Shikoku

Episode 2 | 54m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

Premieres Tuesday, December 16, 9/8C

The Japanese island of Shikoku is the birthplace of the most revered figure in Japanese Buddhism, the monk and teacher Kobo-Daishi. For hundreds of years, a 750-mile pilgrimage route has circled this mountainous island, connecting 88 separate temples and shrines that claim connection to Daishi, also known as the Great Master.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.

Shikoku

Episode 2 | 54m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

The Japanese island of Shikoku is the birthplace of the most revered figure in Japanese Buddhism, the monk and teacher Kobo-Daishi. For hundreds of years, a 750-mile pilgrimage route has circled this mountainous island, connecting 88 separate temples and shrines that claim connection to Daishi, also known as the Great Master.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Sacred Journeys

Sacred Journeys is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

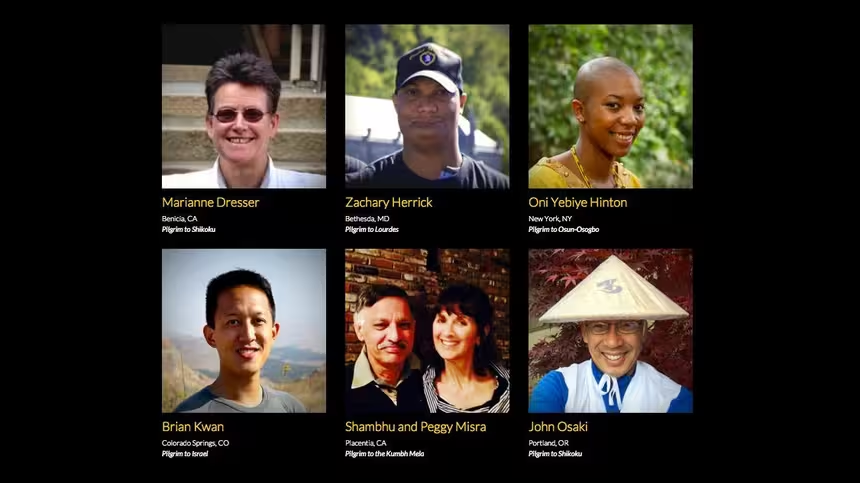

Meet the Pilgrims

Meet pilgrims from the Hajj, Shikoku, Jerusalem, Lourdes, Kumbh Mela, and Osun-Osogbo pilgrimages.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipFEILER: I'm in Japan to witness one of the world's great pilgrimages.

(chanting) Each year, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims from around the world come here to complete a rugged 700-mile journey, covering 88 temples.

JENN TSAI: At the end of the day, my feet always hurt.

MARIANNE DRESSER: Everything that happens on the way is equally important to reaching the goal.

FEILER: This historic Buddhist trail includes secret ceremonies, grueling climbs and for pilgrims, a deeply personal question.

What am I looking for?

What am I hoping to find?

STEVE WILLIAMS: It's a journey of learning about faith and what faith means to me.

FEILER: Today, organized religion is more threatened than ever, yet pilgrimage is more popular than ever.

I'm Bruce Feiler.

In this epic series, I travel with American pilgrims on six historic pilgrimages.

I bathe in the rivers of India, dance in the heart of Africa, cleanse in the waters of Lourdes, trek through the temples of Japan and walk in the footsteps of prophets in Mecca and Jerusalem.

I attend some of the most spectacular and moving human gatherings on earth.

And I ask, what can these journeys tell us about the future of faith?

I'm about to announce my arrival at the birthplace of the most revered figure in Japanese Buddhism, where every spring tens of thousands of pilgrims trek for weeks on end to catch a glimpse of enlightenment.

(bell reverberates) (men chanting) This journey is part of the ongoing search for meaning at the heart of Buddhism, the world's fourth largest religion with 350 million followers.

Here in Japan, Buddhism took on a unique popular form 1,200 years ago, largely because of the scholar monk known as Kobo Daishi.

Today, a 700-mile pilgrimage route retraces his footsteps around the island of Shikoku, where he was born and lived.

It's a treacherous journey, linking 88 temples.

On foot, it can take more than 45 days.

While most of the 200,000 pilgrims who come every year are Japanese, an increasing number are from the West.

Many are not even Buddhist.

I've come to find out what's drawing them.

Are they seeking adventure?

Personal insight?

Or something deeper?

At Temple 1, where most people begin, I ask the priest what inspires pilgrims to make such a difficult journey.

TRANSLATOR: A pilgrim is someone who wants to connect with Kobo Daishi.

They call upon the spirit for help when it is needed.

Human life is complex.

During periods of pain and transition, there's need for clarity.

At such times, pilgrimage is comforting, a chance to heal.

FEILER: Americans Jenn Tsai and Alex Fu recently graduated from medical school.

They aren't looking for healing, but they are at a time of transition before they become doctors.

So what question do you hope to get answered by coming here?

I think we all had sort of certain reasons we wanted to go into medical school, to help people, to satisfy our intellectual desires, things like that.

Now we're at another turning point in our lives where we now have responsibility to actually take care of people.

And I feel like a lot of the ancient traditions, you know, are about healing and self-discovery and there's a lot of things that we can learn from looking back in the past, and hoping to do some of that here.

It's a good time to kind of reflect on that and think about how we want to carry our lives from now on.

FEILER: Jenn and Alex have set an ambitious goal.

They want to walk the entire 700-mile route in just 38 days.

That's a week faster than the average.

Not everyone meets their goal.

Retired Marine Steve Williams is training in California for his second trip to the island.

Last year, he traveled from Temples 1 to 23 before injuring himself in a fall and heading home.

WILLIAMS: I'm not planning to do the whole trail this time, just from Temple 24 to 51.

It'll take me about a month to get that far.

A lot of people are athletic, probably don't need much training, but for myself, I need to lose the weight and get in shape because it's very arduous, you're walking 15-18 miles a day.

FEILER: Steve first became interested in the Shikoku pilgrimage in the 1980s.

WILLIAMS: After high school I joined the Marines and did 23 years, and I spent eight of those years in Japan.

I saw pilgrims walking and I decided I wanted to do it.

And I had forgotten all about it until I retired.

All my life, I've been like a lot of people, always living in the future.

I'll be happy when this happens, I'll be happy when I get this.

And I hope this journey will teach me to live more in the present and be happy with day to day and not living in the future.

FEILER: Another group of Americans has just arrived on Shikoku.

Their plan is to spend ten days hiking the most scenic parts of the trail.

Their leader is Japanese American John Osaki.

OSAKI: I was raised as a Catholic, one half of my family, and the other half was Jodo Shinshu Buddhist, so I went to Catholic church every Sunday, and then temple for important days.

So I guess I feel like I can flow very easily between both of them.

CHRISTOPHER LOH: I'm not a Buddhist myself, but I like the Japanese landscape, I like their architecture, I appreciate the companionship of all the people that came from different backgrounds.

FEILER: While most of the group is drawn to the physical challenges of the journey, one member has been a practicing Buddhist for 30 years.

MARIANNE DRESSER: This pilgrimage I've been wanting to do since my 20s, before I even had become a Buddhist.

And then my life went on its way, and now 30 years later I'm able to do it.

FEILER: The group begins, like most pilgrims, at Temple 1.

John has enlisted pilgrimage historian David Moreton to explain the rituals at each temple.

MORETON: Everything starts at the front gate.

So usually the first step before you enter is to bow, just to say "I've arrived."

FEILER: Once inside, pilgrims purify themselves by washing their hands and mouths before announcing their arrival to Kobo Daishi by ringing the temple bell.

MORETON: You should not ring the bell when you leave.

That's considered bad luck, and all your wishes will go up in smoke.

So just ring when you arrive, then light a candle, light incense.

A lot of people have the name slips.

It's sort of like a business card.

You write your name, the date, your address, and some people write their wish, why they're making the pilgrimage, on the back.

FEILER: The ritual is the same in every temple, a familiar set of steps that brings comfort after the hard work involved in getting to each location.

The same prayers, or sutra, are recited in each place.

(chanting) The most popular is the Heart Sutra.

Among the best known of all Buddhist scriptures, it teaches that compassion comes only with the destruction of personal ego.

(chanting continues) (bells tinkling) Inside Temple 1, there's a shop where pilgrims buy clothes that identify them as henro, the name given to Shikoku pilgrims.

White is the color of death in Japan, and the tunic is like a burial shroud.

The conical hat symbolizes the coffin while also protecting the pilgrim from Shikoku's frequent rains.

Together the hat, tunic and other accessories reinforce the idea that the pilgrim is separating himself from everyday life.

There we go.

Okay.

So most pilgrims often buy a staff.

They believe that this is Kobo Daishi.

It's actually written here, "dougyou ninnen."

"We two walking together.

"” This character can mean "to go."

It also means "same practice."

So we're walking together, we're sharing the same practice.

Beautiful.

FEILER: The final essential is the nokyocho, or pilgrimage book.

At each temple, an attendant stamps and signs the book with exquisite calligraphy.

MORETON: This is actually the temple name.

That's beautiful.

So it's a little memoir that you've been to each temple.

FEILER: As John's group leaves Temple 1, they are less concerned with visiting every temple than walking to the ones they do visit.

DRESSER: Pilgrimage, you know, it even means walking, right?

It's wandering with a purpose, really, like you set out on a path, there is some goal, but it's everything that happens on the way is equally important to reaching the goal, I think.

FEILER: Kobo Daishi is venerated across Japan as the man who first made Buddhism accessible to the masses.

On Shikoku, many believe the Great Master, as he's called, walks beside every pilgrim along the trail.

It's one of the many beliefs that keeps his memory alive.

To learn more, I've come to the place where Kobo Daishi was born in 774 CE.

More than a million visitors a year come to Zentsu ji, the "birthplace temple."

(chanting) The morning service is always crowded with henro.

(chanting continues) The Buddha developed his path to enlightenment in India more than 2,500 years ago.

His teaching spread across Asia, reaching China and eventually Japan, around 500 CE.

Buddhism's core teaching focuses on the true nature of reality and says nothing is fixed, all actions have consequences, change is inevitable.

Before Kobo Daishi, Buddhism in Japan was an elite religion, focused mostly on the security of the state and the enlightenment of its highest officials.

Kobo Daishi's biggest change was to open the religion to everyone.

TRANSLATOR: Kobo Daishi wondered, why can't we all have the same chance of enlightenment?

Why can't we reach enlightenment in this life rather than waiting for the next?

The idea that anyone can be one with the Buddha, that's what Kobo Daishi thought Shingon Buddhism should be.

FEILER: A temple priest guides me to a statue of Kukai, Kobo Daishi's given name, when he was a young scholar monk.

In 804, when he was 30, Kukai made a dangerous sea crossing to China to study mystical Buddhist teachings that had been transmitted from teacher to student for hundreds of years.

So this is a great story.

So before Kobo Daishi went to China, he thought he might never see his parents again so he came to this pond and he wanted to give them a memento, so he looked into the water, saw his reflection and drew a self-portrait and gave it to his mom because this was a dangerous thing and he thought he might die for his cause.

That's the story he just shared.

Kobo Daishi returned from China and became the Japanese patriarch of a more populist and mystical form of Buddhism.

(speaking Japanese) TRANSLATOR: We think of human life as most important, but Kobo Daishi taught that plants and animals are just as precious.

We believe this in our hearts and it's Kobo Daishi who's responsible for that.

FEILER: Over time, this strand of Buddhism that began in China began to take on more and more qualities of Japanese life, especially its reverence for sacred mountains and other natural phenomena.

Like all religions, Buddhism adapted with each new country it went to.

When it arrived in Japan, it became infused with the Japanese love of nature from its traditional religion, Shintoism.

There's one expression of this that I love.

If you look at traditional Japanese paintings, those long scrolls of nature, there's usually a person contemplating the scene.

Nature and humans in conversation with each other.

It's the perfect emblem of the pilgrimage.

WILLIAMS: Taking the bus would be an easy way, but you get to see a lot more as you're walking, seeing the trees and the ocean and the mountains.

FEILER: Retired Marine Steve Williams has been walking the trail alone for a week.

He began at Temple 24, the Cape Temple, where he injured himself last year.

During the month he's on Shikoku, he hopes to walk 300 miles, ending at Temple 51.

WILLIAMS: The spiritual side of the trail is very personal.

It's different for everybody.

For me, I know God is inside, and on the trail I get more in touch with myself and I feel I just relate more to the spiritual side of myself as I'm walking and going to the temples.

(bell gongs) It kind of reinforces the whole meaning of the trail.

That's what it's all about is getting to know yourself.

It's a journey of learning about faith and what faith means to me.

FEILER: There are countless ways to make a pilgrimage these days.

You can do it by foot, you can do it by train, you can do it by taxi, you can do it by bicycle, you can do it by wheelchair, but for most people, the most popular way is to do it by bus.

Did you ever think about walking?

(speaking Japanese) TRANSLATOR: It's about physical strength.

I'm 75 years old.

I would love to walk, but with my health, it's not possible.

But those of us on this bus and those of us going on foot are on the same path.

Why have you come on this pilgrimage?

(speaking Japanese) TRANSLATOR: I've been working very hard and feeling a lot of stress.

My hope on this journey is to relax my heart and mind.

Being on pilgrimage is different from everyday life.

It's like stepping into another world and creating a better incarnation of myself.

(speaking Japanese) TRANSLATOR: Every time I come, it's new.

The energy in the air feels different each time.

And this time, I feel it's not me that's moving, but the gods pushing me along.

FEILER: One attraction of this pilgrimage path, like many around the world, is that it never closes and it never changes.

It's an open invitation for pilgrims to come at whatever stage of life they're in.

And a surprising number of people come year after year, using the stability of the route to mark their own evolution.

MORETON: With the paper slips, there's different colors of them.

Those who have done it one to four times, the pilgrimage, they use white.

Okay, so we have here all of the different colors.

So the gold is the highest?

This is for over 50.

And when you get over 100, it's cloth.

However, some people are very humble, so no matter how many times they've done the pilgrimage, they always want to stick with the white.

So this fellow, he's done it 142 times.

So this 142 means he has been to this temple, or the entire pilgrimage 142 times?

He's completed the whole circuit 142 times.

FEILER: 700 miles.

142 times.

That's almost 100,000 miles!

Even if you drive, that's years of travel.

How many times have you made this pilgrimage?

MAN: Nana.

FEILER: Seven?

TRANSLATOR: I feel that Kobo Daishi plants something inside of me, like a calling to keep coming back.

There's just a cut.

You can see actually the next temple on the far peak over there.

Taking the bus definitely has its advantages.

For anyone walking to this temple, it's a tough four-mile slog up the back side of the mountain.

When you travel by bus, you can see a huge amount of terrain in a very short period.

You can be in a crowded city, you can be alongside a rice paddy.

And here we are at one of the highest spots on the island, at the Temple of the Great Dragon, where I discover it was our guide who'd made the trip so many times.

(chanting) You have made this journey how many times?

(translated): 142 times.

Have you ever walked the entire route?

Yes, the first 120 times I went by car, but when I turned 60, I decided to walk it.

So this time you're leading a group.

What message do you want the group to take away from ts experience?

I hope they remember their thoughts and feelings and share these when they go home.

FEILER: John Osaki's group came to hike and now they begin the toughest and steepest ascent on the trail, 2,000 feet straight up the side of a mountain to the Peak Temple.

On the climb, they fall in with a party of Japanese henro walking the entire trail.

This is one of the most meaningful times in any pilgrimage, when people from different cultures, speaking different languages, often worshipping different gods, find camaraderie.

There's a kinship of the traveler, as pilgrims create their own wandering congregations.

For centuries, pilgrims have been placing carved stones, notes of encouragement to fellow travelers and poems along the trail.

LINDA HAMILTON: I love these signs that are on the way.

They always keep you on track.

You always know where you're going.

You never feel lost.

DRESSER: Kobo and all of the statues along the way, they're all my friends and all the bodhisattvas.

It's like seeing old friends; it's like going to visit an old friend.

This one is very peaceful and serene.

This is Jizo.

Protector of children?

Right, and travelers.

So one of the bodhisattvas.

So they can live thousands of years?

They take a vow that they'll help other living beings.

And not go on to the afterworld?

Even though they could.

Right, okay.

(breathing heavily) FEILER: While people have walked in Kobo Daishi's footsteps for more than a millennium, the pilgrimage assumed its current form by the 1600s.

A number of independent Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines joined together to create a single route.

The first guidebook was written in 1687.

Travel has always been difficult.

Thousands have died en route over the years.

This is a 200-year-old henro grave.

I'm sure he's been prayed for many, many times as the henro go by, so his soul is free.

And what a beautiful place to be.

FEILER: Now that the group has been hiking for several days, a change is occurring.

They talk less about the physical challenges of their journey and more about their inner beliefs.

HAMILTON: I'm not a Buddhist, but I admire the principles.

It's a way of life, a way of thinking, a way of speaking, a way of being.

INGRID LOH: The pilgrimage really allows you to be who you are and think about everything that makes up who you are and how you want to use it in the big scheme of things.

(applause) (laughing and cheering) (bell gongs) (chanting) FEILER: It's the eighth day on the road for medical students Jenn Tsai and Alex Fu.

They've walked almost 100 miles, just over ten percent of the entire route.

TSAI: It feels like we've been traveling forever.

Starting to get used to really, the grind.

Right, right, we're getting used to the fact that we're walking 20 kilometers a day.

At the end of the day my feet always hurt.

It feels like 100 boxers had... (laughs) pummeled my feet.

I don't think it hurts that much less now, I've just gotten used to it.

We just sort of expect that it's going to happen.

It's just going to happen.

Right.

TSAI: I think for me it's definitely a spiritual journey.

I don't practice any religion actively, but I' always had spiritual beliefs.

(bell gongs) I think you don't necessarily have to believe in a certain religion or believe in every aspect of a religion literally in order to take on some of the feeling and meaning.

(chanting) I can't say I'm a practicing Shingon Buddhist.

I don't know necessarily that I would literally believe everything that we say or do at the temples, but I think the spirit of that is what counts and going through those actions.

And especially seeing also how important they are to other people, I can take on some of that meaning for myself.

FEILER: Pilgrimage may be a spiritual act, but the body needs nourishment, too.

In the middle of nowhere there will be vending machines.

Yes.

So I feel like you never have to worry about getting dehydrated in Japan.

FEILER: Food can be bought at convenience stores in every small town.

But there's a wonderful tradition of giving sustenance to the pilgrims, called osettai.

Local residents used to do this only for monks, but now they show this respect to all pilgrims, offering food, drink, sometimes even money.

It's a way for islanders to give and receive blessings from the pilgrimage.

TSAI: There are times when we start wondering, why are we even doing this?

Is it worth it?

And then there's been so many instances where people are really kind to us.

They give us things, they give us the encouragement, the advice that we need and then it feels worth it again.

So what do you think we're going to do about lodging for the night?

It's getting kind of cold.

So actually if we can find a spot near the beach to set up camp.

Where?

It looks like there's some toilets around here.

FU: It's kind of interesting.

You know, we come into this trip, one of our main goals is to make this kind of a spiritual journey, self-reflection, and a lot of our time so far has been really trying to get used to the practical aspects, find places to stay, find food, shelter, rather than the sort of ascetic solitude that you think about when you think of Buddhism.

We're going to be facing that way, right?

I wanted to face this way.

You want to face this way, okay.

TSAI: We're getting along really well.

We've been together for about three years.

FU: We don't see each other 24 hours a day because we're doing two different specialties, so during the daytime we usually don't see each other.

I think it's a good test.

If we get along all the time, seeing each other straight for 40 days.

Don't put any more tension on it.

Okay.

TSAI: So far, so good.

We have our differences of opinion.

(laughing): We do.

But I think two minds are better than one sometimes.

Don't undo that.

FU: It's a good time to realize how much we're able to compromise with each other.

So far we're not ending the trip so I think that's success right there.

And I definitely do think that this trip can only really deepen the connection.

It's really that sort of trip.

TSAI: This is a really nice view.

Go to sleep with the sound of the waves.

You don't get to do that every day.

FEILER: I have to say I was not exactly prepared for the scope of this thing.

It is massive.

One thing is to see it laid out on a map, but when you're walking, it can take three or four days to get between some temples.

Or you get to where the temple is on the map, and you got to climb five hours to get to the top.

We're actually driving, but it takes us a very long time, sometimes three or four hours just to get from one place to the next.

If you are walking on this pilgrimage, you earn those stamps in those books.

Countless legends surround Kobo Daishi, but there are places where it's possible to catch a glimpse of Kukai, the man, rather than Kobo Daishi, the legend.

Along the southern coast is a cave where many pilgrims stop to pay homage.

Sometime around 796, when Kukai was in his early 20s, it's believed he lived here for a while.

In this remote, forbidding place he first found enlightenment and dedicated his life to serving others.

In many religious stories, maybe all religious stories, there's a moment where the hero leaves the civilized world and goes into isolation.

That happened with Moses in the Sinai, with Jesus in the desert, with Muhammad, with the Buddha and also with Kobo Daishi.

And then while in that separate state, the hero has some insight that he brings back to the civilized world.

Part of the knowledge Kobo Daishi brought back from China is on display in a temple high above the cave, atop a nearby mountain.

Many of these temples have stairs and I struggle with them because I have a leg injury.

But it shows you that no matter how you get here, you still have to exert.

Suffering is part of this journey and part of all sacred journeys.

As long as humans have walked, they've walked to get closer to their gods.

In the early ninth century, after returning from China, Kobo Daishi was the acknowledged leader of mystical Buddhism in Japan.

Dividing his time between Shikoku and the mainland, he trained disciples here at the Vajra Peak Temple.

The chief priest offered to show me the master's ritual instruments and sutra scrolls.

You're saying he actually used this for a ceremony?

TRANSLATOR: Everything inside this case was used by Kobo Daishi.

He carried them on his shoulders and used them for rituals.

So he carried it from place to place or just within a temple on his way to perform a ceremony?

There were few proper temples so he carried the ritual instruments on his back from place to place.

This is one of the two major sutras Kobo Daishi himself brought back from China.

FEILER: He was living in China and he inherited this whole tradition, so this was the wisdom that he brought back from China?

During his lifetime, his disciples copied it from the scrolls he brought back to Japan.

The scrolls are in Chinese, exactly how they were taught to Kobo Daishi.

FEILER: This is one of the most sacred and profound of all Shingon scriptures, similar to the Heart Sutra that pilgrims chant at every temple.

It describes how all things are connected and change is inevitable.

CHIKU SAKAI (translated): And people still come here to find and renew their faith.

This temple is a place of knowledge where Kobo Daishi changed people's lives.

OSAKI: A little bit of advice, and a small word of warning.

FEILER: The hiking group's objective today is Shosanji, the Burning Mountain Temple.

It's one of these roller-coaster hikes, goes up and down, up and down.

So that gives you a cumulative elevation gain of 3,500 feet up, 1,500 feet down.

The steepest section probably is the last pitch up to Temple 12, which is one of the places they call the Henro Korogashi, place where the henro falls down.

DRESSER: How's that trail go again?

It goes up, down, up, down and up again?

OSAKI: You got it.

(laughter) Okay.

Ikimashou.

It's slippery.

OSAKI: So Shikoku's mountains are not as high or rugged as other places in Japan, but there's this other element, great spiritual element of pilgrimage, which in and of itself makes hiking in the mountains here special.

Look at that.

The pink cloud of sakura.

Sakura snow.

It's beautiful.

WOMAN: It's all nature.

That's spiritual.

The whole story of this pilgrimage too is, you know, Kobo Daishi studied in temple in the national capital, but eventually decided to spend part of his time in the mountains meditating, and that was sort of an important piece of who he became because he spent half the time here.

We started it was 16 kilometers.

So we walked 20 minutes for .7 kilometers Oh, that's pretty slow.

That's all right.

We're not on a time schedule, right?

No, absolutely not.

FEILER: Even in spring, it can snow at this altitude.

Bad weather, along with the other routine hassles of travel, can force pilgrims to face their own limitations, confront their discomfort.

And sometimes that discomfort comes from a world away.

Chris and his wife just received word that his sister suffered a stroke and is in critical condition.

LOH: We started as just a hiking trip, and it is some kind of pilgrimage, we didn't realize it.

On this route we are trying to wish her good health every turn that we could make.

So it took on a new meaning.

FEILER: The driving rain demands concentration at every step.

But such deep focus on the present sometimes frees up the mind.

DRESSER: The great thing about hiking, especially if you get past the first hour or so when you're just like, "Ow, why am I doing this?"

is you're just moving through space, it's just your body's sensations.

You have to pay attention, especially in tough conditions.

It's easy to fall, something could happen.

It really cuts off all the extraneous noise of the mind, and I really like it because at some point, I stop being someone who is walking and I am just walking.

TOM FLICKINGER: It was a slog, in a monsoon.

That last part was...

I hit the wall.

I'm going to have to take a rest here.

I'm glad I had my Kobo Daishi stick, though, because without this, I don't know.

There were several places where I really needed to lean on it just to get my footing.

DRESSER: All along the way is Kobo Daishi statues and people's graves.

All along the way are markers.

So you really do feel that Kobo Daishi is there with you.

HAMILTON: I felt like Kobo Daishi was right there with me.

The wind was whipping around, but I felt like I was very protected, and I just understand how he loved the beauty of nature.

It's what brings you close to the meaning of life is this incredible beauty that surrounds you.

Whether it's raining or whether it's sunshine, it's still as beautiful one or the other.

(bell gongs) (group chanting) DRESSER: I'm soaked to the bone.

I'm sore in my hips and my knees and my feet.

I was lashed by the wind and brushed by the rain and slapped with tree branches, and I really feel that the natural world is just interacting with me in a very vigorous way today, and it's been magnificent.

I wouldn't have missed it for anything.

Itadakimashita.

WILLIAMS: It can get pretty lonesome if you're walking by yourself.

I try not to think about it, just think about keeping going.

I think about my family and think about my wife and know that she's there for me.

Right now I'm having problems with my leg and walking with the blisters, walking on the side trying to avoid the blister and avoid the pain, but then you are walking awkwardly and that just creates more problems.

My usual pace is around 22 kilometers, but I was walking with some Japanese friends, they wanted to go 27.

I went along with them and kind of overextended myself.

I tried to keep up with them, but it was just too much.

FEILER: Outside the gates of Temple 45, Steve Williams checks into one of the many henro inns dotted along the trail.

Steve's henro staff is treated with special reverence as it embodies the essence of Kobo Daishi.

Wash the staff and you are said to wash the feet of the master.

Steve still has a long way to go to reach his goal of 300 miles.

He wonders if he's going to make it.

WILLIAMS: You get up at 7:00 in the morning and start out the door and you keep going until 4:00 or 5:00 in the afternoon.

And it can wear you down day by day.

The thoughts come up that I can just give up and go home, but then I get another thought, thinking, no, you've got to keep going.

All day long it's a fight to keep motivated and keep walking.

FEILER: Jenn and Alex have walked another 80 miles, but their pace is slowing and now they must confront a harsh reality.

TSAI: At the beginning of this trip, we had really been hoping to finish it all in one go.

We had 38 days to do that, which is a bit short because the average is about 45 days.

We had this sort of idealistic hope that, you know, we would sort of get into and start walking real fast and catch up.

And a couple of days ago we sat down and thought about this, and realistically it's just not going to happen.

We had to think about sort of what our priorities were, whether that was to really just push ahead, or to accept the fact that we weren't going to finish.

And then we opted for the latter.

FU: Really what was the point of us doing this journey in the first place, right?

Right, we had picked walking because it's the whole process of, you know, really taking the time to meet all the different people, and see all the scenery, you know, one step at a time.

FU: Appreciate the journey that many people have taken in the past.

And if we'd just rushed on to each temple, it would just end up being this grueling relay that we just didn't want to turn into that kind of thing.

FEILER: No matter the pilgrimage, no matter the faith, every traveler reaches the same point: when the inward journey starts to become more important than the outward one.

(priest chanting) Jenn and Alex, who still have several weeks ahead of them, attend the most potent of all mystical Buddhist traditions, a traditional fire ceremony or Goma.

(chanting) This tradition dates back to ancient India before the time of the Buddha.

(chanting continues) The Goma is a spiritual and psychological cleansing in which participants ask deities to purge them of negative thoughts and desires.

(chanting continues) Every wooden stick consumed by the flames carries a wish or prayer.

(chanting continues) TSAI: We're really lucky that we're able to be a part of this ceremony.

Maybe Kobo Daishi's really watching over us that we were able to be blessed this way.

(chanting continues) FU: I'm not sure quite how to describe what just happened.

Just watching the flame and listening to the chants really made me feel a sense of peace, oneness.

(chanting continues) But it's really hard to explain in words what that was like.

TSAI: I think this might lighten the load for us for the rest of the journey, to be able to unload some of the thoughts and the feelings and expectations that we've had so far.

We can go on and really just experience what comes next.

FU: I really do think that if we come across tough times during our training in the next few years, and seeing very sick patients, what we went through on this trip will serve as a standard for setting our perspective on how we should deal with things, how we can step back, take a look at the bigger picture.

Hopefully that will be very helpful to us in how we carry ourselves for the rest of our lives.

FEILER: By the time I meet Steve Williams at a guesthouse about three-quarters of the way around the island, he's been on the road for more than a month.

So here we are now at a critical moment.

Are you going to keep going or are you going to stop?

WILLIAMS: I'm going to stop now and come back in October.

I'm going to do everything differently.

My whole outlook has changed.

I was goal-oriented and you think about... Well, you have to get to this temple, and you have to get there on time, have to walk so many kilometers.

I'm not going to do that anymore.

I'm just going to go at my pace and take my time and enjoy it more than just trying to get through the whole thing.

That's a pretty powerful lesson to come from a journey like that.

It makes me happier to do it this way.

I was miserable before.

I'd go through the motions, I'd go to the temples, I'm rushing through it and I didn't take the time to really experience it and just kind of absorb it in.

And this last few days from 37, things kind of slowed down for me.

At the beginning I felt bad by taking transportation, by not walking.

I could see other henros walking and I'd go, "Oh..." I felt really bad.

But then I met people on the train and the buses that I would never have met and it opened up a whole new area of meeting people.

What a beautiful story.

FEILER: John Osaki and his group have reached the same point on the trail, so Steve and I join them for dinner.

(laughs) And everyone shares stories from the road.

WILLIAMS: Many religions are very secular, and you're not accepted and things like that.

I find the same thing.

But you just become part of their experience and they accept you totally.

They're so happy.

Happy.

When you say ganbatte.

I was at a temple and this little old lady came up to me and she pointed at my shoe.

She said abunai, "dangerous."

My shoe lace was untied and she reached down and tied my shoelace, like I was her son.

That is so kind.

I was really touched.

When you are walking from temple to temple, when you're putting one foot in front of the other, what are you thinking about?

I think about all the centuries before, of all the people in whose footsteps I'm following, seeing the places where other henro did not make it.

The idea of a pilgrimage when you set a goal to get from one temple to the next becomes a reason to continue when it may be difficult, or when the rain is pouring down on you when you figure you could just bail out at this point in time, but you keep going.

I started out as a hiking trip, but I also felt, because my sister got sick the second day I was here-- my nephew emailed me-- then we start thinking that maybe this trip do have a meaning to me.

He did sign those cards every day and pray for her.

And she did get better.

My nephew had a second email and said that she is 60% better.

FEILER: Do you feel you played a part in that?

I don't know, I'm a doctor myself, I'm a scientist, but of course whatever comes.

As a wish come true, of course I'd be very happy.

FEILER: If I might, it seems to me that your head and your heart are fighting.

Your head wants to say it didn't happen because of the pilgrimage, and your heart is saying... maybe.

Don't we always think about religion that way?

Do things happen just by random or do we come out of some goodness or some plan?

This type of insight that you've all said you get when you walk on this path in this place, is that transferable back home when you're not here?

WILLIAMS: You become permanently changed, because we spend our lives as human doings and we work for the company all our lives.

And now we take the time out for ourselves, where in the Western world we don't do that.

And in this way we can take ourselves out of that and find out what we really believe, not just what's accepted by our cultures.

Find out what we believe personally and that's what I found on the trail.

FEILER: After ten days on the trail, John Osaki's group arrives at a steep mountain path.

It leads to Temple 88, the final leg of their journey.

For all who reach here, the sense of completion is palpable.

Temple 88 is known as Kechigan-sho, "the place of fulfilling your vow."

(speaking Japanese) FEILER: And that feeling of fulfillment, of achieving your dream, can be overwhelming.

(chanting) Everybody really hung together.

I mean they kept right up, it was a tight group.

OSAKI: Especially today, we were very cohesive, I think.

I mean it was a really nice way to finish because everybody was together.

FEILER: One reason pilgrimages continue to have such appeal is that they combine spiritual journeys with physical ones.

The exertion of the travel enhances and intensifies the emotion of the religious quest.

(chanting) DRESSER: I'm really glad that I just tasted a bit of the pilgrimage, and I definitely would like to do the whole thing.

It may take me several visits to Japan, but it kind of gets in your blood.

(speaking Japanese) OSAKI: A lot of us feel this pull.

Like I want to come back and I want to do all of them now.

FEILER: The journey, in other words, continues.

It's the perfect metaphor for Shikoku, where many pilgrims traveling the path don't stop at Temple 88.

Instead they go back to Temple 1 and make the circle complete.

They say the final visit here is for thanksgiving, expressing gratitude for arriving safely.

But it's a reminder that the journey ends where it began.

There is no final point.

And maybe that is the point.

For most pilgrims, the journey is not the destination, the destination is some new personal place.

And in Shikoku, that can't happen until once again you leave Temple 1 and this time, head home.

FEILER: It's been called the birthplace of humanity.

Jerusalem, holy to Jews, Christians and Muslims-- half the world's believers.

This city has been built, sacked, rebuilt and wept over dozens of times in the last 3,000 years.

It's a city of conflict and coexistence.

Jerusalem, next time on Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler.

Find more information and exclusive video on Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler at pbs.org/sacredjourneys.

Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler is available on Blu-ray and DVD.

To order, visit shoppbs.org or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

The Evolution of Buddhism in Japan (Shikoku)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 3m 38s | Video resource from PBS LearningMedia. (3m 38s)

Notes from the Field: Abalone (Shikoku)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 2m 9s | Taste the Shikoku delicacy of abalone. (2m 9s)

Notes from the Field: Jenn and Alex (Shikoku)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 2m 40s | Meet American pilgrims Jenn and Alex journeying around the island of Shikoku in Japan. (2m 40s)

Notes from the Field: Osettai (Shikoku)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 3m 17s | Take a break with Shikoku locals. (3m 17s)

Notes from the Field: Steve's Story (Shikoku)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 2m 39s | Meet American pilgrim Steve Williams traveling in Shikoku, Japan. (2m 39s)

Notes from the Field: Temple of the Two Dragons (Shikoku)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 3m 15s | Travel to the Temple of the Two Dragons on the island of Shikoku. (3m 15s)

Notes from the Field: The Henro (Shikoku)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep2 | 2m 27s | Take a look at the traditional garb of the henro, the pilgrim of Shikoku. (2m 27s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Ep2 | 1m 34s | Travel with American pilgrims to Shikoku. (1m 34s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler provided by Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Hans and Margret Rey/Curious George Fund, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by public television viewers.