VPM News Focal Point

Real life impacts of an invisible disability

Clip: Season 3 Episode 3 | 7m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

A traumatic brain injury survivor shares his experience of living with a disability.

A Harrisonburg teacher, husband and father suffered a traumatic brain injury after a sudden illness. He explains how it changed his life and what it’s like to live with an invisible disability.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown

VPM News Focal Point

Real life impacts of an invisible disability

Clip: Season 3 Episode 3 | 7m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

A Harrisonburg teacher, husband and father suffered a traumatic brain injury after a sudden illness. He explains how it changed his life and what it’s like to live with an invisible disability.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANGIE MILES: Nearly 1.5 million Americans sustain a traumatic brain injury or TBI each year.

Often the effects of a TBI are invisible to the naked eye, but can be debilitating.

Joining us now is John Norment, a Harrisonburg resident who is a husband, a father, and was a third grade teacher before a severe illness caused a traumatic brain injury in 2016.

Thank you for joining us, John.

JOHN NORMENT: Thank you for having me.

ANGIE MILES: John, would you mind explaining to us, please, how did you end up with a traumatic brain injury?

About eight years ago, as you said, I was a third grade teacher when I contracted a viral infection, not too dissimilar from the flu, but the virus ended up attacking my heart pretty aggressively.

So much so that I went from being perfectly healthy to suffering complete heart failure in a few days.

And when your heart fails, that causes clots to form in the bloodstream, which caused several large strokes to occur, the largest of which affected my right hemisphere, basically destroying 80% of my right hemisphere.

ANGIE MILES: Oh my goodness.

That certainly is traumatic, not just for the brain.

It sounds traumatic for your entire life.

What were the side effects of that experience and how did they change your experience of life moving forward?

Basically for me, I have severe deficits in my ability to concentrate.

My ability to focus.

My attention span was pretty low.

I was also completely paralyzed the first stage of my recovery.

My brain had to reform connections with every muscle in my body.

I had to relearn how to walk again.

I had to relearn how to talk again, I had to relearn how to read and write.

It also affected the optical nerves.

So like I had lost all peripheral vision to my left.

So to really sum it all up, there was nothing I did not have to relearn how to do.

ANGIE MILES: Okay.

That is an incredible ordeal and clearly you've made remarkable progress to date.

What did you do that actually helped you with that recovery process?

JOHN NORMENT: I think when I was in the hospital, I think what helped me was that I had a little knowledge ahead of time when I was in my early stage of recovering.

I knew enough about how the brain functioned.

I knew enough about things that I knew the brain had the ability to rewire around permanently damaged areas and knowing that fact gave me some hope at the earlier stages of my recovery, even when I was still paralyzed and unable to speak at all, I had this deep belief that I could recover and that hope is what kept me going at the early stages.

ANGIE MILES: Hope and faith not overrated.

Did you feel like yourself, do you feel like yourself now?

JOHN NORMENT: I think the stroke definitely affected not just me cognitively, it affects your emotions and your personality a lot.

Me personally, I am much more emotionally volatile now than I was eight years ago.

It definitely, and it's really hard to separate what is personality and what is an effect of the brain injury.

Like, I'll wake up angry for no apparent reason.

I'm a much more, you know, like I said, emotionally volatile.

Like in the hospital, it was very severe.

It's gotten better over time.

Like in the hospital, I basically had the emotional self-control of a three-year-old child.

So it was pretty severe.

ANGIE MILES: It sounds like alongside the challenges you have maintained a good amount of self-awareness in the process as well.

JOHN NORMENT: Yeah, I'm actually, yeah, I'm actually quite lucky in that regard.

A lot of right hemisphere stroke patients lose that self-awareness of their deficits, and I was very lucky that I did not lose my self-awareness.

So it was actually beneficial in my recovery that I could tell my therapists, 'I need to work on X, Y, and Z' and a lot of my hemisphere stroke victims lose their awareness of their deficits, and it's up to their therapists and their family members to convince them that they have to work on certain things.

That can be a real detriment to their recovery.

ANGIE MILES: So when we are talking about people dealing with disabilities, some are more apparent, right, to the general public than others.

When people look at you, are there any giveaways or are there any signs that will tell them this is a person who's dealing with a disability?

JOHN NORMENT: I think one of the harder things about me, particularly with my stroke, is that at first glance, I can kind of pass off as somebody who does not have any severe disability going on.

What's hard is that I can do a lot of things that other people can do, like in short spurts, like this, I can have this conversation with you now.

What is hidden is how difficult that conversation is for me to have.

A comparison that I give when I talk about this, it's like everyone else is walking on smooth pavement, under a clear blue sky, and I am wading through waist deep mud with thick fog all around me.

I can get to where everyone else is going, but the amount of effort required is like, astronomical.

So.

And that stays hidden a lot.

ANGIE MILES: And unfortunately there are millions of people in your same situation or similar situation.

What is it that you think is necessary for people to receive the consideration and the accommodations that are needed in the work world and just in everyday life?

JOHN NORMENT: I think awareness in general is really strong.

I think what also really helps.

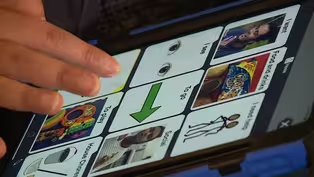

I currently sit on the board of a local agency called Brain Injury Connections of Shenandoah Valley, and we have case managers that work with our clients to provide whatever adaptive technology that they need.

I know that, like I needed adaptive technology because I lost the use of my dominant hand, my left hand from the stroke.

So I think having an expert like a case manager from an agency like Brain Injury Connections in their life to help them find the resources that they need to meet their goals.

That will help out a lot.

We hope that you'll continue to improve and in your process you are also helping other people by serving on this board.

How can people find out more?

it's Brain Injury Connections of the Shenandoah Valley, it's bicsv.org is their website and that's where you can find about them.

Thank you so much, John for joining us.

Thank you for having me.

Deaf and blind students learning to live independently

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 7m 13s | A school for deaf and blind students takes building life skills seriously. (7m 13s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 3m 28s | A community is giving back to a man, who has given much to help others with disabilities. (3m 28s)

Innovations for Neurodivergent Minds

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 5m 45s | New technology is helping people with neurodevelopmental challenges connect with others. (5m 45s)

A nearly 200-year-old haven for deaf and blind students

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 7m 37s | Visit a school that’s been a haven for deaf and blind students for nearly two centuries. (7m 37s)

Wayde Fleming uses the bus from Fulton

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep3 | 1m 53s | Transit advocates are pushing for better accommodations for users with mobility needs. (1m 53s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown