VPM News Focal Point

Reparations and Restitution | December 15, 2022

Season 1 Episode 20 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Relating to Monticello; Science of generational trauma; uncovering Roanoke’s Black history

Descendants of enslaved people learn the truth about their ancestors’ history at Monticello; examine the science of generational trauma stemming from experiences like slavery and the Holocaust; “Hidden in Plain Site” spotlights Roanoke’s Black history.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

VPM News Focal Point

Reparations and Restitution | December 15, 2022

Season 1 Episode 20 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Descendants of enslaved people learn the truth about their ancestors’ history at Monticello; examine the science of generational trauma stemming from experiences like slavery and the Holocaust; “Hidden in Plain Site” spotlights Roanoke’s Black history.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANGIE MILES: America is a forward looking nation, known for creativity, innovation, and progress.

But are there times when progress requires stopping to look back?

In this episode, we'll talk about examining certain elements of our past.

We'll hear that reflecting on some of the most traumatic parts of our shared history is the best way to move forward towards healing.

This is VPM News Focal Point.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by Dominion Energy, dedicated to reliably delivering clean and renewable energy throughout Virginia.

Dominion Energy, Actions Speak Louder.

The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪ ANGIE MILES: Welcome to VPM News Focal Point, I'm Angie Miles.

In this episode, we are talking about history and race.

And if anyone thinks there's nothing more to say or to see on that subject, we have a few stories that may change your mind.

We're offering a more complete picture of Thomas Jefferson's legacy, a science-informed look at the cost of racial trauma, and a virtual way to bring history to life.

But first, the Virginia Department of Education is rewriting the standards that guide the history curriculum for kindergarten through high school.

Multimedia journalist, Adrienne McGibbon, spoke with educators concerned about which lessons could be left out.

ADRIENNE MCGIBBON: The Virginia Department of Education is considering two very different versions of state history standards.

The first, compiled by educators, academics, and the public, over the last two years.

The second, created during the Youngkin administration, has been criticized for diminishing minority achievements and ignoring the lasting impacts of slavery.

Two heavyweights in Virginia higher education are critical of the new draft.

ED AYERS: Because history is a collaborative exercise, in which we all build upon the generation that came before us.

We've seen that history is not just a luxury, but it's the very fabric of what the Commonwealth is, our self-understanding.

CASSANDRA NEWBY-ALEXANDER: Your children are walking into a global society, and when you don't understand who other people are, and what, and how they're interacting, and what has impacted them, what has perhaps traumatized them, then there is no way that you can live peacefully and peaceably with other people.

ADRIENNE MCGIBBON: Both educators worked on the first draft update.

Governor Youngkin, who made education a central part of his campaign, admitted to mistakes and omissions, saying he wants to teach all of our history, the good and the bad.

ANGIE MILES: The State Department of Education is currently integrating both drafts and will address concerns raised about omissions and factual errors.

ANGIE MILES: New polling from PEW Research finds that Black and white Americans are far apart on the question of reparations, that is, whether compensation should be offered to descendants of enslaved Americans.

77% of Black respondents say yes, only 18% of whites support reparations.

We put the same question before people of Virginia.

STEPHANIE JOHNSON-THOMPSON: Where are we drawing the line?

Do we feel $10,000 is enough?

Do we feel a million dollars is enough?

For each person it's gonna be very different.

Some people may not think of slavery as a big topic issue, and would say yes, they should settle for a very limited amount.

And others should say no, there is no way that you can financially reimburse or compensate descendants of slaves, because that's not gonna be enough.

DIANE HARPER: I think it depends on the situation.

If it was stolen land, inheritance that was taken away, I do think that that compensation would be necessary.

JIM BERNHARDT: The answer is yes I do think that.

The next question, how to do that, I don't have an answer to that one, 'cause that's a real complicated question.

ANGIE MILES: Interestingly, all the Virginians we asked said the more difficult question is, how to pay reparations?

Revered Founding Father Thomas Jefferson enslaved more than 600 people at his mountaintop home, Monticello.

Our special correspondent in Charlottesville, Dennis Ting, shows us how the Thomas Jefferson Foundation is unearthing long buried secrets and recognizing relationships beyond the color line.

DENNIS TING: Every year, hundreds of thousands of people come to Monticello here in Charlottesville to learn about American history, and for some, to connect with their family history.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: I am Gayle Jessup White.

I'm public relations and community engagement officer here at Monticello.

DENNIS TING: Gayle Jessup White is no stranger to the history of Monticello.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: Little children 8, 9, 10 years old, made the bricks that built Monticello.

Go ahead and put your finger in.

DENNIS TING: But the home of the third president of the United States of America isn't just her office.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: I'm descended from Thomas Jefferson.

DENNIS TING: Jessup White isn't just any employee at Monticello.

She first heard she was related to Thomas Jefferson when she was just 13 years old.

A huge surprise then, especially because Jefferson was her favorite president at the time.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: I couldn't put together in my 13-year-old mind how a little Black kid growing up in Washington DC could be related to the third president of the United States of America.

DENNIS TING: This set off a decades-long search for the truth of her history.

But while she thought she was a descendant of Jefferson and Sally Hemings, a woman he had enslaved and had children with, she learned later she was actually descended from Jefferson and his wife Martha, through one of their great-grandsons.

And- GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: I'm also descended, I learned, from a brother of Sally Hemings whose name was Peter Hemings.

DENNIS TING: Peter Hemings was enslaved at Monticello, working as a cook, a tailor, and a master brewer, working in the rooms she now walks through generations later.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: So this space for me is hallowed ground because I know my great-great-great-grandfather was here.

DENNIS TING: Like many other descendants of those enslaved at Monticello, Jessup White first learned of her family line through oral history, passed down from generation to generation.

Many of these stories do not focus on their ancestors' enslavement, though it certainly casts a large shadow.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: I feel their sacrifice.

I feel their suffering, but I also feel their joy.

ANDREW DAVENPORT: They chose instead to talk about their family members, people that they know, places that they know.

DENNIS TING: For decades now, historians like Andrew Davenport have worked to preserve these oral histories from those enslaved at Monticello, to paint a more complete picture of the experiences of those enslaved and of the slave owner, Thomas Jefferson.

ANDREW DAVENPORT: Each of them speak to personal flaws of Jefferson.

Each of them speak to personal qualities of great brilliance in Jefferson.

DENNIS TING: Davenport, the director of the Getting Word Oral History Project, says the more than 200 oral history interviews collected from people enslaved by Jefferson show a complex figure.

The writer of the Declaration of Independence, declaring all men to be created equal, yet a slave owner who owned more than 600 people during his lifetime.

ANDREW DAVENPORT: We can look a historical figure in the eye and understand that they are flawed and brilliant at the same time, and doing both, I think, will be our gift to the American public moving forward.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: And that's hard to deal with.

That's hard to face, especially since I admired him so, and especially since his blood runs through my veins.

DENNIS TING: But Jessup White says learning about Jefferson's complicated history and the stories of those he enslaved has helped her come to terms with who they were, not as mythological figures, but as human beings.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: My ancestors literally built Monticello.

Those people, my ancestors, made Monticello work and they represent the millions of people enslaved in the United States of America.

DENNIS TING: For Jessup White, her search for the truth has led her to not only find her ancestors, but also current relatives, some working just down the street, like Andrew.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: He's my cousin.

ANDREW DAVENPORT: My great-great-grandfather and her great-grandmother are siblings.

DENNIS TING: It's been a journey spanning decades, but Jessup White hopes sharing her family's story will help future generations better understand Thomas Jefferson and the history of this country, and continue the work of honoring the enslaved people and their role in shaping America.

GAYLE JESSUP WHITE: Discovering this history has made me whole.

It's given me a family.

It's given me roots, and it's given me joy.

DENNIS TING: That work is still continuing.

Just earlier this year, Monticello held a rededication ceremony for the burial ground for enslaved people.

This came after a four-year project that was guided by the descendants of the people enslaved at Monticello.

in Charlottesville, I'm Dennis Ting for VPM News Focal Point.

ANGIE MILES: Gayle Jessup White tells the full story of her family history in her recent memoir, "Reclamation: Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and a Descendant's Search for her family's Lasting Legacy."

VPM News Focal Point is interested in the points of view of Virginians.

To hear more from your Virginia neighbors, and to share your own thoughts and story ideas, find us online at vpm.org/focalpoint.

ANGIE MILES: "From the ships," that is a phrase sometimes used by African Americans.

It refers to people stolen from their native Africa and enslaved in America.

Only the strongest survived the brutal voyage across the Middle Passage.

"From the ships" means that if you are a descendant of an enslaved American, you have inherited extreme resilience and strength.

Modern science is revealing that through learned behavior and even altered genetics, descendants of traumatized individuals can actually carry inherited trauma in some form, for generations.

So the pain of war, starvation, the Holocaust, and slavery can echo through families and communities for years after the fact.

An advisory, this content will be difficult for some.

FOUNTAIN HUGHES: My name is Fountain Hughes.

I was born in Charlottesville, Virginia.

My grandfather belonged to Thomas Jefferson.

My grandfather was 115 years old when he died and now I am 101 year old.

ANGIE MILES: This is one of the few surviving audio recordings of a formerly enslaved American.

FOUNTAIN HUGHES: If I thought that I'd ever be a slave again, I'd take a gun and end it all right away, because you're nothing but a dog.

You're not a thing but a dog.

ANGIE MILES: The interviewer called him Uncle Fountain.

Shallie Marshall called him Pap.

He was her great-grandfather and for much of her early life they lived under the same roof.

SHALLIE MARSHALL: It must have been a tough time for him when he was a kid because he was young when the Civil War ended.

ANGIE MILES: He'd left Charlottesville in 1881, eventually settling in Baltimore, and speaking about the bitter fruit of slavery, almost never.

SHALLIE MARSHALL: People had to go and fend for themselves and he said he had to eat rats in order to survive.

He did tell me that.

ANGIE MILES: For many Americans, the idea of slavery seems ancient something in old books and so far in the distant past that it has no bearing on our lives today.

PEIGHTON YOUNG: I think what is important to understand is that it was something that didn't happen, you know, so long ago, that it's completely removed from public memory in the sense that we still carry the legacies of it.

Physically, I think emotionally, spiritually, culturally, communally, it's still there.

It's still a part of who we are.

ANGIE MILES: Peighton Young is a scholar and historian who has volunteered at Woodland Cemetery, one of many predominantly Black historic cemeteries in Virginia.

Places that fell into severe disrepair because of lack of resources and regard but are being reclaimed and repaired by volunteers.

Much of Young's work is in honor of ancestors.

John Jefferson is buried somewhere at Woodland.

Young has been searching for the exact location for years.

PEIGHTON YOUNG: Not everybody is so privileged to have a stone that they can come to.

All I wanted was to just go to the store, get some flowers, come to his grave and say, “hey, we remember you, ” and I can't do that.

And even though I'm, you know, 80 plus years removed that it's a kind of pain that I can't even really describe because it's something you should have.

BARRINGTON ROSS: My Mother, Silva, and her mother was bought from the Rutledge family in Charleston... ANGIE MILES: Given the scarcity of documentation about the individual lives of enslaved Americans, only a few descendants are fortunate enough to have a record of what their forebearers endured.

Barrington Ross's understanding of slavery is enhanced by the written narrative of his great-grandfather, Jim Henry, Jr. BARRINGTON ROSS: When slavery was over, everyone was happy but it still was a scar in the memory of Jim Henry.

Jim Henry did not forget.

How can you just walk away from someone owning you?

How can a individual pick up another life, immediately following the gruesome toil of slavery on their lives and after a war and just think that everything is just going to be okay?

ANGIE MILES: Trauma expert, Simone Jacobs, says everything was and is far from okay in the aftermath of slavery.

SIMONE JACOBS: Slavery was a systematic process of abuse that went on for hundreds of years.

We have to understand that in order to keep a group of people subjugated you have to destroy family connections.

You have to destroy attachments.

And so what slavery did, how you kept 30 people who were working in your fields from attacking the 10 people up in the big house, was that you made sure that they were constantly living in fear.

I think the statistics are like one in three marriages were broken up, one in five children were taken away from their parents, but that's just the statistics.

We know that it was much worse than that.

And we also know that you only have to do that to one family for it to have a devastating effect on everybody else.

ANGIE MILES: Jacobs says that by disrupting attachments among family members enslavers caused deep destabilization that can continue for generations.

Kerri Moseley-Hobbs with her family's More Than a Fraction foundation is exploring the impact of their family's enslavement at Smithfield Plantation in Blacksburg.

KERRI MOSELEY-HOBBS: And that's the reason why we keep talking about race because it's still a pivotal part of this society, right?

Because we're still in the transition out of slavery.

So race is still a huge part of it.

We're still dismantling a lot of the laws that come from that period.

We're still dismantling some of the prejudice and it's really not that far in the past.

So if the American story, including slavery, was a 20-chapter book, we're only on chapter two.

And we got to chapter two and we found out the chapter one was written wrong and now we have to go back and clean it up.

I'm so sorry you guys, we're not that (laughs) far ahead as we think.

ANGIE MILES: Another reminder of the relative proximity of slavery and all its costs starts here.

This is Massie's Mill, Virginia.

the Nelson County town where Abram Smith was born and lived until a few years after the Civil War.

Smith's youngest son Daniel, passed away in October, but before his death, he wrote about his life in Son of a Slave.

He recalls harrowing stories his father would share, including about the capture of two runaway slaves.

DANIEL SMITH: They found them up a tree, so they hanged them in that tree and my father had sort of tears in his eyes like it could have been his brother, or, I mean-- ANGIE MILES: Brainwashed is the word Smith used to describe the lingering effect of slavery on Americans.

He related a story of his mother chastising his older brother for having bought her a house.

DANIEL SMITH: She came downstairs and said "Now you know the house is too good for me.

"It's better than the houses I clean."

Now, that's brainwashed.

My mother saying that.

A whole nation has been brainwashed.

ANGIE MILES: Simone Jacobs says, it can be difficult for people who are not Black to understand that each time a racially-motivated incident occurs, whether it's a microaggression in an individual's life or a widely publicized attack on someone, it has the potential to re-traumatize.

Jacobs says that makes it difficult for Black people to develop an internal sense of safety.

SIMONE JACOBS: And from a therapeutic perspective, when I'm working with a client who's been sexually abused or physically abused, most of the time the abuse is in the in the past.

All my goal as a therapist is to make sure that they get out of the abusive situation.

When we're talking about racial trauma there is no getting out.

The trauma is ongoing, so it is a different kind of trauma.

♪ ANGIE MILES: The sense of safety aided by connection and belonging is what begins to occur when people acknowledge the pain of the past and actively look for ways to heal.

More universities and historic places are becoming more honest about the slavery that built and sustained their institutions.

At Patrick Henry's last plantation, Red Hill in Campbell County, an annual event brings descendants of those who lived, worked, and died there.

Barrington Ross's great-great-grandfather, Jim Henry, Sr., was once property of Patrick Henry's family.

Ross is among those who've traveled far to learn about their people and to show respect.

BARRINGTON ROSS: Enslaved people's descendants are still around and then there's still open wounds that need to be healed.

ANGIE MILES: Peighton Young is Red Hill's historical advisor and sees this as the kind of project that will begin to heal trauma through openness and honesty.

PEIGHTON YOUNG: I think it's important to talk about our history or the legacy of slavery because we don't want to silence lives that actually meant something, that contributed to the lives that we're living now, that contributed to our communities, our families, our legacies.

They deserve to be talked about just as much as Patrick Henry or any other Founding Father does.

ANGIE MILES: Simone Jacobs says that anxiety, depression, aggression, or low self-esteem can be caused or complicated by generational trauma.

And she says, Even among successful descendants who seem unaffected, the drive to overachieve can be an outgrowth of the trauma experienced by ancestors.

One of the simplest illustrations of the legacy of slavery is the wealth gap.

The Federal Reserve reports that Black and Latino families earn on average about half of what the average white family earns, and the gap is widening as the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

But some people are choosing individual reparations as a way to help.

In Focus this week are Duron Chavis and Callie Walker of the Central Virginia Agrarian Commons, an exceptional gift is intended to help heal some of the inequities of the past and to make a better way forward for some Black Americans.

ANGIE MILES: Talk about what prompted you to work with the Agrarian Commons to make your land available for Black farmers.

CALLIE WALKER: This is an injustice of the duration in time and intensity that it's the kind that cries out to God for relief.

I take the biblical perspective that God hears the cries of the oppressed.

DURON CHAVIS: The 75 acres or so that Callie Walker's donated will be part of a system of rural and urban land that is being redistributed to Black and Brown farmers.

Our initial plan is the development of some form of income generation for folks that aspire to farm on the Amelia property.

ANGIE MILES: Black land ownership was a major accomplishment in Reconstruction and immediately after and then almost systematically, or seemingly systematically, a lot of that land was lost, was taken away from people.

Would you speak a little bit about some of the ways Black people have lost land?

DURON CHAVIS: So when we think about access to loans for your farm, rents and other programs to help mechanize and improve your farming systems, in rural communities, African Americans were denied those access to those programs.

ANGIE MILES: You personally didn't enslave anyone.

Why did you feel compelled to give, to try to right some of what was wrong?

CALLIE WALKER: To me, when I hear the word "reparations," I do hear the word "repair."

By the time I made this land donation, I thought, "Hey, here are my husband and I with no kids.

There's no one we have to leave this to."

We said, "We're in a perfect position to donate this land to Black people."

You can watch the full interview on our website ANGIE MILES: Now you can travel through time to uncover hidden history around you.

Hidden in Plain Site is a virtual reality immersive experience designed to change cultural education for any underrepresented group.

The project saw success in Richmond and is now uncovering the Black experience in Roanoke.

DONTRESE BROWN: We want to talk about that ugly history.

One of the main focuses of the partnership between myself and Dean Browell and David Waltenbaugh as we formed "Hidden in Plain Site" was to really help change the narrative to the true stories and adding an element of immersiveness, almost like putting someone in someone else's shoes.

Come with me.

I want to show you something.

"Hidden in Plain Site" exists to use technology to change the future of culture education for any historically underrepresented group.

We provide the platform for their voices to be heard.

What we do is we collect archival images and then we use virtual reality film and video and technology to orient an individual where they are and then transitioning that point of where they are to a historical point in history.

We feel that there is an opportunity that everyone walks by different sites in their cities, not knowing the historical context from any historically underrepresented group simply because it's been "Hidden in Plain Site".

Right now, we're working with the Black American narrative.

The places that you can see in "Hidden in Plain Site: Roanoke", we're going to do six sites.

We're going to talk about Henrietta Lacks.

We're going to talk about the Borough Memorial Hospital which was the first Black hospital for Black Americans in Roanoke.

We're going to talk about the Old Lick Cemetery, which was destroyed to have an interstate run through.

(cars rushing) And we're going to talk about the Civic Center, which destroyed a Gainsboro neighborhood, which was a Black neighborhood that they completely destroyed to build this Civic Center.

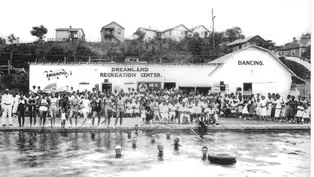

We're going to talk about a recreation center there called Dreamland.

The only place that Black Americans could go to swim and play ping-pong and hang out.

Once individuals start to understand the true history behind either their culture or some other historically underrepresented culture, then we understand that there is an opportunity for us to use that history to lift those voices, but then as a society, as a community, as a country, to come together and start to move forward into creating a more equitable place for everyone.

ANGIE MILES: How can historical harm within our communities be repaired beyond material recompense?

Today's stories may help us reflect on that question and together perhaps, answer it.

Watch our full interview on Virginia's Black land loss and gain on our website vpm.org/focalpoint, and view an extended version of our generational trauma story there too.

Also, find resources for healing.

Thanks for spending time with us, we'll see you soon.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by Dominion Energy, dedicated to reliably delivering clean and renewable energy throughout Virginia.

Dominion Energy, Actions Speak Louder.

The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪

Young author Joshua Clemons is speaking up

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep20 | 1m 8s | He’s asking others to remember the importance of those who were enslaved in America (1m 8s)

A battle in Virginia’s classrooms about our past

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep20 | 1m 17s | State educators say Governor Youngkin is turning history lessons into a political battle (1m 17s)

The impacts of slavery are still felt

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep20 | 12m 29s | More than one hundred fifty years after emancipation, slavery continues to take a toll (12m 29s)

Descendants’ Voices at Monticello: Gayle Jessup White

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep20 | 4m 47s | Gayle Jessup White is related to the enslaver, Thomas Jefferson, and the people he enslave (4m 47s)

In Focus | Callie Walker & Duron Chavis

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep20 | 19m 19s | During the 20th century, Black Americans lost 90 percent of their land across the U.S. (19m 19s)

Reparations and Restitution | People of Virginia

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep20 | 55s | We asked if compensation should be offered to descendants of enslaved Americans. (55s)

Uncovering stories that are “Hidden in Plain Sight”

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep20 | 2m 36s | Uncover stories that are “Hidden in Plain Sight” with this virtual reality experience (2m 36s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM