Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story

Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story

Special | 56mVideo has Closed Captions

Cemeteries reflect their community's origins, history, people, and future.

Cemeteries are hallowed places right in our midst. But they also reflect the community, and have evolved dramatically over time, constantly adapting to meet our ever-changing views and values. A cemetery is a mirror of the city: its remarkable origins, its rich history, its complex people, and its unwritten future. A TPT co-production with Lakewood Cemetery.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story is a local public television program presented by TPT

Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story

Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story

Special | 56mVideo has Closed Captions

Cemeteries are hallowed places right in our midst. But they also reflect the community, and have evolved dramatically over time, constantly adapting to meet our ever-changing views and values. A cemetery is a mirror of the city: its remarkable origins, its rich history, its complex people, and its unwritten future. A TPT co-production with Lakewood Cemetery.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story

Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(slow upbeat music) - [Angela Woosley] We spend a lot of our time and energy trying not to think about anyone's death, because it reminds us of our own mortality.

- [Julia Gillis] We're looking for meaning.

I'm going to die someday and what does that mean?

- [Katie Thornton] So often in our grief, we feel alone, despite the fact that death is a universal experience.

- [Kelly Leahy] The way we care for our dead speaks a lot to how we are as a society.

- [Chris Makowske] When somebody dies, what are you going to do with that body?

There's a meaning there.

- [Katie Thornton] So many spaces can be memorial space, but what I think kind of makes a cemetery different is that it's collective.

- [Angela Woosley] Cemeteries are a reminder to the living that we will not be forgotten.

- [Chris Makowske] I think of cemeteries as a bridge between life and death.

- [Angela Woosley] Life.

That is what we commemorate when a person dies.

Knowing that I'm going to die helps me live my life more fully.

- [Julia Gillis] Cemeteries have changed over time in that they reflect the interests and the values of society.

- [Kelly Leahy] The cultural shift that we're seeing right now, just this great re-imagining and questioning of everything.

- [Sydney Beane] Cemeteries should not be in any way, a place of exclusion.

It should be a place of reunification.

- [Paul Aarestad] How do we engage the public and how do we do this and yet still remain to be sacred grounds and still be a place that's reverent and respectful?

- [Katie Thornton] This repository of stories and also of plant life and animal life, you know, right in the city.

- [Peggie Carlson] People drive by, and they have no idea what they're missing.

- [Chris Makowske] If a cemetery is a mirror of the community, if it's a mirror of the people that are within, then it's certainly a mirror of all the change that happens.

- [Sydney Beane] The earth, the trees, the sky, are all connected.

It's all one burial ground.

(Thoughtful music) - Hi, I'm Cathy Wurzer.

We're about to walk through a brief history of what the living do with our bodies when we die here in Minnesota, how cemeteries have evolved over time, and how cemeteries relate to and reflect the communities in which they exist.

While that might sound sad and depressing.

This story is full of life, curiosity, and humanity.

It's also a story about place.

I'm standing in the heart of Minneapolis in Lakewood Cemetery, which has served the needs of this community for 150 years and counting.

And it's not even the oldest cemetery in the area.

Oakland Cemetery in St. Paul is the oldest in the Midwest, Calvary in St. Paul and Pioneers and Soldiers' cemetery here in Minneapolis, also predate Lakewood.

And since those early days, countless beautiful memorial places have been created across Minnesota.

But that's not the beginning of this story.

This part of what is now Minnesota is the homeland of the Dakota people.

And it's been for centuries.

And here, this very spot where Lakewood cemetery now sits, on the Southeastern shores of Bde Maka Ska, was once home to a truly remarkable Dakota village.

(upbeat music) - [Sydney Beane] My Dakota ancestors, particularly Wahpeton and Mdewakanton bands of the Dakota were here for centuries before the non-Dakota people.

And they had their sacred sites and important places heavily related to water.

If you look at the old maps, there are what they call "Indian paths" from Bdote, which is the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi River, which is also where Fort Snelling is located.

From there, out here to Bde Maka Ska, to the falls of St. Anthony, and then from there back to Fort Snelling.

And so if you look at those early maps, that that's how Minneapolis was actually then developed.

This was sort of an apex point along those paths.

And so very significant in that regard that my ancestors then settled to Cloud Man Village, on Bde Maka Ska.

Heyata Othunwe, in the Dakota language was the first year-round village of the Dakota people in the area 'cause people traveled from season to season to place to place.

Because [they] were hunters and gatherers didn't necessarily stay in all one place all the time until Cloud Man Village.

And my great-great-grandfather Cloud Man had been head soldier of Black Dog's Village on the Mississippi, not that far from here.

And he went through a situation in which he almost died in a snow storm.

And at that time, he made a commitment if he survived, to be a man of peace, to take on an experiment of year-round farming.

This is the area also the written Dakota language, came from the Pond Brothers, working with my Dakota ancestors to construct the written Dakota language.

So there's a lot of really important things, Dakota-wise, and city-wise that occurred around this site.

We came from here.

We've always been here.

We've never left here.

'Cause the remains, the bones, the stories of our ancestors are here.

That's what the Dakota worldview is, to live the life as close to nature, within nature as possible.

You can't get any closer than that to the concept of a cemetery or the concept of Cloud Man Village.

(haunting music) - [Chris Makowske] Cemeteries have been with us through most of human history in one fashion or another.

- It's hard to translate a relationship in life to a relationship in death.

And one of the ways that we can do that is having a permanent space to come back to and to revisit our relationship with that person.

So if you imagine for millennia, many societies were placing their dead in a simple grave and burying that person with objects that were important to them and marking it in simple, natural ways that they could come back and identify.

- Our burial customs related, usually, to higher points within an area.

So this area here, which is higher than the lake, would naturally be a place where some of those burials would occur.

And because we didn't have the tools to dig, you know, through winter hard ground, we also very much used scaffolding.

So people were buried according to custom with blankets and robes, and then put on scaffolds or even put in trees to protect them from the animals, you know, until which time they might be then able to bury them within the ground, within a higher area on a hillside.

And so this is an area which is the hillside to Bde Maka Ska.

- If a cemetery is a mirror of the community, if it's a mirror of the people that are within, then it's certainly a mirror of all the change that happens.

- In the 1850s, in what's now the city of Minneapolis, would have really been sort of a remote frontier outpost.

There was a small downtown.

In the 1860s, 1870s St. Anthony, which is now Northeast Minneapolis, and the city of Minneapolis were beginning to grow very, very rapidly.

The first formalized places to bury people emerged out of necessity.

Early white settlers and white colonizers would bury people on private land if they had access to private land, but not everybody did.

The first sort of formal burial space in what's now the city of Minneapolis, is Beltrami Park in Northeast Minneapolis.

So that was previously known as Maple Hill Cemetery.

It was started in 1857.

Pioneers and Soldiers Cemetery in south Minneapolis on Lake and Cedar, was known as Layman's cemetery, which was the last name of the person who owned the land was Layman.

That was somebody's private land, that they sort of offered up for burial, and it ended up becoming a large cemetery, but that was never necessarily the plan.

It is absolutely a wealth of stories, a wealth of information.

1867, the city of Minneapolis was incorporated as a city.

As Minneapolis was growing and becoming more industrialized and more urbanized, there was an increase in population, which also means there was an increase in population of those who were dying.

And these cemeteries that happened out of necessity, didn't necessarily have capacity to hold all of those bodies.

And as they became more and more crowded, it didn't always seem an appropriate place to mourn and to grieve.

(upbeat music) - When Lakewood was founded in 1871, from the beginning, it was meant to be an antithesis to the sort of graveyard of necessity.

You know, in order to really establish itself on the map as a city, Minneapolis should have sort of a grand park-like cemetery.

It was something that a lot of grand east coast cities had.

And so it was both serving a personal and community need, but also kind of a way to put Minneapolis on the map.

Certainly in the US, the civil war was a turning point for how we dealt with death and memory.

Specifically, because it posed a very real logistical problem.

I mean, there were people who were injured and deceased from battle in very, very large numbers.

- The rise of embalming in the Civil War, first of all, it was invented at that time, during the Civil War.

And it took off in popularity largely because they wanted to be able to return their dead to their homes.

And the best way to do that was to chemically preserve them for some period of time.

Embalming was so popular because of the ability and freedom that it afforded time after death and travel after death, that it really did become the norm.

Abraham Lincoln was the first president who was embalmed, and he actually traveled by rail across the country.

People would come to train stations and be able to kind of have a mini-wake or visitation with our fallen president.

The funeral profession started as cabinet makers, creating caskets, and then people in their communities would ask those cabinet makers, could you also take care of the dead?

And so that's where we get the term undertaker.

It was an undertaking that these cabinet makers undertook to care for their communities.

Undertaking became more of a profession and more of a professional responsibility.

That's how undertakers became funeral directors and morticians.

Undertaking led to visitations in the home or wakes.

Funeral directors would go out to a family's home and embalm the person in the home and then lay them out for visitation there.

And eventually people were interested in alternative space to hold those wakes.

And that's how funeral homes and funeral chapels became a thing at all.

We saw the advent of outer burial containers or vaults outside of the casket, using more formalized caskets in general, the inclusion of limestone or granite or bronze markers at the cemetery.

- It's often a emotional and logistical crisis that leads to these changes in memorialization.

In the 1800s, you know, in a city like London-- which was growing very, very, very rapidly with the Industrial Revolution-- those church-side graveyards, which had really been the primary sort of place people were buried for centuries, became really overburdened.

And they were really gristly places.

There was also this now-disproven scientific idea that bad air was responsible for spreading illness and for spreading disease, for spreading, for cholera outbreaks.

And so cemeteries kind of became a focus of scrutiny.

The result was that there was spaces that were created that do a better job of serving both an emotional and a logistical need.

(pastoral music) - It was called the Rural Cemetery Movement.

And it really started in France with Père Lachaise Cemetery, and the idea was that a burial space, a cemetery, shouldn't just serve a logistical purpose.

It shouldn't just be sort of a place for remains.

It should serve an emotional purpose and meet an emotional need.

Rather than being laid out on a grid, there's winding roads and rolling hills and vistas and trees and plants and it kind of doubles as a garden space.

As a city dweller, you should be able to access this sort of park space, what really was in practice, a park space.

- This movement starts happening throughout France and parts of Europe, and eventually crosses over to the United States until you get here to Minneapolis and you finally got Lakewood Cemetery.

This rural or garden cemetery has certain characteristics about it.

Rather than an upright headstone for every person, now you have a large headstone, maybe in the center of a large family lot with smaller stones and a lot of generations surrounding it.

- If you look at the Victorian period, cemetery's needs were different than they are now.

I mean, you lived in the community that you could expect to live and die in and probably for several generations.

And the standards and expectations during the Victorian period was everybody had their own family lot.

You took care of your family.

- A lot of the people who were designing these sort of rural cemeteries, these cemeteries that were accessible to cities, but not right in the city, thought that they were building cemetery spaces that would never be encroached upon by the city.

When Lakeland was started in 1871, the city boundary was Franklin, you know, which is the equivalent of 20th.

So now we're out here at 36th.

I mean, that's quite a journey.

Lakewood was connected to the trolley in, I believe, 1895.

And that really helped increase its accessibility.

To me, as somebody who grew up having this as an urban space, I think it's absolutely a resource that it's surrounded at this point by the city.

(old time piano music) Even with these sort of grand monuments, they were very rarely created specifically for that person.

It was such a sort of trend in the late Victorian era to have these grand monuments, if you could afford them.

But usually they were mass produced.

There was sort of new technologies that allowed tombstones to be mass produced at the time.

You could buy headstones in the Sears catalog.

And if you look through the Sears catalog and you visit any cemetery, sort of from that era, you'll find a lot of those headstones kind of repeated throughout the cemetery.

There were certainly opportunities to sort of engrave and personalize with names, but oftentimes you'll just see, you know, mother, father, daughter.

- Look at all the monuments that we have out on the grounds.

If you saw the size and scales of these monuments, if you think about it for a moment, who erected those?

Those were common workmen that understood and had skills in a block and tackle and a rope.

And they were able to construct these monuments, put 'em up with just those basic items and a horse and a tripod.

The Rocheleau monument, which is our biggest monument.

It's just mammoth in scale.

It's just huge.

It was only maybe three or four men that put that monument together.

It's just mind-boggling.

- In the mid to late 1800s, it was also not uncommon for families to have sort of private mausoleums, which were their own sort of free-standing buildings.

It was much less common to have those really any time after the 1920s, especially after the 1950s.

And because Lakewood is built into a very hilly area, there are some places where those mausoleums are actually just built into the hills, which is an interesting thing to see.

And you'll see that in a lot of cemeteries of the same style across the United States.

(Ragtime music) - In Victorian times, cemeteries were a popular place to gather with the family, maybe on a weekly or a monthly basis.

And people would come out and make a day of it.

You bring out the picnic, the lunch, you gather, and it's kind of like, Hey, we're all back together again.

- When you look at some of the Victorian customs, we would think, well, that's strange.

For example, you know, walking on a grave was really bad taste.

That was about as rude, disrespectful as you could get.

And so when you look at the sections and how it's laid out, you can navigate and walk throughout that whole area on paths.

There's spaces to allow for that.

But today we think nothing of having to walk on graves to get to a new grave or to visit.

- There are some graves that have a death date prior to 1871, which is when Lakewood was started.

So just in this section, there's another grave that says Frances L Bean First Death In Minneapolis, 1838 to 1850.

So Frances Bean, who passed away at only 12 years old had been buried in Maple Hill Cemetery.

By the late 1800s, Maple Hill Cemetery was quite run down.

So it was closed down.

And the city actually mandated that remains were moved from that space.

By that point, Lakewood Cemetery was open.

And so there was actually a number of remains that were transferred from what's now Beltrami Park to Lakewood Cemetery.

Also saying the first death in Minneapolis is quite misleading.

Of course, people had been living and dying and having their memories live on for a long, long time before 1850.

But this is the first white person, the first colonizer to die in Minneapolis.

(quiet slow polka music) - A cemetery's always changing.

It's always evolving.

As we got to the turn of the century, we became a little bit more mobile.

Some of those expectations, you had to have a lot, were loosening up.

When you look at how society changes, those changes happen in a lot of different ways.

They happen in art, they happen in trends, the modernization and mechanization, and building designs.

And those changes are reflected in the landscape.

(quiet, slow polka music) (Big Band music) - Then as you fast forward, and you start to get into maybe the art deco, the early twenties and thirties, and you go through the landscape.

You'll start to see fewer and fewer monuments.

And those monuments are smaller.

And as we progress on that timeline a little bit, we get into what was called the memorial park plan.

And the memorial park plan was probably what we think of cemeteries today.

And that's basically a lawn, with trees, and maybe a monument or a feature in the center.

And those properties were mainly purchased at the end of life, generally in a set of pairs.

(fire crackling) - [Chris Makowske] And then you have cremation comes along and changes some of those options for people.

- [Paul Aarestad] Cremation has been going on for thousands of years, but really the first official mechanized cremation was done in 1882 in Britain.

- [Chris Makowske] Lakewood crematory was actually put in back early in the 1900s.

- [Paul Aarestad] It wasn't used a whole lot.

It was very controversial at the time.

- The cremation rate today is almost 70% in Hennepin County, but then it might've been, I don't know, a half a percent?

Less than that?

- [Chris Makowske] That body is, has been reduced to small fragments.

Now, what do you do with those?

You know, if you've been used to always burying a body, now, how do you handle that?

So the cemetery has to adapt to those kinds of things.

- [Angela Woosley] Cemeteries combine place with commemoration, by way of the types of memorialization that are utilized at the cemetery.

- All the variety that you see within a cemetery, both in terms of the different kinds of burial or interment space that we might have, but the stones, the different colors that you see on people's stones or is it bronze or is it granite?

What kinds of things are inscribed on that?

- It was kind of a slew of industries that cropped up around cemetery spaces.

You saw this at Lakewood, and it's the case at cemeteries across the country as well, but on 36th and Hennepin, there were monument makers, greenhouse for flowers.

- [Paul Aarestad] There were several large greenhouse operations located on 36th.

- [Katie Thornton] 36th street was actually called Greenhouse Row.

- Similar to what they had in St. Paul and Roseville.

There was a whole strip of green houses along there, as well.

And if you look there today, there's Roselawn.

There's a few other cemeteries, all located there.

- Every one of Minnesota cemeteries holds the stories of real people, imperfect human beings, loved by family and friends, important to those they held dear, regardless of fame or fortune.

St. Paul's Oakland Cemetery is a veritable "who's who" of Minnesota's founders and early leaders.

In fact, the namesakes of at least nine of Minnesota's 87 counties are buried there.

It's still an active cemetery today and a popular choice for our thriving Hmong community.

Calvary Cemetery in St. Paul hosts the driving force behind the Cathedral of St. Paul and its architect.

As well as brewing families like Hamm and Schmidt, a Civil War general, even Minnesota's first Black lawyer, Fredrick McGhee.

St. Mary's Cemetery in south Minneapolis opened just two years after Lakewood, it's stunning monuments nestled into this tight-knit neighborhood.

Pioneers and Soldiers is indeed a treasure trove of historic burials, including military veterans from the War of 1812, all the way up to the Spanish American War.

A poignant favorite grave for many is that of Toussaint L'Ouverture Grey, the nine-year-old son of African-American abolitionists Ralph and Emily Grey.

Toussaint is buried with his grandfather, an important leader in the Underground Railroad movement out east.

So many important stories lay in these and countless other cemeteries.

Likewise, some very interesting people are buried here at Lakewood.

- Lakewood in particular, it's got so many different types of monuments, types of people who are here.

You know, everyone from Tiny Tim to Hubert Humphrey.

Everybody is equal in death, and everybody can be here and remembered and honored in the same way.

- When you come to Lakewood, you see that history, you see the sort of ostentatious history.

You see the famous names that you might know from milling, but that also doesn't mean that those are the only stories that live on here, far from it.

I mean, even in the sort of earliest sections with the grandest monuments, you also have the monument that was devoted to the 18 mill workers who were killed in the explosion in 1878.

And on it, there's a gear that is broken.

And anytime in funerary symbolism, when you see a symbol that is broken, it indicates that a life was cut short to soon.

- That's really kind of a lost language.

Those images that are on that monument are telling you a story about that person.

- If you go out to the cemeteries out east and you see what was popular at the time.

Then Boston, there's these kind of angels or faces with little wings.

That was the style, that's on everybody's stone.

- So Maggie Menzel was the first burial at Lakewood Cemetery.

She was buried in 1872.

Her father was a fan of cemeteries.

Whenever he would be traveling, he would always visit cemeteries, which was at the time, a somewhat unusual hobby.

Remains a somewhat unusual hobby.

But he ended up burying his daughter here when she passed away at only 19 years old in 1872, but he also then ended up becoming very involved in Lakewood.

He joined the board of Lakewood and he was buried here himself too.

So the Menzel family monument is right behind us.

And that is the first burial at Lakewood.

(stately music) - There's just an awful lot of history here.

I love to see the politicians.

I've looked at Perpich, Frazier, Humphrey.

- One of the most famous people buried at Lakewood is Hubert Humphrey, civil rights leader, largely credited with helping the Democratic Party adopt a civil rights platform.

He was instrumental in passing the 1965 voting rights amendment.

Very much a hometown hero for a lot of people.

Hubert Humphrey, of course, didn't develop his civil rights platform on his own.

He was massively, massively influenced by Black American leaders in the Twin Cities, from his earliest involvement in politics as mayor of Minneapolis.

And many of those people are buried at Lakewood as well.

(Bluesy music) Lena Olive Smith was the first Black American woman lawyer in the state of Minnesota.

She helped the Lee's stay in their family home in south Minneapolis when their home was surrounded consistently night after night, by a mob of up to 3000 white people trying to push this World War I veteran and his family out of their home that they had purchased in this formerly all white neighborhood in south Minneapolis.

She helped defend that family and helped them stay in their home.

Cecil Newman who founded what's now the Spokesman Recorder, which is still operational, an early, incredibly important influential Black newspaper in south Minneapolis.

Cecil Newman also helped Hubert Humphrey shape his platform and is buried here as well.

- The first Black senator, I think his name is Robert Lewis is in the cemetery.

- B. Robert Lewis was the first Black Senator, State Senator from Minnesota.

He lived in St. Louis Park.

He was, at the time, one of the few Black residents to move into the suburb and he was on the school board and he went on to become the first Black state Senator from Minnesota.

Paul and Sheila Wellstone are buried here as well.

Oftentimes if you visit the grave, there are stones on top of the large Wellstone Memorial.

A Jewish practice where you place a stone on a grave to show that you have been there.

A lot of early Park Board leaders are both buried at Lakewood, but were involved with Lakewood as well.

Lakewood predated the Park Board by 12 years.

And so a lot of the people who went on to sort of shape the parks and shape the sort of recreational experience in Minneapolis started by making Lakewood, essentially a park, a peaceful sort of park for reflection and remembrance.

Two of Minnesota's most famous candy makers buried at Lakewood as well.

Franklin C Mars started Mars, Incorporated.

Mars bar, the Milky Way candy bar.

He is interred in a private mausoleum.

There's another local company, Abdallah Chocolates, the founder is also buried here.

Tiny Tim is also interred in one of the mausoleums here and there are always cards near his memorial dedicated to Tiny Tim and people also leave tulips, in honor of the song "Tiptoe Through the Tulips."

♪ Oh, tiptoe through the window ♪ ♪ By the window, that is where I'll be ♪ ♪ Come tiptoe ♪ - It's great that there's famous people and that's interesting, but I think the everyday people are just as interesting.

- You know how much I miss you (poignant music) - You're my best friend.

My mom was a wonderful mother and wife.

We grew up in Richfield.

We were the first Black family in Richfield.

And she got her degree in journalism.

Always wanted to be a journalist.

And so eventually, she was hired by the St. Paul Pioneer Press and Dispatch.

She was the first Black person to work there.

She went by Mary Jane Samples, but she wrote by Mary Jane Saunders.

And she was there for almost 30 years, I think.

She called the house every single night, swap stories about work because I was the first woman in the state of Minnesota to get a pipefitters license.

And then my mom was having her own difficulties at the paper as a Black woman.

And so we would swap stories about racism or sexism that we were experiencing.

When she died, she didn't have a plot and so the family came together and my husband and I had a spot here and we decided we would give it up for her, so everybody could visit and she's close by most of us.

And it's wonderful.

I come here almost every day, walking.

And I love to say hi to her as I go by.

Then, I had a sister who died with complications of an aneurysm and she's in one of our spots.

And then when his parents died, they took the other one.

So lots of family.

One of my brothers died about five years ago and he's in the new mausoleum.

And then I have another brother who we're going to scatter later on this year in Jo Pond.

And so as I'm walking around, I'm saying hello to family, and check and make certain everything looks good.

Bob, who used to work here, I referred to him as the unofficial archivist.

I asked him if this cemetery, when it opened, did they have a rule against minorities being buried here?

And he said, absolutely not.

(hopeful music) - My family came over from China about the turn of the century.

My great-great grandparents came over as merchants.

And again, like every other family at that time seeking a better place for their family.

- There were a lot of Chinese people in the Minneapolis area.

When somebody died, they used to go back to their homeland in China, which was the custom at the time.

- But because of the war, they couldn't do that and they went and checked several other cemeteries.

And they said, no, because they were Chinese.

But not only did this cemetery welcome them, they gave them a special spot.

It's still there, so.

- This area started out as the Chinese section.

My uncle, who happens to be in the mausoleum, wanted to be close to his aunt, my great aunt.

My mom wanted to be close to her parents, you know.

I've got great uncles and cousins, so we're kind of all over the place, but they're a very large population of the Chinese community is here.

I come here quite a bit.

My parents are recently deceased, within the last five years or so, but I come here when my life is kind of really chaotic, not only visit them and see them, but I come here and just to kind of gain balance.

It's really peaceful.

To know that the history of Lakewood is the same history that sort of follows my family.

You know, it gives you some great comfort.

- My sister wanted to learn more about our ancestors over lunch one day.

So we joined ancestry.com, found out that our great, my sister's and my great-grandparents were buried here.

So we came looking and couldn't find them.

They didn't have gravestones.

So we had to find the people that were buried close to them that did have a grave stone.

So we could find where they were.

My sister and I just felt it was wrong that they didn't have a gravestone.

So we decided to get a stone for them.

And then our cousins wanted to pitch in, too.

So that's where it really all began.

- When the stones came in, we had family members that wanted to gather with us, and we had a little bit of ceremony when they place the stones in the soil and it was very touching, very moving.

- My sister and I and David have gone on to locate all the other relatives scattered around the Twin Cities in different cemeteries.

- It's been our honor to go around to these cemeteries and clean up some of these graves.

It was very difficult to find them.

Grass has grown up over them, clean them up.

And then she ended up making diagrams and maps for all the family, for nieces and nephews, further generations of where they're at and how to find them.

- [Karen Erickson] It's been more than meaningful.

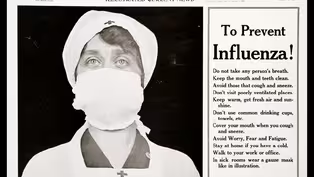

(mournful music) - A lot of the old timers used to talk about the 1918 flu.

Every cemetery was required to have an area set aside for the poor.

The public graves, the PG section.

And they were basically buried in order as they came.

But during the flu epidemic, they just dug a trench and then they filled them in.

That summer was pretty busy.

I guess.

(suspenseful music with indistinct chatter) - [Katie Thornton] This crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, has forced a lot of people to think differently and creatively about death and memory as well.

- [Angela Woosley] People who are seemingly healthy and seemingly capable, who felt that they had decades, decades left in their lives, were taken by COVID.

- It was horrible for people.

You couldn't even see their loved one before they passed.

It was absolutely horrible.

- We were hearing stories and meeting with people who hadn't been able to say goodbye in person to people they loved.

They weren't able to visit towards the end of the life.

And they might not have even been able to visit after that person had died.

- My own family is a part of that.

So I lost my grandfathers to COVID during this, and we have not had their services yet either.

So it's very, this whole time has been very personal for, sorry.

- It's very difficult times.

I have seen people come here and just sit down by a marker and just cry alone.

I can't say that I saw so much of that before the pandemic.

- What we're seeing now, as we come a little bit out of the pandemic, a bit, cross your fingers, is that people had to delay services and now they're interested and able in holding those services and they understand why it's important.

Being denied the opportunity or possibility to have a service, helped them realize how important it was to have something, To remember that person, commemorate their life, celebrate them.

And so we're seeing kind of an increase in memorial services after the fact.

Months or even a year after that death has occurred.

The heartbreak that funeral directors witnessed and were a part of, at the end of life in the midst of that pandemic was devastating.

It was devastating to our whole country and to funeral directors, in particular.

- [Kelly Leahy] We run in line with the, you know, the EMTs and the doctors and the nurses and all those people.

And so I do think people forget about funeral directors and about cemetery workers and all of this.

Like, I don't think that's as top of mind as those other professions, but the impact is really similar.

- COVID made death for some people so much more real.

- We've never really had to face something like that before.

Here it is.

It's right here.

This could impact any of us tomorrow.

And so now we're forced to have these conversations.

When we saw COVID starting.

When we saw the numbers, starting to rise, people started saying, I need to get my will in place.

I need to get my advanced care directive in place so that I have all of the things that I want laid out for people so there are no questions.

- Coronavirus--like countless health crises through human history--has changed the way we live, and the way we die.

Other forces of change are at work too.

Even in these seemingly timeless places, cemeteries and deathcare providers everywhere are innovating, looking to ancient and recent history around the world, and to technology, they're exploring new ideas, finding ways to adapt and thinking creatively to help families find meaning in a changing society.

(quiet piano music) - [Christin Ament] We're in this great questioning right now in our culture.

A huge cultural shift is happening where we're starting to question everything.

- [Julia Gillis] The end of life world is changing.

Traditions are changing.

Rituals are changing.

- [Paul Aarestad] The traditional church service or this or that is changing.

People aren't affiliated necessarily with synagogues or church or mosques like they used to be.

- [Kelly Leahy] Ceremony's really important for people, but with religion becoming less a part of people's lives, I think the desire for ceremony is still there.

And the question for our industry is how do we help them with that when they don't know what to do?

- New traditions and new rituals is what's gonna happen.

- [Kelly Leahy] Looking to Europe, Asian countries, all types of other cultures.

I think that we'll be able to pull from that.

What we can do with stories and video and links to things and websites and all of these things.

- [Julia Gillis] Things like virtual memorialization, we have the place, but then you also have the stories.

And how do you tell those stories?

And that's where some digital tools can really come in and help us.

- It's called "Find a Grave."

We have quite a few volunteers come in and it's a fun thing to do.

You're out there.

You're stomping through the grounds.

You're reading stones.

You're learning about history.

You're making new friends.

This is virtually stored online, and you can see these monuments, markers.

And then you had that ability to write a story.

(upbeat piano) - The customization and personalization that people want now, that's ever evolving and almost kind of a constant struggle to keep up with.

The Millennial generation, the next generation will want very different things than the Boomers, than we're seeing now.

I think we're going to see a lot more natural requests, involvement, desire for more green and natural things and elements.

If we do new buildings, do they have solar?

Are they respectful?

Are they made with more natural materials?

If we offer new burial sites, can we forego the use of concrete?

Can we offer, maybe offer things that are intended to biodegrade, right?

So I think all of those things will have a strong push from the Millennials.

And I think that we'll have to really think about those items and what that means.

'Cause cemeteries are meant to be permanent places, but they're asking for impermanence.

So it's going to be an interesting ride.

- [Angela Woosley] That movement towards natural burial, in a way is kind of coming full circle and bringing that way of interacting with the earth to a simpler approach.

So we see all, a variety of those things.

So for instance, the cremation itself, flame-based cremation has a lower carbon footprint than your average traditional burial.

But there's also alkaline hydrolysis cremation, that instead of utilizing flame, utilizes a strong alkaline solution and has a much lower carbon footprint than flame-based cremation.

Minnesota was actually the first state to legally recognize alkaline hydrolysis as a form of disposition.

And in addition, we're seeing that increase in natural burials and there's a wide range of what's considered natural.

Some people are opting for a bamboo casket or a seagrass casket because those fibers are much more renewable, quickly renewable, than the traditional hardwood or softwood caskets.

So it can look like all sorts of different things all the way up to a full conservation prairie, where people are buried and commemorated.

In a way, that kind of skips the middleman of cremating and then burying the cremated remains, to have a much, much lower, almost nil, carbon footprint or impact on the earth.

That's an amazing transition to be able to recognize and honor.

To say, I am feeding the trees, I am feeding the plants.

My life is transforming into energy for the planet.

(solemn music) - Jewish burials might be quite a bit different than those maybe of the Greek background and the Chinese background.

There are Ethiopians, Somalis, Indigenous people, Hmong people, another set of customs.

- Here in Minnesota, we have all of these amazing communities that make our state so rich.

Our funeral professionals need to be adaptive and responsive to the needs of those communities because our rituals and our ceremonies at the end of life are profound and important.

- What we're starting to see in the death and dying industry is a lot of emergence of how other cultures honor their dead.

How other cultures honor the dying process.

Bringing in Buddhist aspects and bringing in African traditions and bringing in Islamic traditions and bringing all these into some sort of a melting pot of honoring and walking this line of appreciating different cultures and honoring them, but not appropriating and taking away from and claiming.

So we're seeing kind of hybrid version of grief-focused tea ceremonies that are rooted in Buddhist lineage, but it's been stripped of that and offered to anybody who seems to be grieving.

So there is a perfect example of kind of blending these traditions and offering people healing spaces.

And re-imagining the way we die and grieve and honor.

- [Paul Aarestad] What's changing is not only the cemeteries, but it's the whole death industry.

- [Kelly Leahy] Funeral homes, crematories, cemeteries are a lot like every other industry in which there used to be many Mom and Pops.

And then they've slowly become consolidated.

There are national chains now.

The bronze manufacturers, there used to be many, many, many, they've all primarily been bought up by one large firm.

Same thing with vendors for gravestones and headstones and monuments.

There used to be many in the Twin Cities.

In fact, there was one across the street, but no longer.

- I would say in the last five to ten years, the conversations around end of life have really changed.

- [Julia Gillis] There's a movement to change how we think about end of life.

- So you'll hear stories about the death positive movement, where maybe we shouldn't do like we've done in points in the past and kind of shoved death aside and keep everything real dark and not talk about it.

But let's maybe be a little bit more open about that.

- It's okay to think about the fact that you and all of us are going to die.

- I think with the advent of modern medicine, we are seeing people have that option of staying alive a lot longer than maybe we would have anticipated or that maybe people care to live.

Before modern medicine, it wasn't an option for us, so why would we sit and deliberate over these kinds of conversations?

We'll just die when time is here, but now we do have all of those innovations and so it raises a lot more question marks and a lot more conversations need to be had.

Having these discussions around end of life, we're starting to see people be more okay with deciding what feels comfortable for them.

- [Angela Woosley] End of life doulas or death doulas, they're sometimes called, who are lay people who help the dying reconcile with their upcoming death and also help families connect and be present in those moments.

And in a way they can kind of transfer that role and that care across that threshold to smooth and ease the transition into funeral care.

- The other thing in the industry is how many women are in this now.

So I graduated in 2003 and we were the first class from the University of Minnesota that was a majority women, I think only by one, but that is now I think, every class or almost every class since mine is very close to that.

So the amount of women in the field, that's changing things a lot too.

- Being able to partner and carry and support people across that threshold and help them realize and understand the reality of that death and provide space for people to come together and mourn publicly and lean on one another is a noble profession.

And I feel like cemeteries, funeral directors and morticians in Minnesota, understand that role and are really proud of it.

(upbeat calm music) - [Chris Makowske] I think the future of cemeteries, not only to bring people in, but to connect people with the community, it's to start looking at what's meaningful to people today.

- I'm excited.

I know we're on the cusp of some really great things, but it is a constant discussion of how to keep the traditions and all the things people love, but find the things that the next generation is going to love and appreciate as well.

- We've decided to do something radically different.

We've been told that we can give up our bodies to the Medical School at the University of Minnesota, and then they will do the cremations and then give the cremains to our children.

Make it easier for them.

- Planning ahead for your own death is a gift to your children, your next of kin, your extended family, because we want to do what the dead wanted.

- And when the time comes, when you do die, that they could concentrate on the stories and the memories and not have to deal with the details and trying to figure out what you wanted or didn't want.

- My wife and I have just been talking about this, you know, it's like, well, what do we want to do, you know?

It's kind of like what my daughter wants, you know?

'Cause, you know, you don't know where your kids are gonna end up and how often they're going to come back and visit.

- Our bones obviously should be returned to the earth here and become a part of the earth here.

And the earth here is related to everything else.

The earth, the trees, the sky are all connected.

It's all one burial ground.

I look forward to joining back with my ancestors and continuing our story.

We believe we came from the stars and will return to the stars.

(upbeat music) - [Chris Makowske] What is a cemetery about?

Well, it's a place for the community to come back together and to remember.

And to really kind of look at those questions that have a lot of meaning in our life.

- [Peggie Carlson] I still think there are an awful lot of people that are afraid to go into cemeteries.

- [Michael Wong] You know, I don't know how many people these days come to visit people that have passed, in the cemeteries.

- [Kelly Leahy] It's a place to remember.

It's also lessons in history, a place for people to think about their genealogy, where they came from.

- [Katie Thornton] This repository of stories and also of plant life and animal life.

- [Peggie Carlson] People drive by, and they, no idea what they're missing.

- [Katie Thornton] I have personally found cemeteries to be very comforting because it's sort of the only space where death and loss and that reality is sort of given real estate in an urban environment, which is, really valuable and really special.

And you kind of come to a cemetery and feel less alone, know that there are people who have loved every single person who is remembered here and that every single person lived a life, has a story.

And you remember that you're not alone in grief.

- [Angela Woosley] Knowing that I'm going to die, helps me live my life more fully.

It can encourage you and inspire you to live your best life now because tomorrow is not promised.

- [Chris Makowske] Even this location is a reminder that there were people here before us, that we're not just all about ourselves.

That there's a whole history that we're built on.

There's so many stories that were built into the lives that we have today and that we're part of that chain.

- [Angela Woosley] It's a monument of yesterday for future generations.

Cemeteries are a reminder to the living that we will not be forgotten and that we can connect with our ancestors and our relatives beyond that veil of death.

(slow, thoughtful music) - "Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story" is a TPT co-production with Lakewood Cemetery.

(upbeat tones)

Deathcare During Global Pandemics

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 3m 55s | Infectious diseases take lives, but they also complicate the living's ability to grieve. (3m 55s)

A Movement to Make Cemeteries Beautiful

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 2m 48s | Grisly graveyards in Europe led to a new approach to cemetery design. (2m 48s)

Notable Burials at Lakewood Cemetery

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 5m 49s | Some very interesting people are interred at Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis. (5m 49s)

Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story | Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Special | 30s | Cemeteries reflect their community's origins, history, people, and future. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Remembering Place: A Cemetery Story is a local public television program presented by TPT