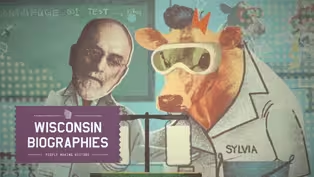

Wisconsin Biographies

Special | 26m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

Wisconsin Biographies tells the stories of notable Wisconsinites who have made history.

Wisconsin Biographies tells the stories of notable Wisconsinites who have made history. Featured in this compilation: Mohican teacher Electa Quinney, Chippewa activist Walter Bresette, electric guitar pioneer Les Paul, dairy scientist Stephen Babcock and recycling revolutionary Milly Zantow.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Wisconsin Biographies is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

Timothy William Trout Education Fund, a gift of Monroe and Sandra Trout.

Wisconsin Biographies

Special | 26m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

Wisconsin Biographies tells the stories of notable Wisconsinites who have made history. Featured in this compilation: Mohican teacher Electa Quinney, Chippewa activist Walter Bresette, electric guitar pioneer Les Paul, dairy scientist Stephen Babcock and recycling revolutionary Milly Zantow.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Wisconsin Biographies

Wisconsin Biographies is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Wisconsin Biographies tells the stories of notable Wisconsinites who have made history. Featured in this compilation: Mohican teacher Electa Quinney, Chippewa activist Walter Bresette, electric guitar pioneer Les Paul, dairy scientist Stephen Babcock and recycling revolutionary Milly Zantow.

Walter Bresette: Treaty Rights and Sovereignty

Video has Closed Captions

Bresette spoke on tribal sovereignty, American Indian treaty rights, and the environment. (4m 10s)

Stephen Babcock: Agriculture’s MVP

Video has Closed Captions

Stephen Babcock invented the Babcock Test at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. (5m 4s)

Milly Zantow: Recycling Revolutionary

Video has Closed Captions

Milly Zantow changed recycling in Wisconsin and the world. (5m 44s)

Les Paul: The Search for the New Sound

Video has Closed Captions

Les Paul’s groundbreaking music techniques are still used today in the music industry. (4m 40s)

Electa Quinney: Mohican Teacher and Mentor

Video has Closed Captions

Learn about the life of Electa Quinney, Wisconsin's first known public school teacher. (6m 42s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Announcer: PBS Wisconsin Education leverages the power of public media to spark curiosity and ignite learning in Pre-K settings through 12th grade.

Educational media can help build skills that students need to be successful.

PBS KIDS content and activities enhance school readiness and support children to reach their full potential in school and in life.

We also deliver award-winning educational media for elementary through high school classrooms.

Our media is aligned to state standards, and our locally-produced content is designed for and with Wisconsin educators.

We offer powerful and practical professional learning to support educators in activating all PBS resources, and we empower students to make their own media through our youth media initiative.

Be part of our service by sharing with an educator you know today!

Pbswisconsineducation.org.

[lively string and flute music] - Narrator: Electa Quinney was heartbroken to leave her home.

She was barely ten years old, and she and five other Mohican girls were going far away to school.

It would be a long time before they would see their families again.

But they knew that education was their best chance at surviving.

To understand why, we have to go back to the years before Electa was born.

[dramatic music] Electa and her family were Mohicans.

The Mohicans lived in a thriving community in the state now known as New York.

But by the 1700s, more and more European invaders were coming to America to seize land and resources.

Colonization, war, and European diseases decimated the Mohican populations and homelands.

In order to survive, the Mohicans were forced to move.

In the 1730s, they decided to live alongside some English colonists and form the town that became Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

There, the Stockbridge Mohicans raised families, farmed and hunted, and participated in town life.

When the Revolutionary War broke out, the Stockbridge Mohicans fought alongside the colonists against the British.

The American colonists promised to let them keep their lands in return for this service.

But after the war, they broke this promise and forced the Stockbridge Mohicans off their land and out of their homes.

Again.

Another tribe, the Oneida, offered the Stockbridge Mohicans a place to live in New York State.

So, they moved there and started rebuilding their community.

They called their new home New Stockbridge.

In 1797, several Stockbridge Mohican families sent their daughters to live and study with non-Native families.

Over several years, the girls learned reading, writing, and arithmetic, as well as crafts like knitting and how to make cheese and butter.

Their parents explained that a combination of Native teachings with a non-Native education would help the community understand and negotiate with American colonists.

Doing this would be key to their survival.

Back in New Stockbridge, the girls then shared what they'd learned.

One of them, Mary Peters Doxtator, opened a school for Stockbridge Mohican girls.

They produced cloth that they could sell.

The students would then share their profits to help care for the whole community, an important Mohican value.

Stockbridge Mohicans invested years building New Stockbridge.

Sending Electa and the other girls away to school was part of their work to keep this as their home.

But the New York state government and businesses were working hard to remove all Native people from the state.

Reluctantly, the Stockbridge Mohicans were forced to make their most devastating move yet-- into the unknown.

In the early 1820s, the Stockbridge Mohicans began their journey to the area that is now Wisconsin, where they signed a treaty with the Ho-Chunk and Menominee for some land.

They could only bring their most important possessions, and they had no way of knowing what life would be like so far from their homelands.

But the love of their people was so strong that they committed to doing what was necessary to ensure a better life for future generations of the Mohican Nation.

Electa Quinney was one of the people who helped carry Mohican traditions to Wisconsin from their homelands in the east.

When she arrived in Statesburg, now Kaukauna, in 1828, the Stockbridge Mohican community was busy rebuilding.

That summer, Electa started teaching in Statesburg.

That made her, a Native woman, the first known person to teach public school in the area that became Wisconsin.

Yes, the first!

She taught reading, spelling, math, and public speaking to Native and non-Native students alike.

Having a Native teacher at a school open to all students was an important sign of the Stockbridge Mohicans' generosity at work.

This was a big responsibility for Electa, but she came from a long line of tribal leaders, historians, diplomats, and educators.

Electa lived out her life as a cherished Mohican elder on a farm in the community.

When she died around 1885, she could rest knowing she had done her part to uplift her nation in the face of great obstacles.

Today, the Mohicans in Wisconsin call themselves the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans, and their reservation is in Shawano County.

They continue to be inspired by Electa Quinney.

Electa lifted up Native and non-Native people.

She taught not only school lessons, but demonstrated how to build a better society.

Her generosity is a defining Mohican value, one that the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans are still known for today.

- Bill Miller: ♪ She came here to teach us ♪ ♪ Her spirit still reaches ♪ ♪ Electa, you taught us so well ♪ ♪ Way ah ay ah way ah ay oh ♪ ♪ She came here to teach us ♪ ♪ Her spirit still reaches ♪ ♪ Electa, you taught us so well ♪ ♪ Way ah ay ah way ah ay oh ♪ [lively string music] [gentle acoustic guitar music] - Walter Bresette: I wanna begin at the beginning, and I always draw a map of Wisconsin, and I keep getting worse each time that I do draw it.

Here's Duluth, here's La Crosse.

I'm from this little community up here, which is the Red Cliff Reservation.

So I'm a Lake Superior Chippewa.

My village has a government-to-government relationship with the United States called sovereignty.

Laws, et cetera, need to take into account this concept of sovereignty.

And the treaties of 1837 and 1842 were basically deeds to real estate transactions.

You know, I'm sure there was something a little bit more than that going on.

We won't debate that here.

When that land was sold to the United States, there were easements on it.

The easement was that we would always have access to hunting, fishing, and gathering of the resources of this land.

So we sold the surface and the United States said, "Great."

Policies change, some years they like Indians, some years they ignore them, some years they try and get rid of 'em.

So back in 1974, here on the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation, there was a lake, but these young brothers said that perhaps that the state really never had authority to impose state game law against the Chippewa.

They would remember the old grandpa stories.

"Grandpa told me that his grandpa told him, "he was there when they signed those treaties.

And the treaties are our license."

So what they did was not unlike what Ghandi did, was not unlike what Rosa Parks did, was not unlike what anyone else did when they kind of knew in their heart that this law was not right.

They went across the imaginary line here and began spearfishing and, of course, they were arrested, cited for violating state game laws.

Well, to make that story shorter, in 1983, a three-judge panel in Chicago said Grandpa was right, that these young Tribble brothers had indeed stumbled onto lost rights.

They said, "We think that the state has been given "no constitutional authority for them to impose "against the Chippewa, who are the legal inheritors of these easements."

However, when the court ruled, they said, "You know, it's a long time since 1837 and 1842, "so what we want you people to do, to go argue the scope of these rights."

There is nothing in the treaties which say we must use the technology that existed when the treaties were signed.

So the Chippewa can do anything in terms of methods that are available that doesn't threaten the resource.

What was concluded was that wherever any of these resources are harvested by the general public, the Chippewa could harvest their portion of these resources.

Wherever anybody else can do it, we can do it.

And the tribal government understood for the first time that geez, this is a right.

Lost rights.

Rights that were never given up, were never sold, were never taken away, but were just usurped by might by the state of Wisconsin.

[gentle acoustic guitar music] [lively string music] [guitar strums] - Mike Bloomfield: This is a cherry Les Paul Sunburst guitar.

It's one of the greatest rock and roll guitars ever made.

- Rick Derringer: I just wonder if Les ever had any idea the kind of noise we'd all be makin' with these things.

His involvement in recording and in guitar recording, he's probably the number one man.

[slide guitar] - Les Paul: To begin at the beginning, I was born in Waukesha, Wisconsin.

And about the age of seven, something happened to me.

And I became interested in music and electronics.

I noticed this one fellow was winding this wire around this toilet roll, and I says, "Harry, what in the world are you doin'?"

He says, "I'm making a crystal set.

That's the newest thing, you know."

You can hear radio without no batteries, no nothing.

That led me into electronics very heavily.

So what I did is I stole my mother and father's radio, and I took 'em using this PA system.

To then, I jabbed the pickup needle into the top of the guitar and turned it on, started playin' a record and I played my guitar.

[electric guitar strum] I put that on a hollow-bodied guitar.

An unwanted condition developed.

So you've got a string doin' this and a pickup going up and down on the top of the guitar.

I'm saying, "Hey, only one thing should move, just the string."

No matter what I played from the early '30s on, I was totally convinced I had to pick something close to a solid-body instrument.

♪ Somewhere there's music ♪ ♪ How faint the tune ♪ ♪ Somewhere there's heaven ♪ ♪ How high the moon ♪ ♪ There is no moon above ♪ ♪ When love is far away too ♪ I went to the Gibson people and it took me about seven, eight years to finally convince 'em that this is the way to go.

And I said, "Okay," and we signed.

He says, "With one stipulation.

"We won't use the name Gibson.

What do you suggest?"

And I said, "Well, why don't you call it the Les Paul guitar?"

[electric guitar riffs] - Rick: Les Paul came into the picture.

Up until he really started experimenting with recording techniques, the only way you could record was with several mics, live, on two tracks of tape.

And the entire session had to be balanced accordingly.

If horns were used and they were louder than the bass player, well, that meant you put the horns farther away from the mic than the bass player.

And after the record was done, there was nothing to alter it.

[guitar strums] - Les: Bing Crosby asked me one day if I'd record a song with him.

Bing says, "Sounds fine to me."

And he says, "Les, what do you think?"

And I says, "I don't like it."

Bing says, "What's wrong with that record?"

And I says, "Aw, it's technical, Bing."

I says, "There's a lot of things that I desire that are not there."

[electric organ plays] Then the idea hit me, and I says, "I know where it's at.

"It's to stack up this machine with all eight tracks.

I can record each part individually."

Let's see, I've got my wife, Mary.

- Mary Ford: Hi, why don't you grab a guitar and show the people what you can do?

- Les: All right, I got a lot of ideas.

Here we go.

[guitar strums] Now, that's one guitar.

Now, if you want two, I just throw a switch.

[switch clicks] [guitar doubles] - Mary: How 'bout three?

- Les: Easy.

[switch clicks] [three guitar sounds play] Now, if you want four, switch.

[switch clicks] [guitars play] - Mary: How 'bout five?

- Les: It's a cinch.

[switch clicks] [guitars play] Now, if you want six, here's a half a dozen, an easy one.

[switch clicks] - Rick: He was really an innovator in modern recording techniques.

It's almost like he was the person who invented the sound of today's pop records.

- Mike: This is it, this is the sound.

[electric guitar plays] ♪ ♪ [lively string music] [musical fanfare] - Narrator: Welcome back to the 1890 Dairy Bowl, presented by the Wisconsin consumers.

We're here in beautiful Madison, Wisconsin.

The future of the world's dairy industry is on the line.

We're gearing up to watch the final minutes of this epic battle between the Wisconsin Honest Farmers and the Cheaters.

Let's take a moment to look at the action from the game so far.

In the first two quarters, Wisconsin Honest Dairy Farmers were controlling the field, but they've been losing ground ever since the game-changing play in the third quarter when they were stuffed at the production line.

That really changed this game's momentum.

The Cheaters had been watering down their milk and selling it like the real thing!

[crowd gasps] Real sneaky play.

The problem is the refs, or anyone for that matter, just can't see the foul.

Thin milk and the good stuff look the same until it's too late and it turns into a dairy disaster.

Things need to turn around real quick for the Honest Farmers.

If they can't find a way to catch the Cheaters, the dairy industry may never be the same.

[whistle blowing] Wisconsin Honest Farmers have called a time out.

Wait, will you look at that!

They're bringing out a new player, a true agricultural chemist from the University of Wisconsin, Stephen Babcock!

The original Dairy Dominator.

Not one for the spotlight, but don't let that fool you.

He has the skills to turn this whole game around.

This is a wise move by the dean, a legend in his own right.

Let's see what Babcock's first play will be.

He's got the line in an "I" formation.

Babcock appears to be looking for a method to separate the fat from the whey so people can know which is the better milk.

This play would be huge for the Honest Farmers, but seems like a Hail Mary.

How will he do it?

[flask bubbling] Babcock takes a flask of milk from sample A and readies his machine.

[crowd cheering] There's Sylvia, ready for the assist.

[cow mooing] What a dependable Jersey.

And it's off!

Babcock sets the play in motion Look at it spin!

Those puffy fat molecules are in for a heck of a ride.

There they go, separating right out of the liquid of the milk.

[crowd cheering] Spinning the milk reveals the cream.

Farmers can now tell the amount of butter fat in the milk.

There's no more hiding the thin milk now.

1st and 10, Wisconsin!

[marching band fanfare] But the game's not over yet.

There's still a little time left on the clock, and Babcock needs to move his team quick.

He has to make that same play for every type of dairy cow to clinch this game.

He better hurry.

The longer he waits, the worse it is getting out there for the Honest Farmers.

Fans are losing faith in dairy as we speak.

The clock is ticking.

Uh-oh, looks like the dean is calling for a hurry-up offense.

Babcock's not going to like that.

The dean is pushing Babcock to get his test out onto the field.

That's a risky move.

If Babcock's test isn't foolproof, those Cheaters could regain control of the game.

And with more dairies popping up in Wisconsin and across the globe, the results of this game are more important than ever.

Looks like the dean is giving Babcock one more shot to call the play.

Sylvia's the only cow left!

Can they do it?

Babcock is pulling out the stops.

He has all his tools in place.

Here comes the snap.

The machine is off!

It's spinning, spinning, spinning, spinning!

The cream is headed straight for the flask's end zone!

I can't believe it!

Babcock in for the score!

What an amazing play!

[marching band fanfare] [fireworks exploding] That is one for the history books.

The dairy industry will never be the same.

The crowd is going wild.

Babcock created a machine that efficiently and accurately finds the amount of butter fat in milk.

That play will forever be known as the Babcock test.

A true team player, Babcock works not for praise, but for the good of humanity.

[crowd cheering] But wow!

What a list of accomplishments!

Confidence in the dairy industry has been restored for years to come.

[upbeat folk music] [lively string music] [cheerful music] - Narrator: Have you ever flipped over a plastic bottle and seen a triangle with a number on the bottom?

That little number is a clue to the story of Milly Zantow, a Wisconsinite whose ingenuity and activism changed recycling all over the world.

When Milly heard that the landfill in Sauk County was going to close early, she was worried.

It was only five years old, and it was already almost full!

Even worse, toxic chemicals from the garbage were leaking into the ground.

What's more, another landfill might not be ready for years!

Where would all the garbage go?

[garbage falling] And why were people making so much trash in the first place?

So Milly went to the landfill and started investigating.

She noticed the trucks coming and going, dumping lots of things, but mostly, she noticed plastic.

Plastic, plastic, plastic!

Milly knew a bit about plastic-- how more and more things were being made with it, and how much of it was being used for packaging-- stuff that people were using just once, then throwing away!

She also knew that plastic would not decompose for a long, long time.

Hundreds of years!

Something needed to change.

Milly had grown up on a farm during the Great Depression.

Her family made good use of everything they had, and when something was used up or worn out, they repurposed it.

She was as thrifty as they came, and all this waste didn't make sense to her.

She knew some things were already being recycled.

Why not plastics?

Milly went to the county board and told them they should recycle the plastic waste going into the landfill, but they said they couldn't because they didn't know how.

She thought back to the plastic items she saw being dumped into the landfill.

Many of them were milk jugs.

So she called up a Milwaukee milk company with a question: [phone rings] - Milly: "What happens if there's a defect in a milk jug?"

- Manufacturer: "Well, we just melt down the jug and blow it again."

- Narrator: Milly also went to local plastics companies and asked if they could use recycled plastic to make their products.

They told her it wasn't that easy.

There were many different types of plastic mixed together in the garbage, but those different types couldn't be melted together to make something new.

The plastic waste needed to be sorted, cleaned, and ground up for companies to be able to use it.

And who was going to do that?

[whooshing] Milly knew what she had to do: save the landfills from overflowing and save the Earth by recycling plastic.

She went to the nearby university to learn how to do tests to tell the different types of plastic apart: Scratch tests!

- Milly: Oh!

- Narrator: Float tests!

[splash] - Milly: Ah-ha!

- Narrator: Burn tests!

[plastic burns and sizzles] - Milly: Oh!

- Narrator: Smoke tests!

[smoke poofs] - Milly: Ohh... [triumphant music] - Narrator: Milly also knew that she would need a way to grind all that plastic so it could be used.

- Milly: Hmm... - Narrator: She needed a big grinder, an expensive grinder, and more than that, she needed help.

She turned to her friend Jenny Ehl.

- Jenny: "Where are we going to get $5,000?"

- Milly: "Well, what about our life insurance?"

- Narrator: Milly and Jenny cashed in their policies, hopped in a truck, and drove to Chicago.

[gentle folk music] [truck horn beeps] They hauled their grinder back to Wisconsin and got to work.

They started E-Z Recycling in 1979.

Their business was all about making change in their community-- getting people to join them in a recycling revolution!

Even the students from nearby schools helped by collecting plastic items to be recycled.

Word kept spreading and soon spilled over into other communities.

The recycling revolution was growing!

[popping] But the work was hard, and much more than they could do themselves.

They knew they needed a better solution to make recycling something everyone could do.

The main thing was all that testing.

What if there was a way to tell the plastics apart without all that extra work?

They put their heads together and came up with a brilliant but simple idea: a number for each of the different types of plastic!

Manufacturers could stamp this number into the plastic so that anyone, anywhere could sort and recycle!

It took years of work for it to catch on, but they didn't give up.

Even after the numbering system started to get used around the world, Milly knew there was still more to do.

It wasn't just about adding a number to a bottle.

It was about changing people's beliefs and actions, and showing them how recycling would help people and the environment.

She helped with the writing of Wisconsin's recycling law and she kept talking with people about the importance of recycling everywhere she went.

By seeing a problem in her community and rallying people around her to find solutions at every turn, Milly changed Wisconsin and the world.

Milly's story is just the start.

There is still too much waste and not enough reusing and recycling, which means there are new opportunities for innovators just like you to help make the world better for everyone!

What do you notice in your community?

What will you do?

[wink] [upbeat folk music]

Support for PBS provided by:

Wisconsin Biographies is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

Timothy William Trout Education Fund, a gift of Monroe and Sandra Trout.