In Order to Be Free (May 1754 – May 1775)

Episode 1 | 1h 56m 9sVideo has Audio Description

Political protest escalates into violence. War gives thirteen colonies a common cause.

American colonists oppose efforts by the British Crown and Parliament to seize greater control in North America, escalating simmering tensions over land, taxes, and sovereignty into violent confrontation. After protestors dump tea in Boston Harbor, the British government enacts martial law in Massachusetts. Fighting at Lexington and Concord ignites a war that will last eight years.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Episodes presented in 4K UHD on supported devices. Corporate funding for THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by The Better Angels Society and...

In Order to Be Free (May 1754 – May 1775)

Episode 1 | 1h 56m 9sVideo has Audio Description

American colonists oppose efforts by the British Crown and Parliament to seize greater control in North America, escalating simmering tensions over land, taxes, and sovereignty into violent confrontation. After protestors dump tea in Boston Harbor, the British government enacts martial law in Massachusetts. Fighting at Lexington and Concord ignites a war that will last eight years.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The American Revolution

The American Revolution is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

MOMENTS: The Revolutionary War Card Game

Use your knowledge of Revolutionary-era moments to build a timeline of real historical events.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipAnnouncer: Major funding for "The American Revolution" was provided by The Better Angels Society and its members Jeannie and Jonathan Lavine with the Crimson Lion Foundation and the Blavatnik Family Foundation.

Major funding was also provided by David M. Rubenstein, the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Family Foundation, the Lilly Endowment, and by Better Angels Society members: Eric and Wendy Schmidt, Stephen A. Schwarzman, and Kenneth C. Griffin with Griffin Catalyst.

Additional support was provided by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Pew Charitable Trusts, Gilbert S. Omenn and Martha A. Darling, the Park Foundation, and by Better Angels Society members: Gilchrist and Amy Berg, Perry and Donna Golkin, The Michelson Foundation, Jacqueline B. Mars, the Kissick Family Foundation, Diane and Hal Brierley, John H.N.

Fisher and Jennifer Caldwell, John and Catherine Debs, The Fullerton Family Charitable Fund, and these additional members.

"The American Revolution" was made possible with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and Viewers Like You.

Thank You.

Announcer: The American Revolution caused an impact felt around the world.

The fight would take ingenuity, determination, and hope for a new tomorrow to turn the tide of history and set the American story in motion.

What would you like the power to do?

Bank of America.

♪ Voice: From a small spark, kindled in America, a flame has arisen not to be extinguished.

Without consuming, it winds its progress from nation to nation, and conquers by a silent operation.

Man finds himself changed and discovers that the strength and powers of despotism consist wholly in the fear of resisting it, and that, in order to be free, it is sufficient that he wills it.

Thomas Paine.

[Explosion] [Drum beating slow rhythm] Voice: We know our lands are now become more valuable.

The White people think we do not know their value, but we are sensible that the land is everlasting.

Canasatego, Spokesman for the Six Nations.

[Woman singing in Native American language] Narrator: Long before 13 British colonies made themselves into the United States, the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy-- Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Tuscarora, Oneida, and Mohawk-- had created a union of their own that they called the Haudenosaunee-- a democracy that had flourished for centuries.

Voice: We heartily recommend union.

We are a powerful confederacy.

And by your observing the same methods our wise forefathers have taken, you will acquire fresh strength and power.

Therefore, whatever befalls you, never fall out one with another.

[Canasatego] ♪ Narrator: In the spring of 1754, the celebrated scientist and writer Benjamin Franklin proposed that the British colonies form a similar union.

He printed a cartoon of a snake cut into pieces above the dire warning "Join, or Die."

A few weeks later at Albany, New York, Franklin and other delegates from 7 colonies agreed to his Plan of Union-- and then went home to try and sell it.

But when the plan was presented at the colonial capitals, each of the individual legislatures rejected it because they did not want to give up their autonomy.

[Cannonfire] The plan died, but the idea would survive.

20 years later, "Join, or Die" would be a rallying cry in the most consequential revolution in history.

♪ Voice: We are in the very midst of a revolution the most complete, unexpected, and remarkable of any in the history of nations.

Objects of the most stupendous magnitude, and measures in which the lives and liberties of millions yet unborn are intimately interested, are now before us.

John Adams.

[Explosion] Narrator: The American Revolution was not just a clash between Englishmen over Indian land, taxes, and representation, but a bloody struggle that would engage more than 2 dozen nations, European as well as Native American, that also somehow came to be about the noblest aspirations of humankind.

It was fought in hundreds of places, from the forests of Quebec to the backcountry of Georgia and the Carolinas; from the rough seas off England, France and in the Caribbean, to the towns and orchards of Indian Country.

[Gunshots] The fighting would take place on roads and in villages and cities; by woods and fields, and along waterways with old American names: the Susquehanna, the Tennessee, and the Ohio; the Oriskany, the Catawba, and the Chesapeake; and along waters with newer names: the Charles, the Hudson, and the Schuylkill; the Brandywine, the Cooper, and the Ashley; and finally the York.

The war grew out of a multitude of grievances lodged against the British Parliament by British subjects living an ocean away in 13 otherwise disunited colonies.

It was also a savage civil war that pitted brother against brother, neighbor against neighbor, American against American, killing tens of thousands of them.

[Gunfire] Voice: However great the blessings to be derived from a revolution in government, the scenes of anarchy, cruelty, and blood, which usually precede it, and the difficulty of uniting a majority in favor of any system, are sufficient to make every person who has been an eyewitness recoil at the prospect of overturning empires.

Abigail Adams.

Narrator: The American Revolution was the first war ever fought proclaiming the unalienable rights of all people.

It would change the course of human events.

♪ Man: It's our creation myth, our creation story.

It tells us who we are, where we came from, uh, what our forebears believed, and, and, and what they were willing to die for.

That's the most profound question any people can ask themselves.

Woman: What the American Revolution gave the United States was an actual idea of a moment of origin, which many other countries in the world don't have.

And it has invested these particular years of these particular people with a set of stakes that are so far beyond what any set of events and any set of people can plausibly carry that it has made the way that Americans think about this period very unreal and detached.

Man: One of the most remarkable aspects of the Revolutionary War is that you had such different places come together as one nation.

I'm not sure there is a state, anywhere in the world, in the late 18th century, that has as wide variety of people who inhabit it, um, and so, it really is actually kind of remarkable, the way that that nation ends up cohering, not around culture, not around religion, not around ancient history.

It was coming together around a set of purposes and ideals for one common cause.

[Soldier shouting orders] Voice: Events like these have seldom, if ever before, taken place on the stage of human action.

For who has before seen a disciplined army formed from such raw materials?

Who that was not a witness could imagine that men who came from the different parts of the continent, strongly disposed to despise and quarrel with each other, would become but one patriotic band of brothers?

George Washington.

♪ [Gunfire] Voice: We have great reason to believe you intend to drive us away.

Why do you come to fight in the land that God has given us?

Why don't you fight in the old country and on the sea?

Why do you come to fight on our land?

Shingas, Lenape Nation.

♪ Narrator: For several generations, violent conquest and Old-World diseases had decimated Native populations between the Atlantic Ocean and the Appalachian Mountains, where, by the middle of the 18th century, 13 distinct British colonies were established south of French Canada and north of Spanish Florida.

Now, as land speculators and settlers eyed the Ohio River Valley beyond the Appalachians, the paramount question became who would control the North American interior.

Both Protestant Britain and Catholic France-- ancient enemies that had already fought 3 wars in North America-- claimed the region.

So did a host of Indian nations who had lived and farmed and hunted there for hundreds of generations.

In 1754, to solidify Britain's claim, the Royal Colony of Virginia dispatched militia to protect their interests in the Ohio Country.

The small force of militiamen and a handful of Native allies surrounded a group of unsuspecting French soldiers... Man: Fire!

[Gunfire] and fired into them.

Nearly half of the Frenchmen were killed or wounded.

The rest surrendered.

According to one of the Indians with the Virginians, the militia's 22-year-old commander had been the first to shoot into the enemy's encampment.

If so, George Washington fired the very first shot of a global conflict that would come to be called the Seven Years' War and set the stage for the American Revolution.

Soon after his surprise attack, a French and Indian force surrounded Washington and his men, forcing him, for the first and only time in his life, to surrender.

A less prominent young man's military career might have ended there, but Washington was given a second chance the following year as aide-de-camp to General Edward Braddock, the British commander sent to dislodge the French at Fort Duquesne.

Braddock was confident his red-coated British regulars could easily defeat anyone who stood between him and the fort.

[Gunfire] But on July 9, 1755, a much smaller French and Indian force overwhelmed them.

The British panicked.

Braddock was mortally wounded.

The Command fell to Washington.

Two horses were shot from under him.

Musket balls ripped through his hat and jacket.

He ordered a retreat and managed to get most of his men safely off the battlefield.

Washington learned two valuable lessons: British troops were not invincible, and there was no shame in retreating if you could live to fight another day.

He was hailed as a hero and given overall command of Virginia's militia.

But after his appeal for a Royal commission in the British Army was rejected, he retired from military service in 1758 and returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon, filled with resentment at how the British had treated him.

Man: And he comes to view the people in London as people who have a condescending view of Americans.

They think of him as inferior.

They didn't give him a commission.

I mean, when Washington is told that he didn't get a commission, he doesn't think that means he's inferior.

He thinks that means the British are really stupid.

Voice: There can be no sufficient reason given why we, who spend our blood and treasure in defense of the King's Dominions, are not entitled to equal preferment.

We can't conceive that being Americans should deprive us of the benefits of British subjects.

[Washington] [Cannonfire] Man: The Seven Years' War, against Britain's imperial rivals, France and Spain, is fought not only in North America.

It's fought in the Caribbean, it's fought in Africa, it's fought in India, it's fought in the Philippines.

So, even though it starts in the Ohio backcountry, with a dispute between colonists and the French and their Indian allies, it mushrooms into a global campaign that touches Europe and all parts of the world.

The American colonies are just one piece on a broad, global Imperial chessboard as far as British policymakers are concerned.

Narrator: Remembered in North America as the French and Indian War, the fighting went on for years until a series of British victories, won by regulars and colonial troops, ended the French Empire's presence on the continent, gave Britain Spanish Florida, and more than tripled the lands claimed by England's King.

Man: France transfers to Britain all of its territory in North America.

But it's a little bit like the Greek myths, you know, never wish for something too much 'cause you might get what you wished for.

The British, in North America, have been hoping and praying for the defeat of the French for 80 years.

And now they're victorious.

Church bells are ringing.

This is the moment we've all hoped for.

And then it all begins to go to hell in a hand basket.

♪ Woman: Britishness in America is just everywhere.

In Boston, the Town House sits at the center of Queen and King Streets.

The London Bookshop was around the corner.

The Crown Coffee House.

The sort of ideal of, uh, fashion, of political currency, of the basis of one's rights and that sense of home.

They talk about Britain even when they have never been there as home.

Narrator: On Saturday, December 27, 1760, a British frigate anchored in Boston harbor.

It brought with it big news.

King George II had died in October.

His 22-year-old grandson now reigned as George III.

Crowds cheered.

Bostonians were proud to be part of what had become the most far-flung empire on Earth.

Man: In the 18th century, the belief was, who in the world has got it right?

Only one people on Earth-- the British.

They have a mixed constitution, constitutional monarch, House of Lords, an elected House of Commons.

You got an element of democracy, element of aristocracy, element of monarchy.

The 3 of them will check and balance each other and produce the perfect combination.

Vincent Brown: We tend to think of the British Empire in America as the 13 North American colonies that became the United States.

But Great Britain actually had 26 colonies in America.

And, by far, the most important of those, the most profitable, the most militarily significant, and the best politically connected of those colonies were those colonies in the Caribbean.

The territories that tended to have the most slaves, and exploit enslaved labor most intensively, tended to be the most profitable colonies.

So, if you look at North America, for example, Massachusetts is the least profitable colony in North America and it's got the smallest percentage of slaves in its territory.

The most profitable colony in North America is South Carolina.

Then, when you get to a place like Jamaica or Barbados, where 90% of the population is enslaved, then you're really talking.

That's where the money is being made and that's also why that's where the Royal Navy warships are concentrated.

Narrator: But the 13 contiguous colonies that clung to the Atlantic seaboard were the most populous.

The colonists' numbers had doubled every 25 years.

By 1763, the population-- Black and White-- had reached almost 2 million.

Christopher Brown: And those settlers produce for the Empire, but they also consume.

They provide markets.

They purchase goods that are manufactured in Britain.

It's the fastest-growing part of the British economy, is the trades with North America.

Man: The British Empire expanded enormously as a result of the Seven Years' War.

There's real anxiety that unless this empire is tied together more tightly, by central control and direction, it will start to fragment, in much the same way as the Roman Empire was assumed to have collapsed.

Narrator: For more than 150 years, London had treated its North American colonies with what one British politician would call "salutary neglect."

Each colony was part of the King's dominions, but in most of them, legislatures, elected by propertied White men, made laws, levied taxes, and decided how they'd be spent.

Slavery was legal everywhere, from New Hampshire to Georgia.

Many of the Black people living in the colonies had been born there or in the Caribbean.

But tens of thousands were from West Africa-- captured from what is now Senegal, Gambia, and Gabon; Angola, Congo, and the Ivory Coast; Nigeria, Cameroon, and Ghana.

Christopher Brown: I think it's easy to underestimate the sheer diversity and variety, um, in the colonies.

Close to the majority of the population in the southern colonies are African.

There are French Huguenots; there are Germans.

There's Scots.

There's Scots-Irish.

There are Native people, not just on the frontiers, but actually living in the heart of the 13 colonies.

Man: Most of the population of North America is Indigenous.

70%, 80% of the continent is still controlled by Indigenous people, politically, economically, and militarily.

It's not a separate place, it's not this timeless space where Native people are sort of existing in harmony with nature and that they have no interest in the outside world.

Native people want the good stuff that Europeans are bringing.

Europeans want the wealth that they can get from Native people.

Native powers are as important to the global market economy as a place like Virginia or a place like New York.

Voice: If there is a country in the world where concord, according to common calculation, would be least expected, it is America.

Made up as it is of people from different nations, speaking different languages, and more different in their modes of worship, it would appear that the union of such a people was impracticable.

Thomas Paine.

Narrator: In Britain, 2% of the population-- lords and lesser gentry-- owned 2/3 of all the land, and most people had for centuries lived "dependent" lives, either as tenant farmers, working land belonging to aristocrats, or as landless laborers working for an employer.

For most free White men in the colonies, North America was a land of opportunity.

Taylor: The people who are coming from Northern Britain, as well as a lot of Scots-Irish, often are bringing the resentments that they'd been pushed off their lands by landlords.

And so, there's a great sensitivity about any kind of financial exaction that could be a slippery slope leading to the kinds of dependence that they had escaped from.

Narrator: The colonies were overwhelmingly agricultural.

Just 3 seaport towns-- Philadelphia, Boston, and New York-- were home to more than 10,000 people.

And 2 out of 3 farmers were independent, proud owners of their land.

Others were indentured servants, hoping that once they fulfilled their contract, that they, too, could prosper on their own.

Woman: For Americans, land and liberty are completely intertwined.

White Americans see their liberty as being founded on not being a peasant on somebody's else's land.

Preserving, promoting that liberty for White Americans, to them, means taking Native land.

There is no other answer.

Calloway: American colonists had been looking forward to the glorious day when the French and their Indian allies would be defeated, and British subjects would sweep over the Appalachian Mountains, looking for land.

Woman: Maps at the time show the colonies extending well into the interior.

We often see maps as benign, as descriptive, as without argument.

But they're aspirational, in many ways.

They're an argument rather than a conclusion.

DuVal: Hundreds of Native nations still are completely intact, completely independent.

In the north, is the powerful Haudenosaunee League, the Six Nations, including the Mohawks and the Senecas.

To their south are the Shawnees, who have retaken the Ohio Valley in recent years and formed a huge confederacy that stretches from the Delawares, or the Lenapes, in the east to the powerful nations, including the Anishinaabe of the Great Lakes.

South of there are the Chickasaws, the Cherokees, the Choctaws, the Creek Confederacy, or the Muscogees, and hundreds of other smaller nations.

These are nations that fight against each other, but also that increasingly, by the late 18th century, are making some larger confederacies, in part to try to fight against settlers who have been moving onto their land in recent years.

[Thunder] Narrator: Beginning in the spring of 1763, in what was called Pontiac's War, warriors from at least a dozen Native nations overran many of the British forts along the Great Lakes and in the Ohio Valley and raided settlements, killing or capturing 2,000 colonists and driving out some 4,000 more.

Many colonists responded by killing any Indian they encountered.

Calloway: The Brits look at this situation and say, "OK, we've just inherited all of this empire.

"How on earth are we gonna stop this kind of thing happening again and again, and again?"

Narrator: The British concluded that Native Americans and colonists needed to be separated, at least for a time, and so, in 1763, a Royal Proclamation declared all the territory beyond the Appalachians off-limits to settlement or speculation.

Man: That prohibits White settlers from moving into these interior worlds, the same interior worlds that many colonists felt like they had just fought for.

And many settlers become outraged that, uh, the British Crown has any form of imperial, um, recognition of these Indigenous populations.

A kind of racial animus has formed in the aftermath of the Seven Years' War, in which many British settlers come to resent all Indians.

Christopher Brown: It's not because the British Government is especially concerned about Native Americans.

It's because they don't want Americans spreading out, where they'll be even more difficult to control.

Part of British policy is British settlers will stay near the coast.

And part of the colonists' answer is, "No.

Sorry, we're not doing that."

Narrator: London hoped the Proclamation would pacify the frontier.

Instead, it infuriated those would-be settlers poised to move west and frustrated land speculators who saw fortunes to be made there.

Calloway: And that is a huge slap in the face and a blow to those elite colonial Americans who've been indulging in this investment.

Who are these people?

Household names: Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, George Washington.

Narrator: After abandoning his dream of serving as an officer in the British Army, George Washington had married an enormously wealthy widow, Martha Dandridge Custis, and had made himself still wealthier speculating in western lands.

He saw no reason to stop.

The law was only a temporary measure to "quiet the minds of the Indians," he said, and he directed his land agent to defy the Proclamation and "secure [for him] some of the most valuable Lands" beyond the Appalachians.

Man: I think the American Revolution was all about land.

It's easy to make the political kinds of arguments, but I think underpinning all of that was the possibility of expansion, um, was the conflict with Indian people.

Narrator: Now to enforce the hated law and to police the frontier, the British government resolved to station an army of 10,000 men in North America.

The cost would be enormous-- some 360,000 British pounds a year.

London did not have the money.

Years of war on 4 continents had doubled the national debt.

Britain was in the midst of a postwar depression, and British consumers were already burdened with higher taxes than were the subjects of any other European monarch.

The average British subject paid 26 shillings a year in taxes; the average New Englander paid just one.

So, some bright spark has the idea, "Well, let's tax the American colonists."

Right?

They should pay their share because, after all, we fought the war for them, and this is to defend them.

Narrator: In 1764, the Prime Minister, George Grenville, proposed a series of 3 parliamentary statutes, all meant to make the colonies help pay for their own defense.

The Currency Act, which forbade the colonists from issuing their own money, angered the tobacco-growing gentry of Virginia, who were especially hard-hit.

The Sugar Act imposed taxes on imports from the Caribbean, and to enforce it, the British Navy dispatched 44 ships to stop smuggling, enraging New Englanders, whose economy had long profited from it.

The rest of the colonies were largely unaffected.

London assumed Americans were too disunited, too divided by self-interest, to ever be able to present a united front.

But now, Grenville introduced a third tax-- the Stamp Act.

It would affect nearly every colonist in every colony.

No one would be able to obtain a license or a loan, transfer land or draft a will, earn a diploma, purchase a newspaper, or even buy a deck of cards unless it was printed or written on English-made paper that bore a stamp embossed by the Royal Treasury, for which they would have to pay.

For the very first time, Parliament planned to tax the 13 colonies directly.

The Stamp Act was scheduled to go into effect on November 1, 1765.

Taylor: Colonists said, "No taxation without representation."

What they meant was, no taxation except by our elected Legislature, here in our particular colony.

These taxes were very small, but the fear was, "If we give into this precedent, "if we pay the small Stamp Tax now, what will they do in the future?"

[Gavel banging] Narrator: In the Virginia House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry introduced a series of resolutions asserting that only the General Assembly of that colony had the "right and power to lay taxes" on its people.

Henry went on to declare that just as Julius Caesar had his assassin Brutus, George III should understand that some American resister was sure "to stand up in favor of his country."

When some delegates shouted "Treason!"

others who were present remembered he responded, "If this be treason, make the most of it!"

[Gavel banging rapidly] In Boston, 42-year-old Samuel Adams helped rally the opposition against implementation of the Stamp Act.

A failure as a brewer and as a collector of local taxes, Adams was a master of propaganda.

His mission, he once explained, was to "keep the attention of [my] fellow-citizens awake to their grievances."

Voice: If our trade may be taxed, why not our lands?

Why not the produce of our lands and everything we possess or make use of?

If taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal representation where they are paid, are we not reduced from the character of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves?

[Samuel Adams] Woman: In terms of masters of communication, Samuel Adams was really up there.

He has an amazing ability to translate a concept into easily digested words.

And, therefore, to make, um, what seem--what could seem like fairly abstract ideas very vital and very urgent, and he's tireless.

So, he's able to produce page after page after page, new offenses, new crimes, new injustices.

Narrator: Pamphleteers took up the cause, declaring the Stamp Act illegitimate.

Most of the colonies' 24 weekly newspapers-- the businesses that would be hit hardest--followed suit.

Those that didn't faced being shut down by their journeymen and apprentices.

Taylor: Newspapers are very important.

The colonial public is more literate than any other people in the world outside of Scandinavia.

There's also word of mouth, conversation, absolutely essential.

Man: It became very common to discuss how you govern people and how people are free.

These ideas had filtered into the general population.

Narrator: Those ideas now led to protests in the streets.

In Boston, in August of 1765, a crowd formed-- made up of men and a handful of women, free Blacks and runaway slaves, poorly paid or unemployed workers who resented the rich, and apprentices in their off-hours, just looking for trouble.

They hanged in effigy the local man designated to become distributor of stamps and went on to invade the home of the lieutenant governor, destroying everything in sight and carrying off all of his furniture and 900 British pounds in cash.

In Newport, Rhode Island, another mob surrounded the stamp distributor, forced him to resign, and to lead them in chants of "Property and Liberty."

In Charleston, South Carolina, White anti-Stamp Act protestors marched through the streets chanting, "Liberty!"

But when enslaved South Carolinians echoed their cries, frightened enslavers called out the militia to patrol the street.

The Maryland appointee was driven from Annapolis with only the clothes on his back.

By the time the Stamp Act was supposed to go into effect, none of the 13 colonies had an official in place willing to enforce it.

Schiff: Part of our Revolution I think we have largely sanitized.

I think we've forgotten much of the street warfare, of the anarchy, of the provocations that took place.

Voice: A black cloud seems to hang over us.

It appears to me that there will be an end to all government here, for the people are all running mad.

James Parker.

Narrator: When a crowd surrounded the British Army headquarters in New York City, General Thomas Gage made sure his men held their fire, for fear, he said, that 50,000 angry colonists would swarm into the city and start a civil war.

General Gage was in charge of all British soldiers in North America.

He had been sent to maintain peace on the frontier.

Instead, he had found himself at loggerheads with colonists convinced they were being denied their rights as Englishmen.

Gage understood what was happening.

Voice: The spirit of democracy is strong amongst them.

The question is not of the inexpediency of the Stamp Act or the inability of the colonies to pay the tax, but that it is contrary to their rights and not subject to the legislative power of Great Britain.

[Gage] Conway: Thomas Gage was married to an American.

He owned land in the colonies.

He was, in many ways, embedded within colonial society.

So, he was particularly reluctant, I think, to engage in conflict.

Taylor: In the colonial world and the European world, democracy had a bad name.

It was a synonym for "anarchy."

It had a reputation as being turbulent, as a system exploited by ruthless politicians called "demagogues"-- people who pandered to the passions of common people in order to whip them up and get them to do passionate things, and to get government to serve them and to prey upon the property of more wealthy people.

So, democracy is not the aspiration that creates the Revolution.

The Revolution creates the conditions for people to aspire to have a democracy.

Narrator: Meanwhile, hundreds of merchants in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia pledged to boycott British goods until the Stamp Act was repealed.

To keep up the opposition, some lawyers, merchants, and skilled craftsmen established an association, the Sons of Liberty, and soon had chapters from Portsmouth, New Hampshire to Charleston, South Carolina working together.

Voice: The colonies until now were ever at variance and foolishly jealous of each other; they are now united for their common defense against what they believe to be oppression; nor will they soon forget the weight which this close union gives them.

Dr.

Joseph Warren.

Narrator: The colonies now accounted for 1/3 of Britain's trade.

With the boycott, some manufacturers were forced to close their doors.

Thousands of workers lost their jobs.

The town councils of 27 English trading and manufacturing towns pleaded for repeal.

By mid-February 1766, the British cabinet was looking for a way out of the impasse.

It asked Benjamin Franklin, then living in London as a lobbyist for Pennsylvania, to appear before the House of Commons, hoping that hearing from the best-known American on Earth would help.

Franklin patiently answered 174 questions.

What had been the colonists' attitude toward Great Britain before the Stamp Act was enacted?

Voice: The best in the world.

They had not only a respect but an affection for Great Britain; for its laws, its customs, its manners, and even a fondness for its fashions, which greatly increased the commerce.

[Franklin] Narrator: "Would the colonies now accept a compromise?"

he was asked.

"No," he answered.

"It was a matter of principle."

"Might a military force compel the colonists to pay the tax?"

"No," Franklin said.

Voice: Suppose a military force is sent into America.

They will find nobody in arms.

What are they then to do?

They cannot force a man to take stamps who chooses to do without them.

They will not find a rebellion.

They may indeed make one.

[Franklin] ["Rule Britannia" playing] Narrator: 8 days after Franklin's testimony, the House of Commons voted to repeal the Stamp Act.

British workers would return to their factories.

Merchant vessels set sail again for the colonies.

When the news reached America in April, the Sons of Liberty disbanded; their rights as Englishmen seemed to have been restored.

New York commissioned a statue of King George, wearing a Roman toga, to be placed on the Bowling Green at the tip of Manhattan.

But beginning in the summer of 1767, the British government, still struggling with war debt, would win passage of 5 new laws--the Townshend Acts.

One of them especially angered colonists.

It imposed new taxes on 4 items manufactured in England-- glass, lead, paper, and painter's colors-- and on a fifth item, tea, grown in China but re-exported from Britain and loved by the colonists, rich and poor alike.

Newspaper editors and pamphleteers denounced the new taxes.

A revived and more militant Sons of Liberty called for a new boycott of British goods.

Women, who normally played a subordinate role in public life and had almost no legal rights, joined the resistance by the thousands as "Daughters of Liberty."

Woman: Crisis changes people.

And it gave women different ideas about what they should be doing.

DuVal: Women were the main consumers in colonial society and they were the ones who made sure the boycotts worked.

Women stopped drinking tea.

Women started making their own fabric.

Women started making toys for their children.

And they didn't just stop buying British things and start making their own things; they publicized it.

Taylor: One of the key forms of political theater during the Resistance Movement would be for a local minister to invite the women of the community to come down to the church and to spend the day spinning and weaving cloth.

And it would be a competition to see which community could produce the most homespun.

It would be published in the newspaper.

And these women would be praised as great American Patriots for having produced so much homespun cloth.

DuVal: And reporters would report, "The ladies of Boston, "The ladies of New York "are the most patriotic.

They are at the forefront of this protest movement."

If women hadn't done that, the protest movement and eventually the Revolution would have gone nowhere.

Voice: Let the Daughters of Liberty nobly arise, And though we've no voice but a negative here, Stand firmly resolved and bid them to see, That rather than freedom, we'll part with our tea.

Hannah Griffitts.

Voice: I wish to see America boast of Empire-- of Empire not established in the thralldom of nations but on a more equitable base.

Though such a happy state, such an equal government, may be considered by some as a Utopian dream; yet, you and I can easily conceive of nations and states under more liberal plans.

Mercy Otis Warren.

Narrator: The political philosopher and historian Mercy Otis Warren would publish plays and poems that satirized Royal officials with names like Judge Meagre and Sir Spendall.

No woman played a more important role in promoting resistance.

Tensions with England continued to grow.

In Boston, in June of 1768, a ship called the "Liberty" was seized by the Royal Navy.

Its owner, John Hancock, was the richest merchant in the city, a prominent member of the Sons of Liberty-- and a practiced smuggler.

A big, angry crowd formed at the wharf.

Voice: The mobs here are very different from those in Old England.

These Sons of Violence are attacking houses, breaking windows, beating, stoning, and bruising several gentlemen belonging to the Customs.

Ann Hulton.

Voice: The town has been under a kind of democratical despotism for a considerable time.

And it has not been safe for people to act or speak contrary to the sentiments of the ruling demagogues.

Thomas Gage.

Narrator: On orders from London, General Gage sent two regiments of regulars from Nova Scotia, not to defend Boston, but to police it.

Most Bostonians were appalled.

Woman: An army during wartime makes sense.

Of course, you need that.

But an army during peacetime is a standing army.

And if you have an army during peacetime, the thinking is that its only use is to turn on poor, innocent subjects.

Voice: To have a standing army!

Good God!

What can be worse to a people who have tasted the sweets of liberty?

Things are come to an unhappy crisis.

All confidence is at an end.

And the moment there is any bloodshed, all affection will cease.

Reverend Andrew Eliot.

Voice: The spirit of emigration to America, which seems to be epidemic through Great Britain, is likely to depopulate the Mother Country, and leave our ancient kingdom the resort of owls and dragons, and other solitary animals, who shun the light, and seem displeased at the human race.

"The Edinburgh Amusement."

[Bell tolling] Narrator: The steadily rising tensions between England and its North American colonies did not slow the steady stream of English, Scots-Irish, German, and a small number of Jewish immigrants eager to carve out new lives within the North American interior.

Christopher Brown: Part of what really sets the North American experience apart is just how many European settlers are coming to North America.

[Horse nickers] And they keep coming.

15,000 a year.

A kind of empire was already in view.

Narrator: Thousands of new arrivals and American-born colonists poured down the Great Wagon Road that ran all the way from Philadelphia to the Carolinas.

The backcountry there was already the home of Native peoples, including the Catawbas and Cherokees.

Voice: Upon the whole, it is the best country in the world for a poor man to go to and do well.

And the farther they go back in the country, the land turns richer and better.

Here, a man of small substance, if upon a precarious footing at home, can, at once, secure to himself a handsome, independent living, and do well for himself and posterity.

All modes of Christian worship are here tolerated.

"Scotus Americanus."

Taylor: Colonial America is a very Protestant place.

And it's founded when the norm in Europe was that whoever your sovereign was got to set what the religion should be.

Narrator: Congregationalism was the established church in nearly all New England colonies.

The official religion in much of the South was the Church of England.

But those who belonged to other faiths resented being forced by colonial legislatures to pay the salaries of clergymen who did not minister to them.

None were more resentful than the backcountry settlers in the Carolinas-- Baptists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Methodists.

Taylor: And what they hear from their ministers about whether resisting their sovereign or supporting their sovereign is the right thing to do as a Christian duty, that will matter a lot.

[Drum beating rhythmically] Voice: I was born in Boston in America in the year 1760.

In the time I was at school, the troubles began to come on.

And I was told the day of judgment was near at hand, and the moon would turn into blood, and the world would be set on fire.

John Greenwood.

Narrator: Shortly before noon on Saturday, October 1, 1768, 8-year-old John Greenwood left his home in Boston's North End and hurried toward the waterfront.

There, riding at anchor in a great arc, he saw 14 British warships, their cannon trained upon the city.

Boats swarmed between the ships and the end of Long Wharf, ferrying hundreds of British red-coated regulars.

General Gage's occupying army had arrived.

The crowds that lined the street were for the most part silent and sullen.

But it was not the history being made that impressed young John Greenwood that day.

It was the irresistible music played by Afro-Caribbean men and boys in colorful uniforms.

Voice: I was so fond of hearing the fife and drum played by the British that somehow or another, I got an old split fife, and fixed it by puttying up the crack to make it sound, and then learned to play several tunes.

I believe it was the sole cause of all my travails and disasters.

[Greenwood] [Fife playing upbeat tune] Narrator: Before long, the boy was playing well enough to become a fifer for a local militia.

"The flag of our company," he remembered, "was an English flag."

They would not be English forever.

Half the newly arrived troops were housed in barracks on Castle Island, but orders from London had been clear.

It was "His Majesty's pleasure," they said, that the rest of the troops "be quartered in that town."

[Man shouting orders] For 17 months, Boston was an occupied city.

The rattle of drums awakened residents every morning.

Passersby were routinely stopped and searched.

Many soldiers had brought their wives and children; others courted Boston girls, or were pursued by them.

40 troops were married during the occupation, and more than 100 of their offspring were baptized.

But some soldiers got drunk, robbed people, insulted women, profaned the Sabbath.

There were brawls, stabbings, suits and countersuits.

From London, Benjamin Franklin was concerned.

Voice: Some indiscretion on the part of Boston's warmer people, or of the soldiery, may occasion a tumult.

And if blood is once drawn, there is no foreseeing how far the mischief may spread.

[Franklin] Narrator: On the evening of March 5, 1770, there were tussles between Bostonians and British soldiers all across the city.

At the Royal Customs House, a crowd of young men surrounded a lone sentry and pelted him with snowballs and chunks of ice.

Convinced a city-wide uprising was underway, Captain Thomas Preston raced several armed grenadiers to the scene.

More snowballs and rocks and oyster shells greeted them.

They fixed bayonets.

[Bells tolling] Zabin: Somebody starts ringing the church bells, which in Boston is a sign for fire.

Some people are bringing buckets to be part of a bucket brigade.

Some people are drawn by the noise.

It's very hard, in fact impossible, to know what happened, which is that somebody yells, "Fire."

[Gunfire] All we know really is that when the smoke cleared, there are 5 people dead or dying.

Narrator: The first was a tall dock-worker-- part Native-American, part African-American-- named Crispus Attucks.

The second was a ropemaker named Samuel Gray, who was standing next to Attucks.

The third was James Caldwell, a sailor who was in town, it was said, to call upon the girl he hoped to marry.

The terrified crowd began to scatter.

John Greenwood's older brother Isaac was there, too, and escaped unharmed, but a ricocheting ball hit their friend Samuel Maverick in the back.

He died in agony the following morning.

Maverick, an apprentice, had shared a bed in the Greenwood home with the now 9-year-old John, who recalled that after his friend's death, he deliberately slept in pitch-black darkness, hoping "to see his spirit."

Zabin: People start arguing, already, even before they go to bed, about what happened.

Paul Revere creates probably the most famous engraving of the 18th century, which he titles the "Bloody Massacre."

The British Army is very anxious to try to spin this as a story of self-defense... but the language of massacre is the one that holds.

Narrator: A fifth man, a leathermaker named Patrick Carr, would die several days later.

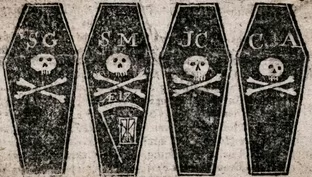

10,000 mourners accompanied the coffins of the dead to the Old Granary Cemetery.

Voice: The Fatal Fifth of March can never be forgotten.

The horrors of that dreadful night are but too deeply impressed on our hearts-- when our streets were stained with the blood of our brethren; and our eyes were tormented with the sight of the mangled bodies of the dead.

Joseph Warren.

Narrator: Not everyone was grieving.

An Anglican clergyman, Mather Byles, asked a fellow cleric, "Which is better, "to be ruled by one tyrant 3,000 miles away or by 3,000 tyrants not a mile away."

[Gavel banging rapidly] Captain Preston was found not guilty of ordering his men to fire.

The other 8 soldiers were put on trial separately.

Samuel Adams' younger cousin, John Adams, risking his reputation, served as the soldiers' attorney.

Most of his clients were acquitted as well.

Two were found guilty of manslaughter.

They were branded on their right thumbs so that if they were ever charged with another crime, they could not make a claim of innocence again.

The British government was relieved by the outcome of the trials.

Most of the regulars were withdrawn to Castle William-- their harbor fortress.

Once again, American colonists had forced the British to back down and Parliament had already repealed all but one of the Townshend Acts.

Only the duty on tea remained.

♪ Voice: Yorktown stood unrivaled in Virginia; its commanding view, its vast expanse of water, its excellent harbor.

It was the seat of wealth and elegance, one of the most delightful situations in America, at least, my infantine imagination painted it so.

Betsy Ambler.

Narrator: Betsy Ambler was 6 years old in 1771-- the oldest child in a prominent Yorktown, Virginia family.

A young Thomas Jefferson had once hoped to marry her mother, Rebecca, but she had married Jacquelin Ambler instead.

He insisted that all his daughters get a proper education.

He was a planter and merchant in Yorktown, the bustling deepwater port near Virginia's colonial capital at Williamsburg.

On Yorktown docks, enslaved Africans entered America, and the tobacco they harvested went out to the world.

Though Betsy's father was the Royal Collector of Customs, he and his family had grown more and more sympathetic to their neighbors' calls for liberty.

Voice: Young as I was, the word "liberty" so constantly sounding in my ears seemed to convey an idea of everything that was desirable on Earth.

True, that in attaining it, I was to see every comfort abandoned.

[Ambler] Voice: Thomas Hutchinson, Governor of Massachusetts: There is now a disposition in all the colonies to let the controversy with the kingdom subside.

Hancock and most of the party are quiet and all of them abate of their virulence, except Samuel Adams.

[Hutchinson] Narrator: For 2 years, Samuel Adams kept up a steady stream of essays, in which he warned again and again that the lull was only temporary, that Parliament remained bent on imposing tyranny.

♪ Kamensky: Those who have interests in keeping the political story alive and growing, have to really work to keep it front and center, to define the problem as something present in the minds of ordinary people.

Why would I care about this as a--as a woman?

Why would I care about this as a small farmer?

[Sawing] Narrator: In 1772, events beyond Boston gave Adams the ammunition he needed to spread his radical message throughout the colonies.

In April, when a sawmill owner in New Hampshire was charged with commandeering pine trees earmarked for the masts of royal warships, a mob drove the British officials who came to arrest him out of town.

[Fireball] In June, when the "Gaspée," a British customs schooner, ran aground while chasing smugglers, angry Rhode Islanders set it afire.

And that fall, Adams learned that beginning the following year, the British Treasury would use the revenue from tea to pay the salaries of the most important Massachusetts officials, including all the colony's judges.

The judges' first loyalty would now be to the Crown, not the colonists.

There would be no way to ensure impartial justice.

Adams drafted a fiery response.

Voice: Among the natural rights of the colonists are these: First, a right to life; secondly, to liberty; thirdly to property; together with the right to support and defend them in the best manner they can.

[Samuel Adams] ♪ Narrator: Printed copies of his writings were sent to town meetings throughout the colony.

So-called Committees of Correspondence soon linked advocates of resistance in more than 100 Massachusetts towns and districts.

Eventually, their network would spread into other colonies.

Schiff: "Committees of Correspondence" is an effort to try to bring all of the colonies onto the same page, to make them feel as if they have a common cause, words which had really not been used before.

And it's through those committees that, essentially, the Revolutionary spirit diffuses itself throughout the colonies.

Voice: Let not the iron hand of tyranny ravish our laws and seize the badge of freedom.

Is it not high time for the people of this country explicitly to declare whether they will be freemen or slaves?

Samuel Adams.

Voice: I need not point out the absurdity of your exertions for liberty, while you have slaves in your houses.

If you are sensible that slavery is, in itself, and in its consequences, a great evil, why will you not pity and relieve the poor, distressed, enslaved Africans?

Caesar Sarter.

Kamensky: Slavery as a metaphor is in the conversation from the beginning.

Everywhere there's slavery, there are people thinking about freedom.

Nothing shows the desire for freedom like the struggles of subject peoples.

Voice: I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate Was snatch'd from Afric's fancy'd happy seat: What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent's breast?

Steel'd was that soul and by no misery mov'd That from a father seiz'd his babe belov'd: Such, such my case.

And can I then but pray Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

Phillis Wheatley.

Narrator: Phillis Wheatley, who was stolen from Senegambia in West Africa and taken to Massachusetts as a young girl, was renamed for the slave ship the "Phillis" that brought her and the Wheatley family that bought her.

In Boston, the Wheatleys saw to her education, and as a teenager, still enslaved, her "Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral" won favor on both sides of the Atlantic.

It was the first published book by an African-American writer.

Voice: How well the cry for liberty, and the reverse disposition for the exercise of oppressive power over others agree, I humbly think it does not require the penetration of a philosopher to determine.

[Wheatley] Voice: I wish most sincerely there was not a slave in the province.

It always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me-- fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.

You know my mind upon this subject.

Abigail Adams.

Voice: Ye men of sense and virtue-- Ye advocates for American liberty-- Bear a testimony against a vice which degrades human nature and dissolves that universal tie of benevolence which should connect all the children of men together in one great family.

The plant of liberty is of so tender a nature that it cannot thrive long in the neighborhood of slavery.

Benjamin Rush.

Christopher Brown: Part of what happens in the years before the American War is that liberties are kind of broken out of a national context.

These are not English liberties.

These are transcendent liberties.

These are liberties that all individuals have by the nature of being human.

[Waves crashing] Man: Heave away!

Voice: The Americans have made a discovery, or think they have made one, that we mean to oppress them.

We have made a discovery, or think we have made one, that they intend to rise in rebellion.

Our severity has increased their ill behavior.

We know not how to advance.

They know not how to retreat.

Some party must give way.

Edmund Burke.

Narrator: In October of 1773, 7 ships set out from Plymouth, England for North American ports.

The cargo hold of each was filled with crates of tea.

It all belonged to the Crown- chartered East India Company, which was on the brink of bankruptcy.

To save the company, Lord North, the Prime Minister, had won passage of a new Tea Act, designed to undercut smuggling and reduce the cost of tea.

Kamensky: It seemed to Parliament like a "Win-Win-Win."

Shore up the East India Company, take it more in-house as a governmental organization, and give Americans cheaper, non-smuggled tea at the same time.

Narrator: But colonial merchants who had profited handsomely from smuggling portrayed the new law as yet another assault on American rights.

John Adams wrote that immediate resistance was necessary because of its "attack upon a fundamental principle of the [British] constitution."

No American had consented to the tea tax; therefore, no American need pay it.

Government-appointed tea agents were to be persuaded-- or coerced--into refusing to receive any tea.

In Charleston, South Carolina, the Sons of Liberty "convinced" an agent not to accept the shipment meant for him.

In Philadelphia, the Governor of Pennsylvania talked a ship's captain into sailing back to Britain.

In Boston, when 3 of the ships loaded with tea arrived, thousands of Bostonians and supporters from outlying towns gathered at the Old South Meeting House and declared that the tea should remain on board and be sent back to Britain.

On December 16, 1773, hundreds looked on from shore as between 50 and 60 men-- rich as well as poor-- all crudely disguised as Native Americans, climbed into boats and headed for the ships.

Deloria: They dress like Indians, kinda.

It's an expression of what it is to be American.

When you claim to be Indian, you're claiming to be here, aboriginal, part of this continent.

And you're drawing a really bright line between yourself and the Mother Country.

[Crates smashing; people shouting] Narrator: The men banged open 342 crates and poured more than 46 tons of tea into the harbor.

[Splashing] No other property was disturbed.

And when one of the boarders was seen filling his coat pockets with fistfuls of tea, he received a "severe bruising."

Taylor: This is an assault on the property of the East India Company, and it's an assault upon the pride and the power of Parliament.

So, it's a very big deal.

Protesting taxes is one thing.

Destroying private property worth thousands of pounds sterling, that's something else.

Narrator: In Manhattan, the King had grown so unpopular in some quarters that royal officials thought it prudent to surround his statue with an iron fence.

A law warning of the dire consequences for anyone who dared deface the statue... [Gunshot] did not prevent one New Yorker from firing a musket ball through its cheek... [Gunshot] and another one through its neck.

♪ Voice: The study of the human character opens at once a beautiful and a deformed picture of the soul.

We there find a noble principle implanted in the nature of man.

But when the checks of conscience are thrown aside, or the moral sense weakened, humanity is obscured.

Mercy Otis Warren.

Voice: The most shocking cruelty was exercised a few nights ago upon a poor old man named Malcolm.

There's no law that knows a punishment for the greatest crimes beyond what this is, of cruel torture.

Ann Hulton.

Narrator: In Boston, in January of 1774, a small boy on a sled accidentally ran into a minor customs official named John Malcolm, who cursed and threatened to beat him.

When George Hewes, who had helped dump the tea into Boston harbor, tried to intervene, Malcolm knocked him unconscious with his cane.

[People shouting] Malcolm was hauled from his house.

He was stripped nearly naked, hot tar was poured over him, scalding his flesh, and then he was covered with feathers.

♪ Jasanoff: Tarring and feathering is something that has come down to us as an almost kind of comical thing because you see these people with chicken feathers on them, but this is hideous stuff.

Boiling pitch is poured onto somebody's skin.

The burns are unbelievable.

And it's all part, also, of a kind of spectacle of violence that is a really important part of this.

And this is why the feathers are put on, in part.

It's that you are trying to humiliate and shame the victim.

[Shouting continues] Narrator: Hundreds jeered as Malcolm was pulled through the freezing streets for 5 hours.

His assailants stopped here and there to whip him.

It would be 8 weeks before he was able to leave his bed.

♪ Voice: Boston has been the ringleader of all violence and opposition to the execution of the laws of this country.

Boston has not only therefore to answer for its own violence but for having incited other places to tumults.

Lord North, Prime Minister.

Narrator: Lord North hoped, he said, to make America lie "prostrate at his feet."

They "must fear you," he added, "before they will love you."

Now that they had destroyed Crown property, it was clear that much of America was not afraid.

North would do his best to change that.

In the process, he would try to end every vestige of self-rule prized by the people of Massachusetts.

First, the Prime Minister convinced the Parliament to repeal that colony's long-standing charter, then dissolved the elected assembly again and limited each town and village to just one town meeting a year.

The port of Boston would be closed until all its residents had paid in full for the tea just 60 of them had destroyed.

That came to nearly 5 British pounds per taxpayer-- more than a craftsman made in a month.

It means no ships going in, no ships going out, no work for sailors, no work for merchants.

It means hunger in Boston.

Narrator: British officers were also now empowered to commandeer vacant homes and barns to quarter their troops.

Americans would denounce the new laws as the "Intolerable Acts."

♪ In England on leave, General Gage was summoned by George III.

He told the King what he wanted to hear.

The people of Massachusetts pretended to be "lyons," he said.

But if England sent in enough troops, they would undoubtedly "prove very meek."

General Gage was given a new title-- Governor of Massachusetts in addition to Commander-in-Chief-- and a new mission: to enforce the new Acts, end Boston's resistance, and demonstrate to all the colonies the folly of defying their King and Parliament.

Gage and 4 fresh regiments set sail for Boston in mid-April, 1774.

[Sheet flapping] Christopher Brown: The British Government sees this as a police action, that if they can punish Boston and shut down Massachusetts, contain the rebellion, that the other colonies would get the message and that order could be restored with some grumbling.

I think the British Government is genuinely surprised, um, to see the ways that the other 12 colonies rally to Massachusetts' cause.

Taylor: You are not gonna have an American Revolution unless you have Virginia onboard.

And the leaders of Massachusetts understood this.

It was not going to be easy.

There were deep prejudices between the two regions because of the differences in their ethnic mix and in the nature of their cultures.

And they hadn't previously had any kind of trust for one another.

Narrator: But in Virginia, the House of Burgesses declared a day of "fasting, humiliation and prayer" in solidarity with the people of Massachusetts.

And when the royal governor Lord Dunmore declared the very idea an insult to the King and dissolved the assembly, its members reconvened in Williamsburg's Raleigh Tavern.

The Virginians warned that "an attack made "on one of our sister colonies is an attack made on all British America" and called for a "Continental Congress" to meet in Philadelphia in September to see how the colonies might resist together.

All the 13 colonies except Georgia-- where people were afraid to lose British protection in the event of an Indian war-- agreed to take part.

The Prime Minister's effort to intimidate the other colonies by punishing Massachusetts had instead begun to unite them.

[Bell tolling] Voice: Lebanon, Connecticut.

Yesterday, the bells of the town early began to toll a solemn peal, and continued the whole day.

The shops in town were all shut and silent.

Our brethren in Boston are suffering for their noble exertions in the cause of liberty-- the common cause of all America-- and we are heartily willing to unite our little powers for the just rights and privileges of our country.

[Lebanon Town Meeting] ♪ Narrator: Now news of a new offense by the King's ministers-- The Quebec Act-- would bind them still more tightly together.

Jasanoff: The British decide that it would make sense to grant a degree of civil liberties to those French-speaking Catholics in Quebec in order to integrate them into British governance and make sure that they have a population that can sort of live with British authority.

Narrator: Protestants, who equated the Papacy with despotism, were outraged.

The Act also extended Quebec's borders west and south, adding to the fury of land speculators and would-be settlers.

DuVal: To British colonists, the Quebec Act was another slap in the face.

The British Government is looking more and more, with each of these acts, like the problem, instead of the protector that it's supposed to be.

♪ Narrator: That summer, beginning in Western Massachusetts, in town after town, crowds of angry armed men forced the resignations of the councilors, judges, and magistrates appointed by General Gage.

Juries refused to serve.

Courts closed down.

When Gage learned that rebels in the towns surrounding Boston had quietly begun to remove some of the precious gunpowder every town was allotted for its defense, he sent 250 soldiers to the stone powder-house in Charles Town to confiscate it.

Angry colonists saw the raid as yet another provocation.

[Horse nickers] The Massachusetts Assembly defiantly reconstituted itself and soon set about creating a clandestine provincial fighting force, tens of thousands strong.

Man: March!

There had been organized town militias in New England since the earliest days in case of trouble with Indians.

Every man between the ages of 16 and 60 was expected to arm himself and take part.

[Horse nickers] It was also now suggested that each town assign a quarter of its militiamen to a special company, ready to act, they said, at "a minute's warning."

Neighboring colonies followed the Massachusetts example.

[Tapping] The Connecticut Assembly urged every town to double its supply of gunpowder, ball, and flints.

Rhode Island ordered all militia officers to make their men ready to "march to the assistance of any Sister Colony" whenever they were needed.

Voice: The line of conduct seems now chalked out.

The New England governments are in a state of rebellion.

Blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent.

King George III.

♪ Voice: Philadelphia-- The regularity and elegance of this city are very striking.

It is situated upon a neck of land about 2 miles wide between the River Delaware and the River Schuylkill.

And the uniformity of this city is disagreeable to some.

I like it.

Front Street is near the river, then 2nd Street, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th.

The cross streets are named for forest and fruit trees-- Pear Street, Apple Street, Walnut Street, Chestnut Street, et cetera.

John Adams.

[Bell tolling] Narrator: In the autumn of 1774, when 12 colonies sent delegates to the Continental Congress, Philadelphia was the logical place to assemble.

It was home to some 40,000 people and was the most populous city in British America-- larger than New York, more than twice the size of Boston.

The delegates met in the newly constructed Carpenters' Hall, hoping to develop a common means of resistance while still somehow remaining within the Empire.

It would not be easy.

Adjacent colonies quarreled over borders.

Small ones feared domination by large ones.

And half the delegates were lawyers, fond of arguing.

Voice: This assembly is like no other that ever existed.

Every man in it is a "great man"-- an orator, a critic, a statesman--and therefore every man upon every question must show his oratory, his criticism, and his political abilities.

[John Adams] [Men arguing] Schiff: You have a group of men who have hailed from essentially different countries, who observe different religions, who conform to different habits, who are really meeting each other for the first time.

No one is really sure what to do, at first.

Is this meant to be a negotiation?

Is this meant to be another boycott effort?

Is this meant to be some kind of serious rupture with the Mother Country?

Voice: Their plan is to frighten and intimidate.

But supposing the worst, you have nothing to fear from anyone but the New England provinces.

As for the Southern people, they talk very high, but it's nothing more than words.

Their numerous slaves in the bowels of their country and the Indians at their backs will always keep them quiet.

Thomas Gage.

Narrator: General Gage assured London the Congress was a "motley crew," unlikely to achieve anything.

The "motley crew" included some of the colonies' leading political figures-- Samuel and John Adams from Massachusetts; John Jay, a young attorney from New York, convinced some solution short of war with the Mother Country must still be found; and Patrick Henry, who argued that ties with Britain had already been severed.

"The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers and New Englanders, are no more," Henry said.

"I am not a Virginian, but an American."

But a fellow delegate from Virginia spoke for many.

"Independency" was not the wish of any "thinking man in all North America."

Voice: I shall not undertake to say where the line between Great Britain and the colonies should be drawn, but I am clearly of opinion that one ought to be drawn.

The crisis is arrived when we must assert our rights or submit to every imposition that can be heaped upon us; till custom and use will make us as tame and abject slaves as the Blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.

George Washington.

Ellis: Most people in 1774 would say they're British.

They wouldn't say they're Americans.

The change happens in '75, '76, and the major source of it is a thing that's created called the "Continental Association."

The Association is an engine for creating revolution.

Narrator: The Continental Association was not a committee, but a phased program that forbade Americans from importing British goods as of December 1, 1774, from consuming British goods as of March 1, 1775, and barred them from exporting American goods to Britain beginning on September 10th-- if London still had not given in to their demands.

Among the so-called "British goods" the delegates intended to boycott were enslaved Africans-- whom they agreed not to import after December 1, 1775.

The delegates made plans to hold a second Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 6 months.

"We must change our Habits," John Adams wrote, "our Prejudices, our Palates, "our Taste in Dress, Furniture, Equipage, Architecture, et cetera."

To make sure Americans did so, every community was expected to establish its own Committee of Safety in order to "attentively observe the conduct of all persons."

By the spring of 1775, some 7,000 men had been elected to serve on such committees throughout the colonies, tasked with spying on their neighbors, opening their mail, poring over merchants' records in search of suspicious transactions.

Most of those suspected of failing to observe the boycott or who were overheard criticizing resistance were ostracized, their names and supposed crimes printed in the local newspaper, their neighbors forbidden even to speak with them.

[Men shouting] Ellis: Every town, every hamlet, every village has a Committee of Safety and Inspection.

And they go house to house.

You have to take a "Loyalty Oath."

There's millions of conversations.

And that's when the change happens.

Voice: If we must be enslaved, let it be by a King at least, not by a parcel of upstart, lawless committeemen.

If I must be devoured, let me be devoured by the jaws of a lion, and not gnawed to death by rats and vermin.

Reverend Samuel Seabury.

Narrator: Harassed, shamed, shunned, censored, sometimes attacked, opponents of resistance-- called "Loyalists"-- saw the Committees of Safety as more tyrannical than Parliament could ever be.

Nathaniel Philbrick: There was a sense of brutality that went with the Patriot cause that said, "No, you are wrong, and we are right."

To be a Loyalist didn't mean that you were evil.

It just meant that you felt a great sense of loyalty to the country that had made the prosperity that was the American colonies at this point possible.

Taylor: The Loyalists are essentially the conservatives.

They're the people who believe in law and order.

They don't like mobs.

They don't like committees telling them what to do.

[Thunder] They don't see King George III as a tyrant.

Voice: We are preparing for war.

To fight with whom?

Not with France and Spain, whom we have been used to think our natural enemies-- but with Great Britain, our parent country.

My heart recoils at the thought.

Andrew Eliot.

[Sea gulls crying] Voice: If a civil war commences between Great Britain and her colonies, either the Mother Country, by one great exertion, may ruin both herself and America, or the Americans, by a lingering contest, will gain an independency.

And in this case and whilst a new, a flourishing, and an extensive empire of freemen is established on the other side of the Atlantic, you will be left to the bare possession of your foggy islands.

Catharine Macaulay.

Narrator: General Gage now warned London: "The whole Continent has embraced the cause of the town of Boston."

Voice: If you think 10,000 men sufficient, send 20,000.

You will save both blood and treasure in the end.

A large force will terrify and engage many to join you.

A middling one will encourage resistance and gain no friends.

[Gage] Narrator: But General Gage was sent far fewer men than he'd hoped for.

And he was ordered to move decisively against the rebels and arrest their leaders.

Samuel Adams and John Hancock had fled Boston and found refuge with friends in Lexington, a small town-- just 750 people and 400 cows-- on the road to the larger town of Concord, some 18 miles northwest of Boston.

[Drums beating rhythmically] Gage planned to send troops through Lexington to Concord, where he had been told arms and provisions meant for a sizeable rebel army were hidden.

Success would depend on the strictest secrecy.

[Dog barking] Late on the evening of April 18, 1775, 700 British regulars were awakened, not told where they were going, and silently marched through the dark empty streets of Boston.

A fleet of boats was waiting to row them across the Charles River to the Cambridge marshes.

For all the care the British had taken to keep their plans secret, Dr.

Joseph Warren, one of Boston's leading rebels, got wind of it.

You don't move 1,000 men out of Boston in the middle of the night without arousing a response.

American rebel leaders send warning.

Two men, William Dawes and a silversmith named Paul Revere, are sent in different routes to alert Samuel Adams and others in Lexington that the British, in fact, are coming.

Narrator: Before the two men left, Revere saw to it that 2 lanterns appeared in the belfry of the Old North Church just long enough to alert sympathizers on the mainland that the regulars were crossing by water to Cambridge, not marching overland through Roxbury.

[Racing hoofbeats] Voice: Time will never erase the horrors of that midnight cry, when we were roused from the benign slumbers of the season with the dire alarm, that 1,000 of the troops of George III were gone forth to murder the peaceful inhabitants of the surrounding villages.

Hannah Winthrop.

♪ Narrator: Just after midnight on the morning of April 19, 1775, Revere reached Lexington and the house where Adams and Hancock were hiding.

"The Regulars are coming out!"

he shouted.

The two rebel leaders fled into the night.

[Bell tolling] Lexington's militiamen, summoned from their beds, dressed, gathered up whatever weapons they happened to own, and hurried to the town green.

Their commander was Captain John Parker, a farmer, who, like many of his 70 men, had fought alongside the British in the French and Indian War.

♪ Then, shortly before dawn, someone spotted 6 companies of redcoats-- about 250 men--approaching at a rapid clip.

On horseback in the lead was Major John Pitcairn, a Scottish veteran with nothing but scorn for colonists.

Captain Parker knew he could not stop the British, but he wanted to impress them with his men's resolve.

Parker told them not to fire first.

A British officer shouted, "Throw down your arms, ye villians, ye rebels, and disperse."

Atkinson: They begin to disperse.

Many of them turn their backs and start to walk away.

[Click, gunshot] A shot rings out.

No one knows where the shot came from.

Man: Fire!

[Gunshots] That leads to promiscuous shooting... mostly by the British.

[Heavy gunfire] It's not a battle.

It's not a skirmish.

It's a massacre.

Now blood has been shed.

Now the man on your left has been shot through the head.

Your neighbor on the right has been badly wounded.

You can't put that genie back in the bottle.

Narrator: 8 militiamen died on the Lexington Green.

9 more were wounded.

The rest fled.

Atkinson: The fact that the British have fired on their own people, which is how it's viewed by the Americans, causes an outrage that takes it to a new level in terms of resistance, a feeling that, um... "They're killing us, and the only thing "that we can do in response is to kill them as quickly as we can in numbers as profound as we can."

[Gunfire] Man: Charge!

Narrator: The British resumed their march toward Concord, now just 6 1/2 miles away.

[Bell tolling] Meanwhile, other riders fanned out across the countryside to spread word of what had happened.

Militiamen from nearby towns rushed toward Concord.

"It seemed as if men came down from the clouds," one man said.

It was not memories of the Stamp Act or the tax on tea that rallied them.

"We always had governed ourselves," one man remembered, "and we always meant to."

In Acton, 6 miles to the west of Concord, 40 Minutemen gathered at the home of their commander, Captain Isaac Davis, a 30-year-old gunsmith.

Voice: My husband said but little that morning.

He seemed serious and thoughtful.

As he led the company from the house, he turned himself round and seemed to have something to communicate.

He only said, "Take good care of the children," and was soon out of sight.

Hannah Davis.

[Gunfire] Narrator: The British seized 2 bridges spanning the Concord River and spread throughout the town.

[Glass breaks] They entered houses, broke into barns and outbuildings.