Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella

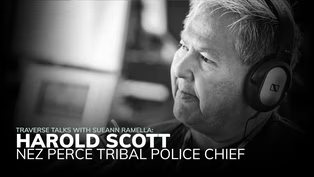

Police Chief Harold Scott

1/8/2022 | 29m 58sVideo has Closed Captions

Nez Perce Tribal Police Chief Harold Scott On Changing The Culture Of Policing.

Chief Scott talks about his childhood in Lapwai, Idaho and how the racism and disrespect placed on him and his community lead him to a career in law enforcement where he hopes to change the culture of policing. Harold has been in law enforcement since 1983 and became the Nez Perce Tribal police chief in 2016.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella is a local public television program presented by NWPB

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella

Police Chief Harold Scott

1/8/2022 | 29m 58sVideo has Closed Captions

Chief Scott talks about his childhood in Lapwai, Idaho and how the racism and disrespect placed on him and his community lead him to a career in law enforcement where he hopes to change the culture of policing. Harold has been in law enforcement since 1983 and became the Nez Perce Tribal police chief in 2016.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(upbeat music) - [Ramella] Imagine playing with your friends outside.

Y'all are jumping up to see who can reach the top of the stop sign.

Then, a police officer pulls up, handcuffs you, and puts you into the patrol car.

Years later, you're protesting for tribal fishing rights in Idaho and you get arrested.

This is what happened to Nez Perce Police Chief, Harold Scott.

Hear why he became a police officer and his thoughts on policing in this episode of "Traverse Talks."

(upbeat music continues) Chief Scott, you grew up in Lapwai.

What was it like growing up in the 60's and 70's?

- [Harold] There was some good times and there was some very educational bad times.

- [Ramella] Tell me about the good times first.

- [Harold] Good time is growing up with a very large family, eight brothers, eight sisters.

We were very close.

Lapwai was very quiet at the time during the daytime.

Then, we had a lot of cultural stuff to take part in.

A lot of sport events that we could participate in.

So it made it kind of nice and the community is people around.

I remember back then, everybody was in the neighborhood.

There were no video games.

So all the people would play together.

And we'd all meet in certain sections in someone's house.

And we'd all play together.

- [Ramella] Yeah.

- [Harold] Totally different than today.

- [Ramella] Yeah, it is.

I was just thinking last night about, I grew up on the air force base and we, we would go inside each other's houses and I don't even remember the parents.

I just remember how we would, we just lived in and out of houses and outdoors at the playground, fed the horses.

And I think even then in the '80s that was starting to disappear in many places.

It's type of freedom.

- [Harold] Yes.

- [Ramella] And what were the challenging times or the educational times when you were growing up?

- [Harold] I think a lot of it was, there was a lot of racism, was very, very bad.

I could tell you back to when I was a youngster myself, growing up, which basically gave me the education to what I am today.

I didn't wanna see people have to experience some of the experiences that I've had, grew up with.

And those things were just basically, a person of color being stopped by officers for walking on the street.

I grew up with very respectful parents.

And they taught you not to vandalize, taught you not do a lot of stuff, you know, that was bad.

It had to be respectful for everybody, no matter who it was, you had to respect them.

And it was very, like I said, a family orientated where, all your family members could discipline you.

Your uncle or your aunties.

So you never wanted to get in trouble, you know.

And having a big family, you basically carried yourself respectfully.

But, when that respect was taken away, by officers who would pull you over just to question you, and accuse you for something that you weren't even a part of, made it pretty rough.

- [Ramella] What did that do to you as a young person inside?

- [Harold] It was very frustrating, very upset and a lot of times.

I remember one particular, one I share with my family is, I mean, my cousin was just walking down the street and we were trying to see who can jump the highest.

And we were jumping up to touch the top of a stop sign and a cop pulled us over and told us we were vandalizing the city property.

And put handcuffs on both of us and put us in a patrol car.

- [Ramella] How old were you?

- [Harold] Maybe 10.

We were just young.

We were like just, playing on the street like any other kid would do.

But those are things that, I can remember those situations.

- [Ramella] I have such an empathetic and imagination.

Imagining my own kids being handcuffed.

How frightening was that for you?

- [Harold] Unfortunately, it became a norm.

- [Ramella] You get used to it or you just expect it to happen then?

- [Harold] After a while you did.

- [Ramella] Also, what did your mom or dad say when that happened to you?

I'm just, I'm sorry, I'm stuck on that vision though of you guys just like goofing off and being kids.

And then next thing you know you have handcuffs, you know?

- [Harold] Oh, unfortunately, the officer told my mother that we were vandalizing.

- [Ramella] Oh.

- [Harold] And my mother was a little upset at us, taking the officer's side.

And back then, unfortunately, when you dealt with law enforcement, you did take their side.

There was no defending yourself.

- [Ramella] No, you just, it's authority.

- [Harold] Yes.

- [Ramella] They know what's right.

- [Harold] Yes.

- [Ramella] So why would you want to become a police officer?

- [Harold] Because of that.

Growing up, and actually during that time too was, you only seen police officers.

And the time you saw him it was never communication.

It was more of you were in trouble.

There wasn't the officers that actually approached people in the community and tried to work with them.

They were pretty much abusive of power during those days.

- [Ramella] So even from the time that you were young, to now you have seen changes in the way policing has been done.

How much more change do you think needs to happen in policing culture or the way that we approach policing?

- [Harold] I think law enforcement officers all need to realize that the people that are policing are just people.

And when we are policing, we are no different.

We are, our job is to maintain a safe environment.

And one of the big things that I teach in my experience, arrest isn't really doing the job.

Arrest is your last resort.

If you can communicate with anybody to resolve a situation, you've done your job.

I felt, growing up that if the officers back then, or you just saw people as people, and we're all not perfect, if we were then the world would be perfect.

And then again, we would have nothing to gripe about.

But, unfortunately, we are who we are.

And because of that, we all think different.

We all have different behaviors.

We all have different cultures.

At the same time, we just need to respect each other's person, in that way.

- [Ramella] Chief Scott, your mother, in the mid to late '70s helped organize a protest to protect native fishing rights, down in Riggins.

You got swept up in that.

And again, wearing handcuffs.

Why was it important to be a part of that protest?

And what was your view of the policing then?

- [Harold] I saw a lot of civil rights violations when we were very young age.

And actually experiencing it.

Knowing that our culture is to basically protect the land, protect everything around it, protect everything that grows around it, to be able to harvest and take those things to share with our life and to share with people who need.

So when it came to fishing, that's something that my family grew up fishing and hunting.

And my mother, she actually, there was an article that came out in the Lewiston Morning Tribune.

That basically came out and said that, state of Idaho called fishing, to Nez Perce tribe.

And my mother was a very vocalist for tribal fishing hunting rights.

Or anything to do with our tribe.

So I remember visiting her that morning.

And just told me and my brother at the time, that we needed to go to Rapid River.

And we need to be peaceful.

But we need to let the state know that they didn't have the right to shut it down.

That a treaty was made between the federal government and the Nez Perce tribe.

And mother wasn't like a violent person, but was very vocal.

So we took it upon ourselves to make contact with a few other fishermen, several other family members and relatives.

A total of 33 of us then made the trek to Riggins.

And confronted with the state.

- [Ramella] They were there waiting for you.

- [Harold] Yes, they were.

- [Ramella] Do you feel like they were prepared to just arrest you?

- [Harold] If we did any violations such as going into the river one day they had basically closed it, yes.

They were man very heavy.

- [Ramella] Do you feel like you made a difference that day?

- [Harold] I might've made some type of a difference.

But at the same time, as you see what's going on today that, it takes a lot more than that to make a difference.

- [Ramella] Yeah.

Speaking of, takes a lot to make a difference.

What does the verdict of the Chauvin trial mean for law enforcement?

And what kind of difference do you think it'll make for the culture of policing?

- [Harold] That's something that I try to teach all the time is that we treat everybody as the way we want to be treated.

And that's something I would never want anybody to ever experience.

And I believe the people who have marched and stood up are really making a difference.

Because, we see it on camera.

We see it every day is there is a lot of things that are happening that is probably not right.

And with people standing up and voicing their opinion, to stand up for their rights, I believe is making a big difference.

But I know it's a long road.

It's just not here.

It's still happening mother Earth, where we continue to abuse one another's rights.

- [Ramella] Can you imagine if they had cameras and cell phones when you were a kid?

And if there's video footage of you as a 10 year old being handcuffed and put into a car?

- [Harold] Yeah.

My experience is really my own but I witnessed so many things in my lifetime that I wish I did have video.

I wish I did have recording.

But, then again, I believe today when I talk with my family, and having experienced I have, we are making a little more progress in a better direction.

(tribal music) - [Ramella] This podcast, like so many programs on NWPB is brought to you courtesy of donors.

People who watch and listen to NWPB for thought-provoking programs, like "Traverse Talks."

People who give what they can to pay for current programs.

And the technology for future programs.

You can join them, donate any amount that is right for you at nwpb.org.

Thank you.

(tribal music) What are the major differences between your department's policing philosophy and maybe those of neighboring states or counties?

- [Harold] I don't think there's really any, really totally difference.

I could probably say that we all try to educate one another within the areas that we work in our jurisdictions.

- [Ramella] Oh yeah, so you actually have a program where you teach Nez Perce culture to other police, right?

- [Harold] Yeah, we just started that actually.

We have a program where I'll have an officer who works with other agencies to educate them more so on our culture.

- [Ramella] What are some of the like, top few things that police need to understand about the Nez Perce culture.

- [Harold] One of the things he teaches was, goes back to historic trauma, that a lot of our people have had to deal with.

And also the importance of who we are and importance that we are people of the land.

And because of that, we want to protect everything, again, that grows on it.

Because that's what we feed upon, and everything that exists with it.

Also respecting everything that is around, that line grows.

Also, he teaches basically the agreement between the United States government on the treaty.

And let them know that we do have people who continue to practice those cultural gatherings.

So those things are taught.

- [Ramella] Yeah.

You describe yourself as a community police officer.

What does that mean?

- [Harold] Again like I said at the very beginning, if the officers would understand that people are people.

And they know it's like, person is a chief of police, we try to work with and get to know everybody in the community.

Unfortunately, a lot of law enforcement programs only get to meet the bad guy during a call.

Instead of actually driving up to a person in a neighborhood and visit them and get to know them as a person.

And not as a violator or sometimes as a victim.

But, I share a story with my officers.

I met a neighbor a few years back.

Lived in the same town that I lived in prior.

And he lived there the whole duration that I was a chief at the time, Chief of Police that is.

Anyway, we moved next door to each other.

You know, came from the same town that I left that we worked in, never knew each other.

And I told him, I said, that's the sad part, is that, unfortunately, I had blinded myself to only know those I had to deal with, instead of knowing the people.

And if I would have probably used more of my concept of knowing everybody, I probably would have got to know you before I had to meet you here 10 years later.

And we came from the same place.

And we just kind of joked about it and laughed about it.

We became pretty good friends at the time.

But I tell officers, I said, we have to work with the community.

We need to work with them.

Because they are very, just another part of law enforcement than anybody is.

You work with them, they'll help you.

And our job is the same.

We all got to maintain safety.

We all got to take care of the people who reside and live or visit in those areas.

And as long as we communicate with them, can make a place a lot better.

- [Ramella] So they can trust you and come to you when there's something that they need help with, instead of being afraid.

- [Harold] Trust and respect is a really big thing.

- [Ramella] How does a Nez Perce man get or feel trust and respect in a country that hasn't given you that?

- [Harold] Very interesting question.

One of the big things back in the day was, you kept quiet.

You didn't say anything.

Just to be, you know, be quiet.

And during the racism time you hid your color.

Because that's the reason why you were stopped on the road because of you're a person of color.

Or you were judged because you were a person of color.

I have spoke on many occasions that, be who you are.

Don't be something else, be who you are.

Be proud of your culture, your heritage, your beliefs, your people's beliefs, your own (indistinct).

And educate people who you are.

'Cause they'll never know who you are.

They can't walk into your house and judge you until they actually know you.

And that's the same thing as we have to do the same with anybody else.

You know, I truly believe whoever said, you know, walking into someone else's shoes, big difference.

And so I kind of lived that.

- [Ramella] Yeah.

When it comes to guns and gun safety, what are some things people need to understand?

- [Harold] My last tenure is cheap I didn't carry a weapon.

- [Ramella] Really?

- [Harold] I carried a pair of handcuffs.

And that's all I ever carried.

Because of the way things have changed today.

Unfortunately, innocent people are being attacked for, again, because of skin color, because of things that are happening.

I carry a lot for the protection of the people, to make sure that if it was anything to happen that I would be able to protect those people who cannot protect themselves.

So Perce weapon goes, our program trains on it.

Again, it comes down to like the arrest, weapon is your last resort.

We've had, since I've been chief in 2016 to present, we've had over a dozen hostage situations.

Where people had actually held themselves up and did not want to come to law enforcement.

So they barricaded themselves or had somebody with them.

But we were able to negotiate all those incidents without nobody getting hurt.

Again, with the officers that I have work with, I really commend them that they're able to speak and work with the people.

And again, a lot of it comes back to community policing.

They actually knew the people and were able to understand the person.

And I just don't wanna see anybody ever, no matter who it is, whether it's a bad person or not, we don't have to take a life or anything.

That's one of the big things that people understand in law enforcement is that, taking a life, not only does the family have to deal with it, but the officer involved has to live with that.

And that's something we never want to ever see.

- [Ramella] I mean, there's quite a lot of tragedies and these accidental murders and deaths.

And I don't think we've had the conversation of what it is like to kill somebody.

I mean, if anybody's ever hunted, that spiritual feeling of seeing the life go out, and that's an animal, what is it like when it's a human being?

Is intense.

So Chief Scott would you say then you would prefer not to carry a weapon with you when you're policing?

- [Harold] I could tell you back in my last tenure, that I felt more safe then.

But today, no.

Today because, every day you seeing a shooting.

Every day, somebody is doing something to somebody else.

Today, because of color, people are being shot at.

And unfortunately, I guess this comes down to, we have to be able, as law enforcement protect those who cannot protect themselves.

- [Ramella] You can always have NWPB in your pocket by downloading our free mobile app.

Just search for NWPB wherever you get your apps, you can listen to us anywhere.

What is your advice to people who are outside of law enforcement, who want to see police cultural change?

- [Harold] I think like anything else, again, just like we do have a program in our program.

It's a rider's program.

And where you can actually sign up and ride with an officer.

And I think a lot of it is, a lot of people don't understand the toll function of a police officer till you actually get in a car to ride with them.

And it's a lot, again, like I used to always say, since I grew up on the other side, and became a police officer, and grew up through the ranks to become a leader in law enforcement, that anybody can call it behind the desk.

But in the actual situation, it's a lot tougher when it's face to face.

And I believe that people will learn our job more if we have that type of a more of a community policing.

People can work together and see the real functions.

Law enforcement has to make split second decisions, in this top (indistinct).

And yes, we are people.

Yes we do make mistakes.

But at the same time I do know that our teaching, is trying to eliminate those mistakes.

- [Ramella] There's the BLM movement.

And simultaneously what bubbled up is, police lives matter movement.

What are your thoughts on that?

- [Harold] Well, unfortunately, policing right now is, even as a police officer it's a very tough position.

Because, I've always said no matter, before this ever happened, I've always said police officers or anybody held in a high position, administrative wise or government position or local state government, however you wanna put it, that we live in a glass house.

And as glass houses is what we do, is what we dictate the people will watch.

And if we want that respect then we need to carry ourselves in a very professional manner.

And it goes for anybody.

And I really believe that, we wouldn't have to worry about Black Lives Matter if we just treated people the way people are.

We wouldn't be in this position.

But we have to work together.

- [Ramella] Just to see each other as people.

- [Harold] Yes.

- [Ramella] Or to see people with more melanin as people.

- [Harold] Yes.

- [Ramella] Yeah.

How would you say the community perceives you?

Like what do you think your reputation is?

- [Harold] I hope, good.

But, it's a tough job.

It's a very tough job.

All I can do is say that, no matter what, I respect them.

They have every right to voice their opinion.

And that's the way that I learn, they have every right to criticize.

That's the way I learn.

It's kind of like getting grades in school.

If I'm getting an F I need to bring it up.

But that's how I look at it.

I really believe that people have that right.

- [Ramella] So now, as a wise, older police chief, when you think back to that officer that handcuffed you when you were 10, what do you understand about him?

- [Harold] I understand that, now it's my turn to teach them.

So those kinds of things don't happen.

And that's the reason why I became a police officer.

So I could represent those who were victimized in those kind of situations.

- [Ramella] So this is a, perhaps difficult question, but, before the pandemic hit, there was lots of news about missing indigenous women, murdered and missing.

Does Nez Perce tribe also have this issue?

- [Harold] Right now, we've had a couple we had to experience.

But, right now we have no one actively, on our roster at this time.

But, it's not that we're, we meet on it all the time.

We're preparing for it just in case.

Yes, it's a very sensitive situation because it is happening.

And we pray for the tribes that are going through that.

- [Ramella] Chief Scott, why do you think that is happening?

- [Harold] Well, honestly, I noticed that because of the pandemic and everything else going, we've seen a lot more of those kind of situations happen.

But our people, at times, it may have happen more so, but now it's being more reported, more recorded at this time too.

And again, growing up in a time that we were growing up, and being kind of isolated to the point of our life where, people didn't want to report stuff like that.

Because, outside society had made it to the point where people were embarrassed or felt ridiculed for that kind of stuff.

And didn't wanna put that kind of stuff out.

So I believe today that, we have become more boisterous.

And we're learning a lot more to be more conscious to reporting.

- [Ramella] This is interesting because I feel there's parallel with the Asian-American community.

There's a shame in reporting bad things.

And you don't wanna bring that attention to your family.

But, recently, I think they're done.

They're speaking out more.

There's this perception that getting to know contacts in with indigenous people is difficult.

So like journalists who want to help tell stories or at least do reporting on tribal news, they say that it's not so easy.

Because, well, and we, the rumor is because why should the indigenous folks trust an outsider anyway?

What do you think about that?

- [Harold] I actually really understand that.

Because of, you know, there has been some media output that's been turned around.

And when it turned around and it gives a person, doesn't matter what color they come from, the trust is a big thing.

And when we miscommunicate, that hurts a person.

And I just think a lot of people have a hard time speaking to people they don't know.

- [Ramella] Well, and I feel as if there's a culture of comfort, from totally speaking as a white person.

(chuckles softly) Where when you know that you could be disrespectful or you could say something really offensive, it becomes, you know, you become weird and stupid about it.

And so, learning to be comfortable with not knowing and being uncomfortable and putting yourself in a situation in order to open yourself up to that, I want to know you, but I think we're gonna fuck this up.

(laughs hard) But I'm being honest with you.

(laughs hard) I might ask some really dumb questions.

Please tell me that that was stupid so I could learn with you.

But, I also, there's this other thought that, other people that you're getting to know from different cultures it's not their job to educate you.

So it's just interesting dance, as we try to understand one another.

When we move around each other to find out where we're comfortable enough to open and explore each other and be vulnerable.

Yet, all the while knowing the dominant culture has always made the rules.

And so, how do you unlearn those rules?

So I wanna thank you for your time.

And for answering some pretty difficult questions about policing.

And what I took away is really, about respect and seeing the other as human.

And that's where we should all start with each other.

That's kind of the theme of this podcast anyway is getting to know each other on a human basis.

(laughs hard) - [Harold] Thank you for having me here.

And having an opportunity to, again, speak on behalf of law enforcement, but at the same time speak on the Nez Perce tribe.

But, always remember that, the big thing is just, being respectful for all.

You know, it doesn't matter.

We're all human beings.

And we're all given a short time here on mother Earth.

And we all need to respect it, in that good way.

- [Ramella] Amen.

(upbeat music) That's Nez Perce Police Chief, Harold Scott.

Thank you so much for listening to this conversation.

And if you have questions, comments, or you wanna suggest a potential future guest, you can get in touch, email info@nwpb.org.

Or reach us through our website, Nwpb.org.

Thanks for listening to "Traverse Talks."

I'm Sueann Ramella.

Police Chief Harold Scott - Conversation Highlights

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 1/8/2022 | 3m 45s | Conversation highlights with Nez Perce Tribal police chief Harold Scott. (3m 45s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Traverse Talks with Sueann Ramella is a local public television program presented by NWPB