Rhode Island PBS Weekly 7/27/2025

Season 6 Episode 30 | 22m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

Inmates learning to develop websites, 19th-century whaling logs and climate change.

We take another look at contributor Steph Machado’s story about inmates learning how to code. Then, a second look at Pamela Watts’ in-depth report on how whaling logs from the 19th century are helping modern-day scientists track weather patterns and assess climate change. Finally, we meet again Rhode Island Quahogger Jody King, who tells us everything we need to know about Quahogs.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media

Rhode Island PBS Weekly 7/27/2025

Season 6 Episode 30 | 22m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

We take another look at contributor Steph Machado’s story about inmates learning how to code. Then, a second look at Pamela Watts’ in-depth report on how whaling logs from the 19th century are helping modern-day scientists track weather patterns and assess climate change. Finally, we meet again Rhode Island Quahogger Jody King, who tells us everything we need to know about Quahogs.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Rhode Island PBS Weekly

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(lively music) - [Pamela] Tonight, giving inmates a second chance through coding.

- I'm just trying to learn as much as I can and try to change my life around basically.

- [Pamela] Then what can centuries' old whaling logs tell us about today's extreme weather?

- This kind of information for climate scientists is absolutely priceless.

- [Pamela] And everything you need to know about Rhode Island's favorite clam.

(happy music) (happy music continues) - Good evening.

Welcome to "Rhode Island PBS Weekly."

I'm Anaridis Rodriguez.

- And I'm Pamela Watts.

We begin tonight with a second look at an unlikely training program inside Rhode Island State Prison.

- Some inmates are learning how to speak the language of computers by becoming coders.

The program teaches web development and software design skills in the hopes of helping former prisoners get jobs that will keep them out of jail for good.

Last October our contributor Steph Machado took us inside to meet some of the inmates embarking on The Last Mile.

- So call func and pass in the idle.

- [Steph] Every day inside this medium security prison in Cranston.

- [Instructor] It expects an array.

- [Steph] A dozen inmates are learning to code.

- I expect you to give me an array and I expect you to give me a function.

- Dennis McDonald uses JavaScript to create a game, Rock, Paper, Scissors.

- That was pretty complicated.

- [Steph] Across the classroom, Benjamin Delacruz is often seen helping other students as they work on computers, figuring out how to program websites and games.

- These skills are enough for you to be, you know, a web developer where you're just making websites, right?

If you wanna take it further, you can learn more programming and algorithms and be a software developer and make software.

You know, the sky's the limit.

- [Steph] The class, which meets five days a week, is unlike any other educational program offered in prison in Rhode Island.

For one, the students have laptops which they get to take outside the classroom.

- When folks started going back to their cells with laptops, there was a little bit of panic.

What they were doing is continuing their work they were doing in the classroom at the desktop, and so when they go back to the classroom, it syncs back up to what they were doing.

- And there's no chance they can connect to the outside world.

- Absolutely not.

- [Steph] Wayne Salisbury is the director of the Rhode Island Department of Corrections.

He launched this program last spring after hearing about it from a state senator who got a call from an inmate who read about the program in a magazine.

It's called The Last Mile, a reference to the last leg of a person's incarceration and reentry into society, and started in San Quentin Prison in California more than a decade ago.

Now it's offered in eight states, including Rhode Island.

- It afforded folks the opportunity to learn skills and provide training to them that is relevant in today's job market, and provides an opportunity for them to be gainfully employed upon release.

The recent statistics say that 75% of the folks that are involved in this program gain employment when they're released from prison, which is astounding.

- [Steph] The ultimate goal of the program is to end the cycle of repeat offenders.

In Rhode Island, more than 40% of inmates end up back in prison within three years.

- I was out for over 15 years before this incarceration happened.

- [Steph] Delacruz first ended up in prison for a short stint when he was 18.

For years after that, he says he struggled to land reliable work.

- It's the same cycle.

I would apply for jobs.

They don't know my record yet, you know?

My resume was decent.

I would get the interview, they would love me in the interview, right?

I'd present well, I speak well, but then, you know, "We have to do this background check."

That's it.

Door slams shut.

- [Steph] Eventually he made a choice.

- I resorted to selling drugs, which is what I ended up doing.

- [Steph] He was sentenced to eight years in prison in 2021.

Initially he started trying to teach himself how to code out of books.

So when the state launched The Last Mile program, he knew he wanted in.

- I was pretty quick to jump on it because I saw that as an opportunity to continue what I had started.

I kind of saw it as, you know, as a sign, - [Steph] Web developers are in high demand and can usually work remotely, potentially reducing one barrier to getting a job with a felony record.

- This is an industry that thankfully doesn't care too too much about that.

This is, "Can you do the work?"

You know what I mean?

Do you have these skills?

- [Steph] Do you see this as a way to prevent you or your fellow inmates from ending up back here?

- 1,000%.

- [Steph] The class is taught remotely by instructors from The Last Mile.

Most of them are formerly incarcerated themselves.

When we visited back in December, it was the last class before Christmas, so the teachers surprised the students with a trivia game.

- [Player 1] History for $400.

- [Player 2] Who is Ford?

(bell dinging) All right.

(hands clapping) - [Steph] Marylouise Joseph staffs the classroom as a program facilitator.

- We hope it's giving them the tools that they need to, you know, get out there and get a job, a realistic job, you know, that's going to, you know, help them support their families and, you know, allow them to stay out of prison, you know, and make something of themselves.

- [Steph] Joseph has worked in reentry for years, so she knows how hard it can be to stay on the outside once released.

- The biggest challenges: jobs, housing.

You know, those right there.

You know, if, you know, somebody could walk out into a job and they've got a place to live, that is literally half the battle.

- Why is it so important that people get job training while they are incarcerated?

- You're setting people up for success when they get out.

You know, in many cases, folks may have had employment before they were incarcerated, but in some cases, they don't.

They may not have the skillsets.

By not having employment, it makes the struggle even more real for them when they get out.

- And when you see people come back here, what's your first thought?

We failed them?

- I think the system fails 'em and, you know, I was very naive when I assumed the acting role and I said, "Let me fix the recidivism rate" because I thought it was just the DOC.

And it's not just the DOC.

There is so much working against somebody when they get released.

So part of that is us breaking down those barriers in order to help them help themselves and not come back.

- [Steph] In Rhode Island, the recidivism rate has dropped from 51% of inmates released in 2017 returning within three years to 44% for the inmates released in 2020.

It's too soon to know if The Last Mile students in Rhode Island will have a lower rate since the program just started last year, but nationally, The Last Mile says the three-year recidivism rate for its programs is only 5%.

- It has definitely given us the opportunity to gain a career and hopefully that the program just keeps going forward and it could change more people's lives.

- [Steph] Dennis McDonald, who previously worked jobs in factories and for moving companies, hopes to get into web development when he gets out.

- I don't wanna just let this time go to waste while I'm here, so I'm just trying to learn as much as I can and try to change my life around basically.

- [Steph] You don't wanna end up back here.

- No.

- This is not happening again.

So I'm doing this hoping that, you know, it can put me that much further ahead so that I can have a meaningful career.

- [Steph] Delacruz is hoping to be an instructor for The Last Mile when he gets out, which could be as soon as this spring.

- Since being in this class and helping the other guys out, I've somehow stumbled upon I have a knack for teaching.

- [Steph] The 38-year-old's motivation?

His two daughters ages four and nine.

- I grew up without my dad, so I always said that the one thing I would never do is leave my kids how he did.

And to see myself here, that's a broken promise 'cause I left them.

- [Steph] Right now, only a small number of Rhode Island's 2300 inmates have access to this program.

There's just this one classroom set up in the medium security facility and only those who have three years or less left on their sentence can apply.

That means inmates in minimum or max can't participate and neither can women.

- I wanna be able to afford the opportunity for those that are interested as best we can, expanding that to potentially other facilities, whether it be the minimum facility or the women's facility, probably more than likely.

- I'd like it to be in every facility.

I'd like it to be offered to every individual that comes through our doors.

That's a tall order.

- [Steph] Expanding will cost money, much of which The Last Mile is willing to cover.

The nonprofit is funded by philanthropic dollars and grants, including from big tech companies.

If the program's able to expand and you had the opportunity to ask lawmakers up on Smith Hill, "Hey, here's why you should put money into this program and let us expand it," what would your argument be?

- I think the argument is just obvious.

You know, you lead a horse to water, right?

We all know the rest of that.

So that's my argument.

You know, that would be my strong argument because it's obvious.

You know, that's what we all want.

You know, we all want peace of mind.

What gives us peace of mind?

Home and heart.

That's what gives us peace of mind, and that's what these individuals are looking for.

And I hope people see that.

- Up next, could weather reports from more than 200 years ago have relevance for research into climate change today?

The answer may be yes.

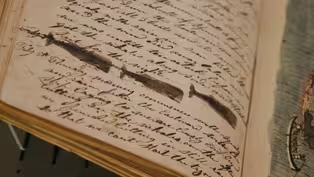

Tonight we reopen the book on a project, mining old whaling ship logs holding long-buried data about shifting winds, tides, and storms.

This is part of our continuing "Green Seeker" series.

(wind howling) Observations of winds that once buffeted this 1800s whaling ship are offering up some critical clues to climate change.

The Charles W. Morgan is an attraction at Mystic Seaport Museum.

It's the last of an American fleet that once numbered close to 3,000, and the oldest wooden commercial whaling vessel still afloat.

Ship logbooks of its many whale hunting voyages, along with hundreds of others from New England, may provide a treasure island for researchers trying to learn more about extreme weather challenges.

- Oh wow.

- [Pamela] The idea to take a deep dive into weather data from centuries' old logbooks was launched by Timothy Walker, sailor, marine historian and professor at UMass Dartmouth.

- These logbooks hold a lot of information about weather because the whalers were taking daily and multiple times a day, they're writing down the winds and the temperatures and the wind direction and wind speed and so on.

And so we wanted to know if we could extract that weather data to inform climate science.

And it turns out that you can.

- [Pamela] Walker came to New Bedford to crew on the historic schooner Ernestina.

One of his shipmates happened to be working on his PhD in climate ocean science.

- And he and I had talked about a way to do something with both of our skillsets.

- [Pamela] That discussion led to Walker fishing for weather information from the logs of local whaling ships and comparing it to the meteorology in the same coordinates today.

- They're going to places where other ships don't go because merchant and military ships, by the 1650s or so, they're following seaborne highways that they know is the most efficient way to get from place to place.

The whalers are following the whales who go to some of the most remote parts of the world's oceans.

And so they're recording weather data in places where we simply don't have any other way of knowing what the weather was like on a particular day, at a particular place, 150, 200, 250 years ago.

And this kind of information for climate scientists is absolutely priceless.

- These are the areas where we can pick up the different high-pressure systems and how they are changing.

- [Pamela] Walker's voyage of discovery resulted in a collaboration with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute on Cape Cod.

Scientist Caroline Ummenhofer's says she was all onboard.

- When Tim reached out to me six years ago about this project that there's maritime weather data contained in ship logbooks, that seemed a real boon to trying to understand how wind patterns, how pressure patterns are shifting out over the oceans.

- Ummenhofer says her research is probing the ocean's role in climate variability and its effect on rainfall, droughts, flood, and extreme weather events.

And how does this help us in dealing with climate change?

- We've analyzed 170 logbooks and we have over 100,000 daily weather entries, which is amazing.

Covering the period 1790 to 1910 with most of the data from the 1840s to '60s, which was the heyday of the New England whaling era.

We can compare that to modern-day observations that we get from satellites or meteorological stations.

It helps us put recent trends into a long-term context.

For example, one area that we know has experienced large wind changes is the Southern Ocean.

- [Pamela] Ummenhofer says there is a strong belt of westerly winds, which can carry storm systems that are churning around Antarctica.

The whalers called them the Roaring 40s.

They've shifted further south in recent decades and she says it's now more like the Furious 50s.

- It might sound strange, like what do we care about the winds over the Southern Ocean?

It's actually pretty important because rain-bearing weather systems travel on these westerly winds, and as these winds have shifted further south, they have left regions like Southern Australia and southern Africa, high and dry, and they are experiencing much more frequent drought in recent decades than they have had in the past.

- [Pamela] The Providence Public Library has some 800 whaling ship logbooks in its special collections, second only to New Bedford.

These were considered legal documents in their day.

Sailor-carved ink stamps indicate how many whales were caught on a particular date and where.

- Sometimes recording are what are called offing sketches, which is helping them to navigate.

- [Pamela] The ledgers are filled with remarkable folk art illustrations of life on the years' long journeys, eyewitness accounts of mutiny, shipwrecks, mayhem, and murder.

Walker says it's easy to become distracted by the drama while collecting the data.

He notes whalers harpooning the mammoth creatures were often pulled out to sea on what's known as a Nantucket sleigh ride.

There are also reports of tragedies in the treacherous waters as he read in one gripping encounter.

- Each whaling boat has five men.

So three boats went out to hunt whales, a storm brewed up.

They lost those boats and they lost those men.

So they lost about 1/3 of the entire crew in one storm.

- [Pamela] Yet the risk didn't deter the mariners.

Whale oil was profitable and essential for lamps and for fueling machinery of the Industrial Revolution.

- This is nice.

It says bound around Cape Horn, which sounds like a sea shanty, and it is.

- [Pamela] While the wailing logs, usually written by the first or second mate, are often digitized, archival researchers have to go online to decipher the old cursive handwriting detailing weather observations and locations.

While Walker says he enjoys the history captured in the logbooks, he now has his sight set on the science.

- As a historian, it's rare that you get a chance to do something that's so topically important and so, you know, vital to survival as a species to our learning to grapple with climate challenges today.

- Is there any way that you see that this research is ultimately gonna help communities prepare for extreme weather?

- As we have a better sense of how storms and in particular, wind patterns that are associated with extreme events, how they have changed in the past, that gives us more confidence into how they are going to change in the future.

- We can point to data and we can speak to climate skeptics and say, "Yes, this is really happening."

And we have to inform ourselves so that we're in a better position to react to a changing climate.

And that's another goal of our project is to be able to provide the tools for public policy, for homeowners along the coast to be able to deal with what's coming along the path in the 21st century regarding climate change and extreme weather events.

- Finally tonight we take another look at Rhode Island's favorite clam, the quahog.

As part of our continuing "My Take" series, we traveled to Warwick's Oakland Beach to meet a man who knows a thing or two about the mollusk.

He's been digging them up for more than 30 years.

- This is a 12-month a year job.

I do this on average between 275 and 300 days per year.

I love my job and every day is a challenge and I love a challenge.

(hands clapping) My name is Jody King and this is my take on quahogging.

(lively music) Quahog is a hard shell clam.

It's a mollusk.

In Rhode Island, we call them quahogs.

Anywhere else in the country, they call them hard shell clams.

We are unique.

It's derived from an Indian name from the indigenous people of Rhode Island, the Narragansetts.

They're one of the few animals on Earth that never stopped growing.

I've actually had them as big as my hand where you couldn't see my fingers.

(lively music) So I brought it to DEM.

They drilled a hole in it and determined that it was almost 150 years old.

You can eat a 12-year-old quahog, as well as you can eat a 150-year-old quahog.

One's just bigger and one is smaller.

I got into quahogging as a child and if you had asked me when I was a child if this would be my profession, I would've probably laughed.

But I watched a friend when I was 30 years old catch a few clams and make a couple hundred dollars in an hour and a half, two hours.

I said, "This is it for me.

I found my job."

My day generally starts about 4 o'clock before the birds are even up.

I'm up and out of bed for breakfast, feed the dogs, walk down the street to my boat, hop on the boat and go to work.

(lively music) (wind blowing) So yeah, this is when I go out early.

(dog whining) (lively music continues) For the most part, when I get out there, I know where I want to go.

When I get there, I figure out the depth of the water.

I set up my pipes and my rake, my handle, depending on the depth.

I throw them in and start pouring through the water blindly.

(engine stuttering) (water splashing) Everything for me depends on God and Mother Nature to give me conditions to move and the ability to do so.

(water sloshing) And this will have bigger stuff in it 'cause I went out of my area.

Every day is different.

No two days are the same.

I don't catch the same amount of clams two days in a row because conditions change day by day.

So I try for five, I hope for 1,000.

20.

If I get it, I'm happy.

If I don't, I go out again tomorrow and start all over.

(lively music continues) You can make chowder, you can make stuffies, you can make casinos, you can make clams and pasta.

There's a myriad of things that you can make with clams.

Every one of them is good.

I haven't had a clam meal that I didn't love.

After 30 years you'd think I'd be sick of 'em.

I still love clams as much today as I did the first time I caught 'em.

(hands clapping) My name is Jody King and this has been my take on quahogging in Rhode Island.

- That's our broadcast this evening.

Thank you for joining us.

I'm Anaridis Rodriguez.

- And I'm Pamela Watts.

We'll be back next week with another edition of "Rhode Island PBS Weekly."

And you can now listen to our entire broadcast every Monday night at 7 on The Public's Radio.

Also, don't forget to follow us on Facebook and YouTube and you can visit us online to see all of our stories and past episodes at ripbs.org/weekly, or listen to our podcast on your favorite streaming platform.

Goodnight.

(lively music) (lively music continues) (lively music continues) (lively music continues) (lively music continues)

Green Seeker: Whaling and Weather

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep30 | 7m 50s | Old whaling ship logbooks in a local library may offer up new insight into climate change. (7m 50s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep30 | 9m 50s | Rhode Island inmates are learning to code. (9m 50s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep30 | 3m 58s | Learn all about Rhode Island’s favorite clam. (3m 58s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media