State of the Arts

State of the Arts: December 2025

Season 44 Episode 3 | 27m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, The Trenton Community A-Team, and Oh God...Beautiful Machine

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey mounts a fresh take on Mary Shelley's iconic story, adding to the long legacy of Frankenstein. The artists of the Trenton Community A-Team connect at the Trenton Area Soup Kitchen. And renowned poet Yusef Komunyakaa and composer Vince di Mura’s genre-bending symphonic work, Oh God...Beautiful Machine, debuts with The Capital Philharmonic of New Jersey.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

State of the Arts is a local public television program presented by NJ PBS

State of the Arts

State of the Arts: December 2025

Season 44 Episode 3 | 27m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey mounts a fresh take on Mary Shelley's iconic story, adding to the long legacy of Frankenstein. The artists of the Trenton Community A-Team connect at the Trenton Area Soup Kitchen. And renowned poet Yusef Komunyakaa and composer Vince di Mura’s genre-bending symphonic work, Oh God...Beautiful Machine, debuts with The Capital Philharmonic of New Jersey.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch State of the Arts

State of the Arts is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipNarrator: The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey brings us a new take on Frankenstein's monster.

Was he simply misunderstood?

The Creature: See what a wretched outcast I am?

I am similar to them.

Mary Shelley: But also strangely unlike them.

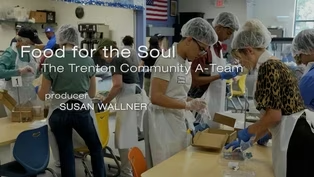

Narrator: The artists of the Trenton Community A-Team first met at the Trenton Area Soup Kitchen.

More than 25 years later, the group continues to thrive.

Chessman: This place has a soul.

It is a space that looks past the need of the person, and instead it nourishes that person.

Narrator: And a monumental new collaboration by poet Yusef Komunyakaa and his friend, composer Vince di Mura.

Komunyakaa: I think of language as music.

Poetry, in a certain sense, invites us in as participants.

But the music brings it all together.

di Mura: Because there's music in the poetry.

Both: [ Singing ] Speaking to the world.

Narrator: "State of the Arts'" going on location with the most creative people in New Jersey.

Announcer: The New Jersey State Council on the Arts, encouraging excellence and engagement in the arts since 1966, is proud to co-produce State of the Arts with Stockton University.

Additional support is provided by the Pheasant Hill Foundation, Philip E. Lian & Joan L. Mueller, in memory of Judith McCartin Scheide and these friends of "State of the Arts."

[ Orchestra playing ] [ Choir harmonizing ] Woman: [ Singing ] Oh God.

What a beautiful machine.

Man: [ Singing ] Machine.

Woman: All this breathing ivory.

Both: [ Singing ] Speaking to the world.

Oh, God.

di Mura: [ Singing ] What a beautiful machine.

[ Normal voice ] You know, this beautiful, soulful female voice, right?

The simple choice would have been, you know, let's make it pretty.

Komunyakaa: Toss off.

di Mura: Right.

Komunyakaa: Yeah, but it isn't.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I think of language as music.

Poetry, in a certain sense, invites us in as participants, but the music brings it all together.

di Mura: Because there's music in the poetry.

Komunyakaa: Yeah.

That's why, as I'm writing, I'm usually saying everything aloud as well.

Oh, God, what a beautiful machine.

All this breathing ivory speaking to the world.

Narrator: Yusef Komunyakaa is a renowned poet whose work draws deeply from his childhood in Louisiana and his time serving in the Vietnam War.

His celebrated collection of poetry, "Neon Vernacular", earned him the Pulitzer Prize in 1994. di Mura: I'll never forget the first time I met him, because he came walking in the door with a copy of "Neon Vernacular", and having never met me, signed it and invited me to the house for dinner.

But that's the kind of person he is.

Narrator: Vince di Mura is a composer in residence at Princeton University.

His collaborations with Yusef Komunyakaa have spanned decades.

[ Keyboard playing ] "Oh God...Beautiful Machine", their fourth collaboration, is a symphonic pairing of music and language.

di Mura: Watch this.

[ Singing ] There was a time we could sing of springtime.

Both: [ Laugh ] di Mura: [ Singing ] As if we ever will run out of choices.

Komunyakaa: [ Singing ] So we will never run out of choices.

di Mura: [ Normal voice ] Right.

Komunyakaa: [ Normal voice ] The journey begins with a question.

Larry Hilton, who's given so much to the community, he asked me, he said would I be willing to write a lyric that dealt with climate change?

Narrator: The late Larry Hilton, beloved patron of the arts and champion of Trenton's cultural community, asked his friends to create a big new piece focusing on climate change and the human experience.

Yusef and Vince eagerly agreed.

They created a work that brings together poetry, jazz, blues, samba, gospel, and even one movement featuring Chinese music and language.

Woman: [ Singing in Chinese ] Narrator: "Oh God...Beautiful Machine" then found its home with the Capital Philharmonic of New Jersey.

Grand: I think the Capital Philharmonic has always had an incredible tradition of supporting projects that are a little bit unusual.

It's going to have the real feel of a festival and the real feel of the city of Trenton coming together to put something that represents us.

di Mura: In some ways, it's like Larry's last gift to Trenton.

Komunyakaa: Mmm.

di Mura: Larry wanted this to be a big, major composition.

[ Orchestra playing ] Komunyakaa: It's naturally about nature and man reacting against this great apparatus out there.

Nature we don't think of as a machine, and yet all the pieces fall together as this great, mysterious moment.

[ Orchestra continues playing ] I was already there in the midst of climate change.

Growing up in Louisiana, I would go out into the vegetation and receive, in a way, the surprises that nature had for me.

There are the birds and butterflies and all that, but also the snakes, you know.

di Mura: [ Laughs ] Chimes.

[ Note plays ] Strings.

[ Note plays ] I had to listen to recordings of him reciting his work to understand how to phrase it musically.

Komunyakaa: When wind sang through the grass... di Mura: [ Singing lyrics ] of men and angry wills... [ Singing ] A million hooves of buffalo thundered over Oklahoma hills.

[ Indistinct chatter ] di Mura: Hi, everybody.

Just a word about "Buffalo Grass".

This was the first poem that Yusef gave me, and it was inspired by the fact that he saw in a magazine a picture from the 1880's of the destruction of the buffalo, that there were these mounds of skulls.

And he wrote this as a metaphor for the carelessness of how we treat nature.

Grand: Let's try from the beginning of "Buffalo Grass".

[ Drums softly booming ] [ Orchestra joins ] It's always interesting when people show up to the first rehearsal and have never seen the piece before, and everyone is hearing it for the first time.

It's a really special occasion.

But I've been in contact with Vince for many months as he's been completing this.

It's got that feel of marriage, of text and music.

[ Music plays ] Woman: [ Singing ] Komunyakaa: Sometimes the piece start breathing.

di Mura: Yeah.

Komunyakaa: It's alive.

di Mura: Oh, absolutely.

Komunyakaa: And what happens is that there's that push and pull.

That was the most exciting thing for me about it.

di Mura: I learned so much from Yusef's work, but I also learned so much from him, you know.

Komunyakaa: And I've learned from you as well.

di Mura: Yeah.

Komunyakaa: So it's been a shared voyage.

di Mura: Right.

Komunyakaa: The soul inside of his music presented a certain kind of humanity that brought everything together.

di Mura: I don't want to play with anybody else.

His work has spoken to me from the first day I read it.

Narrator: An audience filled the Patriots Theater at the War Memorial in Trenton for the 90 minute symphonic work on humanity's impact on this planet, an evening where two art forms, poetry and music, came together as one beat.

Woman: [ Singing ] [ Chorus joins ] [ Music continues ] [ Laughing together ] [ Audience applauds ] [ Gentle piano plays ] Narrator: Up next, art as food for the soul at the Trenton Area Soup Kitchen.

[ Piano continues ] Catanese: I love TASK and I love everything the soup kitchen does there.

It's very welcoming.

The soup kitchen makes everybody feel welcome.

Kisela: We were going to the soup kitchen.

They said there's an art group.

So I joined the art group and I've been going there ever since.

I've been doing seascapes 'cause I like the ocean.

I just like being out there amongst the people, amongst the seagulls, listen to the ocean waves.

Lettieri: Art is, in my opinion, so deeply ingrained in what it means to be human.

Whether it's music, whether it's writing, whether it's painting.

It's a beautiful thing, and I'm happy to be here.

Chessman: I didn't want to come down here because I had no idea what a soup kitchen was.

I just had in my head, like the Great Depression, everybody's standing up in the food court or something.

But then somebody said, "Nah, man, they got music.

They have art.

They have -- they have all these programs."

So I went down here and I was blown away.

It's kind of a recurring theme.

I was telling Frank about that.

It's like a dark forest with a path or a stairway or something that leads into mystery.

It's kind of like me coming out of the darkness, wanting to go toward the light.

Carol: I wanted to be an artist.

I wanted to go to art school.

and my mother said there was no money in the art, that she wanted me to be a hairdresser.

I think first, then draw it, and then paint it.

That was my dream, to be an artist.

Catanese: First, we give them a place to feel safe and to create their art.

We don't tell them how to make the art or what to do.

It's more, here's your blank canvas.

I want to see what's coming out from inside you.

Now, if they have questions technically like how do I make this happen?

More than happy to be there and help them out with that.

But mostly I want to get what they have inside out to the world.

Gary: We're going to go back a few years, you know, end up getting displaced.

So I was sleeping in my car for a while, right?

I had a job, I lost my job, and I was drawing every day.

Draw, draw, draw.

And, um, like, all, all the, like, the negative bad things just kind of went away.

Even during times, people -- A guy told me, he said, "Yo, you need to stop wasting your time drawing."

I'm like, [scoffs] "whatever, yo."

I just kept drawing and drawing and getting better and better and yeah, that's how I ended up with the A-Team, you know?

But I called myself Solo, though, because during all that time my mother passed away.

She passed away about two years ago.

I have a lot of friends that passed away.

My nephew passed away.

Uh, he was 22.

I loved that boy like a brother.

Loved him like a son, you know?

My dad's gone.

If we were a platoon, if I was platoon, I'm the last soldier standing.

And that's why I call myself Solo.

[ Music plays ] Catanese: So this is Studio 51.

It's an old carriage house from the 1800s that they converted into an art studio.

And really, this is because at Soup Kitchen, we have the one day art program, and sometimes that's just not enough.

You know, you really want, if the artists are excited, they want to do something.

So TCAT, once they became a non-profit, got this building, and they converted it into a two story art studio, and we provide them with all the materials they need, all the canvases, paints, anything like that.

We have Art All Day event here, which is a city-wide event where there is a trolley that goes around all the different art studios and art exhibits.

Rainbow: I started showing with the A-Team and working with them like maybe in the early 2000s.

But you know, I really think it's important, you know, for everyday people to have access to art.

And really, you know, I think there's something powerful in doing art for art's sake and really doing art as a healing practice.

You know what I mean?

Kisela: "Leaves were falling all around.

I like fall..." Rainbow: I've seen a lot of people come through the A-Team and really develop their own unique styles and really take it to the next level.

Man: It is so original and it captivated my eye.

I believe Charles did a fantastic job making this painting.

I'm happy to get this one for my collection.

Smith: My name is Charles Smith, and I'm working on, like, a world.

It's like a creation about the world, the ships and stuff.

Like a future vision of this world.

You know, it was like a puzzle to me at the first time I was doing it, you know.

Then I learned how to do it, and it comes out nice.

Catanese: The reason I love doing this is seeing their art up on the walls and seeing people react to it.

Beatty: Thank you for having us.

Thank you.

Catanese: I think it's a super boost.

Every time we have an exhibit or something, the next art program, next week everybody's super productive and excited and ready to get more art out there so people can experience their lives through their art.

Beatty: I love painting, making things, creating, making people smile.

I've been here since the '90s, like 1990.

Me, Shorty, we've been here since then.

Catanese: Trenton Community A-Team is the artists.

They started this.

Now, Herman "Shorty" Rose, he was one of the founding members of Trenton Community A-Team.

He started doing art and I guess his art, again, as art does, was drawing people in.

[ Hip-hop plays ] Lewis: When I first started going to the soup kitchen, it was to get meals.

Because during that time I was going through a little struggle in my life, and then I just joined the art team and it became a passion.

Once I got in there and realized that I don't have to do art to please other people.

Whatever I put down, that's my art and my vision.

Frails: I volunteered with the church, going to the soup kitchen, and I fell in love with the soup kitchen.

Then later on, I found out it was an art class.

Oh, what a blessing.

So that got me into my art.

And I just -- just a joy to be around the artists.

It's something that seems to be about these people, you know?

We connect.

They're lovely people.

Chessman: This place has a soul.

It is a space that looks past the need of the person and instead it nourishes that person.

Narrator: Every generation has their Frankenstein.

Who is ours?

Last up, a new production of the classic.

Narrator: Every generation has its Frankenstein.

And every Frankenstein reveals something about its generation.

It is, after all, a tale of the creator and the creation.

Frankenstein's creature is a little like the Mona Lisa.

He's everywhere and shape-shifts into whatever people need him to be.

But the basic elements are almost always the same.

His green skin, square head, and bolts coming out of his neck.

The grunting, the lumbering gait and, well, not much beyond that.

Colbert: We don't really know know you.

[ Laughter ] Narrator: A recent stage adaptation at the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey is making the case that the monster Mary Shelley introduced to us over two centuries ago is very different from the one we've gotten used to.

Crowe: One of the things with Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" that keeps coming back over and over again is the humanity of the monster.

This character has a brilliant mind that, in the course of a year, teaches himself to speak and to read and reads "Paradise Lost" and the Bible and Shakespeare.

Singh: But then, ironically, you have James Whale's 1931 cinematic version, which removes so much of the humanity.

Salam: A blockbuster movie that reached pretty much every human on the planet.

It can be very loosely interpreted.

Narrator: So what happened in the last century of Frankenstein adaptations?

And did a small theater in New Jersey finally get it right?

[ Music plays ] Dr.

Frankenstein: In that unmapped region, my foot, my heart, and my eyes may now finally fall.

Break boundaries.

Cracks.

[ Crash of thunder ] Let light in, let night out.

Banish darkness.

Begone!

Let light and life flood forth and darkness drown!

[ Storm rumbling ] [ Dramatic music plays ] [ Tense music plays ] I now understood things that only God had known.

I had only to put that understanding into practice, into being.

Narrator: At the heart of every version is a scientist with the ambition to play God.

Mary Shelley's warning against the blind hubris in all of us is perhaps Frankenstein's most enduring trope.

Nathan: You know how I cracked it?

Caleb: I don't know how you did any of this.

Dr.

Frank-N-Furter: [ Singing ] If he only knew of my plan!

In just seven days, I can make you a ma-a-a-a-an!

Dr: Frankenstein: I know what it feels like to be God!

[ Storm rumbling ] [ Tense music plays ] Narrator: Mary Shelley does not describe the moment of animation in great detail, but no scene has been more palpably exciting to the imagination of filmmakers, who themselves create life where there was none.

This defining moment when the scientist crosses the threshold from sanity into madness, from man into monster, has enraptured us for generations.

We know it's wrong, but we can't look away.

Dr.

Frankenstein: It's alive!

It's alive!

Dr.

Frankenstein: It's alive.

[ Blasts and crashes ] [ Tense music plays ] [ Electric crackling ] Dr.

Frankenstein: O, God!

Do I mock you?

I reject you.

I-I reject you!

Salam: When you put a Frankenstein monster on screen, you want the monster.

The monster is the part that is so fun to explore visually.

Yunger: Holy ugly!

Who's the lumbering sad sack?

Dr.

Frankenstein: That's my creation.

He's kind of a pain in the ***.

[ Dramatic music plays ] Narrator: Lately, though, something's been happening with our monsters.

Singh: Monsters have gone from menacing to misunderstood.

Where they've gone from beings whose monstrosity is grounds for their capacity to evoke fear, to monstrosity as a grounds for empathy.

Giulia: Help!

Don't hurt us!

Singh: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein really predates the big explosion that you find right now.

Crowe: When designing the creature, we wanted something that allowed for great movement, and we wanted to make sure that we were not losing the ability for the actor to be expressive physically and facially.

A sense of soul, of life, of something beyond the monstrous to this creature.

[ Gentle music plays ] The Creature: See what a wretched outcast I am?

I am similar to them.

Mary Shelley: But also strangely unlike them.

Crowe: Mary Shelley is the key anchor for this entire story.

So the framing device for this piece is how Mary Shelley planted the seeds for what would become Frankenstein.

Mariani: Her mother passed away when she was 11 days old, so she never knew her.

She had a few babies who passed away.

Friendly: And it's very intentionally set up to kind of weave in between the two.

Like what maybe was she working through with this story?

In the novel, isolation is the overwhelming theme, the isolation of the creator and the isolation of the creation.

The Creature: I will make you so wretched that the light of day shall be hateful to you.

Friendly: Nobody has really tried to explore that in a big way.

Crowe: I've been looking for a Frankenstein script for about 20 years, but none of them really kind of sparked my interest the way this one has.

Spark, I say.

[ Laughs ] Narrator: By returning to Mary Shelley's classic story with its fleshed out, intelligent creation, what is old becomes new again, and there's nothing more Frankensteinian than that.

Mary Shelley: The human heart can endure suffering -- for a while at least.

Singh: I think the sympathetic turn echoes a larger cultural change over the last 70 years, in particular.

A greater recognition of the humanity in the different or the other.

This is the same trend that is behind the rise of disability rights, behind the gay rights movement, second wave and third wave feminism, the civil rights movement.

All of these are about a reorientation in how we view the other and the marginalized.

We needed the monster that was created by human hubris and human weakness.

The sympathetic turn has re-shifted, relocated monstrosity from the monstrous to the people who deny humanity in the monstrous.

Salam: Questions about morality, a lack of humanity, of rejection.

If that's not the question of humankind, then what is?

And no story, in my opinion, deals with these questions like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

Crowe: The theater is a much more exciting place, I think, to see things than -- I mean, as much as I love film, there's something very different when you're in the room breathing the same air as the people who are telling the story.

Gartley: To sit here and have the monster look right at you and not just be scared, but see what that monster is thinking, hear what he is saying, and then feel what he is feeling.

You can't get that feeling anywhere else outside of the theater.

Wade: Mm.

Mm, mm, mm.

My favorite line of the show.

It's not one that's said by the creature but it's one of Mary Shelley's lines.

"The human heart is fragile.

It must be held with care with two gentle hands."

And that line gets me every single time.

It's one of my favorites.

[ Dramatic music plays ] Narrator: That's it for this episode of "State of the Arts."

Find more stories at StateoftheArtsNJ.com Thanks for watching.

[ Jazz music plays ] [ Jazz music continues ] [ Jazz music continues ] [ Jazz music continues ] [ Bright music plays ]

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S44 Ep3 | 8m 55s | The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey mounts a fresh take of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (8m 55s)

Food for the Soul: the Trenton Community A-Team

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S44 Ep3 | 6m 28s | The artists of the Trenton Community A-Team show how creativity can foster resilience. (6m 28s)

Oh God...Beautiful Machine: A work by Yusef Komunyakaa & Vince di Mura

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S44 Ep3 | 8m 27s | Oh God...Beautiful Machine: A work by Yusef Komunyakaa & Vince di Mura (8m 27s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by:

State of the Arts is a local public television program presented by NJ PBS