VPM News Focal Point

Racial Identity | March 21, 2024

Season 3 Episode 5 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

What is the connection between race and identity?

What is the connection between race and identity? How many Virginians consider themselves racially or ethnically diverse? We’ll examine how DNA testing has changed our perceptions of identity and learn about Black maternal health disparities.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown

VPM News Focal Point

Racial Identity | March 21, 2024

Season 3 Episode 5 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

What is the connection between race and identity? How many Virginians consider themselves racially or ethnically diverse? We’ll examine how DNA testing has changed our perceptions of identity and learn about Black maternal health disparities.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMADDOX OWENS: I am called monkey, niglet, n-word, slave, cotton-picker almost daily.

I want to feel safe when I go to school.

This shouldn't be happening in 2024.

Thank you.

(applause) ANGIE MILES: You just heard a comment from a student in Powhatan, Virginia, where conflict over race has become a flashpoint in the schools in recent weeks.

Racial division and confrontation can be fueled by a lack of concern for others and by a lack of understanding.

Today, we consider where we stand when it comes to race.

VPM News Focal Point is next.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪ ANGIE MILES: You're watching VPM News Focal Point.

I'm Angie Miles.

At a recent school board meeting in Powhatan County, an overflow crowd of public speakers addressed both racial and LGBTQ issues forcefully, saying the school board and administrators must do more to increase understanding of differences and to protect students from race-based harassment.

Dale Goodman was one of the students who helped integrate Powhatan schools more than 50 years ago.

DALE GOODMAN: Back in the sixties my parents had to teach me how to tolerate and cope with the name calling and racism as I entered the school building each day with nothing but fear.

Not just for me, but fear also for my parents.

Hatred and racism was in the past.

It is here now in the present, and we know that it is not going away.

ANGIE MILES: While we're not focusing on Powhatan in this episode, we are talking about issues of race and how history and social norms inform who we are deep down and have a major impact on how we do or don't get along.

When it comes to public art, public health, scientific and social breakthroughs, let's reflect together on the realities of race.

Over the past several years, Virginians have made sweeping changes, removing tributes to leaders of the Confederacy from public spaces, and in their place is art intended to be more reflective of a diverse population.

Producer Adrienne McGibbon takes us to an artist's studio for an early look at a statue that depicts the stirring story of a determined school girl.

(soft music) STEVEN WEITZMAN: If you read the story about Barbara Johns, it's extraordinary.

It's so heroic.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: Artist Steven Weitzman is putting the finishing touches on a statue of Barbara Johns.

She was 16 and attending the segregated Moton High School in Farmville when she decided to take a stand.

STEVEN WEITZMAN: And here you had a young lady that just was just fed up with the inequities of the school system and promises made, but not kept.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: In 1951, she gathered 400 classmates into their school auditorium and called for a walkout.

STEVEN WEITZMAN: And the story is what created the design, or the concept behind this sculpture.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: Once completed, this statue is destined for the U.S. Capitol.

Barbara Johns will be one of two people representing Virginia in Statuary Hall, replacing a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

Johns died in 1991.

Recently, her sister, Joan, shared her family story with a group of Virginia teachers.

(audience applauds) JOAN JOHNS COBBS: I thought that the white community would try to harm us, and I was worried that our parents would discipline us too.

They were shocked, but in some ways they weren't so surprised because they knew Barbara was outspoken.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: For her safety.

Johns finished high school with family in Alabama.

She went on to attend Spelman College, married, had five children, and worked as a librarian.

117 students at Moton joined as plaintiffs in the US Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, which ended racial segregation in schools.

JULIE LANGAN: It was easy to reach consensus.

ADRIENNE McGIBBON: Julie Langan was part of the commission that decided to put Johns in Statuary Hall.

JULIE LANGAN: The commission was looking for a subject that really represents Virginia today.

JOAN JOHNS COBBS: And I think the fact that they chose her was one way they're trying to rectify what happened in the past.

ANGIE MILES: The statue of Barbara Johns could be installed in the U.S. Capitol as soon as next year.

The Robert E. Lee statue that was removed is now on display at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond.

ANGIE MILES: We hear people talk about an idealized post-racial society where the color of one's skin doesn't matter at all, but is that optimal?

We asked people of Virginia, "Is race an important part of personal identity?"

FAYSAL SCOTT SMILE II: I think it's pretty important.

A lot of people like to know where they came from and it's good to look back and see your heritage, see where your people were thousands of years ago, you know?

SUMMER MATHIS: And I'm thinking like, 'Let's get down to the science to it.'

If you were in a hospital right now, you would need to know your racial identity to get proper medical treatment.

So it's, like, yeah, I would say that would be super important, right?

TY BROWN: Well, I would say it's pretty important, which is concerning, considering a person's character is more important than their identity.

AMARIE BUTLER: I think that it's very important.

I mean, I feel like it's how we kind of express ourselves as people, and so when we think about, "Okay, how do we think about ourselves?"

I feel like a lot of that kind of comes from our culture.

ANGIE MILES: Black women in America are three times more likely to die from a from a pregnancy-related cause than are white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Special Correspondent Dennis Ting spoke with a team of medical experts in Norfolk working to address those dangerous disparities.

DENNIS TING: It was supposed to be a joyful time for Allison Moore, a Virginia woman learning she would become a mother to a baby girl named Peyton.

ALLISON MOORE: I found out on Christmas day of 2021.

DENNIS TING: But 20 weeks into her pregnancy, Allison felt something wasn't right.

ALLISON MOORE: And the next thing I know, I hear whoosh.

DENNIS TING: Allison was rushed to Eastern Virginia Medical School.

After several days in the hospital, the expectant mother realized something was wrong.

ALLISON MOORE: And when the nurse came in, she was looking for her, I said, 'She's gone.'

And about 10 minutes after that, I became sick.

DENNIS TING: Allison's story is not unique.

In the United States, Black women face significantly higher rates of health complications and death during pregnancy and childbirth when compared to white women.

And most of these maternal deaths are preventable.

LINDSAY ROBBINS: Those numbers show that Black women die about 2.5, 2.6 times higher than white women.

DENNIS TING: It's a problem close to Dr. Lindsay Robbins' heart, who has treated many Black women through their pregnancies, including Allison.

LINDSAY ROBBINS: I have to remember those statistics, even though it feels like it's not happening to this person in front of me, I know that it could.

DENNIS TING: Dr. Robbins is the director of the Center for Maternal and Child Health Equity and Advocacy at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

The center's goal is to eliminate these disparities by researching the causes and finding solutions to this complex problem.

LINDSAY ROBBINS: When we look at a health outcome, there's of course the patient and there's the medical team, but there's also the community and the societal structures.

DENNIS TING: The center, founded two years ago, uses data to better understand the problem of disparities in Black maternal health, and to advocate for better policies and guidelines.

GLORIA TOO: Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of maternal mortality in the United States, and it's overrepresented in our Black patients, unfortunately.

So here we are working really closely with our cardiology colleagues, our anesthesia colleagues, as well as the hospital to provide comprehensive care during pregnancy, during delivery itself, and making sure we have a comprehensive plan for monitoring afterwards.

DENNIS TING: Dr. Gloria Too and Dr. Robbins both work to address these issues.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says factors that contribute to racial disparities include variation in quality healthcare, underlying chronic conditions, structural racism, and implicit bias.

And this has led to resources being unevenly allocated in the community.

LINDSAY ROBBINS: And the only way to eliminate disparities is to have an even playing field that starts way before the pregnancy even begins.

GLORIA TOO: We have a challenging population because we have a lot of patients who don't have healthcare coming into pregnancy.

We're diagnosing things like chronic hypertension, diabetes, sometimes even things like structural heart issues.

DENNIS TING: For Allison, she says her experience with her miscarriage taught her lessons about advocating for herself.

Lessons that became very important when she learned she was pregnant once again, just 10 months later.

And when she started having complications once again at 20 weeks.

ALLISON MOORE: It was like we were reliving a nightmare for a second.

LINDSAY ROBBINS: And look at your little fancy UGGs.

DENNIS TING: This time, Allison and her doctors at EVMS were able to deliver her daughter Sidney, three-and-a-half months premature.

ALLISON MOORE: Are you losing everything?

You're losing your shoes.

DENNIS TING: Now, six months later, Allison says baby Sidney is doing well.

She wants to share her story, to send a message to other Black women.

ALLISON MOORE: Don't hope.

Always advocate for yourself.

Always stand up for yourself.

If you come across as the angry Black woman, it's your body, you have to.

This is your child.

You have to.

DENNIS TING: While the disparities in Black maternal health continue to be troubling and frustrating, Dr. Robbins says she is optimistic about the increased focus on this problem, and that patients like Allison are being more active in advocating for themselves.

LINDSAY ROBBINS: What brings me the greatest joy is talking to patients and learning more about them, and then seeing their joy at the end of a pregnancy that they've worked really hard for.

DENNIS TING: For VPM News, I'm Dennis Ting.

ANGIE MILES: The Eastern Virginia Medical School is also focused on community outreach.

For example, it's hosting baby showers for expectant mothers in the Norfolk area to connect them with resources and share information about maternal health.

ANGIE MILES: VPM News Focal Point is interested in the points of view of Virginians.

To hear more from your Virginia neighbors, and to share your own thoughts and story ideas, find us online at vpm.org/focalpoint.

ANGIE MILES: Do genetics determine racial identity?

Does a DNA test change who we feel we are?

These are relevant questions in an age of home DNA testing.

As these kits have become increasingly popular, many white Americans are discovering the presence of African ancestry in their family trees.

Next one woman shares her story and how she's embracing what she's found in her DNA results.

For this report, we turn to Multimedia Reporter Keyris Manzanares.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Lindsay Webster grew up in Fauquier County and lives at her family's farm.

LINDSAY WEBSTER: Come on!

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: She's a nurse practitioner who spends her free time with her husband caring for their French bulldogs and feeding her peacocks.

LINDSAY WEBSTER: Peter!

Peter's the pretty one.

Beautiful.

LINDSAY WEBSTER: Schools, of course, had integrated in the, I believe, late '60s, early '70s around here.

I went to school with, you know, different races at a certain age.

I went to Remington Baptist Church for perfect attendance for Sunday school, and I learned every Sunday, "Love all the children of the world."

Red, black, yellow, white, you know?

There's a whole song about it.

And then during the week, you don't hear always the kindest things about people of another color from the same Christians who teach you that on Sunday.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Webster says she always felt different than others in her tight-knit community, and didn't understand why people around her couldn't see beyond race.

LINDSAY WEBSTER: I am a white girl.

That's who I am, right?

I'm blonde hair, actually, I was born with brown hair and it turned blonde by the time I was a year.

I do not tan at all.

When I tell you I have no melanin, I have none.

I glow in the dark.

I'm white, (laughs) pale white.

And so I saw myself as that.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Turns out, Webster's family lineage can be traced to a man named John Punch.

LINDSAY WEBSTER: He was born 1605 in Angola, and he had one son in 1630.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Who's considered to be the first enslaved African in the colonies that formed America.

LINDSAY WEBSTER: I am white.

I'm white.

I don't think of myself as anything other than that, but there's 1% of me that is not, which means my mom has a higher percentage, my grandmother had a higher percentage.

The other generations had a higher percentage.

And if the mindset of people in this country hadn't changed from that one drop law, where would our lives have been?

How would things have been different for us?

I think it speaks to the ignorance of that time, but I think it also speaks to the issues of today.

It just feels like there's that connection there, that kind of, I inside of me knew that there was a connection.

My son's biracial.

I teased him.

'You're not the first biracial kid in this family by about 400 years, son, sorry to bust your bubble.'

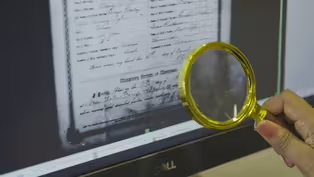

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Webster's AncestryDNA results show that her 1% comes from Southern Bantu Peoples, which can be traced to Sub-Saharan Africa.

MICHELLE TAYLOR: When you do a DNA test, often when I am, people say, “Oh, I'm X amount African, X amount European.

” Well, Africa is a really large continent.

So the Sub-Saharan region that appears is very much connected to the slave trade.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Michelle Taylor specializes in African American genealogy.

(tape whirring) She often travels to the Library of Virginia for research as she builds family trees for her clients.

MICHELLE TAYLOR: I think that DNA tests definitely can challenge racial identity because you're looking at things in a new lens.

You go in taking the test with an identity you've already assumed, and now you have a test that is telling you maybe something a little different than what you had already went in thinking you knew.

ASHLEY RAMEY CRAIG: I would say you hear a lot that all roads lead through Virginia.

A lot of people can either pinpoint an ancestor stepping on Virginia soil for a period of time, or they spend centuries here.

So we have everything, sometimes everything in one location.

That can be county records, state records, bible records that you might have to go to many other institutions to look for.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Ashley Ramey Craig is a community engagement and partnership specialist for the Library of Virginia.

From March through October, the library hosts a series of genealogy workshops for those building or digging into their family tree.

ASHLEY RAMEY CRAIG: So we start off on a beginner genealogy workshop that will give you information of where to look, which records you should use, which records youll find more information in.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Shawn Utsey, a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, is teaching his students about racial identity this semester.

During class, they learned about Utsey's complex family tree.

SHAWN UTSEY: Now Martha Graham, my great-great-grandmother, was born in 1841.

This is one of her sons.

Obviously, she was not married to a white man.

Likelihood is that this is the product of a rape or other form of coercion.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: A 2014 genetic study revealed that on average, the African American genome is 73.2% African, 24% European, and 0.8 Native American.

SHAWN UTSEY: Living in a racially conscious society requires all of us to create narratives that explain who we are, right?

And so we typically think about America, the institution of slavery and how it's impacted Black folks, but white folks were also impacted by the institution in ways that we've not yet discovered.

And so all of us in relation to that institution, that common history, construct narratives that explain who you are in relation to that.

We want to talk about the complexity of Black identity for people who perhaps are or are not biracial, right?

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: Utsey says that DNA is a truth teller, and that more white Americans than we think could have African ancestry.

STUDENT 1: There was not really a lot of information.

SHAWN UTSEY: Tell me when your family began to contemplate the possibility of African ancestry, what was that?

Was that shocking to you all or did it make sense historically?

What was your reaction?

So there's no real scientific process by which we arrived at racial groups, but we have agreed on the racial groups.

And so we have rules around who fits in what group.

And obviously the “one drop rule ” suggests that anybody with one drop of African ancestry is Black, regardless of how they look.

Even in slavery, when people began to pass and not return, right?

Those who passed and became white and continue to be white, and are white today, they are discovering that ancestry.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Webster says her DNA results don't change how she views her race, but instead bring to light her 1% of African blood.

LINDSAY WEBSTER: I think it's about acceptance, you know?

And just knowing where you're from.

It may not mean anything to someone else who wants to deny it.

It may not mean something to someone else who feels like it's such a minute percent, but to me, it meant the world.

I love it here, it's beautiful.

It's a place of peace for me.

KEYRIS MANZANZARES: For VPM News, I'm Keyris Manzanares.

ANGIE MILES: Lindsay Webster says she's looking through more than 40,000 matches on her mother's side, hoping to find cousins who also descend from John Punch or the Southern Bantu people.

Incidentally, another person with ties to John Punch is Former President Barack Obama.

He is also likely descended from the first enslaved American through his white mother's family line.

ANGIE MILES: The problems with race in Powhatan have captured headlines throughout the region and the problems are, unfortunately, longstanding.

I am as aware of this as a person can be, having myself grown up in Powhatan, attended schools there, and maintained lifelong relationships with diverse Powhatan classmates, educators, and some administrators as well.

I went to my hometown this week to talk through some of these issues with those who have the most at stake in this race-related impasse, and here's one of those conversations.

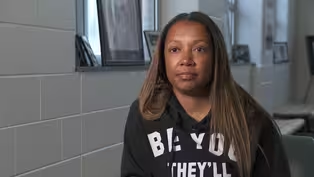

ANGIE MILES: I'm here with Deone Allen who has children who attend Powhatan County schools and they've been attending for several years.

Thank you for being with us today.

DEONE ALLEN: Thank you.

ANGIE MILES: So what compelled you to go before the School Board?

DEONE ALLEN: I wanted them to know what we've experienced.

My son has been told that his hair looks like jungle vines.

He has dreadlocks.

He's been told his hair is weird.

It's dirty.

It's ugly.

Why do you wear your hair like that?

Nobody wears their hair like that.

But the n-word with both the -er and the -a at the end, he's been called.

ANGIE MILES: And what do you want to see the school, the administration, the board do in response?

DEONE ALLEN: I think that every incident should be raised.

It should not be tolerated, because too many times thats happened.

And then as far as...

I would just want administration to enforce the rules.

Protect the kids, that's what the rules are there for.

All the kids.

Even if it's a biracial child or LGBTQ child like protect the kids, they should feel safe at school.

They should not have to come and deal with that.

Mentally it interferes with their education.

That's my other concern.

So educate, respect the boundaries and the protection of those students and move on.

(upbeat music) ANGIE MILES: You can watch the full interview on our website.

ANGIE MILES: The Daughters of the American Revolution honors the men and women who fought for independence from the British.

The women of the DAR are tracking down Forgotten Patriots and their descendants in an attempt to acknowledge the efforts of Black and Indigenous patriots.

Producer Adrienne McGibbon spoke with some of the organization's newest members.

SHERYL SIMS: I'm a quilt artist, and this quilt I really love, because this is a quilt of my fourth great-grandfather's plantation house where he had enslaved my fourth great-grandmother.

And the majority of my quilts are actually about family members and ancestors, and things like that.

I descend from Andrew Cox, basically through my fourth great-grandmother's daughter.

She had two children by my fourth great-grandfather to whom she was enslaved.

I became a member of DAR officially in 2022.

It meant a lot to all of us, because I was the first member of color to get into the chapter.

It's very difficult, and then to find documentation you have to prove through records that you have a connection to each generation.

For me, it was a little bit frustrating, because some of that we know, you know, as people of color, like we know the nature of slavery.

But when you're in a lineage society and not just DAR, others as well, you have to prove these things.

PAMELA WRIGHT: Our administration has set as one of our goals in the beginning to promote a sense of belonging for all of our members.

And when our members feel like they belong to our organization and have a place, they bring their diversity.

And by combining our diversity of experience, we are a stronger organization.

Often research is very difficult for African American women, because documents are present up until about the Civil War time, but back of that due to slavery, it's hard to prove ancestry.

But with the different resources that are available online now all avenues are opening up and the DAR is proud to collaborate with several organizations that are researching new resources for women of color.

I believe that all patriots should be recognized, but more important, that all women who are eligible to join the DAR are given the chance to research their family and have the opportunity to join us in our service to our nation.

JOHNETTE GORDON-WEAVER: There's an African word called sankofa, which means run back and fetch it.

We've run back and fetched Anthony Roberts and his story, which is a part of my story, the tapestry of my life, if you will.

He makes up that fabric.

I am the first Black member of the Williamsburg Chapter of DAR.

Being a part of DAR means that someone recognizes the work that my patriot did.

The history and the story that goes with it.

He was free already, but people who look like him were not.

And the fact that we have gone back and gotten the story that wasn't being told anywhere, excites and amazes me and makes me want other people to go and find their patriots and recognize and remember them.

We're more American than we are anything.

No matter if you come from the hills of West Virginia, the beaches of California, down in Florida, or my beloved Virginia, we are more alike than we are different.

ANGIE MILES: Thank you for taking the time to contemplate matters of race with us.

Let us know if and how our stories have affected your thoughts.

On our website, vpm.org/focalpoint, you'll find more coverage of the racial challenges confronting Powhatan public schools as the community strives for solutions.

There, you'll also find an interview about Melungeon heritage, focusing on a community of mixed race people with intriguing origins.

We're always pleased to have you as a viewer and we invite you to offer your story ideas and to join us again next time.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep5 | 10m 52s | Deone Allen calls for the School Board to take action to remedy children being mistreated. (10m 52s)

Civil Rights Figure Gets a Step Closer to the U.S. Capitol

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep5 | 2m 12s | Teenage civil rights figure is one step closer to her place in the U.S. Capitol. (2m 12s)

Combatting Black maternal health disparities

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep5 | 4m 27s | Doctors at Eastern Virginia Medical School focus on improving Black maternal health care. (4m 27s)

Diversity is top priority for new DAR leadership

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep5 | 3m 19s | DAR makes diversity a top priority as chapters welcome descendants of “Forgotten Patriots. (3m 19s)

Exploring what it means to be Melungeon

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep5 | 6m 57s | Melungeons are an ethnic group of mixed ancestry with roots in Appalachia. (6m 57s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep5 | 7m 30s | With the help of at-home DNA tests, many are discovering stories hidden in their ancestry. (7m 30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown