silverman that their family trees are filled with people whose struggles laid the groundwork for their success. Gates also reveals to each one news of an unexpected DNA cousin.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

No Laughing Matter

Season 5 Episode 7 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. shows comedians Seth Meyers, Tig Notaro and Sarah Silverman that their family trees are filled with people whose struggles laid the groundwork for their success. Gates also reveals to each one news of an unexpected DNA cousin.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGates: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr., welcome to "Finding Your Roots".

In this episode, we'll meet Sarah Silverman, Seth Meyers and Tig Notaro.

Three comedians whose first and favorite audiences were their families.

Silverman: As a three-year-old, I would swear, and all the adults laughed and laughed, and I was like it just felt like glee!

Notaro: My mother thought I was successful when I was calling her saying I had just done a set at this gross bar in front of two people, and she'd be like, "Yeah, are you having fun?"

Meyers: My mom has been the laugh track of my life.

She once came to an "SNL" where I told a joke in weekend update that bombed with 200 people, and I heard her laugh.

Gates: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists stitched together the past from the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts used the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

This is the book of life for Seth Meyers.

And we've compiled it all into a book of life, a record of all of our discoveries.

Silverman: Oh my God, how is there a photograph of this?

Meyers: I did not know this.

That's fantastic.

Gates: It's fascinating to me that no one in your family ever mentioned this story.

Notaro: Yeah.

Gates: That's a big deal.

Notaro: That's a huge deal.

Gates: Seth, Sarah and Tig have won fame by drawing on their families both for material and for inspiration.

But now the size of their families is going to grow, exponentially!

In this episode, they'll meet ancestors whose names they've never heard before, revealing roots that stretch back centuries, hearing stories they couldn't have imagined.

(Theme music plays) ♪♪ ♪♪ Meyers: Do those last three?

Gates: Seth Meyers has a boyish charm but he's a comedy veteran.

A beloved mainstay of late-night television for almost two decades.

From his early days on "Saturday Night Live", to his current gig as the host of his own show.

Seth has earned praise for his quick wit, and sharp intelligence.

Meyers: This week Apple released a thing that does stuff that its other stuff already does.

Trump ends every tweet like he's jumping out from behind a door to scare you.

Congress, get ready to do your job.

DACA.

Gates: In a constantly changing world, Seth somehow is able to bring out the humor in almost everything.

Meyers: Mr.

President, look at your hair!

If your hair gets any whiter the Tea Party is going to endorse it!

Gates: It's an exceptional talent.

And it didn't surprise me to learn that Seth's been honing it his entire life.

Meyers: Comedy was the currency in our family, my brother and I would watch "Saturday Night Live" when it aired, and then we would tape it and show our favorite parts to our parents when they woke up Sunday morning.

We were always sort of enjoying it together, and if not, we were trading the things we loved, Gates: When did you realize you were funny?

Meyers: The first time I made my dad laugh.

My dad's very funny, and he's also a very tough audience.

So, it was probably around eight, nine years old that I thought I might have a sense of humor worth bringing out to the world.

Gates: Seth told me that as he grew up, his sense of humor evolved in dialogue with his father.

The two of them listened to comedy albums together, and many of Seth's earliest jokes poked fun at the foibles of his family.

But making his father laugh was one thing.

Getting the world to do it was quite another.

Seth spent years on the improv comedy circuit, honing his craft trying to break through.

But his success, when it came, was almost completely accidental.

Meyers: We were doing our show at the Chicago Improv Festival.

Randomly, this woman, Ayala Cohen, who worked in the talent department of "Saturday Night Live," was visiting family in Chicago.

She thought, "Oh, I'll just roll over and see a little comedy tonight," and uh... Gates: And you didn't know she was there?

Meyers: Didn't know I was there.

She called after, I thought it was a joke, because again, you're doing a show in a little theater in Chicago.

You never think a talent scout from "Saturday Night Live" is gonna be there, seems like something from a 1940s musical, you know, that, yeah, I didn't think it actually happened that way, that somebody calls and goes, "I saw you and you look like a million bucks."

Gates: That phone call transformed Seth's life, much as if he really was a character in a Broadway musical.

Leading to a cast spot on "Saturday Night Live", which launched his entire career.

Meyers: I'm Seth Meyers and here are tonight's top stories.

Gates: Looking back, he still can't believe it happened.

And he still treasures his memory of the call he made to his father to share the news.

Meyers: I told my mom first, and uh, I told her not to tell him.

And he, I remember telling him, he was so impressed that she had kept the secret.

And to this day, I think, you know, he was blown away that I got on the show, but the fact that for two hours, she knew this news and managed to keep it from him really, really blew his mind.

Gates: So, are you still trying to please your father when you do a routine?

Meyers: Yeah, I am.

I would, yeah.

Yeah.

It means, it is the piece of feedback that is most important to me.

Gates: My next guest is comedic superstar Sarah Silverman.

Sarah's been in more films and television shows than I can name, and she's one of the funniest stand-up acts that you'll ever see.

Silverman: I'm great with kids.

Like toddler age, like two-year-olds.

If their parents like introduce me I like to go 'I'm your new mommy.'

Gates: Like Seth Meyers, Sarah told me that her sense of humor was forged in her childhood home.

But she grew up in a very different kind of home.

Her parents divorced when Sarah was seven, after a marriage so contentious that its end brought a sad kind of relief.

Silverman: I remember when they sat us down and told us, I was thrilled.

My other sisters were crying, they were upset.

I, I was thrilled, and I remember them saying, "Oh, she doesn't understand," and I remember thinking, "What's not to understand?

They're not gonna, are you gonna be fighting anymore, are you, wake me up at night screaming?

No?

Great."

Gates: It's easy to see how the turbulence of Sarah's childhood has informed her comedy.

Less obvious, but just as significant, is the town in which she was raised: Bedford, New Hampshire.

Where Sarah was one of the few Jewish kids in her school, a fact that shaped her ironic voice almost as strongly as her parents' troubled marriage.

Silverman: It, it's funny, because my feeling Jewish always came from being, um, the only Jew.

So it's like, we were, we had no religion but because I had this kind of intuition when I would go to my friends' houses to make sure their parents knew I was not scary, and you know.

Gates: But Sarah, where did that come from?

I think a Black person in a white community would've had the same impulse.

Silverman: Yeah.

Well, like, like all of us, and especially comedians, but also all humans, we figure out how to survive our childhood, you know?

And with comedians, we, we become funny as a survival skill.

You know, the fat kid who makes fat jokes before anyone else, you know?

Gates: Right.

Silverman: I was the hairy little Jewish monkey in a sea of blond, um, kids, and uh, you learned to ingratiate yourself, to, to, you know, be non-threatening, to be funny, you know?

Gates: Sarah's survival skills have served her well.

She's been working in comedy since she was a teenager.

But her career didn't follow a straight path to stardom.

In 1993, when she was just 22, she was hired by "Saturday Night Live", but she only lasted a season.

Silverman: This is ridiculous.

Screw this!

Gates: That setback would have derailed many, but Sarah, hardened by experience was able to transcend it.

Silverman: Looking back, I don't take it personally.

They probably did the right thing.

Lorne has a pretty good eye.

Gates: But what kept you going?

I mean, was it traumatic to be let go?

Silverman: Yeah, I remember my agent and my manager who suddenly scooped me up when I got "Saturday Night Live" was suddenly not as interested in me, and I went back to stand-up, and you know, just doing that full-time.

And I never really think about the future.

I still don't, probably to my detriment.

But I just kind of immersed myself in stand-up, 'cause that's just all I ever wanna do.

Gates: My third guest is Tig Notaro, an extraordinary comic.

Notaro: Clown horn.

Fa-fu.

Gates: Beloved for her deadpan delivery and low-key persona.

Notaro: If you don't like that then you just don't want joy in your heart.

Gates: A persona that, Tig says, emerged in her childhood, in direct response to her mother.

Notaro: Well, my mother was just really, really wild.

She was, I guess, a free spirit, an artist.

Um, she was, you know, the funniest person in the room.

And I think that's why I'm mellow, is because she was so loud and gregarious and wild and funny, and-and then, I think I, you know... Gates: Toned that down.

Notaro: Well, I just, yeah, I was watching my mother on her stage all through life, and um, and so, I think it kind of quieted me a little bit.

Gates: Tig's quiet style has proven to be remarkably popular.

And she's maintained it in the face of some daunting personal challenges.

In 2012, she contracted a dangerous bacterial infection, from which she barely survived, only to find herself diagnosed with cancer.

At that point, not everyone would've continued to find life so funny.

Tig simply changed her act.

Notaro: Before I had a double mastectomy I was already pretty flat-chested and I made so many jokes over the years about how small my chest was that I started to think that maybe my boobs overheard me and were just like, "You know what?

We're sick of this.

Let's kill her."

I wanted to perform, I wanted to get onstage, and I wanted to see if I could make light of what I was going through, and I didn't know that I'd be able to do it.

Um, I thought that there was a pretty good chance that I would share what was going on, and the audience would be mortified.

Gates: Mmm-hmm, freaked out.

Notaro: Yeah, and then I'd walk off in silence, and be like, "Why did I do that?"

And then I'd go die of cancer, you know, and that was my last performance.

Gates: Fortunately, Tig's gamble paid off, propelling her career to even greater heights, including an award-winning Amazon series based on her recovery from cancer.

Looking back, I'm amazed at what she's overcome.

But, in keeping with her character, Tig takes it all in stride.

Do you ever think about giving up?

Notaro: No.

No.

No.

I used to cycle, I used to do long-distance cycling, and my favorite part of cycling was uphill, and sometimes as long as eight miles uphill... Gates: Jesus.

Notaro: Just slowly, that was my favorite kind of cycling, was just barely moving, and I would pass other cyclists that would get off in the middle of the hill and rest, or walk, and I'd be like, "Nnn-nnn", 'cause to me, that's harder.

Gates: Yeah.

Notaro: To get back on the bike... Gates: Oh my God.

Notaro: Or to walk the bike... Gates: Yeah.

Notaro: Is so much harder than to stay on and finish, and to me, it's very much who I am, I think.

Gates: Yeah, it's a metaphor for who you are.

And how you coped.

Notaro: Mmm-hmm.

Gates: Tig, Sarah, and Seth share an abiding conviction: All three believe that they were shaped to an uncommon degree by their parents.

Now it was time to look at their roots, to try to uncover ancestors who may have influenced them as well, even if their stories weren't passed down.

I started with Seth.

Unlike my other guests, he'd actually done his family tree before, back in the seventh grade.

The results, however, weren't exactly accurate.

Meyers: This was a story that I had forgotten, but my dad told at my wedding, which is I made it all up.

I was supposed to do research and ask my parents where my family, my ancestors were from, and I just made it up, and uh, got an a, and then my dad read it, and was very taken aback by the fact that I had fabricated my entire history.

Gates: Did, did you, did you ever confess to the teacher?

Meyers: No, I don't think we ever did.

My dad, uh, I think my dad understood that I was, probably my future was going to be more in creative writing than history, and so, he appreciated that I followed the path of least resistance.

Gates: We set out to do the research that Seth had so cleverly avoided, and we soon found ourselves in a small town in Lithuania, called Kalvarija.

Records place Seth's father's family here as early as the 1860s.

When it was still part of the Russian empire.

Seth had never heard of the town, or of the surname that his ancestors used when they lived here.

Meyers: "Mejer Trakianski, blacksmith."

Gates: Guess who that is?

Meyers: Wow.

Trakianski is the last name?

Gates: You have just met your great-great-grandfather, and you have just retrieved your original family name.

Meyers: Wow.

"Late Night with Seth Trakianski."

Gates: Yeah.

I can see it now.

Meyers: Yeah.

Amazing.

Gates: How does it feel to learn that?

Meyers: It's funny to think of how, I don't know, how much weight names have on people's outcomes, um, 'cause that, that's a, that's a lot of a name there.

Gates: We wanted to figure out how the Trakianskis would become the Meyers.

The decision was likely made by Seth's great-grandfather, who took the name "Morris Meyers" after immigrating to America.

We aren't sure why Morris changed his name.

He may have been trying to assimilate.

He was certainly a very resourceful man.

Records show that he came to Pittsburgh around 1870, and started out at the very bottom, as a peddler.

Meyers: "He came to this city, where in common with other pioneers, he sold tin in the country districts, often carrying great loads of pots, pans and other utensils.

The first $4 he earned he sent back to his mother."

Gates: Can you imagine making a living carrying pots and pans in the countryside around Pittsburgh?

Meyers: I mean, no.

I certainly don't hear it and think, "I missed my calling."

Gates: When Morris arrived in Pittsburgh, there were only about 1,000 Jewish people in the city.

It was a tight-knit community, and Morris had relatives within it who seemed to have helped him get on his feet.

By 1880, Morris was married to a woman named Rosa Cohen, who was likely one of these relatives.

And Seth, I have to tell you that we learned something about this marriage.

According to multiple family members, Rosa and Morris were first cousins.

Meyers: Oh, wow.

Gates: You didn't know anything about this?

Meyers: No.

Gates: So, you know what, if they were first cousins, that makes you your own fourth cousin.

Meyers: Oh.

Well, look at that.

Fun to find out.

Gates: Have you ever seen those pictures?

Meyers: I have never seen these pictures.

Gates: Those are your great-grandparents.

Meyers: Alright.

Gates: Any family resemblances there?

Meyers: I mean, I guess I see a little bit in, uh, a little bit of my face, my brother's face, my dad's face in Morris here.

Gates: Mmm-hmm.

Meyers: Not a lot of Rosa.

Gates: What's it like to see those for the first time?

Meyers: It's really strange to just think about how nothing they were worried about are the things that I'm probably worried about.

And Rosa, let's be honest, looks like a lady who had some worries.

Based on her photo.

She doesn't look, she doesn't look free and easy.

Gates: No.

I wanted to give Seth a sense of what lay behind his great-grandparents' worried faces, but records were scarce.

We believe that Morris came to America when he was only about 15 years old... arriving at what was known as the Castle Garden Immigration Center, a precursor to Ellis Island, situated near what is now Manhattan's Battery Park.

From there, Morris traveled to Pittsburgh, a distance of over 300 miles!

Think about this, he's 15, he'd have to find food, lodging, and train tickets, and according to your family, he spoke zero English.

Meyers: I can't even... Gates: It's mind-boggling.

Meyers: And it's not, I mean, it would be hard enough to get to the Bronx from Manhattan.

Gates: Yeah, true.

Meyers: But Pittsburgh.

Gates: Yeah, with no money.

What's it like to look at that, and to think of him at the age of 15?

Meyers: Well, you know, one thing is to think of how close I live now to Battery Park.

I don't ever think about that, how close I am to the gateway to where this all started.

And yeah, you know, when I think about the things in my life that I would frame as difficult, none of them are even close to any sort of level of difficulty that someone like Morris went through.

Gates: Yeah, talk about being forced to grow up overnight.

Meyers: Yeah.

It is amazing.

Gates: Morris did more than grow up fast, he thrived.

He launched a dry goods business and eventually bought a home in a desirable Pittsburgh neighborhood, a home where Seth's relatives still live today.

Meyers: It's still owned by family?

Gates: Yeah.

Meyers: That's fantastic.

In a nice neighborhood, too.

Gates: Do you think that Morris' resourcefulness is something that's been passed down in your family?

Meyers: I think that his resourcefulness was born of necessity and even if he loved improv comedy, it doesn't seem like he was in a place where he could of taken that chance.

Gates: He could've been pretty funny on the, with his horse, but then, cart.

Meyers: I think, you know, I think if you're a peddler, if you got a joke or two, that probably helps make a sale, uh, so we don't know, so I guess that's what I'm really taken with is you know, you realize, you know he didn't have the chance to choose what his passion was, you know, he had to find something that worked and uh, the fact that he did it in a way that, you know, bought a house that's still in the family is, is uh, quite a legacy.

Gates: Like Seth, Sarah Silverman has roots that stretch back to Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.

But as we began to excavate those roots, we immediately encountered a character who was far less benign than Morris Meyers.

Sarah's maternal grandmother was a woman named Goldie Trapsky.

According to the family, Goldie was an abusive mother, harboring many demons.

Sarah knew her growing up, and even as a child, she was aware that Goldie had some very serious issues.

Silverman: She was kind of a monster.

I mean, I should have compassion for her, she was crazy.

She was very smart.

She, but she, I think she lied.

I wasn't sure what to believe, the things she would say.

I remember going to the market with her when I was visiting her, and she was telling someone, "She's playing Annie in Boston."

And I said, "No, no, not in Boston.

It's just in Concord," and then we got in the car and she's like, "Why did you tell them that?

Why can't they just think it was in Boston?"

Gates: She did?

Silverman: Yeah, and I'm like, "Why can't it be enough that it's in Concord?"

Gates: Sarah believes that Goldie was afflicted by an ingrained sense of shame.

Untangling her story offered us a chance to understand how and why that happened.

We started with the 1930 census for Hartford, Connecticut, where we found Goldie as a young woman, living with her parents, Samuel and Ida Trapsky.

Silverman: "Samuel Trapsky, 39.

Occupation: Auctioneer in a jewelry store.

Ida Trapsky, wife, 37.

Goldie, daughter, 18."

Gates: Have you ever heard of them?

Silverman: No.

Gates: Well, you just met your great-grandparents.

Silverman: Sam and Ida.

Gates: Sam and Ida.

Now, as you can see, Samuel, Ida, and Goldie were all born in Russia.

Silverman: Oh, and their language is Yiddish.

Gates: Did you ever hear Goldie speak Yiddish?

Silverman: No, no.

She talked, like, very, um, you know, I think she was putting on, like everything, every other part of her, like, building on the truth, like the truth couldn't be okay.

Gates: As we dug more deeply, it became clear that Goldie's troubles were bound up in her experience as an immigrant and that that experience had been profoundly disruptive.

In the 1920 census, we found Goldie's father Samuel in Connecticut, living on his own.

Silverman: "Samuel Trapsky, boarder, 28 years old.

Married."

Gates: Your great-grandfather was one of two boarders, living in the home of an Italian widow and her six children.

Silverman: Really?

Gates: Yeah.

What's it like to see that?

Silverman: I, I'm trying to digest it.

I wish I could, like, talk to him or meet him or something... Gates: Now, remember, your grandmother Goldie was born in 1912, right?

So, when that census, remember, the census taken in 1920... Silverman: She was eight.

Gates: Goldie was about eight years old.

So, where's Goldie?

And where's Goldie's mother?

Silverman: It just says "married."

Gates: We discovered the answer to this question in Samuel's naturalization papers, which revealed that he had come to America alone, leaving his family behind in Russia waiting for him to secure a foothold before sending for them, an arrangement that, while common, must have been agonizing both for them and for him.

Records show that Goldie and her mother waited roughly seven years for Samuel to summon them, then they set off on the arduous journey to join him.

We found evidence of that journey in a ship's manifest from 1921.

Silverman: Oh my gosh.

Gates: That records the moment that Goldie and her mother arrived in the United States.

Silverman: Sailing from Liverpool.

Gates: Mmm-hmm.

Silverman: So, they had to get to England.

Gates: Right, from Russia.

Silverman: It's pretty wild.

Gates: Could you please turn the page?

Silverman: There she is.

Whoa, so, that's Ida.

Gates: That's Ida.

That's a photo of Ida and Goldie in 1921, likely from around the time that they emigrated.

Silverman: Crazy.

Gates: Isn't that amazing?

Look at their faces.

Silverman: She looks like my sister Susie.

Shaved head, weird necklace for a little girl.

Probably, like, a toy necklace.

It looks like a costume from, like, "Fiddler on the Roof."

Gates: It does... What do you think it was like for them, coming to a new country where they didn't speak the language, they didn't know the culture?

Silverman: I can't imagine the terror and the fear, the... I mean, as humans, we already, like, fear what we don't know, like, fear the unknown, and this is, like, real unknown.

Gates: Mmm-hmm.

Silverman: I wish I knew what Ida was like.

There's no sense, 'cause she just looks terrified here.

Gates: The Trapskys would ultimately flourish in America.

By 1940, Samuel owned a business, and he also owned a home.

But for Goldie, the damage had already been done.

Goldie rarely spoke about her childhood, and learning about it provided Sarah with a painful insight into her grandmother's character.

Silverman: I wonder about it.

I mean, it's something my therapist says, when you're in survival mode, you can't thrive, 'cause you're just surviving.

Gates: Mmm-hmm.

Silverman: And they were always surviving, you know?

Gates: Yeah.

Silverman: And even when they found success, they're still in survival mode.

You know?

Gates: Yeah.

Silverman: There's like an un-fillable hole.

Gates: Mmm-hmm.

That's a good way to put it.

Silverman: It's sad.

Gates: Much like Sarah, Tig Notaro grew up in a family shaped by a complicated individual: her maternal grandmother, Mathilde Fitzpatrick.

Mathilde's very name evokes a bygone era, and her personality seems to have been an extension of her name as she strove to retain her family's ties to the past.

Indeed, Tig believes that her mother's wild spirit was, in many ways, a response to Mathilde's reactionary spirit.

Notaro: My grandmother was a very uptight, conservative, person.

People have told me that she was fun at parties and all this stuff, but I know she was very much into things looking right, and appearing right, and I think my mother really rebelled against that.

And you know, even as a kid, my grandmother, she would be upset when I was wearing jeans or the fact that my mother bought me an electric guitar when I was little and my grandmother was like, oh, Susie, no that's my little girl and my mother was like oh, Mother relax, you know?

I think she didn't want us to, to be confined in the ways that she felt confined.

Gates: Mathilde's sense of propriety was well earned.

She descended from a very prominent family.

Her grandfather, John James Fitzpatrick, served as the mayor of New Orleans, and he was a larger-than-life figure.

His portrait even hangs in Tig's house.

But perhaps because he's so celebrated, Tig has never felt compelled to learn the details of John's life.

Notaro: I really feel like my family is so excited by the fact that he was the mayor of New Orleans, that nobody ever talked about anything else, you know?

Just like, "Yeah, no, Tig's..." Gates: Well, that's a big deal.

Notaro: It is a big deal.

Um, but I don't really know.

I, I'm sure there's been some things I've been told, but I really haven't followed it.

Gates: She may not have known it, but Tig was about to start following John's story in a big way.

When we sent our researchers to Louisiana, we found the future mayor of New Orleans in a very unexpected place.

Would you please read the transcribed lines?

Notaro: "Register of boys received into the asylum.

Name of the boy: John Fitzpatrick.

Age when received: Ten years."

Gates: That's your great-great-grandfather.

He's ten years old, living in an asylum.

Notaro: He was an orphan?

Gates: He was an orphan.

St.

Mary's was a home for orphans and destitute children.

Notaro: Wow.

Had no idea.

Gates: What's it like to see that, to learn that?

Notaro: I mean, I'm all of a sudden so genuinely curious about his life and what led him to that, and yeah.

Gates: John's path to Saint Mary's was painful to contemplate.

In 1851, John's father, James Fitzpatrick, died when John was just seven years old, leaving his mother Catherine alone to care for six children.

At the time, there was a limited system of public welfare, so single parents were often faced with an agonizing decision.

And Catherine placed at least three of her children in the orphanage.

I mean, can you imagine being in Catherine's position, being forced to do that?

Notaro: Nnn-nnn.

No.

I don't know how people, that's something I don't think I could get through.

Gates: Yeah.

Notaro: Deadly diseases, sure, but not abandoning a child.

Gates: Well, and let's think about it from John's point of view.

He loses his father suddenly, and then basically overnight, he's in an orphanage.

Notaro: Wow.

I'm truly stunned.

Gates: Happily, John would be reunited with his mother sometime around his twelfth birthday, and then began an incredible ascent.

He worked his way up in the carpentry trade, got involved in local politics, and against the odds, was elected the mayor of New Orleans in 1892.

Notaro: "The blue-shirted citizens bear John Fitzpatrick to the City Hall."

Gates: That's your great-great-grandfather John on the day, he became mayor of New Orleans.

Any idea what "blue-shirted citizens" are?

Notaro: Um, the, um, middle class, or...?

Gates: Blue-collar workers.

Notaro: Blue-collar workers.

Gates: John was known for his support of the working classes.

He never lost his, his roots, you know, his support for... Notaro: Yeah.

Gates: His class peers.

Notaro: That's nice.

Gates: Yeah.

Notaro: I love, um, loyalty.

Gates: I do too.

Was this ever discussed in your family?

Notaro: I mean, I truly, the only thing that I know about him is just this man in a picture.

It's like, "Hey, he's the, he's the mayor."

I really, I don't know any of this.

Yeah.

Gates: John Fitzpatrick's success extended well beyond politics.

He went on to become the president of a fruit company accruing wealth and helping to create the world into which Tig's mother was born.

The world she ultimately resisted, which would allow Tig to follow her own path.

Does knowing all of these new details begin to change the way you think of your mother?

You know, we're all repositories of all of these experiences, whether we know it or not.

Notaro: Yeah, definitely.

I mean, I think it just highlights how nice it is that she took different routes and turns in life, and, and made way for me to have the life that I have.

Yeah.

I just think, I love that all of this is here also for my kids.

Gates: Forever.

Notaro: Yeah.

Gates: None of this will ever be lost again.

Notaro: Yeah.

Gates: We'd already traced the roots of Sarah Silverman's maternal grandmother, Goldie, a woman who was, by Sarah's own description, monstrous.

Now we turned to someone who played a much happier role in Sarah's life.

Goldie's husband, Sarah's grandfather, Herman Halpin.

A successful businessman who provided for his family both financially, and emotionally.

Silverman: I loved him.

He was very funny, and oh, he would've loved the modern world, because we would be on the phone, and he'd say, "Oh, you look good.

I'm looking at you through Phone-O-Vision."

And he'd always pretend he could see me, and how I looked nice, you know, whatever, and he loved jokes, and whenever we'd pass the cemetery, he'd say, "Oh, people are dying to go there."

And he just loved jokes.

Gates: Sarah's affection for Herman was palpable, but when it came to his roots, she knew even less than she'd known about Goldie.

We began with his birth certificate, which immediately revealed a surprise.

Silverman: Hyman Cohen?

Is that my grandfather?

Gates: That's your grandfather's birth certificate.

Silverman: Hyman Cohen?

Herman Halpin is really Hyman Cohen?

Gates: He changed his name from Cohen to Halpin when he married your grandmother Goldie.

Silverman: Oh.

Wait.

She didn't want people to know they were Jewish?

Gates: We think that it was because she wanted them to have a more "American"-sounding name.

Silverman: American.

Yeah.

Gates: And they never said, "We changed our name."

That's amazing.

Silverman: I had no idea, Hyman Cohen.

I used to have a joke, I wanted to name my first kid Hyman after my great-great- grandmother's hymen.

That was my joke.

I forgot about that joke.

Gates: Now that we'd straightened out Herman's name, we began to explore his roots.

We learned that he'd been born in Seattle to two Jewish immigrants from Russia, Sarah's great-grandparents, Morris Cohen and Anna Berg.

And we found a portrait of the family that Sarah had never seen before.

Silverman: Whoa.

That's incredible.

Wait, is that my grandpa?

Gates: That's right.

That's Herman.

Silverman: Wow.

So that's Morris?

Gates: That's Morris, exactly, your great-grandfather.

Silverman: He looks like a tough guy.

Gates: Yeah.

Silverman: Look at that.

The Cohens of Seattle.

Gates: This photograph seems to show a family on the road to prosperity.

And Herman, did, in fact, flourish as a business man.

But his success likely came in spite of his childhood.

According to Sarah's relatives, Herman's father Morris presided over an unstable home.

He moved his family frequently, worked a variety of odd jobs, and could be a very difficult man.

Now Sarah, we heard that he had a gambling problem, that the pantry was often bare.

Silverman: Oh... Gates: And there were a lot of mouths in that photograph to feed, and that he mistreated his wife Anna and the children.

Silverman: I bet my grandfather took care of his sisters.

Gates: Think so?

That's the kind of personality he had?

Silverman: Yes, that's my guess.

He's had to persevere, to survive, and take care of his family.

You know, there's always that complexity of, like, looking up to your father even though he's a gambler, has a temper, you know?

Gates: Yeah.

Silverman: I just wish I could, like, jump into the picture and be like, "What's going on?"

Gates: We have no way of knowing if all of the family stories about Morris are true, but we uncovered evidence to support some of them.

Records revealed that the Cohens did, in fact, move frequently.

We found them in Gainesville, Florida, in Boston, Massachusetts, and even London, England among other places.

And we found something else as well, something that allowed us a glimpse into Sarah's deeper roots.

There's one more thing I want to show you.

Would you please turn the page?

Now, Sarah, this is your great-grandfather Morris's death record, from Providence, Rhode Island, 1954.

Silverman: Now he's in Rhode Island?

Gates: Yep.

He and Annie had settled there by 1930.

Would you please tell me the names of Morris's parents?

Silverman: "Hyman Shlamie Cohen.

Birthplace: Russia.

Mother: Mary Libby.

Birthplace: Russia."

Hyman Shlamie Cohen.

That is so Jewish.

Shlamie.

Gates: You just met your great-great-grandparents.

Have you ever heard of these people?

Silverman: No.

I don't know these people.

But I only exist because of them.

It's bananas.

Gates: We had already introduced Seth Meyers to his paternal ancestors who immigrated from Eastern Europe.

Now we had a very different kind of immigration story to share with him.

It began in England, where Seth's maternal great-grandfather, Frederick Whetham, was born in 1886.

Frederick came to the United States as a young man.

By 1916, he was married and the father of a child.

But World War I was raging in Europe.

America had not yet entered the fight, and England was in peril.

So Frederick made an astonishing decision.

He headed north, to join the Army of Canada, which was, at that time, still part of the British Empire.

Meyers: Wow.

Gates: Can you imagine leaving your wife and child behind to go fight in World War I?

Meyers: And, yeah.

Also to be willing to leave England, but obviously his heart stayed there.

Gates: Yeah.

Meyers: The fact that he wasn't willing to forget that part of himself.

Gates: Yeah.

Meyers: Yeah.

Gates: And to go fight, I mean, the risk, you know... Meyers: To go fight, via Canada.

Gates: Yeah.

Meyers: Yeah.

Gates: It's amazing.

Frederick's decision thrust him into some of the worst fighting of the war, in a small Belgian village known as Passchendaele.

Here, in the summer of 1917, the British and their allies launched an offensive, hoping to strike a decisive blow on the stalemated Western Front.

The attack began in late July and went nowhere.

By October 1917, this was the scene in Passchendaele.

The Allies had barely advanced and do you see what the soldiers are standing in in all these photos?

Meyers: Just mud.

Gates: The heaviest rains in 30 years had turned the grounds into a sea of mud-filled craters.

Meyers: Wow.

Gates: Can you imagine?

Meyers: No.

Gates: So, think about it.

The Brits, realized that they had to look for reinforcements.

Can you guess who they turned to?

Meyers: The Canadians.

Gates: Please turn the page.

This is from the New York Times, November 7, 1917.

Would you please read the highlighted passage?

Meyers: "Climax of struggle elates Canadians war correspondents' headquarters, November 6.

In a heroic attack by the Canadians this morning, they fought their way over ruined Passchendaele and into the ground beyond it.

If their gains are held, the seal is set upon the most terrific achievement attempted and carried through by British arms in this war."

Gates: Isn't that cool?

Meyers: That's fantastic.

Gates: Under continuous rain and shellfire, the 100,000 Canadian troops succeeded.

And your great-grandfather Frederick was there.

Isn't that amazing?

Meyers: That is amazing.

Gates: All told, over half a million men were killed, wounded, or otherwise lost at Passchendaele.

When the smoke cleared, Seth's great-grandfather was still alive, but he hadn't emerged unscathed.

Records reveal that he was struck by a high explosive shell, and permanently scarred.

Frederick was wounded on the final day of the battle.

Meyers: Ain't that somethin'.

Almost.

Gates: Yeah.

Meyers: Yeah.

But I guess it could've been worse.

Gates: What's it like to learn this?

Meyers: You just realize how many things have to go right for any of us to be here.

Gates: Oh, yeah, big-time.

Meyers: You know, the amount of people that just have to survive for me to be here, and for my kids to be here, and-and you just realize that, you know, 100 years ago in Belgium, the high-explosive shell missed by a foot.

Gates: Yeah.

Meyers: And uh... Gates: Erase.

Meyers: Everybody's gone.

Gates: No Seth.

Meyers: "Back to the Future"s out.

Gates: Gone... I want to show you something.

Would you please turn the page?

Meyers: Gosh, it's that feeling, maybe a little bit of my brother in there.

Gates: So, you see the resemblance between your brother, but not you?

Meyers: A little of me too, yeah.

Gates: Yeah, we think so.

Meyers: Yeah, man.

It's so funny, 'cause I always thought I looked like my dad's side.

Gates: Mmm-hmm.

Meyers: Yeah.

That's something else.

Gates: His British roots are your British roots too.

Meyers: Mmm-hmm.

Gates: Do you think of yourself as British?

Meyers: I really don't, but you know, I'm obviously aware I have roots.

We knew, uh, what part of the world they were from, but I didn't know much more than that.

Gates: Well, let's see how British you are.

Meyers: Alright.

Gates: As it turns out, Seth is extremely British.

We were able to trace his English ancestry all the way back to his eighth great-grandfather, a man named Andrew Whethem, who was born in the early 1600s.

Meyers: That's something else.

Gates: How does it feel to see your ancestors from more than 400 years ago, listed by name?

Meyers: And not just name, I mean, birth and death and... Wow.

This whole thing gives you just such an appreciation for people who in the present understand that the future will want to know about the past.

I feel like we live in a time where people are only focused on the present, and they're not thinking about what the future is gonna need.

And the fact that somebody, you know, with this incredibly basic technology, created a record that still lives is, uh, it's insane.

Gates: It's a miracle.

Meyers: It's a miracle.

It's really mind-blowing.

Yeah.

I mean, I'm just blown away.

Gates: Turning from Seth back to Tig Notaro, we had another soldier's story to tell.

But this one had a decidedly darker outcome.

It began in the records of the Confederate military, where we found Tig's third great-grandfather, a man named Aristide Renaud.

Aristide served in the 8th Louisiana Infantry during the Civil War, and succumbed to illness after it ended.

His demise is set down in a pension application filed by his widow.

Notaro: "Comrade Renaud joined the army in the autumn of 1862, leaving behind wife and three children without means of support but kind Providence.

Not long after his return home, Renaud's health failed him, having been attacked by 'galloping consumption' which caused his death."

Galloping consumption?

Gates: Yep.

Notaro: I'm surprised I didn't have that at some point.

Gates: Yeah, sounds like that's what you had.

Notaro: Yeah.

Gates: Your third-great- grandfather suffered from tuberculosis, which was also known as consumption.

Notaro: Why the "galloping"?

Gates: Raging, rampant, an aggressive form of tuberculosis.

Notaro: Mmm-hmm.

Gates: Would you like to know what he did in, during the war?

Notaro: Mmm-hmm.

Gates: Records reveal that what Aristide did was fight, repeatedly.

He served in at least ten battles throughout Virginia and what's now West Virginia.

Some of the most fiercely contested territory of the entire Civil War.

The Ps, see those Ps?

Notaro: Yep.

Gates: That indicates that your ancestor was present for that battle.

And you can see on that map which we made for you, which shows everywhere your ancestor fought.

Notaro: A lot of galloping, I imagine.

Gates: Yeah, indeed.

What's it like to see that?

Notaro: It's really something.

It, I mean, it's so long ago, but so recent in history.

Gates: Yeah.

Notaro: Wow.

Gates: And you had no idea.

Notaro: No.

No, this is all a surprise.

Gates: Aristide was fortunate to have survived so much combat.

But his luck didn't hold.

In the autumn of 1864, he was captured and sent to a Union prison in Maryland known as "Point Lookout."

Conditions were abysmal.

Inadequate food, prisoners reported eating rats, and even seagulls.

Notaro: Oh, not seagulls.

Gates: Typhoid fever, smallpox, dysentery, and malaria were commonplace.

Notaro: Ugh.

Gates: How does it feel knowing that your ancestor fought in so many battles, fought for the Confederacy, was a prisoner of war?

Notaro: I mean, it sounds miserable, frankly.

Everything that's happening, and what they're fighting for, and... Gates: Oh yeah.

Notaro: The abuse they're putting themselves through to fight for something that's just, like, "What are you doing?"

You know what I mean?

Gates: Sure.

Notaro: And it's just like, it's, it's, it's like, "Eh, you should've taken a different route."

Gates: Aristide returned from prison a sick man, he would be dead within a decade, leaving his family in dire financial straits.

In her pension application, his widow, Tig's third great-grandmother, claimed to be impoverished.

Surveying their story, Tig found herself struck once more by the dramatic difference between her experience and the experiences of her ancestors.

Notaro: Well, it makes me feel very aware of how, truly great and charmed my life is, and with that, I think of, again, all of my family, that made my life possible and happen, and there were some hard roads, and I think I just feel really grateful for this experience, and for my life, and uh, for their lives, and everything that's led me right here to this table.

Gates: The paper trail had now run out for all three of my guests.

It was time to see what we could learn from their DNA.

Each was in for a surprise.

When we compared their results to those of other people who have been in the series, we found significant matches, evidence of distant cousins they didn't even know that they had.

Gates: Would you please turn the page?

Notaro: Is it Beyonce?

Gates: You know who that is?

Notaro: Really?

Gates: You are cousins with Gloria Steinem.

Notaro: That is incredible.

Silverman: Really?

No way.

Maggie Gyllenhaal.

Gates: Maggie Gyllenhaal.

Silverman: That's crazy.

Gates: You two share stretches of identical DNA along your chromosomes one, two, nine, and 17.

Silverman: I don't know what that means.

Gates: It means you got, you share DNA!

Silverman: That's insane.

Gates: And if you share long segments of identical DNA.

Meyers: Uh-huh.

Gates: It means you share a common ancestor.

Meyers: Great.

Gates: 'Cause it's not random.

Meyers: I love this.

Gates: Sometimes we strike out, but not in your case.

Meyers: I'm so excited for this.

Gates: You have a DNA cousin.

You want to find out who it is?

Meyers: Yes.

Gates: Please turn the page.

Meyers: Oh, yes.

What a dream come true.

Gates: You share a stretch of identical DNA with Kevin Bacon.

Meyers: Great.

That's great.

This is one degree of Kevin Bacon.

You know what this means.

Gates: I know, yeah.

Meyers: This is the dream.

I don't have to go through any of them.

Gates: No.

Meyers: I don't need "Footloose", I don't need any of them.

Gates: It's hilarious.

That's the end of our journey with Seth, Sarah, and Tig.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots".

Linney: Wow!

Narrator: Next time on "Finding Your Roots" filmmaker, Michael Moore.

Moore: My soul has been touched by this.

Narrator: Actors Chloe Sevigny.

Sevigny: I think my father was very bold.

Narrator: And Laura Linney.

Linney: That's unbelievable.

Narrator: Ancestors who struggled.

Gates: This is the first time that we've seen a white person described as a slave.

NARRATOR: Sacrificed.

Sevigny: Poor girl, from child to bride.

Narrator: But wouldn't quit.

Moore: I'm so afraid to turn the page, just tell me he's going to be okay.

Narrator: On the next "Finding Your Roots".

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S5 Ep7 | 30s | Dr. Gates reveals the histories of comedians Seth Meyers, Tig Notaro and Sarah Silverman. (30s)

Seth Meyers | Meet Mejer Trakianski

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep7 | 29s | Host Henry Louis Gates, Jr. traces the family history of Seth Meyers. (29s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: