Rhode Island PBS Weekly 9/10/2023

Season 4 Episode 37 | 23m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

A breakfast staple is putting refugees to work, plus one woman’s life-changing moment.

Weekly's Michelle San Miguel reports on a Providence program that offers work and training to refugees who have resettled in the state. Then, in our new continuing series, Turning Point, producer Isabella Jibilian interviews a woman whose life-changing moment came on her first day of 4th grade. A warning, this segment includes racial slurs. Finally, we revisit our story titled "Islamic Faith."

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media

Rhode Island PBS Weekly 9/10/2023

Season 4 Episode 37 | 23m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Weekly's Michelle San Miguel reports on a Providence program that offers work and training to refugees who have resettled in the state. Then, in our new continuing series, Turning Point, producer Isabella Jibilian interviews a woman whose life-changing moment came on her first day of 4th grade. A warning, this segment includes racial slurs. Finally, we revisit our story titled "Islamic Faith."

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Rhode Island PBS Weekly

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Michelle] Tonight, how a breakfast staple is putting refugees to work.

- I feel like it's a celebration to be around people who are different.

- [Pamela] Next, a critical turning point in one woman's childhood.

- He reached out his hand and walked me out of that room, and it was one of the most important times in my life.

- [Pamela] And the impact of 9/11 on the lives of two Rhode Island Muslims.

- As a Muslim woman, at that point, my whole life changed.

(bright music) - Welcome to "Rhode Island PBS Weekly," I'm Michelle San Miguel.

- And I'm Pamela Watts.

More than 25,000 refugees came to the United States during the 2022 fiscal year.

Here in Rhode Island, the number fluctuates between 100 and 345 every year.

- For many, finding a job in their new country is a daunting task.

Tonight we introduce you to a group here in Providence that's trying to change that by teaching life skills in the kitchen.

- It's a rude awakening to be dropped into American society, where your rent is due, and the rent is high.

Just so it all stays in there.

- [Michelle] Keith Cooper is passionate about helping people who've been displaced.

Years ago, while leading an education program for refugees in Rhode Island, he began thinking about a more hands-on approach to teach them about the American workplace.

- So I just started trying to figure out ways to get people outta the classroom, ways to keep it interactive relational, and then we'd go on little field trips to just go to Walmart or go to Home Depot or someplace, you know, that was work-related to get some sense of orientation.

- So how do you go from there to- - To a granola factory.

(chuckles) - Granola factory.

(laughs) - Yeah, well, (chuckles) I don't know.

There are moments I think, this is a crazy idea.

(Michelle laughs) I started with granola just 'cause, okay, I know how to do that.

That was easy.

It doesn't take much equipment.

You know, you need a oven and you need a burner.

That's it.

- [Michelle] And Cooper's idea has paid off literally, helping refugees learn valuable skills while offering them a salary.

Inside this kitchen in Providence, refugees from all over the world produce more than nine tons of chewy, crunchy, savory, and sweet clusters every year.

Inspired by his love of the band U2, Cooper named the organization Beautiful Day.

♪ It was a beautiful day ♪ - [Michelle] Since 2012, the nonprofit has helped prepare about 175 refugees to work in the United States.

Those in the program receive about 300 hours of training for three to four months.

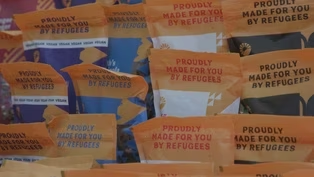

They make granola bars and more than a dozen types of granola bags, including Berry Medley Cobbler and Mango Pomegranate.

Every package states, proudly made for you by refugees.

This breakfast staple has offered a fresh start for people like Rose Ntirampeba.

- You're all set, thank you.

- Thank you.

- Have a nice day.

- The mother of five sells Beautiful Day's granola at farmers' markets.

Before she joined the staff, Ntirampeba made the snack with other refugees in the training program.

What was it like to be there alongside other refugees?

- It was very nice to me 'cause I see a lot of people from different country.

We work together, communication for them, work group, and talk about our life, where you come from, our life, how was it going over there.

- Do you eat granola?

- Yeah, I eat.

- You do eat it.

- I eat granola.

(chuckles) I eat too much.

- Yeah.

(both laughing) You eat too much granola!

So they have the perfect person selling it at the farmers' market.

- Yeah, (chuckles) mm-hmm.

- Yeah.

- This is the salesperson.

(all laughing) - Ntirampeba's become a friendly and familiar face to loyal customers, but her journey to Rhode Island was a long one.

She left her home country of Burundi, the site of an ethnic-based civil war, when she was only two years old and grew up in a refugee camp in Tanzania.

Then in 2015, she moved to Rhode Island with her immediate family.

What is that like, trying to get by in a new country while you're missing your family and your friends back in your home country?

- Ah, for that, it's okay, because when you get another country, you get another friend.

Yes.

(chuckles) It depend how the people take care of you, is you feel like your family.

Yeah.

- [Michelle] Refugees from roughly 30 countries have gone through the program, including Somalia.

Nora Ismail was born there, but armed conflict in her homeland forced her to flee.

She moved to Rhode Island earlier this year.

She says working at Beautiful Day has left her feeling hopeful.

- When I come, I work.

Now I give advice for all the refugees.

You come to Rhode Island, if they wanna enjoy or they want to become, have more confidence, come to Beautiful Day.

- This year, Cooper expects to bring in about $300,000 in revenue.

That includes sales of their hummus and coffee.

You've now been doing this for 11 years.

How do you measure the success of the job training program?

- Our primary goal is just confidence.

Try to put people in a situation where they realize, I can do this.

- But confidence is that big of a barrier?

- I think it's really easy to drop into another culture and feel, I don't know, feel alone and strange.

- You're doing a very good job!

- [Michelle] Learning English helps overcome those feelings.

- Is it hot or cold?

- This one?

- Yes.

- (chuckles) This one hot.

- Ah!

Very hot!

- [Michelle] Maliss Coletta is the director of training at Beautiful Day.

She helps refugees work on their vocabulary.

She says the training program is a springboard for full-time employment.

- You are measuring.

Once they are placed in a job, the skills that they gain from Beautiful Day is to help them keep the job.

If they are not prepared, they might be placed in a job, but they may not be able to keep it.

What is this called?

- A tray.

- And what are you doing with the tray?

- Putting on the table.

- [Michelle] Coletta knows all too well the hardships these refugees are facing.

- I spent my formative years living in refugee camps, moving from one to another, looking to be accepted as a refugee.

- [Michelle] She was born during a bloody civil war in Cambodia and fled in the middle of the night when she was six years old.

- Being a first-generation refugee, having to experience firsthand the trauma, the loss, the grief, and having seen my parents, my family also struggle, it bring me to a place where I can serve refugees to be able to help them sort of navigate life here in a new country.

- [Michelle] It's a struggle millions will face.

The United Nations estimates more than 117 million people worldwide will be forcibly displaced or stateless this year.

Born to missionary parents in Vietnam, Cooper grew up seeing the struggles many face in their own country.

- They were linguists, so they were working with indigenous people who often were not literate, didn't have a written language, were often persecuted by the nationals.

So, of course, those issues of belonging and difference are just really important to me.

Yes, have a seat, have a seat - [Michelle] Once a week, Beautiful Day invites refugees and staff members to a community dinner.

On this night, Syrian food is on the menu.

- [Staff Member] It's called fattet.

- Fattet.

- Fattet, yes.

- [Keith] You stir it all together first?

- You don't have to, the people has, you know, different ways of eating.

- [Michelle] It's an opportunity to talk with people from different walks of life behind a shared mission.

- Three days, four days.

- To ferment it.

I feel like it's a celebration to be around people who are different.

This is a gift, to be in a place where people are discovering how to communicate with each other.

- If Beautiful Day did not exist, where do you think the refugees who work in this kitchen would be working?

- Well, some would not be.

Let's face it.

Others would just have a longer journey into the workforce, and a discouraging one.

- [Michelle] Something Cooper says could easily be avoided if companies invested more in refugees.

- I think employers sometimes don't have the perspective or tools to say, you know, we're gonna build a multicultural work team where you can work with somebody who's at the beginnings of learning English.

You have to be able to make some investments in case management, in translation, in flexibility.

- [Michelle] His bottom line?

- I think refugees make really great employees.

If employers make the effort to employ them, I have no doubt that they end up with, you know, amazingly good workers.

(bright music) - Next up, can you think of one moment, event, or a situation that dramatically altered the course of your life?

Tonight we debut a new continuing series called Turning Point.

In this premier segment, producer Isabella Jibilian interviewed a woman whose life-changing moment came on her first day of school in the fourth grade back in 1968.

And a warning, this segment includes racial slurs.

- My name is Raffini, V. Raffini, and I'm gonna tell you about when I went to Prospect Street School for the first time.

It was '68, right after Martin had been assassinated.

- I just wanna do God's will.

- So I was around 9, 10.

(gentle music) (gentle music continues) We were moved to the projects, and we were finding that the people that lived in the projects didn't really want these Black families that were now living up there.

No one from my family was in my school.

There was only one other Brown girl that was there.

When I got into the class, the students were there but the teacher wasn't there.

I looked around, I saw an empty desk.

There was nothing on the desk to identify if it was someone else's desk or not.

I sat in that desk, and a young kid came in and said to me, "Get out of my chair," he called me the N-word.

"I'm sick of you niggas coming to the school and thinking you're taking over."

And I remember being shocked and thinking he's gonna get in trouble for saying this, and wondering why no one is saying anything, they're just looking at me and looking at him.

And he said it again, "I'm sick of you niggas," and he pushed me.

And when he pushed me, I felt like my dress went up and people saw my underwear, and so I was embarrassed, and I fought him out of embarrassment.

While I'm hitting him, the teacher walks into the room and she smacks me in my head from behind.

And I just pushed my hand back like that and continued to fight the kid in front of me.

And when I heard her start to scream, I thought, oh my God, I've just hit an adult, my mother is going to kill me.

But at the same time, I'm still punching him because I don't know how to act or react to what's going on, and I'm just scared and embarrassed.

And thank God one of the young kids who, when this first started to happened, ran out of the room to go get the principal.

The principal's name was Abraham Asermely.

So as he returns with the principal, the teacher's standing there screaming, "Get her outta my class!

I don't want her in here, she's a troublemaker!

She can't come back in here!"

And the principal's saying to me, "Tell me what happened, what's wrong?"

And I can't.

I can't talk because I'm too busy crying, I'm (hyperventilates) trying to catch my breath.

The principal just puts his hand out and takes my hand and brings me to the hallway.

But somehow, in my heart, I knew that this was a caring hand.

We got to the end of the corridor, and he stopped and he said, "Please tell me what happened."

And I told him the whole story, and I could see his face just feel so bad.

And he said, "Unfortunately, this is the only fourth grade that we have here, but don't worry about it.

I'm gonna take you to my office.

We have a secretary there and a receptionist.

We'll teach you."

I felt like I was just saved.

So he brought me down and introduced me to them and told them the story, and they said, "Don't worry about it, you just come here when you come to school, and we'll have your work ready for you."

Taught me my schoolwork, but they also taught me how to answer a phone properly in the office.

(bell rings) I had the privilege of ringing the bell to send the kids out for recess and bring them back in.

I learned how to use a copy machine, which back in that day was called a ditto machine.

Sometimes I'd go home with ink blots on my shirt.

But I was proud of the work that I was doing.

And I, you know, graduated from the fourth grade without being in the fourth grade and went on to another school.

I became an educator.

I was actually a teacher for 25 years.

I think we need a shovel for that.

It was up to me to hire the worker who was going to work with me in the youth garden.

Thank you.

And so I saw somebody's resume, and I called the number and I started speaking to this young woman named Ellen.

And we get to the final question, and I look at the top to address her by her first and last name.

And it says Asermely.

And I'm thinking, no way, (laughs) because it's 50 some odd years later.

"Ellen, I have to ask you something.

Do you have anyone in your family who was in education years ago?"

And she said, "My grandfather.

My grandfather Abraham."

I told her the whole story about it, and she's got tears and I've got tears 'cause I can't believe I'm speaking to the granddaughter of a man who made a difference in my life, a big difference, when you stop to think about it.

If Abraham Asermely had not taken me out of that room and I had to deal with the teacher not wanting me there and a child who did not want me there, I'd have been a very angry Black girl, and I'd have grown up to be a very angry Black woman.

(inspiring music) - We're gonna plant them all together.

Sound good?

- It's a blessing working with Ellen.

I say, "How do you think your grandfather feels, you know, us working together, doing stuff together?"

He's beautiful.

Pollinate, baby.

And I'm like, "I think that your grandfather is looking down and very, very pleased at what he sees."

Thank you, Abraham Asermely.

- And our thanks to V. Raffini for sharing her story.

Finally, this week marks the 22nd anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

While many Americans remember a moment of national unity following the event, others, as we first reported back in 2021, experienced prejudice for the first time in their lives.

With all of the hijackers identified as Muslim, the tragedy cast a harsh spotlight on people of that faith here in America.

Tonight we meet again two Muslim Rhode Islanders who talk about life pre- and post-9/11.

- My name is Reem, I was born in Kuwait.

I moved to Rhode Island when I was 12.

Growing up in Rhode Island, when I first came here, it was a little bit of a culture shock.

Maybe not so much that because it was Rhode Island, but it was just a completely different lifestyle.

Not many people really knew I was Muslim originally because I kinda looked, I guess I looked Spanish in some ways.

You know, I had curly hair and didn't wear the hijab then.

I don't think people even paid attention to Islam, period.

Growing up here, I don't think people ever really even asked me.

You know, it wasn't a conversation.

(gentle music) - My name's Abul (indistinct).

My mom is half Jordanian, half Syrian, my dad's Syrian, and I was born in Boston.

Honestly, I've never really looked at myself as any different than anybody else.

I never felt like an outsider for the most part.

You know, I've always been surrounded by great friends, whether they're Muslim or not, and I've always felt included and, like, you know, part of a community and part of a family.

- Being a Muslim is my life.

It's my lifestyle.

It's everything.

Everything day-to-day involves me being a Muslim.

Dude!

When I wake up in the morning, I wash up for prayer.

Before we eat, we say, "Bismillah," which is the name of God, you start a meal.

So everything in our life revolves around being a Muslim.

- As sappy as this is gonna sound, I think my religion gives me purpose.

You know, I don't think I'd be even half the person I am today if it weren't for my religion.

In a sense, it gives you something to work towards.

I'm a very goal-oriented person, you know?

And believing that, you know, there is heaven, there is hell, believing that God's always watching just gives me purpose, you know?

(tense music) - 9/11 was one of the scariest days in my life.

I remember it vividly.

It was my second year in college.

I remember chaos.

I went home, turned the TV on, and it was the footage of the first plane going in.

I'm getting goosebumps talking about this.

And then the second plane hitting the tower, and it kept going over and over and over.

And then finally a terrorist attack.

I feel like it was the first time I ever, maybe it wasn't, but to me it was the first time I ever heard the word terrorist so much in my life.

And then right next to it, Muslim, Muslim.

And as a Muslim woman, at that point, my whole life changed.

It was scary going to work, it was scary going out, it was scary leaving my house.

At that point, I was wearing a hijab, and I had people follow me, yelling, "Get out of our effing country, you terrorist!"

just because I looked like the other now.

- You know, if you're saying about, like, the bombers that bombed 9/11 as defining Islam, then that's the same as saying, like, KKK defines Christianity.

You know, it's not accurate, those are just a small minority of extremists.

'Cause when you look at the percentage of Muslims in the world relative to, like, ISIS members, Taliban members, it's a very small fraction.

It's there, but it's small, and that would just be the extremist minority - I feel even after September 11th, a lot of people looked into Islam and learned a lot about Islam, and turns out it was not such a devil, it was not such an awful religion.

The older I get, the more I learn about Islam, the more I dig deep, I love it more and more.

It is truly, it's beautiful, to say the least.

- That's our broadcast this evening.

Thank you for joining us.

I'm Michelle San Miguel.

- And I'm Pamela Watts.

We'll be back next week with another edition of "Rhode Island PBS Weekly."

Until then, please follow us on Facebook and X and visit us online to see all of our stories and past episodes at ripbs.org/weekly.

Or you can listen to our podcast on your favorite streaming platform.

Goodnight.

(bright music) (bright music continues) (bright music continues) (bright music continues) (bright music continues)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S4 Ep37 | 5m 49s | A look at life as a Muslim American, before and after 9/11. (5m 49s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S4 Ep37 | 9m 17s | A breakfast staple is putting refugees in Rhode Island to work. (9m 17s)

Turning Point: Raffini’s First Day

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S4 Ep37 | 7m 29s | The story of a life-changing first day of school. (7m 29s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media