Rhode Island PBS Weekly 9/1/2024

Season 5 Episode 35 | 23m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

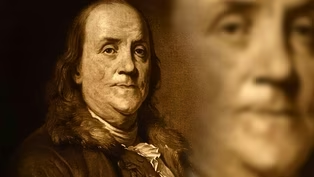

Home schooling in Rhode Island and Benjamin Franklin’s enduring legacy on public education.

We revisit Michelle San Miguel’s in-depth report on what’s behind the rise of parents home schooling their children in Rhode Island. Then, we take another look at the enduring legacy of Benjamin Franklin in one local town. Finally, we return to Rose Island, where producer Isabella Jibilian introduced us to a professor who is catching birds in the name of science.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media

Rhode Island PBS Weekly 9/1/2024

Season 5 Episode 35 | 23m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

We revisit Michelle San Miguel’s in-depth report on what’s behind the rise of parents home schooling their children in Rhode Island. Then, we take another look at the enduring legacy of Benjamin Franklin in one local town. Finally, we return to Rose Island, where producer Isabella Jibilian introduced us to a professor who is catching birds in the name of science.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Rhode Island PBS Weekly

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(gentle music) - [Michelle] Tonight, why more and more families in Rhode Island are homeschooling.

- I see that they get so much more of a benefit being home than if they were in a public school.

- [Pamela] And one founding father's enduring gift to a Massachusetts community.

- [James] I think he was hoping that somebody in this town would prefer sense to sound.

- Then we meet the birds of Rose Island.

(lighthearted music) (lighthearted music continues) Good evening, and welcome to "Rhode Island PBS Weekly."

I'm Michelle San Miguel.

- And I'm Pamela Watts.

As the school year begins, many parents are considering their options for the coming academic year.

- And there's one choice that's become increasingly common: homeschooling.

As we first reported in May, census data shows the pandemic sparked a nationwide rise in homeschoolers.

And we found hundreds of families in Rhode Island turned that COVID experiment into a way of life.

- People's eyes have been opened to what is possible, how learning can be done differently.

"During the spring and summer months, Adam also loved to dig in the dirt."

- [Michelle] Janet Kasenga living room functions more like a classroom.

- 15.

- [Janet] There you go.

- [Michelle] Her 6-year-old daughter, Lucy, practices her multiples of five here as she hops onto the right answer.

- [Janet] An adjective.

- [Michelle] It's also where Kasenga's 9-year-old son, James, learns the different parts of speech through a game of Mad Libs.

- And their feathers great for making Legos.

He's really into "Minecraft."

So he is got "Minecraft" Mad Libs.

And it asks you, you know, put down a noun and an adjective and a verb.

And at the beginning, he struggled with it.

But what I did is I sat on my couch, and I'd look at the room, and I'd say, what's that TV?

Like, describe the TV.

It's a rectangle.

It's black.

7 times 7?

- 49.

- Okay.

- [Michelle] By teaching her son at home in a relaxed, fun way, Kasenga says she helped him learn faster than he would've in a traditional school.

- What comes in between 10 and 20?

- [Lucy] 15.

- [Michelle] Kasenga began homeschooling during the pandemic.

The mother of three says the biggest appeal is getting to customize her children's curriculum.

She purchases them online.

- It can be so overwhelming of how much is available out there for curriculums that I just picked one.

(laughs) - If not for the pandemic, do you think you would still be homeschooling?

- We would not be homeschooling.

I had asked my husband, when my oldest was two, if I could homeschool, and he said no.

He wanted him in school.

And then once the pandemic hit, I knew it was something that I had always wanted to do, but then my husband didn't have any issues with it, because we didn't want him in school, or at public schools with masks.

And then we didn't want him on the computer either.

- Now a lot of homeschoolers are moving away from something.

- [Michelle] Melissa Robb is the advocacy director for ENRICHri, the largest secular homeschooling organization in the state.

She says many parents were frustrated watching their children struggle with remote learning.

- They saw that that wasn't working, and they just said, we need something else.

- It gave people a real chance to regroup and reassess their family and have that bond that they didn't know they were missing.

- [Michelle] Robb helps families interested in homeschooling.

So does Jen Curry.

She is the state coordinator for the Rhode Island Guild of Home Teachers, a Christian-led support group for homeschoolers.

They say there's one main message they've heard from many parents who began educating from home after COVID hit.

- I always wanted to homeschool.

I didn't know how, or I didn't take the time to figure out how- - It was the catalyst.

It was the jumpstart.

- Yeah.

- The number of homeschooled students in Rhode Island surged during the pandemic.

It's declined since its COVID era peak but is 67% higher than pre-pandemic.

We asked Rhode Island Education Commissioner, Angelica Infante-Green, about the uptick.

That's a really large increase.

What do you make of that?

- Yeah, so it's pretty aligned with the rest of the nation.

I would rather that they be in our school system, but I think parents make different kinds of choices for different reasons.

Many of the parents are now working remotely, and many of them prefer the convenience, prefer the way that they teach their kids.

- James Dwyer, professor of law at William and Mary, has been studying home education for decades and co-authored a book on the subject.

Are you seeing a shift in why parents are choosing to homeschool?

- I think people that had strong religious convictions that would support homeschooling were already doing it pre-pandemic.

So the new people are mostly not doing it for that reason.

It's mostly that they have enjoyed the educational experience and the side benefits of greater freedom, flexibility.

You can do it while you're traveling.

- When you are done, you're gonna do this page.

It's the same thing that you did yesterday.

- Janet Kasenga says religion and politics did not factor into her decision to teach at home in East Greenwich.

She worries about school shootings and bullies.

She and her husband agreed that she teach their children while he works outside of the home.

You live in East Greenwich, which has one of the best school districts in the state.

People move here for the schools.

Why not take advantage of that?

- We did move to East Greenwich for the public schools when we thought we were gonna be putting them in public school.

I see that they get so much more of a benefit being home than if they were in a public school.

- [Michelle] But Infante-Green says there are many benefits to having kids in school that can't be replicated at home.

- Our concern, because we saw this during the pandemic, is the kids socializing, right, the kids having the interactions.

Because school is about the academics, but it's the social-emotional piece as well.

- What did the bee do to tell the other bees where the food was?

- So it did a special dance, like- - What's the biggest misconception that people have about families who homeschool?

- That we aren't social.

(laughs) - And you would say what?

- We're too social.

(laughs) - Is that Ancient Box?

- On this day, Kasenga's children were playing "Pokemon" with other homeschoolers.

Kasenga says many families form close relationships with one another.

It's a way for both parents and children to develop friendships.

The growth in homeschooling since the pandemic is the latest part of a long-term trend.

There are nearly 1,400 more students being homeschooled in Rhode Island now than there were in 2013.

What do you think the increase in homeschooling says about the quality of public schools in Rhode Island?

- I don't know if it actually says anything related to the quality.

It's not only in Rhode Island.

It is a nationwide increase that we saw happen during the pandemic, and in many places it has not gone down.

- [Michelle] Commissioner Infante-Green says the growing group of homeschoolers is affecting funding for local school districts, but it's hard to identify the full extent.

- Even if you lose, let's say, 20 kids, that's a classroom.

But you don't usually lose them all in one class, on the same grade.

You lose two here, three there.

So you feel the financial impact, but you can't actually consolidate or figure another way out to budget, because it is not all in one shot.

- [Michelle] As more parents nationwide opt to educate at home, Professor Dwyer wants lawmakers to tighten regulations.

He's worried about parents who have a history with child protective services, or CPS.

- You would just check CPS records and make sure this isn't a parent who's, you know, seriously CPS involved and perhaps removing the child from school for that reason.

There's a huge downside potential in the absence of any kind of state oversight, that some children are terribly disserved by the practice.

- [Michelle] Parents don't need to have a teaching certificate to homeschool in Rhode Island.

They have to agree to provide thorough and efficient instruction.

Dwyer says that's not enough.

- Parents ought to have accomplished something academically themselves, either high school diploma or a GED.

I think, you know, if you can't complete that minimal academic program yourself, then entrusting you completely with the education of your child is unwarranted.

- Today's noon dinner was codfish hash.

- [Michelle] Amanda Campbell says more families are discovering what she's long loved about homeschooling.

- We refer to ourselves as secular homeschoolers.

So we don't teach from a Christian worldview.

We teach very open.

All knowledge is encouraged and open to my kids.

- [Michelle] She began educating from her home in Cumberland a decade ago when her oldest daughter was five.

- I just kept looking at her, thinking like, I don't wanna put you on a bus and send you away for the whole day and miss the joy, really, of watching you learn.

So let's put the big one in the middle.

- [Michelle] One of Campbell's philosophies is letting her two children, 8-year-old Elowen and 15-year-old Willow, lead with their interest while working to mastery.

- [Instructor] So 3 times 3 is 9.

- [Michelle] On this day, Willow needed help multiplying decimals.

- Multiplying by a 10th is the same as dividing by 10, right?

- [Michelle] So she turned on a video tutorial to get up to speed.

- This is a pretty easy one.

- [Michelle] Meanwhile, Elowen was in the kitchen practicing long multiplication.

- In the hopes of finding the- - [Michelle] Campbell's husband works full time while she focuses on teaching her daughters.

She says people often assume only wealthy people are homeschooling.

- We have lots of friends who consciously choose to live in smaller houses, in less nice neighborhoods, because they don't care about the school system, so that they can live on one income, so that they can homeschool.

- [Michelle] Campbell offers her daughters the option to go to a traditional school, but neither one is interested in it right now.

- We're different.

We're quirky.

We like to learn.

We like to do weird things.

Right now, I'm really into science and nature, specifically like biology and also in, like, the marine field.

So that's definitely something I've explored a lot.

- If I'm in school, I'd be stuck doing the same stuff that all the other third graders are, 'cause, like, it's hard to teach each, like, different people to do different maths at the same time.

- [Janet] Eggs are stored here while they are waiting to hatch.

- [Michelle] Back in East Greenwich, Janet Kasenga also says she hasn't ruled out eventually sending her kids to public school.

- I think my husband would like them in school by sixth grade.

If it goes with that, my son will be in school in two years.

My daughter, you know, she wants to be with us, so her opinion might change in like a year or two, but right now she says, "I don't ever wanna go to school.

I wanna stay homeschooling."

- [Michelle] Commissioner Infante-Green says she'd like to hear from homeschooling parents who are considering putting their children in public school.

- If there are things that would bring them back into the system, we would love to hear it.

We would love to hear what those things are and try to provide them as much as possible.

- We turn now to a founding father and one New England town's library.

Just over the northern Rhode Island border sits Franklin, Massachusetts, named more than 240 years ago in honor of Benjamin Franklin.

The great American statesman decided to send a present to the townspeople.

As we first reported back in November of 2022, while Franklin's gift was not what the citizens had originally hoped for, it would ultimately influence the founding of public education in America.

- People always wanna see the books, and they wanna touch them, and they wanna know if I've ever touched them.

It's almost like a sacred artifact, sort of, in town.

- [Pamela] Reference librarian Vicki Earls says this historic collection of books is so precious, it is kept under lock and key in a glass display case.

- This is it.

This is our baby.

- [Pamela] The town of Franklin, Massachusetts, treasures these books from the 1700s, because they are the genesis of the first and oldest public free-lending library in continuous operation in America.

A revolutionary idea at the time, the volumes were a gift from famous Patriot Benjamin Franklin.

- So he was a writer, a printer, a publisher, a scientist, an inventor, diplomat, a statesman, and he knew a lot about a lot of things.

- So today, we would call him a major influencer.

- Oh, absolutely, yes.

(laughs) He was a rock star.

- [Pamela] He was so popular, in fact, there are 31 towns in the United States today named after Benjamin Franklin.

But Franklin, Massachusetts, was the first.

- And this happened in 1778 when the town was founded.

A document was presented to the Mass state legislature for naming the town.

And somebody along the way crossed out the original intended name, which was Exeter, and wrote in Franklin.

- [Pamela] Franklin's community leaders may have had an ulterior motive for bestowing the honor, according to longtime historian James Johnston.

- Well, let me tell ya about that.

The local preacher of the congregational church decided that if they gave the honor to Dr. Franklin that he would give them a bell for their new meeting house, maybe one of Paul Revere's specials.

You know, that would be nice, a nice bronze bell.

- The bell request for the church steeple was engineered by powerful minister, the Reverend Nathanael Emmons.

Benjamin Franklin replied by sending the now-historic collection of books instead.

They were loaned out from the congregational church and various other buildings around town until the Franklin Library was built in 1904.

So why did Benjamin Franklin send books instead of a bell?

He explained in a letter to the town, and one line is inscribed on his statue outside the library.

He reasoned, "Sense being preferable to sound."

- Well, what he meant was, you know, would they rather know something of value, or do they just wanna listen to the ding-dong in the steeple?

I guess that's what he had in mind.

- One of the biggest part of the collection is the works of John Locke, and this is the time, the time period in history of the Enlightenment.

And John Locke, his theories, his political theories were a big part of that, the person that sort of came up with the theories of all people having the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

That's one of his concepts.

And a lot of what he wrote ended up in the constitution, almost verbatim.

- [Pamela] There is another chapter to this story.

Turn the page forward a few years, and a Franklin farm boy borrows these books.

- He was born and raised here.

He was mostly self-educated, and mostly self-educated through the Benjamin Franklin collection.

- [Pamela] That student was Horace Mann, considered the father of public education in America.

- He believed that all children have the right to education and that education should be tax-supported.

- Not only public education for white people, but he thought that Native Americans, people of color, women should have the equal opportunity to secure a good education.

And when he became the president of Antioch College, he opened the doors to women, to Native Americans, to people of color, all on an equal basis.

- Unfortunately, Benjamin Franklin never got to visit his town in Massachusetts.

He died in 1790, shortly after donating the book collection.

What do you think Ben Franklin would have thought of his namesake town?

- I think he would be happy.

Established a very nice home for his books, and I think that he would've been happy to know that his books started something very, very positive.

I think he was hoping that somebody in this town would prefer sense to sound.

- A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

That's especially true of our final story tonight, part of our continuing series Green Seeker.

In the summer of 2022, we visited the shores of Rose Island, where a Salve Regina professor captures birds in the name of science.

(gentle music) - This bird is actually fairly fat, so it's doing pretty well.

My name is Jim Chace.

I'm a professor at Salve Regina University here in Newport, Rhode Island.

And what I've been doing over the course of my career, over 20 years, is banding birds as a way to look at populations and how populations change over time.

(gentle music) The first instance of bird banding in this country was John James Audubon, who captured a phoebe on its nest, and it was with his bare hands, 'cause they're close sitters.

And he tied a little string around its leg.

And lo and behold, that bird came back to the same nest the next year.

In a sense, that's what bird banding is.

You're banding birds in a particular location, and you're most likely to find those birds, if they survive, in that location the next year.

So we're gonna go check the nets.

I've got one net here and then four others.

The night before, I put the mist nets up in locations where I think that the birds are gonna fly.

And I put these in the same place each week.

And then right before dawn, I open the net up, and these are such fine nets the birds really can't see them.

And they've been flying back and forth through these little corridors.

There's been nothing in their path.

They don't even think about it.

It'd be like if someone put a net in your doorway.

Oh, here, we got a bird here.

So the bird just sort of gets caught like it's almost in a hammock as it flies straight in.

And it doesn't get injured, 'cause it sort of sits there calmly, usually.

I check pretty often.

So no bird is hanging for too long.

It's just a matter of very gently backing them out of the net they just flew into.

And there's a song sparrow, another juvenile song sparrow.

I put it into a little bag, and that holds the bird securely until I can process it back at the banding station.

I bring it back to a central banding station where I have all my tools, and it's in a safe place away from, you know, distractions or where the bird could get injured.

This is one of the birds, the Carolina wren, that has been expanding its range north, presumably with climate change as a part of it.

Wouldn't have found on this island or in Rhode Island, really, 30 years ago.

And here they are breeding, and successfully breeding.

We've got these Fish and Wildlife Service bands.

Each are uniquely marked so that each bird has its own unique number.

Unfortunately, if the bird was to hit a window or died, and someone found it, and they reported the band number, we would know, I would know it came, where it came from here and where it went, and they would, the person who found it would know where it was last banded.

So those little bits of information are just critical.

A recent study by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which came out about two years ago, showed through a variety of different levels of evidence that songbirds, well, birds in general, but songbirds especially, are in significant decline since 1970, about 30% fewer birds.

So when you think about that, 30% fewer birds, if you're sitting here, and you're listening to the birds singing, if you were here in 1970, there'd be 30% more birds singing.

It's billions of birds lost.

And we have lots of ideas as to why those birds are being lost.

(gentle music) So when the Carolina wren begins to show up in Rhode Island several years ago, that's a signal that climate change is having an effect, and birds are beginning to move and change their ranges.

So this is the American goldfinch.

They're just a brilliantly patterned bird.

(bird squawks) And feisty.

One of the first things I measure very quickly is the wing cord, which gives an idea of body size.

Because birds are different body sizes, and their body size to weight ratio is an important index of their health.

The last thing I measure is their mass, because that's the place where the bird's most likely to escape.

I'll get a weight, and then let this guy go.

In between those times, I'm looking at measures of the bird's age and sex.

If it's a female, in the summer, I can tell you if she's sitting on eggs now or her eggs are basically, she's done sitting on eggs, and she probably has young out of the nest.

So I blow on the bird's belly.

What they get is they'll get a brood patch.

They'll lose the feathers across their breast, and that's what they can sit on the eggs with.

Birds hold a special fascination for me, because they're colorful.

They're out during the daytime.

They sing.

You can identify them by their songs and their calls.

And then the birds become like the classic canary in a coal mine.

They become a bellwether for the environment.

So they can tell us a lot about what's going on.

Even before we notice that there's environmental changes happening, the birds begin to tell us.

- And that's our broadcast this evening.

Thank you for joining us.

I'm Pamela Watts.

- And I'm Michelle San Miguel.

We'll be back next week with another edition of "Rhode Island PBS Weekly."

Until then, please follow us on Facebook and X, and you can visit us online to see all of our stories and past episodes at ripbs.org/weekly, or listen to our podcast on your favorite streaming platform.

Goodnight.

(lighthearted music) (lighthearted music continues) (lighthearted music slows) (lighthearted music brightens) (lighthearted music fades)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep35 | 5m 57s | A look at Benjamin Franklin's gift to a local town that impacted education in America. (5m 57s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep35 | 12m | Why Rhode Islanders have stuck with home schooling post-pandemic. (12m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Ocean State Media