The Hajj

Episode 4 | 54m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

Premieres Tuesday, December 23 at 9/8C

One of the five pillars of Islam is that each believer is called, at least once in their lives, to make the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage that starts and ends in the holy city of Mecca located in today's Saudi Arabia. The journey recreates Muhammad's own path as the native son returned to his tribal home as the leader of a vibrant new religion.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.

The Hajj

Episode 4 | 54m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

One of the five pillars of Islam is that each believer is called, at least once in their lives, to make the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage that starts and ends in the holy city of Mecca located in today's Saudi Arabia. The journey recreates Muhammad's own path as the native son returned to his tribal home as the leader of a vibrant new religion.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Sacred Journeys

Sacred Journeys is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

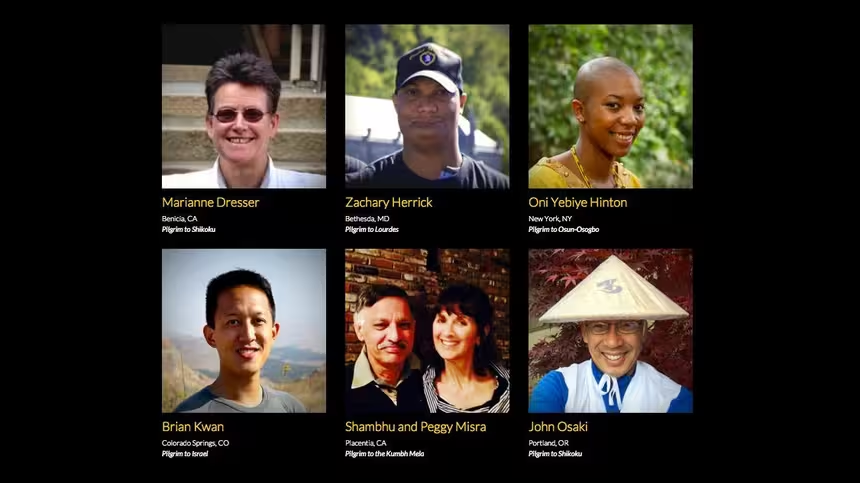

Meet the Pilgrims

Meet pilgrims from the Hajj, Shikoku, Jerusalem, Lourdes, Kumbh Mela, and Osun-Osogbo pilgrimages.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipBRUCE FEILER: I'm in the Arabian Desert, home to one of the great pilgrimages in the world, where for thousands of years people have come to answer the call of Abraham and celebrate the worship of one God.

Coming to Mecca on the Hajj is a duty and privilege for all Muslims.

WOMAN: I don't want to get distracted by the crowds.

MAN: I truly was alone with God in a sea of five million people.

FEILER: For outsiders, rare access to an arduous and emotional journey.

MAN: It was a test: Do you trust God more than anything else?

FEILER: But can these American pilgrims find what they're looking for?

Today, organized religion is more threatened than ever, yet pilgrimage is more popular than ever.

I'm Bruce Feiler.

In this epic series, I traveled with American pilgrims on six historic pilgrimages.

I bathe in the rivers of India, dance in the heart of Africa, cleanse in the waters of Lourdes, trek through the temples of Japan, and walk in the footsteps of prophets in Mecca and Jerusalem.

I attend some of the most spectacular and moving human gatherings on earth.

And I ask, what can these journeys tell us about the future of faith?

FEILER: Muslims make up almost a quarter of the world's population-- 1.5 billion people.

One of the five pillars of Islam is that each able-bodied believer is called, at least once in their lives, to make the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage that starts in the city of Mecca in today's Saudi Arabia.

The Hajj is the iconic pilgrimage on earth.

Millions of people gather in one place for five days and strip themselves of their worldly possessions.

But even as they reconnect to the past, pilgrims must confront contemporary tensions over politics, modernization and gender.

For a group of pilgrims around Boston, the question is, will these modern-day concerns overshadow their ability to seek redemption from God?

(chanting) In a few hours, these novice American pilgrims will leave for the Arabian Peninsula.

First, they need a briefing.

Like many pilgrimages, the Hajj focuses on asking God's forgiveness for human failings.

Ismail Fenni is a local imam who takes pilgrims every year.

So walk with the crowd until you get to this area and then you begin your first circuit.

KHUDAIRI: I don't want to get distracted by the crowds, by the crushing.

Well, hopefully I won't get crushed or trampled on.

The closer you get to the Ka'aba... FEILER: Tala Khudairi is an executive in higher education.

I want to be able to stay focused on the intention of why I'm there, getting closer to God and asking for forgiveness and being fully in the present moment.

FEILER: Husam Ansari is an ophthalmologist with a busy local practice.

ANSARI: I don't know that I have felt a spiritual pull to it.

This is a life milestone that has been engrained in me as something that I need to do, something that I have to do.

FEILER: Husam's wife, Amira, is the Muslim chaplain at Wellesley College.

AMIRA QURAISHI: Our processes in approaching this trip are different.

Husam is planning, he's writing lists.

And for me, just absorbed with thought and it's kind of wearing me down.

And I'm wondering when I'm going to have the energy to follow everything he's written on his list.

FEILER: Syed Muhammad Talha is an app designer who grew up in Saudi Arabia and moved to the United States as a teenager.

He's just been through a painful divorce.

Part of me wanting to do Hajj was to have a clear conscience of what had just happened.

What I went through was a big deal and I just want to ask God for forgiveness and just help me move on.

Please get on the bus so I can get a head count.

FEILER: The pilgrims have been preparing for this day for months.

Their friends and family gather to wish them farewell.

Jack Lindsay is a software engineer from Worcester, Massachusetts, who converted to Islam in his 20s and is making his first trip outside the United States.

JACK LINDSAY: I probably made a terrible decision when I was young to vow I wasn't going to go out of the country until I went to Hajj.

So I didn't know that it's going to be 28, 29 years later.

If you can think yourself of something that you really, really want, but you had to wait 28, 29 years.

Yeah, that's what I'm feeling right now.

FEILER: Pilgrimages, by their very nature, are about expectations and what happens when those expectations meet reality on the ground.

I've come to the gateway for many pilgrims, the seaside city of Jeddah.

It's one of Saudi Arabia's oldest communities, and sadly, it's the closest I can get to Mecca.

So if I got on the bus, I would be stopped, they would actually ask me?

They do go through everyone's passports on the way in.

FEILER: I'm meeting with Anisa Mehdi, a journalist and filmmaker from New York who's Muslim.

ANISA MEHDI: The area of Mecca and its surroundings, the area where the Hajj takes place, are considered sacred precincts.

FEILER: Saudi law allows only Muslims to enter Mecca and its surroundings.

So Anisa will be my proxy.

A veteran reporter of the Hajj, she will travel with our pilgrims and keep in touch via Skype.

It's another example of how technology is opening once hidden pilgrimages to the world.

So what do you say to someone when they're about to go on the journey?

Goodbye, God speed?

Tell me what you say.

You say, "May God accept your Hajj."

May God accept your Hajj.

Okay, keep in touch, we'll talk soon.

FEILER: Anisa joins the Boston pilgrims in Medina, Islam's second holiest city.

It was here that the Prophet Mohammad set up the first Muslim community in the early seventh century.

Many pilgrims begin their journey here to pray and prepare for the upcoming trial of body and spirit.

(speaking Arabic) To help me understand what the pilgrims are experiencing, I'm meeting Imam Johari Abdul-Malik, an American scholar who's made the Hajj multiple times.

What's the role of Medina?

It's not just visiting Medina, people go to visit their Prophet.

To be where he was, to live where he lived, and to ask for God's mercy.

In many ways, the journey to Medina has this back story of how Islam got started.

FEILER: Mohammad, born to a prominent tribe but orphaned as a boy, became a successful merchant, traveling a network of trade routes that brought him into contact with multiple faiths.

AMIRA BENNISON: The Prophet Mohammad grew up in Mecca and during his early life, he gained a lot of experience of the religions around him, the paganism of his hometown Mecca, but also Judaism and Christianity.

FEILER: At age 40, while praying in a mountain cave, Mohammad said he was visited by an angel who brought revelations from the same monotheistic God worshiped by Jews and Christians.

Mohammad's newfound beliefs attracted followers, but also hostility, so he fled to Medina.

Everything the pilgrims do here connects them with those early, vulnerable days of the faith.

The Quba Mosque is one of the oldest in the world, its cornerstones said to have been laid by Mohammad after he settled here in 622.

LINDSAY: To know that the Prophet came here every Saturday is just amazing.

The feeling of it you can't control, so we're following in his footsteps and doing something that he used to do.

FEILER: Five times each day, in another pillar of the faith, believers pray, reciting verses from the Koran.

The book's 114 chapters recount miracles and stories that are said to have been dictated to Mohammad in a series of revelations that lasted 23 years.

Many of these stories contain prophets from the Hebrew Bible and New Testament-- Moses, David, Jesus.

But Mohammad said his revelation, through Allah, or God, was the final one.

LINDSAY: Who knows when something is going to touch you or not touch you, when you're going to get the closeness to Allah.

Nothing can describe that feeling, but nothing can also tell you when it's going to come, but it came here, so... (speaking Arabic) FEILER: When Mohammad arrived in Medina it was a small farming town.

Today it has a population of over one million.

QURAISHI: We see all these shops.

I understand, it's not supposed to be, you know, pristine like 1,400 years ago.

But it's really hard to stretch my imagination to see what it was like.

That's kind of the experience that we're hoping to have.

It's a completely different community than what the Prophet had.

FEILER: In those early years, the survival of the Muslim community was still in doubt.

BENNISON: Once Mohammad began to receive revelations from God, he very quickly alienated a lot of the pagan Meccans, including his own kinsmen and his own tribe.

Once they're situated in Medina, they started to engage in hostilities with their opponents.

FEILER: Like early Jews against their neighbors or early Christians against theirs, if early Muslims were going to survive they had to fight their stronger enemies.

FENNI: The battle happened between this small hill and there.

FEILER: These are the mountain slopes of Uhud just outside Medina, where Mohammad's followers fought fiercely against the tribes of Mecca.

The Muslim forces were shattered in the battle, Mohammad wounded.

UMAR SALAHUDDIN: Isn't this awesome?

Nabis Assalam and his army were standing right here.

FEILER: Umar Salahuddin is a management consultant who's one of the Boston group.

What an amazing, amazing feeling it is, to be standing right here.

I'm like trembling right now.

BENNISON: The Muslims decide that this was a test sent by God to test their faith by making them taste adversity as well as victory.

And it doesn't destroy the community.

SALAHUDDIN: We take our faith for granted.

The spread of this religion did not come easy.

There was a big price that was paid by a lot of people and we are standing here as a result of that.

It's this feeling that there's something much bigger out there and you are just a very, very small part of it.

I feel like walking barefoot here because maybe the Prophet might have stepped in one of those places, you know.

It's such an amazing feeling.

FEILER: Mohammad recovered, as did his community.

And over the next seven years, his forces conquered Mecca and much of Arabia.

By his death in 632, Islam was the dominant faith in the region.

In the heart of Medina is the world's second holiest mosque.

Called The Prophet's Mosque, it's built around Mohammad's tomb and the site of his Medina home.

A green dome marks the spot where Mohammad's house once stood.

For pilgrims, a visit here is a way to connect to the prophet as a man.

The site is open around the clock to accommodate worshippers.

But for the group from Boston, who've visited several times, coming here also raises challenges.

They're the same ones pilgrims of all faiths encounter, no matter the pilgrimage.

Traveling in congested places, at odd hours of the day and night, with unfamiliar food and little sleep, is taxing.

It tests your body, your mind, even your love of others.

TALHA: My biggest fear is not having enough patience, because that's the general...

I feel media kind of gives people the impression that Muslims are always angry.

And this journey that we will take couldn't be a better test for that.

FEILER: Even at 2:00 a.m., crowds swarm in front of Mohammad's house and the gates that protect his tomb.

TALHA: The space between the place where he gives his sermons and his house is part of paradise on earth, and so everyone tries to get a chance to pray in Paradise.

FEILER: Still struggling with what went wrong in his marriage, Talha begins to feel that coping with these crowds might make him more accepting.

TALHA: If that actually worked, where you could actually carry yourself, you know, patience with you in a suitcase, and just take it out whenever you needed it... My dua throughout the Hajj would be like, "Please, God, don't let me lose it, don't let me lose it."

FEILER: Female pilgrims face an additional challenge.

Their access to the area in front of Mohammad's home is restricted to a few hours each day.

I'm losing track of time.

I have no idea what day, what time it is.

That's true.

QURAISHI: That's all we do, we're going to the mosque, we pray, we go back and then we come back again a few hours later.

We pray, we go back.

It's just that returning over and over again.

FEILER: For American Muslim women, used to being treated more equally, the conduct can be jarring and unnerving.

QURAISHI: It took a lot of concentration.

Women are yelling at you, trying to get you to go.

Telling people to stop their prayer, just keep on moving.

It was really hard for me to concentrate while that was happening.

FEILER: As a Muslim chaplain, Amira finds the separation particularly upsetting because it gets between her and her reason for being here.

I couldn't see anything from the women's section, it was all blocked off.

And it has a direct impact on my feeling as a Muslim.

You know, it feels... (sniffs) Sorry, I don't know, this is weird, this is a weird trip, it's like I get emotional at random moments.

But I was going to say it just feels like the Prophet is farther away.

(laughing): Sorry.

I'm...

Sorry.

FEILER: To go on pilgrimage is to enter a heightened place, where emotions can soar, but sometimes dip.

In the journey, there is risk...

I just want to update everyone about the schedule.

FEILER: ...and readiness.

Tomorrow Anisa and the Boston pilgrims leave for Mecca.

But first they must get into Ihram, a word that represents both a pure state of mind and the simple garments they wear.

LINDSAY: So I'm putting on my Ihram.

What that consists of basically are two pieces of cloth, one for the bottom and then one we wear on top, like this.

It's all cotton, it's all plain.

Whether you're rich, poor, doesn't matter what race, what class.

In front of the eyes of God, you're all the same.

We're not used to wearing clothes like this, and I think that's the whole point, is to come out of our comfort zone, for the sake of God.

FEILER: For female pilgrims, Ihram goes beyond clothing.

MEHDI: Women don't have a uniform like men do, but we'll wear something modest and clean.

We'll take off our makeup, we won't wear nail polish.

We want our external person to reflect the internal person, and we go before God as plain and exposed as we are.

LINDSAY: Now it means we're going to Mecca.

It means the reality of Hajj is on.

So it's exciting and a little frightening.

TALHA: Everyone's going to come to Mecca wearing this white garb, and when we die, we wear this white garb.

So it's a reminder for us that this life isn't infinite, it's finite.

FEILER: The preparation over, the pilgrimage begins.

The journey to Mecca recreates Mohammad's own path as the native son returned to his tribal home months before his death as the leader of a vibrant new religion.

Once there, Mohammad taught his followers the traditions that would become the Hajj.

The trip south from Medina to Mecca has always been rich with symbolism.

When Mohammad did it, it was a sign of triumph, that Mecca had been purged of idols, they were free to worship one God.

At the time it took two weeks by foot.

By camel it would take ten days.

Now there's a highway and it takes three or four hours by car.

But at the height of the Hajj, it can take ten, 12, even 18 hours.

And that only heightens the anticipation.

Now is when the journey truly begins.

(horns honking) IMAM JOHARI: To come into Mecca saying (speaking Arabic) "Here I come, here I come, oh Lord."

All of them coming, day after day, like an army of believers.

Walking into the center of a spiritual universe.

FEILER: Mecca is Islam's holiest city.

The population of two million can double or triple during the pilgrimage.

The heart of the city is the Great Mosque.

Covering almost 100 acres, its multiple levels and corridors are said to hold up to a million pilgrims at one time.

At the center is the Ka'aba, which the Koran says was built by Abraham and Ishmael.

Muslims consider it the House of God on Earth.

On their first night in Mecca, the Boston pilgrims make the ritual known as Tawaf, circling the Ka'aba seven times as instructed by Mohammad.

LINDSAY: When we came here, it was after a six or seven-hour bus drive and we were in our Ihram, so it was tiring.

But when you get your first view of the Ka'aba it's just beautiful.

ANSARI: It was a lot harder than I thought it would be.

These are large circles.

I think it must have taken us two or three hours to walk around the Ka'aba seven times.

You know, we were barefoot, and it's marble floor.

It's slow and you're bumping up against people.

QURAISHI: There are some pinch points where the crowd gets really intense.

If we're just sort of in tune with each other, it's really fine.

But then there's that person who panics because they've lost contact with their partner or something and they kind of try to get through fast or try to push their way through.

ANSARI: During the Tawaf, you're supposed to be praying, you know, like supplicating, and I think if you're really good at it, you're doing that constantly.

But I have to admit, my head wasn't staying in the game.

I was counting the laps, so I ended up engaging Amira in idle chitchat, and she said, "You know, we're not supposed to be chitchatting."

We didn't come here to chitchat.

KHUDAIRI: I didn't know that the mosque was that big from the outside.

That took my breath away.

That really shocked me.

You feel the oneness and how small you are, and that you're just a small part of the whole.

FEILER: Part of the power of Tawaf comes from being surrounded by worshipers from scores of countries, but that carries risks, too.

Tala, like many, wears a mask to protect herself from infection.

KHUDAIRI: Initially, we were on another level.

I tried to stay on the outer edges and safe.

When I saw the Ka'aba, I was drawn that we had to go there.

We belong there.

FEILER: At the southwest corner of the Ka'aba is a black stone encased in silver.

SALAHUDDIN: It is our belief that it's a stone from the heavens and kissing it will put a piece of heaven inside us.

LINDSAY: The hardest is when you want to actually approach the black stone.

Then it gets very tight.

SALAHUDDIN: There's a sea of millions around you and we are all pressed against each other.

I have never felt that much energy go through me.

LINDSAY: I can easily see how you can be crushed to death.

SALAHUDDIN: I was squeezed from all directions.

It was tough to breathe.

LINDSAY: At one point, I was off my feet, I wasn't even touching the ground anymore because there were just so many people.

I just actually went up into the air.

SALAHUDDIN: We took a much longer time to get there because we had decided that we were not going to push, we were going to inch forward.

LINDSAY: With patience, you know, you can get in there without harming anybody.

And I managed to kiss the black stone today, so I was extremely happy with that.

SALAHUDDIN: As I got in front of the stone, I don't know what happened, but the world stopped for a second and there was stillness, and I felt no pushing, no shoving and I was able to go in and kiss the stone.

And then I thought about it for a second.

There was no pressure again so I kissed it again.

I truly was alone with God in a sea of five million people.

FEILER: Anisa and the pilgrims will remain in Mecca for several days before the most important Hajj rituals begin.

Hi, Anisa, how's it going?

How are you doing?

We are exhausted.

There's nobody sleeping here at all.

It's going on midnight and they're planning to gather together at the Ka'aba for the second night in a row at 2:00 and stay all the way through until 6:00 in the morning.

What is the biggest change you are detecting among the pilgrims that you're with?

They are bonding.

They came together, mostly as strangers, and there is that sense also of becoming part of a whole that's greater than yourself.

Let me ask you about this women issue.

Have any of them been startled by the way they've been treated?

MEHDI: I think everybody comes prepared to a certain degree.

What's interesting is that men and women are circling the Ka'aba together.

Men and women, when it's time to stop and pray, are praying next to one another.

However, when you're not in the worship part and people's cultural mores and norms come out, sometimes there are cultural clashes.

FEILER: Beyond contemporary politics, the story behind the Hajj celebrates women.

Abraham, known in the Koran as a "friend of God," is married to Sarah, who can't have a child.

So she offers him her handmaiden, Hagar, who gives birth to Ishmael.

Sarah then gives birth to Isaac.

Now there are two sons.

Tradition says God instructs Abraham to take Hagar and Ishmael to Mecca and leave them in the desert.

Hagar has faith.

"“God will not allow us to be lost,"” she says.

Abraham, back in Palestine, is said to turn and pray toward Mecca.

Hagar, fearing for her son, dashes back and forth between two hills, desperately searching for water.

In the second big act of the Hajj, the pilgrims will recreate that journey, hurrying between two hills.

Hagar and her son are saved when a miraculous spring bubbles up.

Today, pilgrims drink from the purported source of that spring now inside the Great Mosque.

The water is called "zamzam," from the word "stop" Hagar utters to contain it.

QURAISHI: It's so gratifying and exciting to me that one of the main pillars of Islam is literally following in the footsteps of a woman.

She and her son discovered the miracle of the Zamzam water and that is a symbol of God's mercy for us.

FEILER: The Great Mosque contains an enormous covered walkway stretching between two hills linked to Hagar.

Pilgrims reenact the frantic search for water, moving back and forth seven times, for a total of nearly two miles.

QURAISHI: You're feeling the pounding of your feet, you're feeling tired and you're thinking about that moment in time when she was running back and forth.

And as a mother, all you really care about is your child.

So it's a really gratifying part of Islam for me.

We're really walking and it's air conditioned and it's not exactly the same thing.

Not even close, but it's symbolic.

FEILER: In recent years, modernization has transformed Islam's holiest city.

Cranes and bulldozers push back the storied mountains of Mecca to make way for malls, hotels, and one of the tallest buildings in the world.

All to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims, three million or more a year.

They've made the mosque bigger and bigger.

And bigger.

And bigger and bigger.

That allows more people, but some people I hear are frustrated that they're not closer to the Ka'aba.

JOHARI: The Ka'aba has been destroyed by floods and rebuilt over and over again.

There are people who desire to touch it as if they are touching the original stones.

This is not the intent.

It is a house for Allah, but the building itself should not become an object of worship.

FEILER: After the early rituals, there's a break before the pilgrimage gets even more intense.

For pilgrims, it's a reminder that for all their sanctity, sacred journeys are often enormous street fairs, a mass family reunion.

Everybody has been so nice, smiling.

QURAISHI: Definitely a nice break from the norm.

It's nice to just be here.

I think we've been having a good time.

For the most part, we've been able to shut off from our usual life, for the most part.

I haven't completely shut off, like I still check my email.

ANSARI: I'm a little bit of a workaholic, but it's definitely been significant detachment for me, and it's been very nice.

AMIRA: Even though we're, like, all we're doing is sleeping, eating and praying, it feels really busy.

Do they know that it's prayer time?

I didn't hear the adhan.

(man chanting over loudspeaker) FEILER: The call to afternoon prayer rings out across the holy city.

(chanting continues) JOHARI: The injunction of the Koran is to pray five times a day.

People will stop their work.

In Mecca, traffic will stop, shops will close.

(chanting continues) FEILER: The five daily prayers encourage Muslims to break with their routines and surrender to God.

The word "“Muslim"” means "“one who submits to God.

"” LINDSAY: Today after we prayed, I honestly felt that if I died right this second, I don't care.

That's the kind of level I would like to reach and hopefully, inshallah, maintain, but it faded very quickly.

FEILER: Early stages of many pilgrimages feel this way.

The pilgrims glimpse what they're after, but then the glimpse disappears.

There's a reason sacred journeys go on many days.

The seekers must keep seeking.

Soon the Boston pilgrims will get back into Ihram and get back on the road.

And it's like this uniform that everybody wears and so there's no real distinction.

The only thing that makes you distinctive in the eyes of God is what is in your heart.

FEILER: Until now, pilgrims have been traveling alone or in small groups.

But starting today, every pilgrim here for the Hajj will move as one.

It's the eighth day of Dhul-Hijjah, the month of Hajj in the Muslim calendar.

Dressed in Ihram, millions leave Mecca on a route laid out by Mohammad to honor the trials of Abraham.

I always thought the pilgrimage was coming to Mecca, but it's not.

It's actually leaving here and going someplace else.

This is a journey that is following in the footsteps of Abraham and his family, but done in the way of the Prophet Mohammad.

FEILER: 15,000 buses carry pilgrims from Mecca to the Valley of Mina, five miles away.

Worshipers will spend the day in prayer and contemplation before moving on to stand alone before God on the plain of Arafat.

It's a stage familiar to many journeys: the cleansing.

JOHARI: You have now set yourself away from the city, and you stay there for a day.

That day is spent in supplication and prayer and anticipation.

What should I be doing tomorrow when I have those few hours on Arafat?

What should I be thinking about?

How should I be preparing?

FEILER: With Anisa and the pilgrims settled in the encampment at Mina, an opportunity to check in.

Tell me about the accumulated fatigue and how that's affecting everyone on the trip.

MEHDI: These people haven't slept more than two or three hours a night for almost ten days, so their bodies are aching and their feet hurt and they're giving each other back rubs, giving each other whatever medications, and Band-Aids for blisters.

Does it somehow enhance the experience that you're all so tired?

MEHDI: I think it enhances your ability to surmount trial.

FEILER: And there are trials.

For Jack, a black eye he got at the Ka'aba the night before coming to Mina.

LINDSAY: The place was just jam-packed and we were right against the Ka'aba, about five feet from the black stone, and we're making our plan to slowly make our way over.

All I saw was an elbow coming and I had no way to defend myself so just right in the head, I got the elbow.

A little bit later I found that I had this badge of courage.

FEILER: Amira too has an injury that will impact the rest of her journey.

I just twisted my knee in the middle of the night, so I have to finish the Hajj likely in a wheelchair.

If I try to walk on it, it will slow everybody down and I'll be in a lot of pain.

I'm disappointed.

One of the hardest things is really to let people help me.

I don't think I've ever been in this position before.

Everyone's behind you.

QURAISHI: We're supposed to look for signs of God around us, and in us, so every time somebody comes to help me, show compassion for me, that's Allah's presence.

If I am a true believer, I have to show gratitude for that.

Ready to go.

Everybody is here for a spiritual experience, and whatever happens is always welcomed.

We have setbacks, we have hurdles that we have to cross, and it's really our will to cross those bridges and those hurdles.

(chanting) FEILER: After a day and night at Mina, the pilgrims move on to the next stage, traveling nine miles to the Plain of Arafat.

All pilgrims make the same journey on the same day.

The visit to Arafat is the single most important event of the Hajj.

FENNI: Hajj is Arafat.

You cannot have Hajj without being in Arafat.

During that day, the Divine descends to the lower heavens with the angels, because he knows that these, our servants, have come to ask for His forgiveness.

When you know that you've done everything in your power, everything that you know to do to get accepted that day, perhaps you will get accepted.

(chanting) There is nothing on Arafat but desert, and a hope that you might get this acceptance from God for your journey.

FEILER: It was here, perched above the Plain of Arafat on the Mount of Mercy, where Mohammad gave his farewell sermon just months before he died.

The sermon captured the essence of his beliefs.

Mohammad's sermon on the Mount of Mercy contains deep parallels with Moses's farewell sermon on Mount Nebo and Jesus's Sermon on the Mount.

All three contain a call to unity, a plea for compassion and an implicit warning not to lose these values in the future.

But they also have something else in common.

All three take place in the middle of nowhere, as if to say, no one person, no one place, has ownership over these ideas.

They belong to everyone.

There's another tent city at Arafat, created for just this one day each year.

Pilgrims can remain outside or spend the day under cover.

The only focus is on the sincerity of their prayers.

SALAHUDDIN: We are all here individually to connect individually with God, and we each have our own prayers and our own way of connecting, yet we all have a larger common purpose, to connect with God, to pray to God and to be forgiven by God.

I'll be praying for myself, for this world and the hereafter, as well as for my family, my friends, my relatives, colleagues and for mankind.

KHUDAIRI: What I've been learning about during intense times, is that it's not me having to rely on me and my will and my own strength.

But I need to surrender sooner.

FEILER: No matter the pilgrimage, no matter the traveler, the road itself has power.

Often, what it offers is relief.

TALHA: I go through stuff that's happened in my head while I'm making prayers and talking to God about those things.

I hope God gives us a clean slate after this and start all over again.

We'll see where life takes me, I guess.

Am I looking for someone...

If God wants me to find someone, I guess, you know.

FEILER: Strengthened and purified by their day at Arafat, the pilgrims are ready for one of the more colorful events of the Hajj.

They'll spend the night in the Valley of Muzdalifah before reenacting Abraham's dramatic showdown with Satan.

In a barren strip of desert like this, Abraham faces his greatest test.

In a dream, the Koran says, Abraham sees himself sacrificing his son, believing it's a message from God.

The devil tempts him to disobey, the commentators added.

But Abraham defies the devil and declares his loyalty to God.

Judaism and Christianity also commemorate Abraham's willingness to sacrifice a son.

But Islam teaches that Abraham gathers stones and throws them at the devil in defiance.

Pilgrims do the same.

JOHARI: I am now arming myself for the challenge that is coming, that I will meet Satan, and he will tempt me as he tempted our father, Abraham.

FEILER: Here is the immediacy of being on the road.

You don't just read the story, or tell it, or sing it.

You act it.

You become it.

You enter the story, gathering ammunition to throw at whatever it is that's tempting you.

It is a physical embodiment of something that you're constantly struggling with yourself.

When we go back to our homes, leaving this holy place, are we now going to stone, if you will, those urges that really are not abiding by the will of Allah, and that's really what the significance is.

FEILER: At a time when Hajj authorities are believed to bring in tons of stones each year to restock the supply, not everyone disappears into the story.

Fatigue itself is a temptation.

ANSARI: I'm really tired, I'm exhausted, and I'm physically uncomfortable.

This is getting to me, and I really want to shower and put on some normal clothes.

I haven't necessarily been washed over by any tremendous feelings.

It's hard to feel that way.

This is a very industrial and rough environment.

There's no stars, there's no beautiful night sky.

It's not really that peaceful, and others may say it is and that's fine, but I don't feel that way.

It is what it is, you know.

People say I'm cleansed, I did the work, I'll take the certificate.

FEILER: More surprising is that a story that invokes child sacrifice continues to resonate at all.

You would think that this story is so barbaric that it would have died out over time.

What is it about this story?

I don't want anybody to get the idea that this is about a homicide, that God came in and stopped it.

The moral of the story is that God already knew when he asked Abraham that He was going to step in.

TALHA: It was a test.

It was a test of do you trust God more than anything else?

And he was willing to do that, no questions asked.

And, you know, we're just doing this to represent that, that sacrifice.

And sacrifice, without question, is something that in this day and age we don't really get ourselves involved in.

FEILER: With Amira still in her wheelchair, Husam is beginning to see the Hajj through a more open lens.

ANSARI: I don't have this big wow, aha moment of spiritual revelation, so to speak, but I mean the amount of love and support we're feeling from everybody in the group just after Amira injured herself is tremendous.

You know, that affects me.

I get emotional at times like that, because it's at a moment like that that I actually thank God for that person or that moment, so that is my connection.

Or like this gentleman who just helped me collect my stones.

You know, if I wasn't feeling quite so gross, I would have hugged him, you know.

FEILER: It's early morning of the third day since leaving Mecca.

The pilgrims move on to the penultimate stage of the Hajj, returning to Mina carrying their pebbles to stone the devil, which they'll do again and again.

Another vast, multilevel building stands where Abraham is said to have confronted the devil.

At the center of the building, three massive stone pillars-- today they're more like walls-- that symbolize Satan.

JOHARI: It is symbolic, but it's also real, because you are in that place.

You're surrounded by stone.

It's desolate, and that's where God is with you, and the Satan that you can't see, but he's always around, inviting you against your best interests.

FEILER: Once again the pilgrims reenact the past, a reminder that everyone faces temptations every day.

SALAHUDDIN: It's a way to say, "I have control over Satan.

"I can actually push Satan away and I can actually take charge of the situation."

FEILER: The size and shape of the pillars have changed radically over time.

The current structure was built in 2006 to protect pilgrims from being crushed and trampled, as happened frequently in the past.

The evolution of this pillar is quite visually interesting.

So originally, we have a kind of small... Like an obelisk.

Yes, exactly.

Then it evolves and then you've got... it's a little taller, to today where you've got this whole wall.

The importance is not what is the shape of the pillar.

It is "I am in the place of Abraham, and I am doing what Abraham did."

And, by the way, I like the way they changed the structure because the obelisk, if you were on the opposite side and somebody missed a pillar, then you'd get hit with a pebble.

FEILER: Before the current building, the stoning was the most dangerous stage of the Hajj, and stories of pilgrims being killed overshadowed the event.

SAUD KATEB: Lots of people died here.

Even if you are strong, if you are young, once you just fall down, all of this crowd, you'll not be able to stand up again.

Now look-- it's completely different.

FEILER: The Hajj, like many pilgrimages, is a story of layers.

There is the modern world, with its marvels of metal, glass and electronics.

There's the world of Mohammad, with its devotion and rivalries.

There's the world of Abraham, with its family dramas and battles between God and devil.

It's the duty of the pilgrim to navigate these worlds and reach a place that's both new and everlasting.

Today is Eid Al-Adha, the festival of sacrifice, when Muslims worldwide celebrate the saving of Abraham's son, often by sacrificing an animal.

These days, pilgrims pay for a sacrifice to be done in their name, the meat given to the poor.

Pilgrims change out of Ihram, some men shave their heads; and all return to the pillars to complete the stoning.

JOHARI: You perform the pilgrimage to Mecca, you give up your familiar, you give up your lifestyle, your diet, your clothing, lipstick, you give up ththings that are part of you.

Seven pebbles, seven circuits around the Ka'aba, seven days in the week, seven heavens, there's something about that seven, and there's something about repetition for people.

Once it becomes habit forming then, maybe, when you go back, you'll be able to practice.

People get worked up because the fervor, the feeling is there that, "I'm letting some of my baggage go.

"Satan, you broke up my family.

"Satan, you caused me to lose my job.

Satan, my child..." We're in a group therapy, and we're all getting it out.

QURAISHI: The throwing of the rocks, I almost didn't go because I really did not think of it as anything significant, almost even silly.

But I went, and the first one I was throwing rocks as if I was throwing them at my own flaws, and the second one, I found myself asking for strength to overcome those.

And then the last one, I found myself feeling so alive, so happy, that God is stronger than any of those stupid things that we give in to.

So it was really enlivening for me.

FEILER (on Skype): The pilgrims that you're with, if you had to guess, what's the one thing they're taking home?

They're taking home that their life is in God's hands, but still do the best you can.

It doesn't mean sit back and wait.

Sometimes the hurdles along the way are what make the journey valuable.

What do you get by going on a journey like this that you don't get by staying home?

You have to leave home to see what is out there in the world.

And in many of the countries from which these people come, there are wars going on.

And yet here you see people who are working together to generate a community that crosses all kinds of boundaries.

FEILER: That sense of community is certainly on display as the pilgrims return to Mecca, streaming together toward the Great Mosque for the final act, a farewell walk around the house of God.

LINDSAY: You see the condition of so many people and how much more they went through than us.

I'm amazed at how strong they are, and you know I'm amazed at how so many ople came together.

I've never seen anything like that.

You would think with that many people, there'd be serious problems with the lack of amenities and food at the end, water, resources, it would be a lot harder.

But people got through it all.

It's amazing.

SALAHUDDIN: To me, the Hajj will start when we land at JFK.

That's when the real Hajj will start, right?

Because that is what you are taking back.

JOHARI: Many people come back with a kind of freedom.

If you can imagine having weights on your hand and you're learning how to box.

And then they say, "Okay, now it's time to put the gloves on and take the weights off," and then you fly like a butterfly.

There's another step in your stride.

TALHA: I think I've moved on, maybe.

But it's still too early to call.

I inquired about someone yesterday.

It didn't work out, but I took that first step and I was like, maybe I am ready to move on, you know.

Maybe I have found the peace in myself to leave the past behind as is.

ANSARI: I didn't like the fact that Amira got injured.

There was a lot of pain and frustration, but we did see some amazg blessings out of it too.

I do feel more connected with God and my Creator and I feel more resolved to be more observant in my practice.

FEILER: The journey ends where it began, with a simple walk, seven circles.

Only now, few look backwards.

Instead they look forward.

QURAISHI: I feel so happy.

This is so great, so great.

You know, if we just tap into that source, the loving, the kind, the generous God, we as humanity can overcome all of the horrible things that we do.

JOHARI: Allah created human beings in the best mold, and when you see them on Hajj, they are, with all of their difficulties, on their best human behavior.

If human beings, year after year, decade after decade, millennia after millennia, can do that, then it means there is hope for humanity.

FEILER: And perhaps that hope is the true destination of the Hajj, along with the realization that it can only be achieved with the cooperation of others.

It's the ultimate lesson of the sacred journey.

The road is tough.

You can't survive alone.

The only way to get through is to open yourself up to the suffering and the support of those around you and maybe that's the point all along.

FEILER: I'm at the Ganges River at the largest gathering of humanity on the planet.

Every 12 years, tens of millions of people gather over 50 days to bathe in these waters.

This year, among the hundred million expected at Kumbh Mela are American pilgrims on a journey of discovery.

Can they draw closer to their god?

WOMAN: My aim is to understand God.

FEILER: The Kumbh Mela, next time on Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler.

Find more information and exclusive video on Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler at pbs.org/sacredjourneys.

Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler is available on Blu-Ray and DVD.

To order, visit shoppbs.org or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

The Birthplace of Islam (The Hajj)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep4 | 5m 25s | Video resource from PBS LearningMedia. (5m 25s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Ep4 | 1m 35s | Travel with American pilgrims to the Hajj. (1m 35s)

Notes from the Field: Anisa's Story (The Hajj)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep4 | 3m 19s | Meet journalist and filmmaker Anisa Mehdi. (3m 19s)

Notes from the Field: Citizen Journalists (The Hajj)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep4 | 2m 45s | Technology and social media at the Hajj. (2m 45s)

Circling the House of God on Earth (The Hajj)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep4 | 5m 30s | Video resource from PBS LearningMedia. (5m 30s)

Notes from the Field: Jack's Story (The Hajj)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep4 | 3m 12s | Meet American pilgrim Jack making the Hajj. (3m 12s)

Notes from the Field: Modern Mecca (The Hajj)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep4 | 2m 11s | In recent years, modernization has transformed Islam's holiest city. (2m 11s)

Notes from the Field: Shopping in Mecca (The Hajj)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep4 | 3m 17s | Go shopping with American pilgrims Amira and Husam making the Hajj. (3m 17s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.