Osun-Osogbo

Episode 6 | 54m 21sVideo has Closed Captions

Premieres Tuesday, December 30, 9/8c.

The festival of Osun-Osgobo, which takes place every year in Osogbo, Nigeria, celebrates the Yoruba goddess of fertility, Osun. The festival renews the contract between humans and the divine: Osun offers grace to the community; in return, it vows to honor her Sacred Grove.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.

Osun-Osogbo

Episode 6 | 54m 21sVideo has Closed Captions

The festival of Osun-Osgobo, which takes place every year in Osogbo, Nigeria, celebrates the Yoruba goddess of fertility, Osun. The festival renews the contract between humans and the divine: Osun offers grace to the community; in return, it vows to honor her Sacred Grove.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Sacred Journeys

Sacred Journeys is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

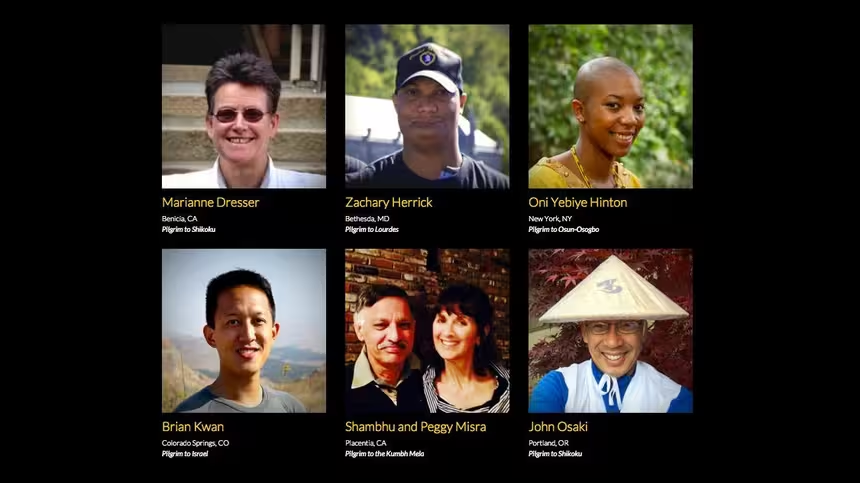

Meet the Pilgrims

Meet pilgrims from the Hajj, Shikoku, Jerusalem, Lourdes, Kumbh Mela, and Osun-Osogbo pilgrimages.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipI'm in Western Nigeria, the heart of the Yoruban people, where every summer, thousands of people gather in this sacred grove in the town of Osogbo.

FEILER: With 100 million worshippers, this is one of world's ten largest religions.

WOMAN: We pray with singing, we pray with bells, we pray with dancing and having fun.

FEILER: Carried to the New World by slaves, the faith is experiencing a renaissance among their descendants.

MAN: Although we left Africa, Africa never left us.

FEILER: But when they come back here, what will they find?

And what will they feel?

I'm scared, I'm excited, I'm overwhelmed, but I'm here.

FEILER: Today, organized religion is more threatened than ever, yet pilgrimage is more popular than ever.

I'm Bruce Feiler.

In this epic series, I travel with American pilgrims on six historic pilgrimages.

I bathe in the rivers of India, dance in the heart of Africa, cleanse in the waters of Lourdes, trek through the temples of Japan, and walk in the footsteps of prophets in Mecca and Jerusalem.

I attend some of the most spectacular and moving human gatherings on Earth.

And I ask, what can these journeys tell us about the future of faith?

FEILER: In Miami, Florida, worshippers gather for a sacred ceremony holy to Yoruba religion... a ritual offering to the goddess Osun.

This ceremony is from a rich tradition called Orisa that began in West Africa and has become, in many forms, one of the ten largest religions in the world, with 100 million practitioners.

Nathaniel Styles is a priest.

STYLES: Orisa worship is not just religion, it's a culture, it's music, sacred dance.

It's really a lifestyle much more than solely a form of worship.

FEILER: Orisa worship spread to the Americas when millions of West Africans were sold into slavery.

Today, the faith is being revived in Afro-Caribbean and African-American communities from Brazil to Boston.

It's popular enough in Miami to have a neighborhood named after the Goddess Osun and shops that carry sacred objects.

STYLES: When the Africans were brought over through the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, the spirituality of the various African cultures was combined.

And what happened was, in order to be able to practice, it became necessary that African energy was veiled behind Catholicism.

FEILER: Nathaniel Styles has been practicing this faith for decades.

Like other Americans with roots abroad, he feels called on pilgrimage to his ancestral land to find the roots of his identity.

STYLES: For any Orisa practitioner, the ultimate goal is to go to Yorubaland, to go to the source.

FEILER: Lagos is Nigeria's biggest city, the heart of the Yoruba people.

It's the entry point for pilgrims from around the world, traveling to the Osun Osogbo festival, held every August.

FEILER: Lagos is one of the fastest growing cities on the planet.

And yet, as I'm finding, it can't really handle the growth.

It's chaotic, it's overcrowded.

Still, behind a few of these buildings, you can find a pocket of the past.

(rooster crowing) And for the pilgrims who come here, one of their goals is to link these two, to build a bridge between the modern city of today and the traditions of African culture.

FEILER: Alafia Stewart and Oni Yebiye Hinton are Americans in Africa for the first time.

Raised in the Orisa tradition, they're here to be initiated as priestesses and attend the Osun festival.

(horn honks) FEILER: The initiation will last three days and involve prayer, head-shaving and animal sacrifice.

Recent college graduates, Alafia and Oni are enthusiastic, but also wary.

STEWART: As the music was playing and the gates were opening, it felt like the secret garden, like we had arrived.

Like, there was no turning around, there was no rethinking it.

My eyes are open, my heart is open and I am here.

I'm scared, I'm excited, I'm overwhelmed, but I'm here.

YEBIYE HINTON: It's like my head is swimming with so much energy and so much positivity and it's like it's overwhelming.

I feel like I have a knot in my chest.

My heart's beating so fast, but it's...

It's amazing, it's so awesome.

FEILER: Like many who undertake a personal journey back to their roots, Alafia and Oni are at a time of transition in their lives.

STEWART: There were so many things going on that I didn't like, that I didn't want, and I felt like, "I need more clarity, I need to understand where I'm going."

And this is the ultimate opportunity to do that.

(people responding to leader in local language) FEILER: The initiation begins by greeting local deities, called Orisa.

For Alafia and Oni, it's the start of their larger journey-- contemplating their role in the world.

BABALAO: Here in Yorubaland, we have the opportunity to rewrite our destiny.

And to do something about your destiny, you need initiation.

And that is one of the reasons why you are here.

Now, you are here to connect yourself with your orisa.

So let us greet egbay.

(speaking local language) (drumming and singing) FEILER: Among the priests here is Lloyd Weaver, an American who's lived in Nigeria for the past 30 years.

WEAVER: The traditional religion of the Yoruba people is very similar to Christianity in that it worships one god.

In Christianity, there's the father, the son, and the holy ghost, and they are three aspects of one god.

Yoruba traditional religion, you have the same thing except there's 401 aspects of one single god.

These aspects of God are called orisa.

And the African Americans that are being initiated today are being initiated to an orisa called Osun.

Osun, very, very simply, is God's love.

FEILER: Most of the three-day ceremony will take place in secret, as the initiates must leave behind their old selves.

STEWART: I have to cut off my hair.

It's a little nerve-wracking because I have to give up societal ideas of what it is to be beautiful.

It's like I've had short hair but I've never had no hair.

And I do struggle with that part of my vanity.

FEILER: A few miles from where Alafia and Oni are undergoing their initiation, three of their friends from the United States are also preparing for the festival.

Funlayo Wood, a Ph.D. candidate in African Studies at Harvard, is already an Orisa priestess.

WOOD: We're buying fabric to get made into outfits.

It's always an exciting, fun thing to do when you come to Nigeria.

There's just a certain sense of style and flair, and looking tailored is a big part of the culture that I really enjoy.

FEILER: Gillian Johns and Sandy Placido both teach at American universities.

JOHNS: Do you mind if I get the same fabric?

Oh, no, I don't mind at all!

FEILER: Though neither was raised in the Orisa tradition, they've come here to better understand their African roots.

PLACIDO: I was raised Dominican in New York City and baptized in the Catholic Church, but one of the things that was present in our household is having altars, candles, praying to saints.

As I've learned more about Orisa faith, those same Catholic saints that we were praying to actually have correlates in the Orisa religion.

JOHNS: I come from a background where I was denied my cultural roots.

I was a transracial adoptee and grew up in an all-white community and was labeled as Indian, East Indian, as a hard-to-place baby.

So it's been a long journey for me to sort of claim-- I'm biracial-- but to claim my black side and my culture and heritage.

FEILER: When the slave trade ripped through Western Africa beginning in the 15th century, millions of men, women and children were taken from this land, shipped to the Americas and sold into bondage.

Families were torn apart.

The slaves' identity, culture and religion were taken from them.

And in many cases another religion, usually Christianity, was imposed on them.

WEAVER: It's said that over half of the slaves that were carried to the Americas-- and we know there were ten million of them-- actually came from the coast of what is now Nigeria.

Overwhelmingly, most of those were Yoruba.

Practicing African religion was outlawed during the days of slavery, so you had to go underground.

FEILER: The Yoruba in exile kept the faith alive for centuries, in part by integrating some of its rituals into their practice of Christianity.

FEILER: There's an irony here.

The slave traders, instead of killing the religion, by bringing millions of people across South America, the Caribbean and North America, they actually spread the religion and allowed it to take root in new places.

FEILER: Diedre Badejo is a professor of African cultural history in Baltimore and also a priestess of Osun.

A frequent visitor to the festival, she prepares by buying supplies at the market.

BADEJO: The items I need to thank my personal spirit for blessing me so far, but also to ask for blessings going forward.

JACOB OLUPONA: African Americans have played a very, very important role in the revival of Orisa traditions.

It's a movement back and forth that has enabled us to recognize the importance of this tradition.

And some of us do feel that if it continues, there will be a kind of a reawakening in Nigeria.

FEILER: Nowhere is this awakening stronger than in the city of Osogbo, 120 miles northeast of Lagos, in the heart of Yorubaland.

People from around the world flock here every August for the annual festival that celebrates Osun.

The 12-day event begins with the lighting of an ancient lamp that dates back to the founding of the city.

These 16amps represent Osun and the Yoruba kingdoms.

Osun is the protector of Osogbo, so the whole town comes out.

They're happy Osun is going to represent them for a whole other year, and it's a joyous occasion.

BADEJO: It's multi-religious.

Some people will be practitioners, some won't.

Some belong to other major faith traditions, but this is not about religion tonight.

Osun is the patron of this town.

It's like going to a St. Patrick's Day parade.

You know, you don't have to be Catholic to enjoy St. Patrick's Day.

FEILER: The event climaxes when the king of Osogbo and other political leaders arrive to welcome the goddess with a dance around the fire.

BADEJO: They all come together to make sure that that union between the political rulership and the spiritual rulership is maintained and celebrated in public.

It's an affirmation of the founding of the city.

FEILER: To come on this pilgrimage, like any around the world, is to experience firsthand that elemental relationship among the people, the land and the gods.

The place where that union between the people and Osun was first forged is just a mile away in a sacred grove on the banks of the Osun River.

It's one of the most revered spots in all of Africa.

The Osun goddess, who we call Yeye Osun, is the good mother.

She is the deity through whom all life flows.

FEILER: In the Yoruba origin story, Osun and 16 male deities were sent to create the world.

When the men ignored Osun, everything went wrong.

Only after the male gods learned to work with the goddess did the world come into being.

BADEJO: It shows a balance between male/female energies.

Men cannot do it alone, nor can women.

FEILER: Diedre first came to the grove in 1975 as part of her graduate studies.

BADEJO: I can't really tell you what I felt in the depths of myself about being here.

I would come down here by myself because it was calming.

I could just feel myself just flowing with this river.

And the connection that I felt was very, very deep.

And it's lived with me since then.

FEILER: Alafia and Oni have been in seclusion for several days in the most private, sacred part of the ceremony.

Only initiated priests are allowed to attend.

STEWART: I've given my hair to the orisa for new blessings.

When my hair was cut, it was symbolizing all of the negative that's happened before going away, so that everything that's new will grow stronger, be more blessed and have more ase.

YEBIYE HINTON: We have been reborn.

We have stepped into our new life, our new spirituality, our new being.

I haven't been sleeping.

You know, crying most of the time, but crying tears of joy.

FEILER: The final part of the ritual is a public celebration.

Alafia and Oni's American friends assemble to witness their induction.

As in many religions around the world, the holiest moments of Orisa worship pay homage to the gods with animal sacrifice.

STEWART: I think of it as being no different than kosher meat.

It's been prayed over, and the fact that that animal has given its life for my life and given its life for me to be uplifted, I'm so thankful to these animals for what they've done for me.

FEILER: For outsiders, the rite can be unnerving.

PLACIDO: I have not seen a goat sacrifice before.

I mean, that's obviously where the food we eat comes from, but I just had take a second and step back, and it was fine.

But it was a little surprising, for sure.

FEILER: A key part of Yoruba religion is foretelling the future.

The divination is performed by priests who use natural objects to interpret a series of texts called Ifa.

Ifa is the essential scripture of the Yoruba people.

It's about four times as big as the Holy Bible.

Ifa includes the sacred text.

But it also includes history, genealogy, study of herbal medicines.

It has elements of psychology.

So this is why we call it an encyclopedia of Yoruba knowledge.

FEILER: By casting nuts and shells, the priest identifies a passage of Ifa that might help the worshiper.

The process is like Tarot or I Ching, or any encounter where a priest offers guidance to a person in need.

BABALOA: Now you got your Ifa.

You have all the power in the world.

STEWART: This is probably the most important moment of my life because Ifa gives us the opportunity to rewrite our stories the way we want to and pray for the things that we want.

FEILER: Sacred sites in Yoruba religion are spread out all across Nigeria.

FEILER: This is the sacred city of Ile-Ife, the Yoruban Eden, where the religion holds that human kind was first created.

But while there is this overarching God, there's also hundreds of smaller gods to war, rain, farming.

And each one of those has its own shrine.

FEILER: Behind the crowds, traffic and pollution of everyday life, scores of temples and shrines keep the ancient traditions alive.

One of the oldest and most sacred holy shrines is the Staff of Oranyan.

It pays homage to the son of Ile Ife's legendary founder, who in the 12th century first carved out the 16 great Yoruba kingdoms of West Africa.

These city-states created one of the greatest civilizations in all of Sub-Saharan Africa.

For hundreds of years, Yorubaland was a pinnacle of African life, art and culture until the region was undermined by colonization and the slave trade.

For African Americans who've heard stereotypes of their homeland, reconnecting to this rich tradition is a chief draw of the festival in Osogbo.

I'm heading to the event's centerpiece, a place that defies stereotypes-- Osun's Sacred Grove.

FEILER: All great pilgrimages have at their end point an extraordinary destination like this.

The word that comes to mind for me in this place is "melting."

There's a kind of droopy, drip castle-y otherness to the sacred grove.

FEILER: While the grove is the site of Osun's most sacred shrine, many Yoruba deities are also depicted here.

Some of these sculptures are centuries old, but most were created during a revival that began in the 1950s.

As the tradition faced pressure from colonialism and outside faiths, a European sculptor named Suzanne Wenger worked with local artists to restore the grove.

Because of them, 200 acres are now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

So why is this particular spot so important?

The annual celebration of Osun has always taken place here because of Osun's role in the settling of human society.

FEILER: The festival's main purpose is to renew the contract between humans and the divine.

Osun offers grace to the community.

In return, it vows to honor her home.

BADEJO: Part of the treaty was to preserve this grove.

Osun said, "If you settle in my grove, "you cannot hunt the animals here, "you cannot fish in the lakes, "you cannot cut down the trees.

You have to respect this as a sacred grove."

FEILER: I love this part of the story.

There is this connection in this place between the gods and people.

BADEJO: There's a Yoruba proverb that says... (speaking Yoruba) which means that if there are no human beings, there are no deities.

There's a very powerful message there, right?

Which is that the world can only thrive if humans and the gods are working together.

Yes.

The gods help to enforce humanity's role in ensuring thatature and human beings continue to thrive and survive.

FEILER: The pact between humans and the goddess will be renewed by the king on the festival's final day.

The process begins days earlier with a ceremony of the crowns.

The current king claims direct descent from the city's founder, who made the original bond with Osun.

FEILER: Tradition says 18 kings have ruled in Osogbo.

During the ceremony, their crowns are laid out to be blessed by the goddess.

Beading is a Yoruba sacred art, a symbol of the connection between earthly and heavenly rulers.

The crowns are blessed, and prayers are made to Osun for the town's protection.

The rituals have changed little since slavery shattered this community and spread its believers around the world.

WEAVER: During the 1960s there was an identity movement that came on as a part of the civil rights movement.

We wanted to know more about Africa.

We wanted access to those things that we had been denied.

FEILER: Which is one reason pilgrimages to this place have become so popular among Americans.

The festival offers the chance to touch rituals and people that trace back to the earliest days of the faith.

Each pilgrimage becomes a portal to the past.

In Yoruba culture, music and dance are direct pathways that connect the physical world with the godly one.

An Osun dance troupe kicks off the ultimate stage of Alafia and Oni's initiation.

In the climactic moment, the essence of the goddess is transferred through a crown into the head of each priestess.

WEAVER: What makes a priest a priest is, your body becomes a temple of the orisa.

And that orisa resides within you.

YEBIYE HINTON: This has been my way to encounter who I'm supposed to be.

To make sure that the path of destiny that I walk on is the path that I'm supposed to be on.

STEWART: I didn't know who I was until this process.

I had an idea, but I wasn't solid.

I'm still growing, I'm 26.

I'm still trying to figure my life out.

But this has definitely given me direction and solidified who I want to be, and I'm taking conscious steps towards that.

I'm becoming myself.

I'm becoming the person that I want to be.

FEILER: In any sacred journey, the travel, the extravaganza, are not the true setting.

The real landscape is not the one you can see at all.

It's the one inside you.

It's the geography of yourself where the spectacle truly unfolds.

As a senior priest in the tradition, Nathaniel Styles has devoted his life to sharing the beauty of Yoruba culture.

A frequent visitor to Nigeria, he works closely with local artisans to export their sacred crafts to the West.

Many are created in the back streets of Osogbo as they've been for generations.

Like these delicate brass prayer bells.

Objects like these help bring the tradition to life, he believes, and invite outsiders to learn more about their use.

FEILER: One thing you see around the world are people coming back to religion.

There's lots of different ways.

What is the most popular way to come back to the faith?

STYLES: It's through the music and dance.

We say, culture is the mandate of your destiny.

So it's not until you have a thorough understanding of your culture, your history, your roots, that you're able to evolve as a complete person.

FEILER: Someone says to you, "I've got my job, "I've got my family, I like my life.

Why do I want to go back to the past?"

What do you say to them?

STYLES: That history is the reflection of all things that have been and all things that will be.

So there are many other people like myself that are looking for a deeper meaning that reflects our experience as people of color.

FEILER: A central point of pride in that tradition is the batik fabric used in ritual garments.

FEILER: So when you put on these clothes, it's not just getting dressed.

STYLES: No.

The colors usually depict the orisa that one is initiated to.

So when you see the yellows and golds, it's Osun.

Green and brown is Ifa.

So there's a spiritual significance to the various colors that are worn.

FEILER: There's a wonderful legend about the original pact between the king and the goddess.

When the king took refuge in Osun's forest, he chopped down a tree that fell and broke her personal dye pots.

To make amends and secure her protection, he agreed to always honor her with an annual festival.

FEILER: Osun is not just about beauty in general.

She's specifically about this particular skill.

STYLES: Yes, she is.

Indigo is owned by Osun.

And during the period of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, indigo was a commodity that surpassed the value of gold.

FEILER: Those who wear these garnts pay special tribute to the goddess.

But those who make them are her personal disciples.

STYLES: So this is their ministry, you can say.

They're expressing and venerating Osun in the process of their work.

JOHNS: This is gorgeous, I like this style.

FEILER: Carrying the Yoruba fabric they bought in Lagos, Funlayo, along with Sandy and Gillian, meet with a local seamstress.

They'll soon have ritual dresses to wear at the festival's finale.

WOOD: You'll find people, no matter what religion they are, wearing Yoruba clothing.

So they could be Yoruba people who are Christian, Muslim, Orisa worshippers, it doesn't matter.

But for American practitioners, wearing these things back home has a different type of significance because even if you're not in the tradition, people may assume you are.

And it's a way to kind of identify yourself as someone who has an African cultural orientation, if not specifically Orisa tradition.

FEILER: Now that Alafia and Oni are Osun priestesses, they make their first visit to the grove.

YEBIYE HINTON: Walking into the grove is overwhelming.

It's magical.

FEILER: When you put on these clothes, do you feel transported in some way?

The crown definitely makes me feel beautiful.

You know, having the tassels, and then being able to see through those, and seeing the world kind of through honey.

That's what it looks like.

Everything has a certain sweetness, has a certain beauty.

STEWART: We're brides of the goddess, so it's like our veil is something that you would see in a wedding, almost.

And it's like the bride is beautiful and everybody's attention is on her and everything like that, so it's just, it's beautiful.

It makes you feel beautiful.

YEBIYE HINTON: The bell of Osun is to send the message straight to her ears.

It's almost as if saying our prayers and ringing the bell is speaking directly to her, so she can hear us clearly and understand what we're saying and what we are praying for.

My bell makes me speak louder because I tend to pray quietly and, you know, you're supposed to pray as loud as you can so it can be heard.

So I try to talk over the bell, so it kind of helps me pray even more.

STEWART: Standing at the river's edge and touching the water for the first time brings an overwhelming sense of calm.

Like, everything that we've accomplished so far in our initiation, and then coming here to where Osun stays is like we're coming home.

FEILER: Yowere raised African American.

Many of your relatives were taken from this place or places like it by force.

You are coming back by choice.

Tell me about that.

I actually consider myself to be an American African because it wasn't by choice.

So much of our knowledge was taken away, so much of our religious faith was taken away.

Our names were taken away.

We were blank canvases.

And there is no power in not knowing who you are or not knowing where you come from.

This journey, coming back here, means that I'm taking back that power, I'm taking back that identity and I'm walking in that.

I'm walking in who I am.

FEILER: In Osogbo, the sacred art of the grove is echoed in the home and temple of the high priestess, known as the Iyaosun.

She began her training for the priesthood at age three and has spent her entire life serving the goddess.

BADEJO: The Iyaosun is the caretaker of Osun, of the Osun Festival, of the Osun Grove, and of the knowledge of Osun.

(singing) She learns from a very young age the oral tradition, that is the poetry, the history, the songs, and the rituals that accompany Osun practice and worship.

FEILER: For the past few weeks, one of the Iyaosun's primary duties is preparing the adolescent girl who will perform the most important ritual on the festival's final day.

The arugba, as she's known, will carry the town's sacrificial offering through the city, into the grove, to the river itself.

Chosen from the extended family of the king, she must be a virgin, symbolizing her purity.

FEILER: As the goddess of fertility, Osun is also the deity of children.

It's one reason so many women in particular travel so far to worship her.

To come to this festival is to renew your own sense of possibility, to open yourself up to the hopes and dreams that may have dimmed with time and age.

The festival has been taking place mostly indoors until now.

But the day before the final procession, the streets fill with anticipation.

Now suddenly for miles you have all these stalls.

You've got gin used for sacrifices, you've got yams the size of elephant feet, and all this fried food.

You've got fish heads, peanuts, boiled eggs.

It's like this whole festival has popped up virtually overnight.

FEILER: Whether you live in Osogbo or have come halfway around the world, the energy is contagious.

Some pilgrimages are about quiet contemplation.

This is African.

It's about drumming and dance-- even if you're not very good at it.

The excitement is also building in the Sacred Grove, where the holy shrine and pavilion are being readied for the crowds that will soon descend.

FEILER: I've stumbled onto what is a common scene in the grove.

You have a group of young guys and they're going to make a sacrifice to Osun, the goddess of the river.

What they've done is they've taken off the head of the chicken and they are dripping the blood onto the head of the young man.

So at the climactic moment of the sacrifice, they take the body and they toss it into the river.

That's the official offering of the animal to the Goddess Osun.

FEILER: Funlayo and her friends arrive to spend some quiet time in the grove before the crowds.

FEILER: You study the spread of African people around the Americas.

Do you feel that the traditional religions of Africa can unite these otherwise disparate people?

I would say that the peoples actually have a lot in common, but I think really, a lot of the work is realizing our similarities.

Religion definitely is a thread, but with religion comes the music, comes the ritual, comes a community.

That's why the Osun Festival is so important to me, too, because she represents a figure who can bring communities together.

FEILER: So tell me about what it means actually coming to this place.

WOOD: We can see all the ways in which we are connected.

And it's important for those who are here in Nigeria to see us come and to know that their traditions are still alive and flourishing, because unfortunately the tradition is under attack, even here in its birthplace.

So when the devotees here see people coming from everywhere around the world, still worshipping the deities who were born here, it gives them a renewed sense of energy and pride.

FEILER: Even in Osun's home city, Orisa faith is under threat from outside religions.

There's a church on every corner, a mosque on most streets.

Locals have Christian names and kids attend parochial schools.

FEILER: I have to say, I'm stunned by this.

And it raises a question which is, how can this traditional religion live side by side with these more contemporary ones that in many ways are trying to eliminate it?

OLUPONA: Christianity and Islam.

They are two monotheistic traditions that preach about the exclusive God.

You know, Islam, radical monotheism, doesn't allow any other to share in the glory of Allah.

Or Christianity-- outside the church, they say there is no salvation for other people.

The Evangelical Christian traditions are having a significant impact on indigenous religion.

They're discouraging people from practicing Orisa tradition.

FEILER: Each year Funlayo and others organize workshops to empower local Orisa believers to fight back against this encroachment.

WOOD: Church and religion is about so much more than just worship because they offer social connections.

Some of the churches unfortunately have even gone so far as to literally tell traditionalist youth, "Hey, we can get you a job if you'll convert to Christianity."

And so we're trying to really make it so that traditionalists are able to build their own connections and won't feel that they have to desert their religion in order to progress in life.

FEILER: So does this traditional faith have a future in its own homeland?

To help answer that question, I'm off to visit a local priest who's offered to do a divination on me.

I'm shocked to discover that even he lives next door to a church.

Come on, come on.

(speaking Yoruba language) What is your name?

My name is Bruce.

Bruce.

This is Ifa.

You take it, you touch your head and your chest.

You make your prayer.

FEILER: In the West, so many of our religious rituals now take place in big buildings, where worshipers are far removed from holy objects and surrogates perform sacred duties.

Here, everything is more immediate and intimate.

It feels more personal, more visceral.

If a divination was made for your uri-- head.

Of my head?

Bring your head.

FEILER: The priest tells me I have to open my mind in order to appreciate the final day of the festival.

And speaking of openness, I ask if his tradition is being threatened by other religions moving in next door.

How can the spirit of that church and the spirit of this temple live side by side?

You can go to anywhere in the world.

Even the Muslims, Christians... we are one.

The way we worship our God might be different, but we are only calling one God.

Let me be frank with you.

The people that I attend to every day is Muslim and Christian.

They do come here to the temple.

They know, when they need help, they know the right place to go.

FEILER: It's precisely this ability to coexist with others that will likely allow this tradition to survive.

Orisa has a much higher tolerance for other faiths than the more triumphant religions have for it.

And just as it survived slave owners who Christianized their captives, so it will surely find a way to adapt to those same tactics.

As the moon rises before the big day, the streets are still crowded.

Drums pound through the darkness.

Near midnight, Nathaniel Styles brings me to the sacred shrine where the 14-year-old virgin princess is being readied for the procession.

Tomorrow, she'll carry the town's offering down to the river.

The priestesses around her are warm and welcoming.

The mood is high.

Stepping in here feels like entering the Yoruba holy of holies.

There's a pulsing fervor to the place.

Also, it's hot, humid and becomes increasingly intense.

Go away.

FEILER: At exactly the moment I felt myself getting almost light-headed, this priest came through and started elbowing me aside and said, "You're not allowed in here."

He actually kicked me out because he said it's just so important and he doesn't want me... and look at you, you're drenched in sweat.

What's it like for you to be in there?

Did it feel like that holy of holies?

Most definitely.

A sudden burst of energy and heat.

Heat, exactly.

Very intense, electrifying energy.

But it's not just external heat, also... No, it's internal, very much so.

FEILER: That excitement only builds overnight as the city of Osogbo and the Yoruba people ready once more to renew their timeless bond with the goddess of life.

As people pour into the city, the military beefs up its presence, a reminder of violence between Muslims and Christians a few hundred miles to the north.

Here, the mood is undimmed.

Behind me is where the arugba, the young princess, has been closeted for weeks, being prepared for the occasion.

In a few minutes she's going to walk outside that door prepared to lead the procession, and suddenly have the eyes of the Yoruban people on her.

It's quite a lot of pressure for a 14-year-old girl.

FEILER: The streets fill with drumming, dancing, celebration.

With thousands of others, I begin the mile-long walk from the city center to the sacred grove.

Sandy and Gillian, wearing their new dresses, are doing the same thing along with Funlayo.

Alafia and Oni will come along later with the arugba.

FEILER: We're entering the grove now and you can start to see everybody with all the religious paraphernalia that you need.

So these women here are carrying mats and all the materials for the divination.

And almost everybody walking into the grove has a bottle, a jug, or a huge can that's now empty that they're going to fill with water.

FEILER: Like the high point of many religious journeys, this event feels like one part sacred rite, one part carnival.

It's religion as communal bonding, homecoming for the Yoruba people.

JOHNS: This is incredible.

I've never seen anything like it in my life.

The energy, the music, the drumming.

I'm just kind of speechless about it.

Certainly, the religion that I grew up in, people don't express themselves this way.

I grew up in a very conservative Christian church and this kind of celebration, exhilaration, would have been really frowned upon.

WOOD: The Orisa tradition is very, very rich, vibrant, energetic, all of that.

We don't pray in silence, we pray with singing, we pray with bells, we pray with dancing, and having fun.

FEILER: While thousands strut their way toward the river, thousands more flock to the palace shrine to greet the arugba.

The young maiden is about to appear in public for the first time in more than a month.

Everything that takes place today is carefully choreographed-- the movements, the dress code, even the arugba's security.

BADEJO: The arugba is protected by the Osun priestesses.

Around them are guards who bear whips, who keep the crowd back.

And there's sort of a performance that goes on with young men who are being hit with the whips.

It's part of a drama that is played out, but it also signifies that people should move back.

FEILER: At mid-morning, with viewers hanging from every window and the streets packed, the arugba finally steps outside.

She's hidden beneath a bright canopy and carrying the sacrificial offerings she'll take to the river.

Diedre Badejo is among the priestesses who surround the arugba.

The group starts the procession that will take more than two hours to bring them into the grove.

Among the group are the new initiates, Oni and Alafia.

STEWART: This is beyond anything at I thought.

You know how you see pictures of festivals and parades and things like that?

They have nothing on this.

This is intense.

There are people everywhere, everywhere.

Look at our numbers, look how many of us there are.

It feels good to be amongst each other and to celebrate with one another.

FEILER: As the crowd approaches the most sacred area, worshipers erupt into a unified cheer, like fans at a sporting event.

The gesture signifies clearing out the old to make room for the new.

WOOD: Part of the festival is cleansing and renewal.

So when you do that, you're warning any negative energy to go so that the blessings of Osun can come in.

It does seem to work.

When you're doing it with the crowd, you actually do kind of feel, like, something happening when we're all doing it together.

So it seems to be working so far.

FEILER: The crowd around the arugba grows more congested as she nears the river.

Spectators cheer.

Everybody wants a glimpse.

The spotlight on her must surely feel intense.

The king's entourage arrives at the river bank first, headed by armed guards.

The scene is chaotic, almost dangerous at times.

Guns go off almost constantly.

A few times, I feel unsafe, about to be crushed.

Here comes the high priestess.

FEILER: As the arugba and her priestesses reach the enclave, the crowd erupts.

Suddenly the tension breaks, replaced by jubilance.

The young girl will bear her offering to Osun with the hopes of the town, and they want their prayer delivered with joy.

Sacred rivers are central to many religious traditions, from the Nile in Ancient Egypt to the Ganges in Hinduism.

Here, though, the river is so holy, you're not allowed to bathe in it, only cleanse with it and make sacrifices to it.

The river is the goddess.

Now we're going to offer cola, gin and prayers to Osun.

We're going to ask her for blessings, report any problems that we have, and just thank her for all the blessings that she has already given to us.

And we're just hoping for what we call alafia, ire gbogbo, blessings all around, and health and long life.

That's the most important blessing.

FEILER: While Sandy and Gillian are still absorbing the experience, Funlayo knows what she treasures here.

It's the community of believers you build along the way, the power that comes from joining with others to raise a collective prayer.

WOOD: We believe in collective energy, so with the energy of everyone here, everyone's prayers are amplified by everyone else's prayers.

It's believed that the things that you pray for today will definitely, definitely be answered.

FEILER: Alafia, too, is moved by the unity of the crowd.

To her, it's a sign of the enduring power of Osun.

STEWART: When I'm walking down towards the river, I feel her here, I feel an energy.

It feels like a heartbeat.

It's probably a culmination of the people, the music, the sights, the sounds, but we're all here for Osun, so I equate that with Osun being here.

FEILER: The king and his court settle in to watch an afternoon of singing and dancing.

Diedre Badejo joins in.

For her, this day is a testament to the ongoing appeal of the religious quest.

BADEJO: I think that anybody who goes on a sacred journey, that ventures into another tradition, is a soul searcher.

They are seeking to find something else within themselves they're trying to reconnect to.

And you have many people who come here and connect with something greater than themselves.

And those people come back year after year after year.

FEILER: This is Nathaniel Styles' tenth festival.

What he's seeking is the touchstone for an entire people.

STYLES: One of the questions the press is repeatedly asking me is, why is African culture and tradition so significant to us as African Americans?

And the one thing I can say is, although we left Africa, Africa never left us.

Alafia, happy to know you, lovely to know you!

You, too.

Thank you very much.

Thank you for standingwith me.

We stand with you because we love you.

Oh, thank you, Baba.

STEWART: Having celebrated and worshipped here has given me a foundation for celebration and worship at home.

I don't have to be afraid to be who I am.

I don't have to be quiet about it.

I can stand up and say, "You know, I'm proud "to be a traditionalist, I'm proud to worship Orisa, I'm proud to do these things."

And taking what I've learned here and the warmth and the kindness of the people and the encouragement, I'm going to take that back with me, and hopefully my experiences will have encouraged others to seek their own truth.

FEILER: On a stretch of river away from the crowds, the final act takes place in secret.

The arugba delivers the people's offering to the river, and the king reaffirms the pact with Osun.

Yorubaland will live in peace for another year.

With the journey complete, Africa is renewed.

FEILER: For the pilgrims I met, coming here was incredibly meaningful.

Not just for their spiritual lives but for their identity as descendants of Africa.

You could feel them reclaiming their tradition, coming back to this place and saying, "These are my gods, too."

And there's great power in going on the sacred journey itself, standing in a holy place, taking ownership over your identity and saying, "This is what I believe, and I reaffirmed it here.

"” Find more information and exclusive video on Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler at: Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler is available on Blu-ray and DVD.

To order, visit shopPBS.org or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Notes from the Field: Arriving in Osogbo (Osun-Osogbo)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep6 | 2m 43s | Host Bruce Feiler arrives in the city of Osogbo, Nigeria. (2m 43s)

Notes from the Field: Osun's Sacred Bells (Osun-Osogbo)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep6 | 3m 39s | These sacred bells are a symbol of the Osun-Osogbo festival. (3m 39s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Ep6 | 1m 33s | Travel with American pilgrims to the Osun-Osogbo festival. (1m 33s)

Initiation of a Yoruban Priestess (Osun-Osogbo)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep6 | 5m 59s | Video resource from PBS LearningMedia. (5m 59s)

Notes from the Field: Meet the Arugba (Osun-Osogbo)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep6 | 3m 5s | This 14-year-old is the most important person at the festival of Osun-Osogbo. (3m 5s)

Notes from the Field: My Divination (Osun-Osogbo)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep6 | 3m 37s | Bruce receives an important message before the festival. (3m 37s)

Yoruban History and Diaspora (Osun-Osogbo)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep6 | 1m 58s | Video resource from PBS LearningMedia. (1m 58s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.