VPM News Focal Point

Restorative Justice | April 18, 2024

Season 3 Episode 8 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

There is a movement in Virginia to evolve our judicial system.

There is a movement in Virginia to evolve our judicial system to decrease the emphasis on punishment and focus more on healing or restoring what was damaged by criminal or civil offenses. We explore restorative justice and see who benefits.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

VPM News Focal Point

Restorative Justice | April 18, 2024

Season 3 Episode 8 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

There is a movement in Virginia to evolve our judicial system to decrease the emphasis on punishment and focus more on healing or restoring what was damaged by criminal or civil offenses. We explore restorative justice and see who benefits.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANGIE MILES: America's approach to criminal justice has undergone somewhat of a sea change in recent decades.

While we still hear politicians talking about being tough on crime, there is also a movement to do more than punish to work towards repairing the damage of wrongdoing.

Restorative justice aims to address both the victim and the perpetrator of crime.

Now, Focal Point examines the roots, the reach, and the repeat offense rates associated with this more compassionate approach to criminal accountability.

VPM News Focal Point is next.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪ ANGIE MILES: This is VPM News Focal Point, I'm Angie Miles.

Restorative justice can be defined many ways, but the essence of this increasingly popular approach to fighting crime is the effort to heal the harm caused by crime, to consider the individuals involved and the wellbeing of the entire community.

Also to provide an intentional response that goes beyond locking people away.

Incarceration costs Virginians approximately $40,000 per inmate per year.

The financial burden escalates when someone becomes a repeat offender or recidivates.

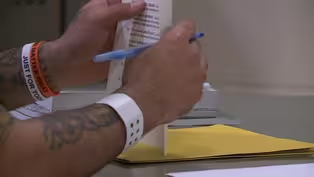

Lowering recidivism is one of the aims of a restorative justice recovery program housed at Chesterfield County Jail.

Special correspondent A.J.

Nwoko takes us inside.

DeWARREN FITZGERALD: I've done probably 17 years since I was 18, in and out, in and out.

A.J.

NWOKO: In just over three months- DeWARREN FITZGERALD: 97 days.

A.J.

NWOKO: DeWarren Fitzgerald will be a free man and this time he intends to stay that way.

DeWARREN FITZGERALD: Ive always thought that coming to jail, getting out and coming back was the normal thing to do until I came into this program.

A.J.

NWOKO: That program is called Helping Addicts Recover Progressively or HARP.

It's been a staple in the Chesterfield County Jail for nearly a decade, investing in inmates like Fitzgerald with the hope that this is the final sentence they'll ever serve.

DeWARREN FITZGERALD: Until I got arrested in Chesterfield, I thought that was my life.

A.J.

NWOKO: In addition to mental health services and substance abuse rehabilitation, HARP participants are taught new skills to prepare them for the workforce.

DeWARREN FITZGERALD: I got my forklift license here.

I got PRS certified.

A.J.

NWOKO: All of this to curb the county's recidivism rate.

BAILEY HILLIARD: Restorative justice really makes a lot of sense.

A.J.

NWOKO: Bailey Hilliard is the rehabilitations program manager of the jail.

She says the county's methods are the key to keeping the recently-released from returning to damaging habits.

(door clicking) BAILEY HILLIARD: For us to be a part of a restorative justice system, it means that we are doing something very different from a lot of people.

A.J.

NWOKO: According to a 2019 review of HARP by VCU Health, from 2016 to 2019, 45% of inmates who didn't participate in HARP were rearrested after being released, compared to just over 28% of graduates.

However, the review did not detail how soon after release former inmates reoffended.

Virginia had a 20.6 recidivism rate for state set report re-incarceration rates within three years according to the U.S. Department of Corrections.

But Hilliard says recidivism rate alone does not completely illustrate Virginia's success.

BAILEY HILLIARD: If you're coming back to jail twice a year instead of six times a year.

That, to me, is a reduction, for reducing behaviors.

A.J.

NWOKO: But Fitzgerald believes he's made that turn and he's ready to prove it.

DeWARREN FITZGERALD: My story is just beginning.

A.J.

NWOKO: For VPM News, I'm A.J.

Nwoko.

ANGIE MILES: Virginia as a whole has consistently boasted a lower recidivism rate than most other states, although critics say that it's difficult to compare when the measurement criteria varies so widely from state to state.

ANGIE MILES: The latest data from Virginia State Police shows our state has experienced an increase in violent crime in the past two years.

Focal Point asks opinions of people of Virginia when it comes to ways to discourage crime or to prevent repeat offenses, what can make a real difference?

MARCUS MINNICK: To discourage anyone from being criminal is have them talk to people who have served time, like help them realize like, ‘hey, I served time.

This is my experience in there and it's not something you want to go through.

GABE KALINA: Let's help them get back on their feet because they've been out for so long, out of the real world.

And like, we can help them with getting on their feet, getting jobs, help them find houses.

BRENDA DAVID: Making people be responsible for their actions.

and I'll just give an example of if if you vandalize a place, make you be responsible for cleaning that place up.

ROBERT HALMAN: Give them something to do, create something.

I mean, it's always some kind of program out there that you could create and somebody will listen to you.

That dont mean they're going to listen all the time.

But somebody will listen.

And it gives people hope.

And they think, well, “If I can do this today, what can I do tomorrow.

” ANGIE MILES: With a focus on the future, school districts throughout the nation and right here in the Commonwealth, are redesigning old school discipline measures and shifting towards a more holistic approach, consistent with restorative justice.

Multimedia Reporter Keyris Manzanares explores how Lynchburg City schools are adopting new practices to build a positive school culture, where students learn from their mistakes.

(traffic humming) KEYRIS MANZANARES: For the past year, Lynchburg City Schools have taken a new approach when it comes to suspending students.

Instead of serving suspensions at home, Lynchburg City middle and high school students now come to the Restorative Suspension Center at the Amelia Pride House.

ROBERE SANDIFER: I greet 'em every morning I dap 'em up.

'How are you?'

If they're frowning, 'Nope, we're not going in there.

Let's go talk.

What's going on?'

You know what I mean?

Whatever made you mad outside of here, don't bring it in here because I didn't do it to you.

You just have a good day, so.

And it seems that it's contagious.

Guardian is up.

You guys should be all working.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Robere Sandifer gets students ready for the day by playing relaxing music and enforcing a cell phone-free policy.

At the Restorative Suspension Center, students are engaged in all-day programming that helps them complete their classwork so they don't fall behind.

They also focus on resolving conflict, repairing harm, and healing relationships.

ROBERE SANDIFER: You know, I always tell 'em that you can use your past, you know, we all have adverse, you know, things in our past.

You can use it.

You can either use it as an anchor to weigh you down for the rest of your life, or you can use it as stepping stones.

Hindsight, how you think you probably should have handled that role?

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Sandifer says what helps him connect with students is that he's a Lynchburg native who's been in their shoes.

ROBERE SANDIFER: At the end, I think it's just repairing relationships that we have, that they have tarnished with the teachers, with each other.

You know what I mean?

I'm helping them restore all that, everything, restore themselves, you know what I mean?

'Cause a lot of 'em come from backgrounds where they don't have anybody at home helping 'em out, you know, to remind them what they can be.

You know what I mean?

So they're only hearing it here sometimes.

JERETT MARTIN: Whose done a Restorative Circle before?

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Jerett Martin, the center's coordinator, leads a circle that focuses on healing and understanding.

JERETT MARTIN: We're setting some boundaries and guidelines within the circle that transitions to the classroom and transitions to home/life balance, different things like that, that helps the kids.

And then one of the questions that I asked the kids today was, 'What's one of your biggest fears?'

KEYRIS MANZANARES: He also works with students on a game plan that will help them as they transition back to their base school.

JERETT MARTIN: Some students just want you to do small check-ins with them, and bring them treats or rewards because they've been doing so well.

So sometimes we do 21-day challenges where we reward the students for being consecutive for 21 days, and working off some habits that they may need to break.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Dr. Derrick Brown, the Director of Student Services at LCS, says the Restorative Suspension Center is already making a difference.

DERRICK BROWN: 80% of the time, when a student comes over here, they don't return.

So that's much better than the 60% that we were seeing, that they were continuing to get re-suspended.

And additionally, it was really encouraging to see that students aren't coming back for the same offenses.

And so only 10% of the time, students are returning for the same offense.

Whereas, before they were being suspended over and over for the same behaviors and the same referrals.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: Dr. Brown says this program holds students accountable, while also sending them a very important message.

DERRICK BROWN: We don't just throw them away.

It's important for them to be restored and for them to have people that care about them.

They need to know that when they make a mistake or they mess up, that doesn't mean that they're a bad student.

It just means that they made a mistake.

And we're all humans.

We make mistakes.

But we should always grow from those mistakes and we should learn and we should get better, and we shouldn't repeat those mistakes over and over and over.

KEYRIS MANZANARES: For VPM News, I'm Keyris Manzanares.

ANGIE MILES: The Restorative Suspension Center is just one part of Lynchburg's work to reform its school disciplinary measures.

The division says it hopes to expand the LCS Restore programming.

Aside from the center, Lynchburg also has restorative academies focused on holistic growth, both emotional and academic, for elementary and secondary students.

ANGIE MILES: VPM News Focal Point is interested in the points of view of Virginians.

To hear more from your Virginia neighbors, and to share your own thoughts and story ideas, find us online at vpm.org/focalpoint.

ANGIE MILES: The concept of restorative justice is decades old, but it is a broad philosophy that's creating new options for Virginians in a wide swath of institutions, jails, courts, and schools.

But what does restorative justice really mean and how is it being used in different ways?

Multimedia Reporter Billy Shields shows us how diverse this approach can be.

(wind whooshing) BILLY SHIELDS: Welcome to the south side city of Danville, where refurbished tobacco warehouses bear witness to the problems of the street.

Project Imagine is an entire department here tasked with aiding those under 21 using an approach called restorative justice.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: Project Imagine, we work with high risk and gang related youth, and the the object of Project Imagine, hence the name, means that the city had a motto of "Reimagine That", how the city could look.

And so, my question was, ‘how do you reimagine something that you never had an image of?

And the population that we worked with didn't really have an image of what success looked like as far as mainstream, what we may call success.

So we named it after that because it is our project to give them an image of a greater life.

BILLY SHIELDS: Robert David says it's an approach aimed at disrupting what advocates call the school to prison pipeline, where long school suspensions or expulsions end up increasing the likelihood that youth will land in prison.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: An example, there was a young lady, a couple of years ago, who was suspended from school and one of the school officials said that she had no redeemable qualities.

She was expelled.

Project Imagine came into play, we assisted her in getting her to a GED program, which she completed within two months.

BILLY SHIELDS: But what is restorative justice exactly?

How did it develop?

What does it aim to do?

CHLO'E EDWARDS: When people talk about restorative justice, generally, we're talking about the idea of strengthening relationships, working on collaborative problem solving, and when it comes to harm, giving a voice to the person harmed, but also the person that's causing the harm.

And when everyone's invested in this process, we get results, whether that's decreased suspensions in schools or lessening of crime in the criminal justice field.

SYLVIA CLUTE: Restorative justice began in the United States in the 1970s by Mennonites who were volunteering in a juvenile court.

Restorative justice is a conflict resolution process that seeks to address conflict and hold the offender accountable in a more reasonable way than is done in the court system.

BILLY SHIELDS: Richmond attorney Sylvia Clute introduced a type of restorative justice program called Unitive Justice to Richmond's Armstrong High School in 2011.

She wrote a book on the topic.

SYLVIA CLUTE: U.S. public policy towards our youth took a drastic turn in a very retributive direction.

We adopted zero tolerance school discipline.

(brakes squeaking) BILLY SHIELDS: When the program started at Armstrong, it had 583 disciplinary incidents in a single year.

After two years, that number went down to 150.

Clute says political rhetoric got away from true justice.

SYLVIA CLUTE: Three strikes, you're out, abolish parole, truth in sentencing, all of those were just slogans to play on our fear of crime to get the politicians elected.

They were not good public policy.

CHLO'E EDWARDS: You may have a student that comes in and they started a fight.

Well, the educator, if they're just focusing on the fight that the student caused and continuing on with their curriculum, well, nothing's been resolved in this instance.

However, if they take a step back and go talk to that student and say, ‘Hey, what's going on?

They may find out this student didn't eat breakfast, maybe didn't eat dinner the night before.

BILLY SHIELDS: In Virginia, going from school to court is a frequent trip, leading to broad practices described as exclusionary.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: Example of being excluded and not being repaired is suspending a young man and never letting him come back for something that could have been dealt with maybe just with three days, you know, you understand?

CHLO'E EDWARDS: So the Center for Public Integrity in 2015 reported that Virginia was a leading state in referring kids from the classroom to the courtroom.

That same data was found to be true in 2021.

BILLY SHIELDS: Restorative justice looks at collaborating to break that cycle.

CHLO'E EDWARDS: It's voluntary, that means that if two parties that need to work out a conflict, both have to agree to the process or it will not work, it cannot be mandated.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: Let's just say there's two individuals, they're playing basketball and one of the youth smack the other youth.

Now in our world, that could cause a whole thing out in the community.

How do we repair that?

How do we operate in restorative practices?

What do we do?

We pull those two individuals together, we have this individual take responsibility.

Let's talk about why you really slapped him, did it even have anything to do with him?

BILLY SHIELDS: A sometime component of this approach, which is used in Danville, for instance, is employing workers called credible messengers.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: They use those experiences to connect with those individuals out in the community.

That's another thing why we're so successful is understanding the needs and the authenticity of how we operate and how we provide services.

CHLO'E EDWARDS: And they're able to talk to the gangsters on the streets and say, “Hey, 6:00 AM to 8:00 AM, safe passage route for students.

” BILLY SHIELDS: Chlo'e Edwards knows the value of shared experiences.

Her own father spent time in prison for drug addiction.

CHLO'E EDWARDS: And being put in jail for three years, spending time away from his kids, like myself, I'm one of three, I'm a triplet, it didn't cause rehabilitation.

What it created was a cycle of drug use and then incarceration.

BILLY SHIELDS: The court system in Virginia is evolving, however.

SYLVIA CLUTE: So our juvenile courts have a lot of diversion programs.

So these are, kids get into trouble, they come into the juvenile courts, and then, there's, you know, they're processed.

And there are diversion programs that can be selected for them to go to and a good many courts in the state have restorative justice as one of those diversion programs.

BILLY SHIELDS: In Danville, as a restorative effort to divert youth from gangs, they are actually turning to esports.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: This generation is about gaming and there is employment in gaming, they give scholarships for gaming.

Our local college here has a esports team.

So in Project Imagine, we understand that we don't push youth away from their desires, we try to find a way to incorporate it that is productive.

So what we did here is we started an esports game, esports gaming team.

BILLY SHIELDS: And there's money to be made in esports.

The kids David helps are actually using that as a source of income, a creative solution aimed at beating the streets.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: And we use evidence-based theoretical principles and methods in order to improve self-efficacy and things like that, so what we're talking about is entrepreneurship, but maybe not like entrepreneurship that a 40-year-old might think of, but we're talking about things like braiding hair or art or music or audio visual.

BILLY SHIELDS: From Richmond to Danville, an idea that started with Mennonite court volunteers is sweeping departments and agencies all over the state.

CHLO'E EDWARDS: I think restorative justice can be looked at a broader level, when we talk about the concept of truth telling and reconciliation, repairing the harm caused.

ROBERT DAVID SR.: To me, restorative justice is responsibility to repair in equitable spaces.

BILLY SHIELDS: For VPM News, I'm Billy Shields.

ANGIE MILES: The nonprofit Impact Justice, which advocates for a prosecutorial reform says young people who participate in restorative justice programs are 40% less likely to repeat certain serious offenses than those prosecuted through more traditional means.

Here in Virginia State, Senator Stella Pekarsky and Delegate Dolores McQuinn sponsored legislation during the 2024 session requiring public schools to offer at least one restorative practice before considering suspension or expulsion.

Governor Glenn Youngkin vetoed that change, calling it unsafe, and adding that the Commonwealth is in a "School discipline crisis."

ANGIE MILES: Howard Zehr has been developing and promoting restorative justice principles since the 70s.

He's the founder of the Zehr Institute for Restorative Justice at Eastern Mennonite University, where he is still teaching today.

Thank you so much for joining us.

What is the short story of how you became known as the grandfather of restorative justice?

HOWARD ZEHR: Well, in the 1970s, I reluctantly got involved with this new idea that some people were doing on bringing victims and offenders together in criminal cases.

I was very reluctant because I came from a background of defense, working with prisoners and defendants.

But when I sat down and began to listen to victims and hear their stories, and hear their needs, and then when I began to see what happened, when victims and offenders came together, it just shook up my whole world.

I began to synthesize what I was reading and hearing and experiencing into a concept that I found this term restorative justice, and applied that in the late 70s, early 80s.

and then it went kind of went from there.

ANGIE MILES: But you would say that this really is a victim-centered approach, how so?

HOWARD ZEHR: What restorative justice is about, is addressing the harms and the needs that have happened and finding out whose, whose obligation they are to repair those harms.

And so the victims have got to be central in this thing.

So I spent a lot of my career trying to help remind people that this is about everybody.

It's about victims.

It's about offenders.

It's about engaging the community in this process.

ANGIE MILES: There is something in peace-loving, cultures that leans towards restorative justice.

Could you elaborate on that?

HOWARD ZEHR: I've had so many graduate students from Indigenous traditions around the world.

I've traveled around the world, and I've realized that most, most traditions, most Indigenous traditions have both a restorative and a retributive element.

I was helping people understand what were really Indigenous in a lot of ways, but in a modern context.

So yeah, I think restorative justice has a lot of resonance with many Indigenous traditions.

(upbeat music) ANGIE MILES: You can watch the full interview on our website.

ANGIE MILES: Fairfax is considered by many to be a leader in restorative justice.

It's been almost a decade since the county instituted its first diversion court.

Now these dockets, which provide for accountability, but also treatment for drugs, mental health, or veterans issues, are gaining ground all over the Commonwealth.

These special courts divert people facing criminal charges away from incarceration, and towards something that offers more hope, and possibly, greater healing.

RACHEL THORNSBERRY: I am a veteran of the US Army.

I joined in 2000 right out of high school as an 18-year-old kid, just wanting to go save the world.

And during my time, I experienced some trauma from my peers.

At the time, I didn't realize that that trauma would eventually be a ticking time bomb and what that would mean for me.

And there's so many other people that experience those traumas, people that fight for our country that see things that other people don't see.

So when I graduated from the Veterans docket in Spotsylvania, it was super important for my whole life because it was important to me to prove to not just myself, but everybody else, that this recovery road is possible.

It is fair to say that the program did save my life.

I am here sitting here talking to you today because of that choice.

STEVE DESCANO: A diversion court is, it's a problem solving court.

It's not adversarial.

It does take place in a courtroom, but it is all about all the sides, all the parties working together to try to get at the root cause of why somebody has touched our justice system and everybody working together to help that person, not punish them so that they can become the member of our community that they want to be.

We have a veteran treatment docket court.

We have a mental health court, and then we have a drug court.

We live here in Fairfax County in a community with roughly 70,000 veterans.

Veterans understand what what other veterans go through and that comradery, they want to help these individuals.

That really was a big driving force here in Fairfax.

But like anything else, once you see it working, once you see it being effective, you want to spread it out to many other people.

We in the justice system can do better.

We know that we put more people in jail and prison than any other country in the world, and yet we're not the safest country in the world.

If you really care about community safety and you really care about helping people, then you start to look at alternatives.

Our Veterans Court docket has a lot of veteran mentors and the interactions with those veteran mentors who are just volunteers who really care about their fellow veterans is really, really important in terms of keeping up with those individuals and making sure that you're on track.

There is this misunderstanding that these types of programs are somehow soft on crime, when in reality they're smart on crime.

These programs don't exist out of the goodness of people's hearts.

They exist because they work.

They help individuals lower their recidivism rate.

It creates lower crime going forward.

I've gone to a lot of these graduations and heard their stories and just the way that these individuals talk about themselves from before they were in the program to when they are now and graduated, they are so happy with where they are at, that they're such a better version of the person that they were.

It's really inspiring.

RACHEL THORNSBERRY: I am a senior at Liberty University.

I never thought that I would be able to go to college.

I have two semesters left until I graduate.

I'll have my bachelor's in social work.

I run a ministry called Help Along the Way, we help individuals who are getting out of jail, prison, people entering the recovery community, and that's really where the best feeling of accomplishment comes from, is reaching back and bringing the next person that was behind you.

It makes me so happy to see all these different counties stepping up, providing these programs.

I couldn't be happier seeing that because everybody deserves to go through a program.

Everybody deserves that help.

ANGIE MILES: Virginia has nine veterans treatment dockets.

Fairfax being the first, and Pulaski being the newest.

Loudoun County recently graduated.

its first Veterans Court participant.

Restorative justice has found its way into America's jail, schools, and courtrooms, also communities.

The concept is rooted in Indigenous traditions as well as peace-loving cultures, and is employed in many ways today.

For more stories about restorative justice efforts in Virginia, and to hear more of our interview with Howard Zehr, simply log onto our website, vpm.org/focalpoint.

Thank you for watching.

We'll see you again next time.

Production funding for VPM News Focal Point is provided by The estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown.

And by... ♪ ♪

Diversion courts are rooted in restorative justice

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep8 | 3m 24s | Special dockets offer support for veterans and others to avoid jail time. (3m 24s)

Lynchburg City Schools work to curb suspensions using restorative practices

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep8 | 3m 48s | School districts throughout the nation are shifting towards restorative justice. (3m 48s)

Reincarceration in the Commonwealth

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep8 | 3m 53s | A local jail is combating recidivism with a program that aims to rehabilitate inmates. (3m 53s)

Restorative justice in Virginia

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep8 | 7m 32s | How agencies find alternatives to punishment in the Commonwealth. (7m 32s)

Restorative justice’s Indigenous roots

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep8 | 7m 47s | Howard Zehr on his role in restorative justice movements and the philosophies’ indigenous roots. (7m 47s)

Restorative justice’s ties to Mennonite faith

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep8 | 3m 48s | Big criminal justice reform ideas are from a small campus in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. (3m 48s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S3 Ep8 | 3m 38s | A Roanoke restorative program kneads change through breadmaking. (3m 38s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM