Jerusalem

Episode 3 | 54m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

Premieres Tuesday, December 23, 8/7c.

The Hebrew Bible instructs all Jews to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year. But the city is holy to more than just Jews: Christian pilgrims began coming to Jerusalem and the Holy Land within centuries of Jesus' death, and the Al Aksa Mosque, located inside the walls of the Old City, is considered the third holiest site in Islam after Mecca and Medina.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.

Jerusalem

Episode 3 | 54m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

The Hebrew Bible instructs all Jews to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year. But the city is holy to more than just Jews: Christian pilgrims began coming to Jerusalem and the Holy Land within centuries of Jesus' death, and the Al Aksa Mosque, located inside the walls of the Old City, is considered the third holiest site in Islam after Mecca and Medina.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Sacred Journeys

Sacred Journeys is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

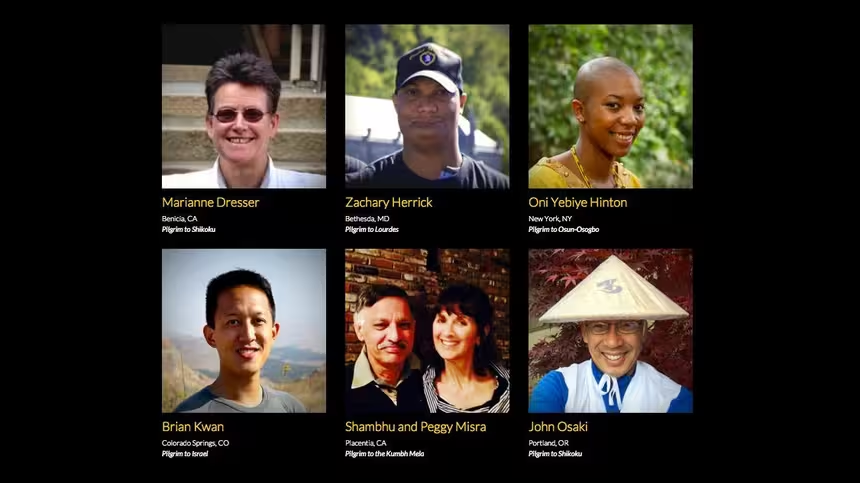

Meet the Pilgrims

Meet pilgrims from the Hajj, Shikoku, Jerusalem, Lourdes, Kumbh Mela, and Osun-Osogbo pilgrimages.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipOh, my God.

BRIAN FEILER: It's the most contentious land on earth, drawing believers from around the world.

Jews, Christians and Muslims visiting sites of faith and conflict.

Despite all the rivalries and entanglements, in the end, everybody is worshipping the same God.

But for the pilgrims I meet in this holy land, the questions are more personal.

How do you thank God?

MAN: We're looking for a faith experience, a spiritual experience.

FEILER: Can a journey to the roots of their faith save them in a time of crisis?

MAN: I lost hope.

The only thing that I had left was knowing that God was with me.

(gong rings) FEILER: Today, organized religion is more threatened than ever, yet pilgrimage is more popular than ever.

I'm Bruce Feiler.

In this epic series, I travel with American pilgrims on six historic pilgrimages.

I bathe in the rivers of India, dance in the heart of Africa, cleanse in the waters of Lourdes, trek through the temples of Japan and walk in the footsteps of prophets in Mecca and Jerusalem.

I attend some of the most spectacular and moving human gatherings on earth.

And I ask, what can these journeys tell us about the future of faith?

FEILER: It's been called the birthplace of humanity.

Jerusalem: holy to Jews, Christians and Muslims, half the world's believers.

This city has been built, sacked, rebuilt and wept over dozens of times in the last 3,000 years.

(chanting) The Western Wall is the all that remains of the Jewish Temple compound that was destroyed almost 2,000 years a.

(cnting) It's the holiest spot in Judaism.

Jews from around the world gather here every fall for the harvest festival of Sukkot, the Feast of the Tabernacles.

RABBI DAVID ROSEN: Jewish tradition suggests that there's a kind of unique shaft of holiness that connects this earthly Jerusalem as the most holy place in the universe directly to the footstool of heaven.

So Jerusalem becomes therefore the focus of the life of the people, the focus of their pilgrimage.

FEILER: The Hebrew Bible says all descendants of Israel should make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to see the Temple three times a year: in the spring for Passover; in the summer for Shavuot, the holiday that marks the giving of the Torah at Sinai; and in fall for Sukkot.

After the destruction of the Temple, pirimage began to lessen in importance in Jewish life.

It never disappeared entirely, but when Jews spread all over the world-- many in ghettoes-- coming to Jerusalem wasn't really an option.

Now it is again.

I love coming here, because it's a place where religion infuses the air and lives in the stones.

Since the Temple was destroyed, Jerusalem has been conquered again and again in an endless tug-of-war among Christians, Muslims and Jews.

Each has its own unique claim to the place.

Christian pilgrims began flocking to this city within a few hundred years of the death of Jesus in the 1st century CE.

(chanting) RABBI ROSEN: And because of course Christianity is uniquely focused around issues that related to pilgrimage, the whole of the Christian world comes focused on Jerusalem.

And then, because of Jerusalem's significance, when Islam comes along, it affirms that it is not only the continuity, but actually the confirmation of all that is true and noble that's gone before and therefore it seeks to affirm its stake with regards to Jerusalem.

So you have this incredible focus of history, of geography of the different traditions and cultures on this rather tiny little location.

FEILER: Throughout history, pilgrims from all three religions have come to Jerusalem seeking something deeper within themselves, some connection with the Divine.

But for Christians especially, Jerusalem is not the only place they visit while on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

While Jesus ended his days in Jerusalem, a number of the key events in his life occurred several hours north of here, in the Galilee.

Many Christian pilgrims begin there.

Nazareth is the childhood home of Jesus.

Adam and Christina Bourne are young Americans about to set out from a 200-year-old guesthouse on a four-day, 40-mile hike to the Sea of Galilee to visit places where Jesus taught.

It's called the Jesus Trail, created in 2007 as a common thread linking different cultures and different faiths in modern Galilee.

20% of all citizens in Israel are Arabs, 80% are Jewish.

In the Galilee it's 50/50, and Nazareth is 100% Arab.

The Jesus Trail is like a mirror of history.

CHRISTINA: So would the road have started here?

ADAM: Well, let's look.

It's been over 2,000 years.

FEILER: This is Adam and Christina's first visit to the Holy Land.

They've been married several years and are considering starting a family.

Like many pilgrims, they're at a time of transition in their lives.

Jesus walked through here.

He had to have used this road, right?

Mm-hmm.

ADAM: Walking on history.

CHRISTINA: It brings the stories to life for sure, and then to be able to go back home, and every time you read it, then you've got the mental picture of... ADAM: I've walked this road, I've walked this path.

This being the only road at the time, there were other people that were traveling this road.

And you think of all the different folks that he met along the way.

You know, just brushing shoulders with folk that maybe didn't know who he was.

And then they get down the road and they find out later, that guy performed a miracle in Cana not three days ago.

And it all happened right here.

FEILER: The idea of walking to get closer to God is a theme that links Christianity with its Jewish roots.

The theme goes back to the core story of the Hebrew Bible, the Exodus, when the Israelites leave Egypt and wander for 40 years in the desert.

I'm heading to the desert with my friend Avner Goren, the legendary Israeli archaeologist, who's been my guide on previous trips.

He takes me into the Negev, a vast, sparsely populated desert that makes up more than half of Israel today.

This area is home to many of Israel's Bedouin, who've been here for thousands of years.

Abdullah is a friend of Avner's who welcomes us with Bedouin hospitality.

We're out here in the open desert.

One of the most common phrases in the Hebrew Bible is "Remember you were once strangers in a land with no hope."

It's almost as if the Bible seems to be saying, "Your tendency is going to forget "what happened in the past, "but we want you to remember that wandering was part of your past too."

Very much so.

A key idea of the holiday of Sukkot is to reconnect wi that wandering faith.

FEILER: Once the Israelites entered the Promised Land, they dispersed.

It took King David, 1,000 years before Jesus, to create a unified capital in Jerusalem.

RABBI ROSEN: From a historical point of view, it was David who gave Jerusalem the special significance because he realized that he needed a central focus around which he could unite the disparate tribes of Israel.

And if you want to have a real unity of purpose amongst the people, it's not just to have... enough to have a political location; there has to be some spiritual vision behind it, where the Ark of the Covenant was to be housed, where the Temple was to be created around it.

FEILER: The Ark of the Covenant was the tabernacle the Israelites used to carry the Ten Commandments through the desert.

It contained the word of God, but it had no permanent home.

After David conquered Jerusalem in the tenth century BCE, his son, Solomon, built a permanent headquarters for God on a hill that had long been holy to pagans.

This was the Temple, and Jews from across the region made pilgrimages here three times a year.

RABBI ROSEN: The occasions are associated with both historical events, but also with the seasons.

Passover is a spring festival, Pentecost is the beginning of the first fruits, Tabernacles is the end of the agricultural season.

FEILER: During Sukkot, temporary shelters made of wood, cloth, palm fronds-- and nowadays steel-- pop up all over the city.

They are reminders of a time when the Israelites were wandering with no settled home.

So you walk around the city like this and you just see them everywhere.

Okay, so this is one here.

People eat in here, right.

FEILER: Ahava Zarembski is an American Jew who, like me, has spent a lot of time in Jerusalem.

But this week, she hopes to make a critical decision: whether to stay in America or move to Israel on permanent pilgrimage.

Now you have a foot in both worlds, what are you hoping to find during this stay?

I made this trip because I was tired of feeling alone in my Judaism.

And after celebrating a full year of holidays in the States, I said, never again will I celebrate the holidays in the States.

I'm deeply rooted in my faith, I'm deeply rooted in my tradition, and so the concept of holiday here is completely immersing, where I feel a part of something much bigger than myself.

FEILER: Because Sukkot celebrates the harvest, plants are key.

Ahava visits her local market to buy the holiday symbols.

ZAREMBSKI: The etrog, which is this beautiful-smelling fruit.

It's kind of the family of a lemon, and it represents the heart of a human being.

The etrog is supposed to be perfect and completely beautiful.

FEILER: Finding the perfect etrog is a national obsession, as is finding a perfectly straight lulav, the unopened frond from the date palm that symbolizes the human spine.

Along with myrtle and willow boughs, these four species represent the best parts of being human.

Bring it together and then I'm going to go to the right.

To the right.

Then to the left.

To the left.

Straight ahead.

The heart, right.

And then up... FEILER: Shaking this sacred bundle acknowledges that God fills the space that surrounds us.

Branches from these four species are often used to build the sukkah, the temporary shelter where people dine during the festival.

ZAREMBSKI: And so for seven days in Israel, you leave your house and you go into a temporary dwelling that you built.

I'm a female, I'm a Jew, I'm an artist.

I love the idea of celebrating my Judaism in a physical way.

FEILER: The act of leaving your house and entering a sometimes shaky structure is like going on a pilgrimage within your own daily life.

RABBI ROSEN: We dwell in the booths today to remember Divine Providence, to remember and to instill in ourselves an awareness that real security and real stability do not come from material things.

FEILER : Ahava built her own sukkah in the parking lot of the apartment where she's staying.

Well, you did it, it's standing.

I did it, yes, with the help of others.

FEILER: What was the hardest part?

AHAVA: So about an hour before the holiday came in, the winds came and blew the entire thing down.

I'm not kidding you.

So part of the whole week is, let's go dwell in our sukkah, but let's hope it doesn't fall down.

I think part of the fallacy that we live in, the obsession over materialism is part to do with control, but what's control?

It's about wanting to be safe, and wanting to be secure.

But at the end of the day, what's really real is the fact that nothing is permanent.

FEILER: All pilgrimage is built on this notion of dislocation, of leaving what's comfortable to seek answers that may make you uncomfortable.

For Ahava, the question is, where should she live her faith?

For Adam and Christina the question is, can they make their faith more real?

For American Brian Kwan, also walking the Jesus Trail, the question is, can he overcome a crisis of faith?

Three months and four days ago, my dad suddenly passed away.

I just never really thought about my dad going away like that.

In fact, I've never thought about my dad going away at all.

I just arrived in Israel two days ago.

Right now I'm in Nazareth, and the very first stop is this church over here where Jesus turned water into wine.

And this was where people really started to question whether or not he was the Messiah.

FEILER: Brian's parents were Buddhists from Taiwan, but gave him no formal religious training.

KWAN: I always wondered if I was blindsided by a car, where would I go?

It was just so mind-boggling to me to think about, and it would actually keep me up at night because I had no background in faith.

When I turned 16 I decided to go to my first church service, and that's where I experienced God's love and his story.

God the father loves his son so much and yet he gave up his son so that we may live.

That story about a father and a son relationship is so intriguing to me, that is actually what brought me to Christ.

FEILER: A related question has brought him here.

Over the years, Brian has heard that only Christians go to heaven, but since his father wasn't Christian, what does that mean for him?

So it shook my faith quite a bit and I decided to make this journey of mine so that I could reexamine my life and determine whether or not Christianity was going to be the faith that I was going to pursue for the rest of my life.

What does it mean to question whether you want to be Christian?

Questioning is very important for my faith because I think the moment that you stop questioning, that's the same moment that you kind of stop growing in your faith.

You're either always walking towards the direction of God or you're walking away.

FEILER: The Galilee is a landscape of faith, but also struggle.

It's filled with biblical sites, early churches and the ruins of ancient synagogues.

The Gospels say Jesus performed a miracle on this spot.

For Brian, the place raises the question of wther his father received God's blessing.

KWAN: If there is really a creator, then my dad probably would have met his creator.

My question isn't so much, was my Dad a Christian?

My question now becomes, is Jesus Christ the Messiah?

Because if he is, then I believe whole-heartedly that my Dad is in heaven with him.

That's another reason why I decided to embark on this journey.

FEILER: The climactic event in Jesus' life occurred in Jerusalem.

The southern steps are one of the best preserved remnants of the Second Temple compound that was here 2,000 years ago when Jesus lived.

This structure replaced Solomon's temple that was destroyed 600 years earlier.

I always like this spot personally, because to me it feels like what it must have felt like 2,000 years ago.

You're an archaeologist.

When Jesus came here, we know that he was walking up and down these steps?

RABBI ROSEN: Every Jewish person, every member of the different tribes of the people of Israel, aspired to come up to the Temple for the pilgrim festivals.

By that time, the Second Temple period, Jerusalem's place is categorically confirmed as the center, as the pilgrimage location, as the unique place of God's dwelling in this earthly world.

FEILER: Within a generation of Jesus' death, Jerusalem was burned again-- this te by the Romans-- and the Second Temple was destroyed.

Thousands of Jews were slaughtered.

Others fled into exile.

These are massive cut stones; where are they from?

RABBI ROSEN: For many Jews, they thought it was the end of the whole story, especially those cast off into exile.

The idea of Jerusalem, the idea of pilgrimage, of being able to visit, was a dream, was a hope that was passed on from one generation to another.

We are privileged to live in the time when we can actually not only live in, but flourish in Jerusalem.

This was something which generations before could never imagine.

(chanting) FEILER: The Western Wall, known for centuries as the Wailing Wall, is considered the holiest spot in the world for Jews because it would have been closest to the Temple that once stood here.

Among the thousands here today for Sukkot are Lazer and Leibel Mangel, cousins from Ohio.

A lot of people say that spirituality is for the old, that young people, they're caught up in tir digital technology and they don't care about something as abstract and untouchable as God.

LAZER MANGEL: And I'll tell you, I was the same way.

I think eventually you find yourself living a kind of empty life, and you find yourself looking for something greater, something to ground yourself, something to kind of anchor yourself to.

Here we're all the same.

We come here for... FEILER: Seven months ago, Liebel came here to join the Israeli Defense Forces and turn his faith into service.

Coming here for this experience, getting to serve my people, getting to protect my land is once in a lifetime.

So you are going to walk down here, put your hand up on that wall; what are you going to feel?

LEIBEL: I think every time it's different.

You just thank God for everything you have.

It's really not a thing you can put into words.

FEILER: But it is something you can feel.

At least if you come, at least if you open yourself up to the possibility.

Jerusalem is not just holy to Jews and Christians, it's holy to Muslims, too.

The city was the first one Muslims prayed to in the early years of Islam and Mohammad is said to have come here during a miraculous nighttime journey.

Today, Arabs make up 80% of the Old City and half the modern city outside the 16th century walls.

Jamal Amro and his family live in East Jerusalem, right below the Al-Aqsa mosque, which is built near the spot where it's believed the Temple once stood.

JAMAL AMRO: It means a lot to be Muslim in Jerusalem because you are living in one of the most important cities in the world.

Every Muslim is recommended to come with his family to Al-Aqsa Mosque.

In spite of 200 mosques in Jerusalem, Al-Aqsa Mosque has extra value.

Millions of Muslims in the world, they are dreaming to pray in Al-Aqsa Mosque.

FEILER: For more than 1,000 years, this has been one of the most sacred sites in all of Islam.

(chanting) Let's look out at this landscape for a second.

Here's the Mount of Olives.

We see churches commemorating where Jesus was the night before he died.

You've got the Western Wall, Jewish tradition that this is where Abraham went to sacrifice Isaac and where the Holy of Holies was.

You've got the Dome of the Rock, you've got Al-Aqsa.

Is this a city of conflict or a city of coexistence?

Both.

Right now, at this moment, we are sharing the city, but it's almost like a couple in a bad marriage.

They continue to sharing the same house, they rub shoulders in the kitchen, but you have this little bit of unease.

Who'd provide the marriage counseling here for this troubled city?

I would say that there's a lot to share.

FEILER: The central Petri dish in that troubled marriage is the Old City, the most contentious third of a square mile in world religion.

It's divided into four quarters: Jewish, Muslim, Christian and Armenian.

Beyond those interfaith divisions, there are even greater intra-religious rivalries, as different denominations fight with one another over who controls access to the sacred sites.

RABBI ROSEN: Generally speaking, this city, which should be an inspiration to the three religions to have a special respect and bond with each other has been more fought over than celebrated, and there's been more competition than partnership.

FEILER: It's quite dramatic.

You can get a sense of the tension and also the heightened emotion in this place.

You can see there, that's the top of Al-Aqsa.

And this pathway, which is a way for Muslim worshippers to climb up to the top of the dome, when it was opened, it created a clash a number of years ago.

What always strikes me about coming here is the layers of contention.

Not only do Jews and Muslims fight over this space, but Jews are fighting other Jews over access to the Wall.

As romantic as pilgrimages can be, there's a risk that contemporary politics can overwhelm the journey.

To me, to be a pilgrim is to push through that layer of now, to reenter the past and maybe for the first time ever make contact with the foundation of who you are.

The Koran says that God is the God of all of us.

This God is the God of Abraham, he's the God of Moses, he's the God of Jesus, he's the God of the Prophet Muhammad, and ultimately it's the same God.

When Muslims come to Jerusalem, definitely they are fulfilling almost like a commandment.

The Prophet said that Muslims can travel to either of the three mosques, the mosque in Mecca, the mosque in Medina or the mosque in Jerusalem for spiritual pilgrimage.

FEILER: Muslims have been making pilgrimage to Jerusalem since the time of Mohammad in the sixth century.

Christian pilgrimage began earlier, becoming popular after Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity in the fourth century and made travel safe.

It was Constantine's mother, Empress Helena, who made the most important pilgrimage.

Traveling just a decade after her son's conversion, she ordered the construction of a string of churches, from Nazareth to Bethlehem to Jerusalem.

When Empress Helena came here, local Christians told her of the tradition that this is the place where Jesus was crucified, buried and resurrected.

On the orders of her son, a church was built.

Ever since, for pilgrims to the Holy Land, a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre has been a highlight of their journey.

FATHER GARRET EDMUNDS: If you accept the fact that these events happened here-- the story of Jesus' life, the central events of salvation as Christians understand it-- we can argue that it is the most sacred place in the Christian world.

(bells tolling) This is a building that's shared between six different Christian traditions, different cultures, different experiences and expressions of their religious faith.

And they all want to be able to get as much out of this building as they can.

For the most part, it works out pretty well.

FEILER: Here's an example of how intense this rivalry has been.

A century ago, a dispute arose over this step.

The Greek Orthodox control the plaza, and the Franciscans the stairs.

So which is this?

Is it a stair, or is it part of the flat surface?

At one point, that dispute became so heated the two sides descended into violence.

With different Christian groups controlling different parts of the building, almost 1,000 years ago, a solution was devised for a specific problem.

Who controlled access to the front doors?

Every day before dawn, Adeeb Joudeh makes the same walk.

Since 1192, his family and one other have been assigned to keep the key to this contentious church.

(knocking on door) The Muslim sultan who ruled Jerusalem in the 12th century was so fed up with the constant bickering among Christian factions, he appointed two Muslim families to guard the door.

Today, Christian monks still lock themselves inside overnight to protect their territory, only to be let out in the morning when the Muslim overseer arrives.

It's a reminder that for all the tension, these different faiths still share an interest in maintaining the sanctity of these holy places.

(knocking) Only when Christians and Muslims in this Jewish state cooperate can the great doors be opened and the flocks of pilgrims and tourists who've gathered outside enter the place where a Jewish teacher was crucified by pagans 2,000 years ago.

As hard as you try, you cannot separate one of these religions from the other, especially here.

To come on pilgrimage to this land is to be reminded of the permanent braid that entwines the children of Jerusalem.

Adeeb Joudeh tugs on that thread every day-- a peacemaker in a place of turmoil.

Is this the original key?

This is the original.

Is there a back-up?

What happens if you lose it?

I have also another one in my house.

Oh, you do have another one.

Now, can I see... you have a document here.

May I see what you've brought me?

Okay, so can you tell me what it says?

(speaking Arabic) So this is the stamp of the Sultan that indicates that it comes from his private stationery?

Your family name is right here?

Yes.

FEILER: An 800-year-old charter written in liquid gold, giving a Muslim family in a Jewish country control over Christianity's highest church.

A shared land, indeed.

(bells ringing) It's the richness of this land and the depth of that tradition that pulls me back here over and over again.

From the first moment I came to Jerusalem, I felt at home.

I always thought of myself as a bungee cord.

I would travel to a new place and bounce back.

But when I came here, I wanted to stay.

I've come to realize over the years that almost everyone who comes to Jerusalem feels the same way.

A visit to Jerusalem is an invitation to find out more about who you are and especially what you believe.

We're now halfway through the week of Sukkot.

Ahava invites me to visit friends in their sukkah.

Channa Mason and her husband, David, are Americans who've made the decision to live in Jerusalem full time.

It's the choice Ahava faces for herself.

ZAREMBSKI: My grandparents from my father's side are Holocaust survivors.

(praying) ZAREMBSKI: What that means in terms of Jewish identity is so complex.

Our relationship with Israel and the need for Israel to survive was a matter of personal survival and of national survival and that was infused in our blood.

Do you feel like you are on a permanent pilgrimage?

Yes, but I'm not exactly Israeli.

I'm always going to be an immigrant.

I'm always going to be, to a certain degree, a foreigner.

DAVID: I absolutely found myself at home here in Israel, but it's constantly a process.

So much of what our Jewish tradition is trying to tell us is that we're put here on earth to be growing and to be exploring.

ZAREMBSKI: As a Jew in America, I really have to search out my Judaism and I have to go to the places where, you know, the community is.

And here it surrounds me.

FEILER: What's unique about the land of Israel is that the same sliver of earth-- 70 miles at its widest-- nourishes pilgrims with such different beliefs.

But that land is also rugged, arid and harsh, especially for pilgrims.

Brian learned this firsthand.

KWAN: I was going to take a hike to Kibbutz Lavi.

It's only supposed to be about a four- to five-hour hike and I had a liter and a half of water, which I thought was going to be enough, which ended up being one of the first bad decisions of the day.

So carrying five liters of water is mandatory.

KWAN: I continued on the journey and I saw a town and I thought that that was going to be my next destination, but it turns out it wasn't, it was another town.

And that's when I figured out that I was supposed to take an exit somewhere.

The Jesus Trail markers had stopped; that's when I realized just how unshaded and how hot it was.

There'd be bushes and bushes of thorns, I mean just fields of thorn.

By now I'd run out of water, I'd opped sweating, and I knew that that was one of the signs of dehydration.

That was the scariest part.

But I knew that God was with me and that my Dad was with me too.

And I could imagine my Dad seeing me in that condition and being really sad for me.

(voice trembling): I would never want to do that to my Dad so... FEILER: Two hours pass before Brian sees a group of hikers who can help.

KWAN: And I asked them in English, "Do you guys have any water?"

And they said, "Yeah, yeah, of course," and so they invited me to go under the tree with them and they were so kind.

I ended up hiking for ten hours.

I don't know how I'm still alive or conscious.

FEILER: The scare has been a transforming moment for Brian.

As he reaches the great cliffs that look down on the River Jordan and Sea of Galilee, he's ready to make the decision about the future of his faith.

Oh, my God.

KWAN: I just feel like I've literally conquered a mountain.

I went down and up a mountain.

FEILER: Jesus' story is particularly conducive to pilgrimage.

Many of the key events in his life took place in natural settings-- on the top of a mountain, by the side of the road, here on the Sea of Galilee.

For pilgrims seeking a reflective experience, the Jesus Trail is ideal.

It takes you out into open places where you can have a private encounter with God.

Adam and Christina have reached a similar juncture.

ADAM: We're looking for a faith experience, our spiritual experience while we're here.

CHRISTINA: I think the pilgrimage, the idea of it was me connecting with God, but I think He's telling me that He's there all the time, whether I'm in the Holy Land or not.

I had a very set expectation that I was going to have these feelings, these thoughts, these emotions, this spirituality just flood me.

And at first I was a little disappointed when I didn't get that.

There's something special about this place for sure.

But I'll look back and say, things that happened weren't even on my radar of what to look forward to.

FEILER: They've arrived at the Mount of Beatitudes, where tradition says that Jesus gave his plea to compassion, the Sermon on the Mount.

FATHER EDMUNDS: What I want to encourage people to do on a pilgrimage is to look at these stories anew, fresh.

They're so familiar to us, they can become mundane because of their familiarity.

"Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

"Blessed are the meek, "for they will inherit the earth.

"Blessed are those who hunger and thirst "for righteousness, for they will be filled.

"Blessed are the peacemakers, "for they will be called children of God.

"Blessed are those who are persecuted "because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom in Heaven."

ADAM: 2,000 years later, here we sit, but it's the same words, it's the same place.

CHRISTINA: We focus so much on how divine he was, which is huge, but he was also a man, which is just as huge.

The whole point was that God sent someone to be here with us and to understand what we've been through.

This is the first time that I've really been able to connect with that and understand who he was as a man, more so than I ever have been able to before because of the pilgrimage.

FATHER EDMUNDS: Probably a majority of the gospel stories we have about Jesus took place in this little corner of the Sea of Galilee.

It was on the Sea of Galilee when he first encountered these fishermen and called them to be his disciples.

FEILER: For more than 750 years, Franciscan friars like Father Garrett Edmunds have protected the Christian shrines and welcomed pilgrims to the Holy Land.

FATHER EDMUNDS: Often times, even today on the Sea of Galilee, in the late afternoon, a storm comes up and the sea, which is normally smooth as glass becomes very choppy and very difficult and very threatening.

And the disciples were afraid that the boat was going to sink.

ADAM: "He replied, ye of little faith, "why are you so afraid?

"And he got up and rebuked the winds and the waves and it was completely calm."

FEILER: Adam and Christina have reached the place many pilgrims reach, no matter the religion.

Where a faith that may have been abstract or assumed becomes grounded to history and landscape.

Back in Jerusalem, the landscape comes alive on one of the final days of Sukkot.

Today is the mass blessing of the Jewish people that occurs at the climax of the pilgrimages in the spring and fall.

It's 7:30 in the morning and I'm standing in the male section of the Western Wall.

People have been gathered for hours now, assembled close to the wall to get a good place.

You see lots of people now streaming in, carrying their lulav and their etrog, chanting is picking up.

You get the sense that something exciting is about to happen.

Tell me what's going on here.

There's a blessing of the priests to the people, which is a commandment all the way back to the time in the desert, Bruce.

And we've been doing it since.

That's Jewish tradition.

Hundreds of priests will come and at one time give a blessing to the people of Israel like it used to be at the Temple.

(chanting) FEILER: Around 80,000 people gather for this special occasion, though only men descended from Moses' brother Aaron are included in the ritual.

They're called Kohanim.

We just finished the morning prayer and we're coming up to the priestly blessing.

So all the Kohanim are removing their shoes as if they were on the Temple Mount.

(chanting) (worshippers chanting in response) FEILER: Mass blessings like these took place daily when the Temple stood, but were stopped during the years of exile.

They were reinstated after Israel captured the Old City in 1967.

These worshippers are not taking pictures, they're using cell phones to transmit the blessing live to Kohanim around the world.

RABBI SELAVAN: There's this moment of a sense of God's presence and of blessing and of hope.

Something is happening amidst all the confusion-- who are the Jewish people, who are the people of Israel, all the politics.

This is a moment that, as it says in the Bible, as it's in tradition, as we did for hundreds of years in the Temple, we have a taste of what that was like.

FEILER: The threads of faith continue to unfurl and to tug believers of all faiths back to this land.

Adam and Christina have now arrived just outside the eastern walls of the Old City at the Mount of Olives.

FATHER EDMUNDS: The Garden of Gethsemane is the place where the story of Jesus' passion and suffering begins.

Jesus, even in his humanity, has a sense that great events are about ready to unfold.

And he's not sure in his humanity if this is really something that he's ready for and up to.

ADAM: You seem really sad.

I have a lot of... yes!

But it's a peaceful place.

It wasn't.

I mean did you read on?

Yes, this is where he was apprehended.

FEILER: Gethsemane is the place Jesus' impending death becomes real for many pilgrims.

But it was God's will.

FATHER EDMUNDS: He accepts what lies ahead and that's why it's important for us as Christians to remember this is something that in a human dimension is very real.

FEILER: This last stage can be a deeply emotional experience as the pilgrims feel as if they are walking in the footsteps of Jesus' final days.

Just as Jesus walked, they walk and as in all sacred journeys, time seems to collapse and the pilgrims feel as if they are entering the past.

FATHER EDMUNDS: The events from his arrest, to his condemnation, to his carrying of the cross, to his arriving at Calvary and being nailed to the cross, to his being lifted high on the cross, to his dying on the cross are all part of what in the Christian tradition is known as the Way of the Cross or the Via Dolorosa, the Way of Sadness.

FEILER: Early Christian pilgrims mapped out these steps along a route that became known as the 14 stations of the cross.

ADAM: A lot of people witnessing this.

CHRISTINA: It's not like it was an untrodden path that he was taking.

ADAM: Yeah, by design they wanted him to come through the busier part of the city, so that he could essentially be on full display.

Okay, here's five then.

FEILER: This is station number five, commemorating where a bystander was told to carry Jesus' cross.

If pilgrimage is about difficult questions, this may be the most difficult: Why did Jesus die?

Christina and Adam are now where tradition says that crucifixion occurred: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

FATHER EDMUNDS: Part of the Christian narrative is that the conflict, the pain, the difficulty that we experience in this world is not something that I think human beings have oftentimes found that they can solve all on their own.

And so we come to this place and we remember that by rising, Jesus calls us to share in that risen life, which transcends the conflicts and the hurts and the pains of this world.

CHRISTINA: This isn't a museum, this was built around a site that was real, and things that happened that were absolutely real.

There was a man named Jesus on a cross and he died and was buried, and was washed on that stone.

Those things are all very real.

FEILER: But what happened next?

For pilgrims, that is the very real question that being here raises: Was Jesus resurrected?

Was he saved by God?

And will I be?

FATHER EDMUNDS: Pilgrimage can help us to frame the reality that we experience.

It doesn't mean of course that those things all go away, that you no longer have any problems in your life, but you're able to look at those problems from a different perspective.

CHRISTINA: I guess I came here thinking I would be sad, but instead I'm happy because He's not here, and that's a good thing because He still lives on with us today.

FEILER: Pilgrimage doesn't always provide the answers, but it often provides clarity.

Brian has reached his destination.

He's arrived at the River Jordan, where the Bible says Jesus was baptized.

And for Brian, the mourning son, he's come to realize that his spiritual crisis was mostly grief over his father's death.

He's now ready to rededicate himself to his faith.

KWAN: An American group is coming.

They're bringing their pastor, and so my hope is that I'm going to be able to get baptized alongside them.

WOMAN: Hallelujah!

(cheers and applause) KWAN: And that's going to be kind of the symbolism of my old life going away and being washed away.

And then I'm going to be lifted up, proclaiming that I believe in the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

WOMAN: Hallelujah!

(cheers and applause) KWAN: When I began this journey, I think I was seeking assurance-- assurance of where my dad is right now, assurance that I'll see him again.

I can't say that I'm disappointed that I didn't find that assurance.

I think there's a part in just letting time heal me.

FEILER: Pilgrimage, no matter the destination, is a way to mark time.

The places are largely unchanged.

It's the pilgrims who do the changing.

It's the final night of Sukkot, and Ahava has invited friends to dine with her in her Sukkah to hear her decision.

Her first stop is the market.

Do you have a certain set of places that you like to go to?

Sure I do.

I have my cheese guy, and my carrot guy, and my hummus guy and my wine guy.

I feel like part of being a local is knowg who your particular favorite people are, definitely.

Wow, it smells delicious.

FEILER: Food is central to all religious festivals.

In Judaism, after Jerusalem was sacked, the family table assumed some of the symbolism of the Temple.

A place to experience the presence of God.

I've seen some halva in my day.

This is the sesame-based, but I've never seen it like this.

I mean there must be 50 flavors here, it's like an Italian gelato spread.

This is coffee?

This is coffee.

Amazing, this is sweet nuts, Strawberry.

Strawberry, it's like cheesecake.

ZAREMBSKI: We're going to have lots of close friends.

I'm sure there will be lots of song, lots of good food, and lots of community, gathered in a really small space and there is an intimacy that exists there that I really look forward to sharing with everyone.

I'm going to wait right here and use all my restraint not to eat fig until we're under the sukkah, how about that?

Exactly.

These are pretty great looking.

FEILER: Sukkot teaches a valuable lesson about religious quests.

Some sacred journeys are grand, involving years of planning and months of travel.

But they don't have to.

Every believer is on a journey of some kind.

Sometimes, all it takes is to pause amidst the chaos, gather with friends and create a moment of connection.

(speaking Hebrew) FEILER: Everything I'd ever heard in my life about the feival of Sukkot has focused on the construction, but the longer I'm here, the more I realize it's less about the construction and it's more about the space that the construction creates.

There's a lot of Jewish law that gets very nit-picky about how we're going to go about doing things, but it's usually all this detail that goes into creating a place where beautiful things can happen, where holiness can happen.

Which is so interesting because that's what we're doing in Sukkot.

We're leaving our space and going into a new space.

What you're saying is the tradition builds in the idea of these mini journeys in the course of the year?

And yet at the same time, we live in a moment when the idea of generating your own faith, of creating your own belief system, of going on a journey, is very popular.

ZAREMBSKI: This is the difference between organized religion and spirituality.

How much are people willing to... make hard choices to go on a journey, an enormous journey that will shift the trajectory of your life.

FEILER: As Sukkot draws to an end, Ahava has made her choice.

Though she'll always have a foot in both worlds, her future is here.

I'm not 100% Israeli and I'm not 100% American.

I do think I'm a perpetual pilgrim, and now I'm starting to ask myself, what does this mean?

What it looks like it may mean is to come back in February, and possibly with a one-way ticket.

Part of living in the modern world is this blessed capacity to go back and forth and not feel like either has to be permanent or forever.

FEILER: The pilgrimage ends, but the journey does not.

The night after Sukkot finishes, Jews again gather before the Western Wall to celebrate the holiday of Simchat Torah, when the annual reading of the Torah ends and the new year begins.

The questions never cease.

LAZER MANGEL: We finish the entire Torah scroll, the five books of Moses, every year.

We read one chapter a week, and then we just finished it tonight, so we celebrate.

Within the same ceremony you read the ending of the book and then you scroll all the way back to the beginning, then start over.

(singing) While I feel out of place with the dancing and with the celebration itself, I still feel like I belong here.

It's conflicting, but it's my people.

It's different.

LEIBEL MANGEL: In America, the dream is to come here to be able to celebrate this holiday here.

For us, this is the holiest place in the world, so where else better can you do it than at the Western Wall?

(singing) FEILER: I've been on pilgrimages all over the world in many different faiths and the one thing they all have in common is they give the pilgrim the chance to escape the ordinary and encounter the extraordinary.

A pilgrimage at its core is a gesture of action, and the words pilgrims use capture this physicality.

They feel a deeper connection to their faith, they feel closer to God.

Their beliefs are less abstract, more concrete.

In a world in which more and more things are digital and ephemeral, a sacred journey gives the pilgrim the chance to experience something real.

I'm in the Arabian Desert, home to one of the great pilgrimages in the world, where for thousands of years people have come to answer the call of Abraham and celebrate the worship of one god.

Coming to Mecca on the Hajj is a duty and privilege for all Muslims.

MAN: I truly was alone with God in a sea of five million people.

FEIL: The Hajj, next time on Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler.

Find more information and exclusive video on Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler at pbs.org/sacredjourneys.

Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler is available on Blu-ray and DVD.

To order, visit shoppbs.org or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Ep3 | 1m 35s | Travel with American pilgrims to the holy city of Jerusalem. (1m 35s)

Notes from the Field: Tech at The Western Wall (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 2m 36s | Modern technology meets ancient religious rituals at the Western Wall in Jerusalem. (2m 36s)

Notes from the Field: The Etrog Man (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 3m 28s | Meet the Etrog Man in Jerusalem, Israel. (3m 28s)

Jerusalem's Second Temple Compound (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 2m 48s | Video resource from PBS LearningMedia. (2m 48s)

Notes from the Field: Brian's Story (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 3m 4s | Meet American pilgrim Brian Kwan traveling in Israel. (3m 4s)

Notes from the Field: Church of Holy Sepulcher (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 3m 22s | Watch the centuries-old tradition of the opening of the gates. (3m 22s)

Notes from the Field: The Arbel Cliffs (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 2m 13s | View the Sea of Galilee from the Arbel Cliffs. (2m 13s)

Notes from the Field: The Sukkot Quiz Show! (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 3m 4s | Try your hand at the Sukkot quiz! (3m 4s)

Three Religions, One City (Jerusalem)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep3 | 3m 59s | Video resource from PBS LearningMedia. (3m 59s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.