VPM News Focal Point

Revisiting Project Exile

Clip: Season 2 Episode 13 | 7m 25sVideo has Closed Captions

Project Exile aimed to combat the notorious record number of murders in the 1990's

In the 1990s, Richmond, Virginia, became notorious for a record number of murders. Propelled by the crack cocaine epidemic, the city was home to drugs and guns. In response, Project Exile launched in 1997 and within a year, the murder rate dropped. The project also had a number of critics.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown

VPM News Focal Point

Revisiting Project Exile

Clip: Season 2 Episode 13 | 7m 25sVideo has Closed Captions

In the 1990s, Richmond, Virginia, became notorious for a record number of murders. Propelled by the crack cocaine epidemic, the city was home to drugs and guns. In response, Project Exile launched in 1997 and within a year, the murder rate dropped. The project also had a number of critics.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch VPM News Focal Point

VPM News Focal Point is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipPOLICE DISPATCH: In progress fight.

OFFICER 1: Let's go, let's clear the street.

OFFICER 2: Let's go.

ANGIE MILES: In the mid 1990s, the city of Richmond, Virginia became notorious for a record number of murders propelled by the crack cocaine epidemic that swept the nation.

Richmond became home to open air drug dealing and where there were drugs, there were guns.

JOE FULTZ: People called me Joe.

My last name is Fultz.

I was a homicide detective in the city of Richmond.

I was working in a unit called Strikeforce at the time which was a drug and gun seizure team.

During that time, there were open air drug markets all around the city, specifically, crack cocaine was a big deal.

Now, there was also heroin and marijuana but the main drug of choice back then was crack cocaine.

You saw a high level of violence during that time, homicides, shootings and other vice crimes.

A lot of money was flowing with the drug trade back then and one of the things we were tasked to do was stem the flow of the violence, getting the guns and drugs off of the street and taking the people responsible for doing the crimes.

ANGIE MILES: Richmond had seen its first triple digit homicide year in 1988 when 100 people had been murdered.

In 1994, the city hit a new high 160.

Many of the killings were related to drug wars and turf battles.

Some of those lost were bystanders who happened to be in the wrong place when the bullets flew.

DAVID M. HICKS: My name is David M. Hicks.

I was the commonwealth attorney for the city of Richmond, Virginia.

During the 90s, the number one issue in the city of Richmond was its homicide rate.

We were, I believe, number two per capita in the United States.

And then when we still talk about the 160 homicides in 1994, one of the things that also has to be remembered is that still didn't capture the entire picture of the level of violence.

MCV, as it was known then, just had such a off the charts trauma center.

They literally kept a statistic in those days of individuals who were clinically dead when they came in and they brought them back.

So our 160, which is just mind boggling, could have easily been 300 or 400 because the level of violence that was happening in the city.

ANGIE MILES: Then came Jim Comey, an assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District with his boss, Helen Fahey and a range of government agencies and private funders, Comey launched a program called Project Exile in 1997.

JOE FULTZ: Project Exile allowed us to make arrests take it to federal court, if you will.

Some of those laws are still on the books right now.

When a person has illegal gun, you're looking at extra time especially if it goes to the federal court, it's five years or more, and that helped back then to stem the flow of violence and take illegal guns off the street.

ANGIE MILES: The word went everywhere.

Get caught with an illegal gun do five years, in exile essentially, sentenced by a federal court to a mandatory minimum of five years usually served far away from home.

DAVID M. HICKS: The primary parents of Exile were Jim Comey and myself.

I was commonwealths attorney, and Jerry Oliver he was the chief of police, and he was hired by Robert Bobb the city manager for the City of Richmond.

We were the three primary creators for lack of a better term.

ANGIE MILES: Jim Comey has also been quoted giving credit to then mayor Tim Kaine.

Within a year, the murder rate in the city that had become known as the murder capital dropped significantly.

DAVID M. HICKS: So just the whole theory was, I can't stop you from getting mad over some of the scuffing your sneakers, but maybe if you don't have your gun with you immediately by the time you act on getting mad, it might be with something other than a gun that you're shooting someone with five times.

I distinctly remember probably a year or two into the program, we literally saw a slight uptick in malicious wounding charges from knives.

So all of a sudden someone's using a knife instead of a gun.

Now it sounds like a small thing, but it's like, "Oh, it's making a difference."

MAN: I was just walking down with my boy, my boy to the hotel.

ANGIE MILES: The results were not convincing for everyone.

Project Exile had a number of critics.

One of the more outspoken opponents then and now is U.S. Representative Bobby Scott.

REP. BOBBY SCOTT: And the studies are inconclusive.

At the time, Project Exile was going on in Richmond the crime rate was going down all over the state.

More in other cities where they didn't have Project Exile.

It may not have had any effect at all.

Curiously enough, one thing that is not discussed in all of this is how much did it cost?

There are initiatives we know that work prevention, early intervention, rehabilitation that we know reduce crime.

And rather than invest in those, we're discussing a thing that could be very expensive.

ANGIE MILES: In addition to the cost and questions about effectiveness, Scott objects to the mandatory minimum sentencing requirements in federal court, which he says.

REP. BOBBY SCOTT: If you look at crack where the penalties were significantly more draconian disproportionate number of people caught up in that are African American.

Similar crimes with powder are not prosecuted with the same vigor or with the same punishment.

You can have a policy that is targeted to the African American community and it tends to get passed as a good criminal justice policy.

I just think it's unfair.

ANGIE MILES: Exile defenders say that crack, unlike powder and street crime versus less public crime tend to be associated with violence, and that the effort to stop that violence is not racially targeted.

REP. BOBBY SCOTT: We ought to be looking at the cost-effectiveness of crime prevention programs.

And you know if you put the money in a lot of programs starting very early, early childhood education, after school programs, summer jobs, getting young people on the right track and keeping them on the right track those are the things known to reduce crime.

Most of them saved more money than they cost.

ANGIE MILES: After other cities saw what appeared to be success with Project Exile, it was emulated all over the country and even garnered praise at the federal level, including from several presidents.

Fultz says he believes Exile worked and can work again.

He says it's not meant to solve the entire problem of crime but it is designed to give citizens an immediate degree of protection, immediate relief from murder and street crime.

Fultz says the fight against crime should not be up to law enforcement alone.

He says, families, schools, politicians, everyone in a society, he says has a role to play in helping people make better choices and avoid crime and its consequences.

JOE FULTZ: The police are just one cog in the wheel.

Now, do we have other things to work on, yes.

Can we start at the home?

Can we start at the school is a major place.

Everybody has to be involved.

Everybody has to get on the page and say, "Hey look, we got this piece.

Let's try to put this together and see what problems we can fix and solve this problem."

Aber says Project Exile is in exile

Clip: S2 Ep13 | 17m 2s | Crime-fighting office says it's not in their vocabulary (17m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2 Ep13 | 8m 8s | With Roe v. Wade gone could lawmakers limit reproductive decisions based on genetics? (8m 8s)

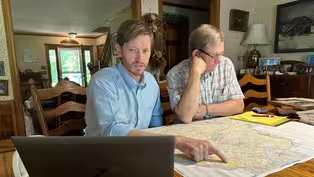

Family shows Franklin County is about more than moonshine

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2 Ep13 | 3m 46s | Father and son uncover a forgotten history about Franklin County. (3m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2 Ep13 | 2m 59s | 95-year old Herman Harrison recalls growing up in Franklin County. (2m 59s)

How Virginia's tobacco legacy endures in repackaged form

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2 Ep13 | 4m 27s | Tobacco remains a prominent part of Virginia’s culture, despite its infamous roots. (4m 27s)

Moonshining in Franklin County: Bootlegging Goes Legit

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2 Ep13 | 4m 10s | Once the moonshine capital, Franklin County is home to a thriving white lightning business (4m 10s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

VPM News Focal Point is a local public television program presented by VPM

The Estate of Mrs. Ann Lee Saunders Brown