Chicago Stories

The Rise and Fall of the Mail Order Giants

11/10/2023 | 55m 41sVideo has Audio Description

Long before the age of online commerce, the mail order catalog was king.

In an age before online commerce and Amazon, the catalog was king – and two Chicago mail order giants were responsible for making goods and services accessible to the masses. Chicago Stories traces the histories of Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward and the rivalry between the two bold innovators who founded them and forever changed the way we shop. Audio-narrated descriptions are available.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Chicago Stories is a local public television program presented by WTTW

Lead support for CHICAGO STORIES is provided by The Negaunee Foundation. Major support is provided by the Abra Prentice Foundation, Inc. and the TAWANI Foundation.

Chicago Stories

The Rise and Fall of the Mail Order Giants

11/10/2023 | 55m 41sVideo has Audio Description

In an age before online commerce and Amazon, the catalog was king – and two Chicago mail order giants were responsible for making goods and services accessible to the masses. Chicago Stories traces the histories of Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward and the rivalry between the two bold innovators who founded them and forever changed the way we shop. Audio-narrated descriptions are available.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Chicago Stories

Chicago Stories is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Chicago Stories - New Season!

Blizzards that brought Chicago to a standstill. A shocking unsolved murder case. A governor's fall from power. Iconic local foods. And the magic of Marshall Field's legendary holiday windows.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Narrator] Coming up, millions of Americans shopped in their stores.

- Everything was just so up to date and so good.

You would wanna shop there yourself.

- [Narrator] And their catalogs inspired customers to dream big.

- The Sears and Wards catalogs, those were holy grail in my house.

- You knew this is the cornucopia of hope in the world.

Everything is in there.

- [Narrator] Mail order pioneers, Richard Sears and Montgomery Ward were polar opposites, one a brilliant businessman, the other a sensational salesman.

- [Ron] Sears himself was the mouth man.

He could sell.

- This guy Ward, he's for real and he's capable of delivery on his promises.

- [Narrator] They built retail empires and changed what Americans bought and how they bought.

- You would have a couple rail cars show up with every item needed to build a house.

- [Narrator] And their innovations would set the stage for today's retail giants.

- [Ron] What they're doing now, Sears and Wards both did a century and a half ago.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] The Rise and Fall of the Mail Order Giants... next on "Chicago Stories."

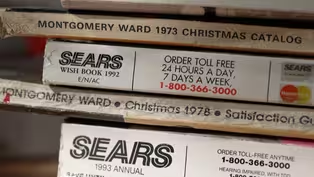

(gentle music) (train rumbling) Long before everything in the world was available with the click of a mouse or swipe of an app, eager children all over America watched and waited for the mailman, in anticipation of the herald of the holidays: the Sears and Montgomery Ward holiday catalogs.

- I think immediately of the wish book for Christmas and just how thick it was.

- I absolutely remember looking at the catalog as a kid and like other children, took a pen, circled things that I wanted.

Obviously the wish book was every kid's fantasy.

- The toys that we weren't able to get, those were the ones that you pretended you had looking in the catalogs.

- That was like a Christmas present on its own.

It was such a delight to go through that catalog.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Today, in the era of Amazon, it's hard to imagine a time before direct order and delivery.

But without one man, none of it may have ever happened.

Mail Order Magnate, Aaron Montgomery Ward.

He didn't invent buying by mail, but he recognized its potential.

- He refined it or even, you could argue, perfected it.

And the way that he was able to do that is by drawing on his own firsthand experiences.

- [Narrator] Ward was born in New Jersey in 1844, the son of a farmer.

- He came from an old distinguished east coast family, but it was a large family without a lot of money.

- [Narrator] At the age of 14, young Monty Ward left school to earn his keep working a string of odd jobs at a barrel maker and a brickyard.

But manual labor didn't suit him.

When he was offered a job as a store clerk, he jumped at the chance.

The young man had a knack for understanding customer needs.

And before long, he was appointed store manager.

Ward yearned for bigger stakes, so the 22-year-old set off for Chicago, where he took a job as a traveling salesman with the forerunner of Marshall Field's.

On the road, Ward sold to country stores.

He noted that these shops weren't big enough to carry much variety, and there was little competition in the small towns to keep prices down.

- Ward saw people in rural areas were, in his opinion, being taken advantage of.

And he thought he could offer them better price, better deal, easier way to get an item by starting a mail order business.

- [Narrator] Ward imagined a new type of catalog business, a fully-stocked department store by mail, delivering a wide range of products at lower prices.

In the late 1800s, there was no better place than Chicago to launch his plans.

- It was the place to be because no city in the history of the world had ever gotten so big, so fast.

It was also the heart of the nation's railroad network.

You have all these raw materials coming into the city and they're being made into all of these goods.

- [Narrator] Manufacturers needed to get those goods to farms springing up all over the Midwest, spurred on by the Homestead Act offering free land to anyone, citizen or immigrant.

Ward drained his savings account to fill a warehouse with all the goods he'd need to launch his revolutionary start-up.

Then, just weeks before the first catalog was set to go out, Ward's dreams went up in flames, literally.

(fire crackling) - The Great Chicago Fire, it pretty much wipes out the city's business district.

But is he in any way held back by that?

No, much like the city itself, he quickly rebuilds.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Ward was undeterred.

He worked for almost a year to earn the funds to replenish his inventory.

And he developed a marketing plan.

During his travels, he had met The Grangers, an advocacy group that represented farmers' interests.

Ward bet he could appeal to this price-conscious group.

And in August 1872, his first catalog went directly to 40 of its members.

The one-page price list contained 163 products, knives and forks, red flannel, blankets.

The price for 10 yards of poplin fabric $1.25, a gold necklace $1.50.

Orders trickled in, but before the company could gain much headway, disaster struck again, this time in the form of bad press.

- The Tribune was skeptical if Wards would be able to deliver on their promise.

And if you were the consumer, why would you wanna buy a good from a retailer where you couldn't even go into the physical store to check it out in person?

The whole concept sounded suspicious to the Tribune.

- [Narrator] The article played on a catalog's biggest vulnerability, people were not used to buying goods sight unseen.

But Ward had a solution.

He promised his buyers, "Satisfaction guaranteed or your money back."

- If you wanna build trust with your customer, you have to guarantee to them that they're gonna get what they ordered.

- (Ron) Farmers are very honest people.

It is a virtue to a fault with them.

If you said it's guaranteed, it had to be guaranteed.

If you did it that way, people would tell the story, then you got more customers.

- [Narrator] The Tribune soon came to the same conclusion.

- [Kori] The Tribune publishes a longer story saying, hey, we did an in-depth investigation and this guy Ward, he's for real and he's capable of delivering on his promises.

- [Narrator] With that retraction, heavy advertising, and customers' word-of-mouth, the company took off.

In just two years, the one-page price list blossomed into a small, but robust catalog, filled with more than a thousand items.

Ward was a master marketer, but he took a soft sell approach.

- [Paul] Because he has this experience, having done work with his hands, he can relate to farmers.

He's gonna kind of inform his friends of the best products.

- [Narrator] The catalog was a business, but Ward saw it as something bigger, an expression of American values.

- Ward wanted to embody through his catalog, that kind of American ideal that anybody can pick it up and then get what they needed.

As long as you had the financial means and a mailing address, you could place an order.

- [Narrator] A banner in the catalog read, "We sell our goods to any person whatever occupation, color, or race."

In the decades after the Civil War, this policy was life-changing for Black customers who were often discriminated against in local stores and could now shop anonymously.

- If you were allowed in, right, then you certainly would've been limited to what you could buy.

The better goods would've been saved for white customers unfortunately.

And the beauty of the catalog is that they didn't know what color you were so long as the cashier's check or money order or the cash was in there when they got your order.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] As a Black consumer base grew, catalog shopping had another advantage.

- [Dilla] Being able to secretly obtain things of value.

And a lot of times houses were targeted because white folks knew who had the nicer things.

There were people who were able to retain some of those nice things because others were not aware that they had 'em and that's because they ordered them through the catalog.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Ward ran advertisements inviting new customers to request a catalog.

He wanted anyone and everyone to order, even those who could barely read or write or were non-English speakers.

- It said on their order blanks early on, if you don't write the English language too well, don't worry about it.

We have trained linguists here.

They'll be able to figure out what you want.

(train chugging) (train bell clanging) - [Narrator] Packaged goods rolled out of Chicago and arrived at rail stations across the country.

The catalog had now become known as the "Wish Book."

And answer wishes, it did.

Opening up a world of possibilities to rural folk.

Sewing machines became the top seller, easing the burden of what was viewed as women's work.

Another popular item was the pocket watch.

In 1883, railway companies created railroad time, which we now call time zones, to standardize schedules.

That innovation made it both practical and fashionable to know the time.

(watch ticking) Ironically, watch sales would eventually create a headache for Ward, because a box of abandoned watches would ultimately launch his biggest competitor.

(dramatic music) Back when Montgomery Ward was first starting his business, an 11-year-old boy in Minnesota named Richard Warren Sears left childhood behind when his father, a blacksmith, went bankrupt.

- Richard Sears started his life off in poverty.

He was not somebody who came from money whatsoever.

So he began as scrappy beginnings and he had to work at a young age to put food on the table.

- [Narrator] Sears went to work as a day laborer on neighboring farms, but by night he taught himself Morse code.

At age 16, Sears was hired as a telegraph operator at a local train station.

Ambitious and driven, Sears was promoted to station agent.

But he was also an opportunist, always looking for ways to make an extra buck.

- Richard Sears had a side hustle.

He was doing lumber, coal, anything he could get his hands on to sell.

Then one day a box of watches appeared that was cash-on delivery for a jewelry store.

- [Narrator] The jewelry store hadn't ordered the watches.

As the station agent, it was Sears' job to deal with unwanted merchandise.

When he contacted the manufacturer, he was offered the lot at a steep discount.

- Richard Sears bought those watches.

He then sold those watches up and down the railway, and that gave him the sales bug that we see today.

- [Narrator] This stroke of serendipity launched his watch business and changed the course of his life.

Sears' first customers were other station agents.

Then he started advertising his watches in local papers.

He quickly learned that the more outrageous the ads, the greater the sales.

- He would sometimes describe an item, maybe a little bit more fancy than it was just to get somebody's attention, but he absolutely knew how to use the power of the word to sell.

- [Narrator] His headlines often touted a model's low price, but the finer print would push a fancier one's features, creating demand for more expensive watches.

In just six months, Sears pulled in more than $5000, nearly 10 times the average annual household income at the time.

But Minnesota was small-time for a man with big dreams.

And in 1887, Sears moved the growing R.W.

Sears Watch Company to a more promising location: Chicago.

- People knew that if they came to Chicago, there was enough room for them to just shoot right up to the top.

- [Narrator] Like Montgomery Ward, Sears recognized the value of a guarantee.

He promised buyers that his watches would last for six years.

- If it stopped working, he would replace it.

This quickly became very expensive.

So he needed to hire somebody who would repair watches.

- [Narrator] A quiet young man named Alvah Roebuck was the first person to apply for the job.

- [Rob] He actually created a watch and gave it to Sears as part of his interview process.

Sears' response was, I don't know a lot about watchmaking, but it must be good if you're giving me this as an example of your work.

- [Narrator] Roebuck was hired on the spot.

With Roebuck at his side, Sears would set off to become one of the greatest salesmen of all time.

And, in doing so, would set the stage for a decades-long mail order rivalry.

(gentle music) In the late 1800s, Chicago had become an industrial powerhouse and the hub of the Midwest.

- The whole system works by having a place where all the manufacturers could send the stuff to you and you could send it out.

If you think about it, every railroad in America centers on Chicago.

- [Narrator] Montgomery Ward was already taking advantage of this.

But despite being in the heart of a fast-growing city, Ward made it a point of pride that he did not sell to customers in Chicago or any urban area.

Instead, he continued to focus on his winning formula, the rural customer.

The company quadrupled in size through the 1880s with annual sales topping $2 million, more than 64 million by today's standards.

During that same time, 25-year-old Richard Sears was working 18-hour days.

His company, which now sold jewelry as well as watches was successful, but Sears had burned himself out.

When an offer to buy the company for $72,000, more than $2 million today, came his way, he took it and returned home to Minnesota, leaving Chicago and Alvah Roebuck behind.

(train rattling) Meanwhile, Montgomery Ward probably didn't even notice the goings on at such a small competitor.

After years of driving hard bargains with suppliers, the 42-year-old stepped back and enjoyed the benefits of success, even sitting for a marble sculpture with his wife, Elizabeth.

- He's an avid bicyclist.

He gets into riding and raising horses.

When automobiles come along, he's one of the first people to buy an automobile.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Ward wasn't the only one living a better life.

Americans, particularly rural Americans, were enjoying a rosier economic outlook as homesteaders moved from subsistence farming to turning a profit.

- Montgomery Ward wanted the best for his customers.

So as he observed that more broadly living conditions were improving in the United States and that the spending power of his base of customers increased and improved, he wanted to offer them better quality goods.

- [Narrator] As Ward's merchandise, which ranged from plows to violins became more high end, the lower end of the market was left behind.

Richard Sears, despite now living a quieter life as a real estate investor back in Minnesota, saw an opportunity he couldn't resist.

- He joined back up with Roebuck, who had started the Alvah Roebuck Company, and then they made it the Sears and Roebuck Company.

- [Narrator] Sears' new strategy was to go head-to-head with Montgomery Ward in all categories by undercutting him on prices.

The first catalog in Sears' assault on Ward was launched in 1893.

- Many of the items sold through the catalog were what you'd call entry-level items or opening price point.

So because he was selling aspiration as well as cheap, some of these items really fit the bill of cheap.

- [Narrator] Features were stripped off to lower costs.

Materials downgraded.

Flamboyant copy pushed unbelievable bargains too tempting to resist.

Sears exploited the lower income customer who had no choice but to buy at the most affordable price.

- You end up buying that cheaper good, over and over.

And by the time you bought it three or four times, you could have bought that quality good but we refer to that as the poor tax.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Montgomery Ward had built his reputation over decades.

And now, Sears simply rode on his coattails, turning Ward's slogan "Cheapest Cash House in America," into his claim "Cheapest Supply House on Earth."

- That really gives you the sense of the differences between the two men.

I don't think Ward would ever make that claim probably because it couldn't be backed up by facts.

Sears isn't beholden to the same sort of level of rigor and he's gonna make the boldest claims that he can get away with.

- [Narrator] Sears' timing could not have been better.

An economic depression in the 1890s pushed many farm families back into poverty.

By aggressively targeting this segment of the market, Sears' new company made half a million dollars in sales in its first full year.

Montgomery Ward had little patience for Sears' copycat approach.

To draw a distinction between the two companies, he declared, "We sell everything except trash.

We do not wish to be classed with the numerous swindlers of our city."

It was true that, unbeknownst to customers, Sears sometimes sold distressed or discontinued merchandise, but it was his genius for marketing that lured customers in.

- [Rob] Richard Sears had a knack for hyping items up, selling things that people didn't know they wanted or needed until they saw it.

- [Narrator] It wasn't always the most honest.

If customers read the fine print, they would have known that a $1 sewing machine was really a needle and thread.

He also offered questionable cures for baldness, female trouble, and masculine trouble, for that matter.

To counteract any bad word-of-mouth, Sears touted customer service that went above and beyond.

- It was said that Sears was riding in a train one time.

And the conductor complained that his watch had fallen out of his pocket, crashed on the floor and was broke.

Sears got up, gave him his watch and said, Sears guarantees that a watch will not fall out of your pocket and be broken.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Marketing a guarantee like that wasn't the best long-term business practice, but Sears was impulsive and ran the business on instinct alone.

He didn't bother with the details, like financial reporting or inventory management.

Sears' reckless style unnerved his partner.

- Alvah Roebuck as a person was not a risk-taker.

He was not an entrepreneur like Sears.

Alvah Roebuck was a very simple person who wanted to give people value.

- [Narrator] Frequent cash flow problems gnawed at Roebuck, especially when it meant they couldn't buy inventory.

- There was a lot of chaos at the time.

Orders were coming in left and right.

And they were absolutely doing gangbuster sales.

However, sometimes the product that somebody ordered, they may not have had it on the shelf so they had to send a substitute.

- [Narrator] Out the door went a green suit when the request was for brown.

Sears gambled that if the price was low enough, most customers wouldn't bother to return it.

But enough of them did that the company was sliding towards financial disaster.

- [Rob] Alvah Roebuck became stressed out because the company was incurring debt.

He did not have faith in Richard Sears' financial abilities.

- [Narrator] Roebuck wanted out.

Three years after joining forces again, Sears bought his partner's shares for $25,000 and became the sole proprietor of a company teetering on the edge of a meltdown.

(gentle music) Yet Sears continued his fast and loose business practices.

He advertised a $10 men's suit, but he didn't actually have any in stock.

With orders piling up, Sears reached out to a supplier in New York.

- He said, "You gotta help me.

I need a thousand suits immediately."

And this man said, the person that you really need to contact is my partner in Chicago and his name is Julius Rosenwald.

- [Narrator] Rosenwald was already a Sears supplier.

In fact, the company owed him more than $30,000.

That past due bill opened up an opportunity far bigger than just supplying $10 suits.

Rosenwald could see the company had potential.

- [Peter] Rosenwald sat down to acquire half of Sears, Roebuck.

Most of the money was money that Sears owed anyway.

So Rosenwald had to put down relatively little cash.

- [Narrator] The company would keep its name since it was already established and because Rosenwald was worried that antisemitism would cause sales to drop, if customers knew one of the owners was Jewish.

It was 1895.

Sears and Rosenwald were both in their early 30s and willing to dream big, but their visions for the company were often at odds.

- Sears himself was the mouth man.

He could sell, right.

But he was not a detail guy.

- [Narrator] Rosenwald was.

He ushered in efficiency and good business practices, like paying bills on time, while Sears still concocted his wild marketing stunts.

- By this time, Sears was a much more established company.

Rosenwald believed that they didn't need the gimmicks.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] As Sears and Rosenwald jockeyed for control of the company, the US Postal Service began offering rural free delivery.

Catalogs and small packages could now be delivered directly to newly installed mailboxes, saving customers a trip to the post office.

Though other mail order companies were popping up, Ward and Sears were locked in competition to be the biggest and best, one-upping each other with increasingly colorful mega-catalogs.

- And then it just exploded from there.

I mean, when you read that catalog, you knew this is the cornucopia of hope in the world.

Everything is in there.

- Sears' book topped out at 770 pages with deals like, stoves for $19.76, shotguns priced at $2.98, and sewing machines as low as $5.95.

(gentle music) As the 20th century dawned, Sears surpassed Ward in sales for the first time.

Both companies had become pillars of the Chicago business landscape, each employing thousands of workers.

In this period of constant growth, Ward needed more space.

Next door to his Michigan Avenue warehouse, he constructed the tallest building in Chicago, a fitting headquarters for a giant.

Ward envisioned customers visiting the city and taking in the view from an open-air observatory at the top.

But there was a rub.

- [Ron] That beautiful lakefront at that point was just a mess.

'Cause after the Chicago Fire, they just dumped all the garbage in there.

- [Paul] And this upsets Ward quite a bit, because he feels the lakefront really is sort of the city's front yard.

- [Narrator] Ward took it upon himself to file lawsuits to force Chicago to clean the area up.

It took years, and several trips to court, but Ward's efforts ultimately created the 300-acre Grant Park in downtown Chicago.

Later, when the Field Museum proposed building a permanent home on park land, Montgomery Ward went back to court.

Referencing text on a historic map from 1836, Ward argued his case that the land could not be developed.

- "Forever open, forever free."

That's beautiful poetry, right?

Who knew that it was legally binding, but he insisted it was.

- His case was heard four times by the Illinois Supreme Court and dragged out for years.

- [Narrator] Ward's tenacity paid off, and eventually the Field Museum was forced to build south of the park, where it sits today.

In the only interview Ward ever gave, he tersely reflected on his victory.

"Had I known how long it would take me to preserve a park "for the people I doubt I would have undertaken it.

"I fought for the poor of Chicago not the millionaires."

While Ward engaged in civic battles, his company continued its explosive growth.

(gentle music) To meet customer demands, a massive fulfillment center was built at the edge of downtown.

Rail and telegraph lines entered the building.

The Post Office and all major shippers had offices on site.

The building was more than two city blocks long, and the thousands of employees found creative ways to get around.

- [Peter] At one point, there were boys on roller skates who went around, picking up items and putting them in a basket, which would then be sent up to be wrapped and shipped.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] By 1906, Sears had overtaken Wards in sales.

To service their customers, they also needed a bigger facility.

To finance construction Rosenwald sold stock in the company.

Once it went public, the owners became instant millionaires.

Richard Warren Sears was now worth $4.5 million, roughly $150 million by today's standards, a mere 20 years after starting his business with an abandoned box of watches.

Sears' new headquarters in Homan Square on Chicago's West Side spanned more than 40 acres.

It was a fitting landscape for the company, which by then had earned the title of the nation's largest general merchandiser.

The complex had all the same features as Ward's new warehouse, but it had also been ingeniously designed for maximum efficiency.

Nine decades before the advent of online retailers like Amazon and Zappos, Sears was perfecting speedy delivery.

All orders were shipped within two days.

The administrative building featured a brand-new invention, air conditioning.

And employees had access to all sorts of perks, including an on-site YMCA, athletic fields, a sunken garden, continuing education classes, and a medical clinic.

- Part of this was done because JR didn't believe in unions and believed that if employees were happy, they wouldn't want to strike and ask for additional amounts of money.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] Now that the company was on firm financial footing, Richard Sears often spent time away from the office at his country house or on vacation.

The trips provided a relief from his workaholic tendencies.

During Sears' absences, Rosenwald asserted his will.

He cut overhead, slashed advertising costs, and toned down some of Sears' more outlandish claims.

This new standard of restraint was profoundly irritating to Richard Sears.

- There was a certain amount of friction.

And finally, there were even some of Sears' close associates were beginning to side with Rosenwald.

- [Narrator] After returning from a trip in 1908, Sears announced that he was retiring.

At the age of 45, Sears walked away from the company he had founded.

His net worth was more than half a billion in today's dollars.

He told the press that he had quote, "earned for me something besides money, namely, a little relaxation and a little time for my family."

(gentle music) Now in complete control, Rosenwald overhauled the business.

Unlike Sears' view of their clientele as a market to be exploited, Rosenwald hewed closer to Montgomery Ward's view that customers should be protected.

He immediately stopped the sales of popular, yet dangerous, quack medicines that were often filled with addicting ingredients like heroin and cocaine.

- When he first took over as president and CEO, he put a premium on honesty.

- [Narrator] As unsafe or low-quality products exited the catalog, new and bigger ones appeared, Sears-brand cars for $395 and ready-to-build Sears homes.

- [Rob] You would have a couple rail cars show up with every item needed to build a house.

And those houses still stand today and have stood the test of time and quality.

- [Narrator] The company's stable growth and the riches that accompanied it afforded Julius Rosenwald the opportunity to foster another passion: philanthropy.

- There isn't any civic organization in Chicago, Black or Jewish that you don't find his name on the roll.

- [Narrator] Rosenwald's charity spread beyond Chicago when he partnered with Booker T. Washington to build more than 5,000 schoolhouses for Black children across 15 Southern states.

- This cool white guy from Chicago hanging out with this Black guy from the South.

That, to me, is what America could be if we tried hard enough.

- [Narrator] Rosenwald was generous with his employees as well.

- [Peter] Anybody who worked for Sears for a certain amount of time was given stock in the company.

People could work for years for Sears and become really quite wealthy.

- [Narrator] Even hourly workers could draw the equivalent of $300,000 today at the end of their careers.

The plan encouraged loyalty and longevity, but it also discouraged unionization since union workers might not get the same deal.

(gentle music) The growth of both Sears and Ward would be limited if not for the evolution of the United States Postal Service.

In 1913, it introduced "parcel post."

Packages up to 11 pounds could now be delivered right to the customer's doorstep.

It was the dawn of a new era for the mail order giants.

But another era was ending.

That year, Aaron Montgomery Ward died at the age of 69.

- Ward's death was front page news in the Chicago Tribune.

It included photos and spoke about how he not only created the successful mail order business, but he was a defender of the lakefront.

- [Narrator] Richard Sears didn't outlive Ward by long.

The following year he died of liver disease, at age 50.

(gentle music) As founders faded away, new leaders were lining up to take their places.

Among them, General Robert Wood, who had managed the supply chain for the Army's construction of the Panama Canal.

He was hired at Wards for his organizational prowess, but he also understood that one major innovation was changing how Americans shopped: the automobile.

- [Peter] A trip to town was no longer a big deal.

You didn't have to go in a horse and wagon or buggy.

You could just get in your Model T and take off for the nearest town.

- [Narrator] In addition to selling through catalogs, General Wood envisioned expanding to brick-and-mortar retail stores to service these newly mobile customers.

- He met with a lot of opposition to this idea.

Nobody at Wards really wanted to change.

Why would you change?

They had a model that was working really well.

- [Narrator] Discouraged, Wood was either fired or quit.

The historic record varies.

But a friend asked Wood if he wanted an introduction to the competition, Julius Rosenwald at Sears.

Rosenwald recognized Wood's genius.

And together the two men would transform the mail order giant into simply a giant.

(gentle music) Even as Sears and Wards expanded to brick-and-mortar stores, their hefty mail order catalogs continued to stuff America's mailboxes, and over the years became useful in ways beyond their primary purpose.

- They served as a way of sitting up taller at the kitchen table.

They were fodder for lighting fires.

- Out in the country, people would use it in lieu of toilet paper.

- My aunt would put her youngest boy in the playpen with the Sears catalog.

- My older brothers would open the Sears catalogs or the Wards catalogs up to the women's garments or undergarment section.

And then like, turn that page and leave it on your bed and then scream, "Mom!"

- I am sure that I am not alone in being a graduate of the bras and girdles, in stunning detail.

(bell clangs) - [Narrator] In the early 1920s, Americans were moving off the farm.

A majority of the population now lived in cities.

Along with that shift came regular paychecks and an appetite for new luxuries and conveniences.

It was the dawn of American consumerism.

Discount stores, such as Woolworths and S.S. Kresge, were attractive to customers who had previously ordered from catalogs.

- The reason why this five-and-dime approach was appealing to shoppers is because they could go touch and feel the items before having to pay for them.

- [Narrator] The mail order giants had different strategies for expanding into the retail game.

Montgomery Ward opened stores in small towns and in big city downtowns.

At Sears, General Robert Wood took a different tack.

He built stores where real estate was cheap, at the edge of cities, in what would grow to become the suburbs.

These locations had ample space for customers to park their cars.

- It allows Sears to gain an advantage over Ward.

There were already neck and neck in terms of the mail order business, but Sears gets out in front ahead in terms of the retail business.

- [Narrator] In the new stores, Sears showcased their house brands that became synonymous with quality.

Craftsman tools.

DieHard batteries.

Kenmore appliances.

And Allstate tires.

Wood and Rosenwald's gamble on retail proved to be a stroke of genius.

By 1925, annual sales climbed to $234 million, $60 million more than Wards earned.

(gentle music) Julius Rosenwald's extraordinary leadership had built Sears into one of the nation's most successful retailers.

After 30 years at the helm, he stepped down to concentrate on his greatest philanthropic gift, Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry.

- It was suggested that the museum be called the Rosenwald Industrial Museum.

He said, no, he really didn't think it was a good idea because it should be the people's museum.

- [Narrator] When asked to reflect on his success, Rosenwald maintained his signature humility.

- I always believed most large fortunes are made by men of mediocre ability who tumbled into a lucky opportunity and couldn't help but get rich.

Don't be fooled by believing because a man is rich that he is necessarily smart.

There is ample proof to the contrary.

- [Narrator] Rosenwald, who made the most out of his luck, died three years after this interview at the age of 69.

- At Sears, Roebuck and Company, General Robert Wood was at the helm, as the company faced one of its greatest battles.

(gentle music) - [Reporter] The stock market plummeted in October of 1929.

In one convulsive week, $30 billion in stock value vanished.

- [Narrator] The Great Depression crushed many retailers.

But Sears adapted.

Again recognizing that cars had become an important part of daily life, Sears created Allstate car insurance.

And the company's bet that parking lots would lure customers paid off big time.

By 1931, Sears earned more from its 370 stores than it did from catalog sales, allowing the company to maintain profitability in a down market.

Montgomery Ward was not so lucky.

It lost almost $9 million that year.

To stem the bleeding, Ward hired a new President, Sewell Avery.

He was not there to make friends.

- He was, to put matters bluntly, a fascist, a self-declared fascist.

He hated labor unions.

He thought that Roosevelt was the damnation of the country.

- [Narrator] Avery's nickname was Gloomy, due to his conservative approach.

He closed unprofitable stores, trimmed overhead, reduced product offerings and put the focus back on mail order.

- Avery tried to create a future for Montgomery Ward by looking at the company's past.

He didn't really want to expand in retail.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] But customers were flocking to retail stores.

Avery was eventually forced to follow Sears' lead, but increased real estate costs cut deeply into Wards profits.

To push Christmas toy sales in 1939, Ward offered a free book to children, one that would become synonymous with the holiday.

It was the creation of catalog copywriter Bob May.

- May used a combination of things to come up with a story: his own childhood holiday experiences, the story of The Ugly Duckling, and also he combined it with the story of St. Nicholas and the reindeer that already existed.

- [Narrator] Children loved the plucky young reindeer so much that Ward gave away more than 2 1/2 million copies.

When Rudolph's run at Montgomery Ward was over, creator Bob May asked for the copyright.

- [Kori] For Avery to give away this copyright just meant he didn't see a future for the Rudolph story.

- [Narrator] But one thing readers learned about Rudolph was not to count him out.

May wrote more stories, and his brother-in-law penned the famous song.

♪ Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer ♪ - That it.

♪ Had a very shiny nose ♪ - [Narrator] The song hit number one during Christmas 1949, and 15 years later, the animated TV special debuted.

- Won't you guide my slay tonight?

- It will be an honor, sir.

(all cheering) - [Narrator] And, as they say, this Chicagoan went down in history.

Since the beginning, both Sears and Ward had managed to avoid unionization.

Sears mostly used the carrot approach, keeping employees happy while Ward tended to use the stick.

Ward's employees had had enough.

In 1942, 7,000 workers voted to form a union.

When Sewell Avery refused to adhere to their terms, a strike was imminent.

But it was during World War II, and President Franklin Roosevelt demanded that all businesses avoid shutdowns that might cripple the war effort.

Still, Avery defied the President's direct order.

- Avery decides to take a kind of hard-line stance.

He's firm in his principles.

And one of his principles is he doesn't believe the government should have a role in these negotiations.

And so what happens is that the Roosevelt administration decides to come in and basically take control of Montgomery Ward.

And this happens in the most dramatic fashion possible.

- [Narrator] National Guard troops lifted Avery from his desk chair and marched him out of Ward's headquarters.

Avery eventually acquiesced to the government and his workers' wishes.

For the next decade, Ward stagnated under Sewell Avery's leadership, eventually giving up the number two spot to JC Penney.

No one came close to challenging Sears at number one.

The company was making more than $3 billion per year, cashing in on the post-war blossoming of American consumer culture.

The original low-price leader was no longer concentrating only on what customers needed.

It grew by catering to what middle-class buyers desired.

- Sears, Roebuck and Company's origins was price-conscious shoppers.

But through the years they'd moved up to a mid-tier retailer.

- [Narrator] As Sears turned its attention to customers with more money to spend, a new type of competitor sprung up.

In 1962, a new concept called Kmart was launched.

In Arkansas, Walmart opened its first store.

And in Minnesota an upscale discounter named Target debuted.

- Sears gave up market share to Walmart and Kmart who came in and scooped up all of those price-conscious shoppers.

- [Narrator] For now, Sears didn't feel a thing.

By 1963, it was riding high with the title of world's largest retailer.

More than half of American households had a Sears charge card.

And the company was diversified, with a growing amount of profits coming from the Allstate insurance division.

As CEOs came and went, the company kept up with the times.

Celebrity endorsements pushed a move into lifestyle brands.

Golf pro Arnold Palmer pitched clubs.

Mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary endorsed camping gear.

And actor Vincent Price hawked flooring.

- But now Sears Fiesta vinyl flooring is as colorful as Spain itself, and it never needs waxing.

- [Narrator] A job at Sears was a first paycheck for many.

- Working for Sears during my high school and college years was so much fun.

My best memories were selling the makeup, selling the wigs.

- [Announcer] It's really easy-care monofilic fibers.

You can pack or crush it.

Get caught in the rain with it, even shampoo it.

The curls just won't quit.

- Everything was just so up to date and so good.

You would want to shop there yourself.

- [Narrator] At Sears' old Homan Square complex, executives wanted new headquarters that befit their status.

- Sears, Roebuck and Company absolutely viewed itself as a premier retailer.

And as a premier retailer, they needed a premier headquarters, something iconic.

- [Narrator] Plans were drawn up for the Sears Tower.

And in 1974, the world's tallest building was completed.

110 stories represented the pinnacle of Sears' success.

But sometimes when you're sky high, there's no place to go but down.

From their lofty offices, leadership was out of step with cultural shifts.

The civil rights movement and women's liberation had reshaped expectations many workers had for advancement.

But it took the Federal government suing Sears before it significantly improved the percentage of Black, female, and Hispanic workers in management.

- I was promoted into being a catalog buyer.

I was not treated with the open arms by the men who worked there.

How could women possibly do their jobs?

It was not a welcoming atmosphere.

- [Narrator] It was a similar story at Montgomery Ward.

- I didn't see too many people that looked like me in the store.

So, I was one of the only Afro-American, as far as management in the store.

- [Narrator] One of Ward's bright spots was its Electric Avenue department, which sold stereos, appliances, and TVs.

Then, competition entered the market, the big box retailer.

- When the Best Buy moved down the street, and Circuit City down the street, and there's a Target coming.

Your job was to increase sales from one year to the next.

Your job was to increase the profit.

It got to be more difficult.

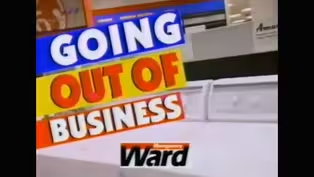

- [Narrator] Ward limped into the 1980s.

Its big book couldn't compete with the onslaught of specialty catalogs.

Mail order operations were shut down to focus on saving retail.

- So why shop anywhere else?

Electric Avenue at Montgomery Ward.

♪ Montgomery Ward, the brand name savings store ♪ - [Narrator] Sears was in danger too, but executives ignored alarm bells.

Retail sales were down, but revenue was up, thanks to profitable financial service offerings and the launch of the Discover credit card.

♪ The dawn of Discover ♪ - [Narrator] While executives focused elsewhere, Sears' retail dominance slipped away.

In 1990, Walmart overtook the sluggish giant as the country's largest retailer.

- One of the last heads of Sears said, "Sears is like a dinosaur.

"If you whack its tail with a baseball bat, "a decade later the impulse will get to the brain."

- When I worked at Sears, the younger guys that worked at the store, we always talked about how old the customers were.

It wasn't a place that my friends and I picked to shop.

- [Narrator] Not only were there new and more exciting places to shop, but by the mid 90's, there was an entirely new way to shop, the internet.

At first, the mail order giants tried to adapt.

- One of my last jobs was running their internet operation, as small as it was.

We got wards.com going.

We made some dollars with it, just very early stages of it.

- [Narrator] But the 125-year-old company couldn't hang on.

Montgomery Ward filed for bankruptcy in 1997 and closed all stores in 2001.

Sears was not much better off.

After discontinuing its once-famous catalog, rival Kmart corporation purchased Sears in 2005.

The combination of two struggling brands didn't revive either one.

Just as Amazon's Jeff Bezos was named the richest man in the world in 2018, Sears' parent company entered bankruptcy.

But Bezos' brainchild might not have ever been born if not for the mail order giants that came before him.

- Amazon has taken on the Sears of past to be the everything store to everyone.

- I just hope that Americans recognize that being able to go online and purchase things and not have to physically go anywhere, that concept comes from Montgomery Ward and Sears.

- [Narrator] At its height, one out of every 200 Americans worked for Sears.

Today, one in every 50 US workers is employed by Walmart or Amazon.

The downfall of Ward and Sears comes with a warning to those now at the top.

- There's always that danger, whenever a company becomes really successful.

Companies are always seeking ways to find new success and to increase profitability.

- There's perhaps a cautionary tale for retailers that wanna be everything to everybody.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] For more than 100 years, Sears and Roebuck and Montgomery Ward reigned supreme.

Competition to outdo each other inspired innovations, left an indelible mark on a city, and altered the very fabric of American life.

And though their names may have faded in this global, digital age, their impact is forever embedded in our country's commerce and consumer culture.

(gentle music)

The Early Business of Catalogs

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/10/2023 | 2m 56s | Aaron Montgomery Ward saw catalogs as an expression of American values. (2m 56s)

The Fall of the Mail Order Giants

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/10/2023 | 2m 25s | Once mail order and retail giants, Sears and Montgomery Ward struggled to adapt. (2m 25s)

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer Was Born in Chicago

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/10/2023 | 1m 37s | Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was born in Chicago thanks to a Montgomery Ward copywriter. (1m 37s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/10/2023 | 2m 22s | People found many uses for catalogs like the Sears Wish Book. (2m 22s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Chicago Stories is a local public television program presented by WTTW

Lead support for CHICAGO STORIES is provided by The Negaunee Foundation. Major support is provided by the Abra Prentice Foundation, Inc. and the TAWANI Foundation.