Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner-Charles Lytton

Season 4 Episode 7 | 27m 27sVideo has Closed Captions

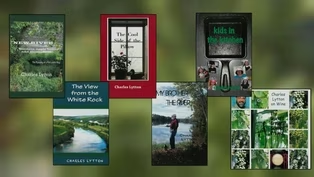

We'll talk about his books that are filled with stories of growing up on the New River.

In his words, this week's guest is a true Appalachian American specimen. We'll meet Charles Lytton and talk about his collection of books that are filled with stories of growing up on the New River.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Write Around the Corner is a local public television program presented by Blue Ridge/Appalachia VA

Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner-Charles Lytton

Season 4 Episode 7 | 27m 27sVideo has Closed Captions

In his words, this week's guest is a true Appalachian American specimen. We'll meet Charles Lytton and talk about his collection of books that are filled with stories of growing up on the New River.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[♪♪♪] -♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ [♪♪♪] -Welcome, I'm Rose Martin, and we are Write Around The Corner in Blacksburg with Appalachian author and storyteller, Charles Lytton.

And in his words, a true Appalachian American specimen.

We'll find out what he means about that in a minute.

His stories are filled with amazing renditions and things that he did in adventures growing up on the river, right here in Appalachia.

And you are in for a treat.

Charles, welcome to Write Around The Corner .

-Thank you very much.

-You have so many great stories filled in these books.

I can't wait to dig into some of these.

And I've got to tell you, after reading these books, Charles, like I told you before we started, and we'll get to that, I am really surprised that you are still alive, growing up.

But first of all, what is a true Appalachian American?

Why are you that great specimen?

-I think I'm a true Appalachian American because of the way I was raised.

My father and uncles, you know, kinda lived through the Depression, were drafted, went off into the Navy.

And all of 'em returned home.

And they were kinda dedicated to reliving the lifestyle they had.

So, though I didn't do the war, and didn't do the Depression, I got to experience what they saw.

And by that, I mean, you raised it, you ate it.

You created your own entertainment.

You did whatever your life threw at you.

And New River, for them, was kinda center of everything.

That, and a little 30-acre farm that they all lived on and kinda shared.

Appalachian lifestyle that you read about in a lot of books was just the lifestyle I lived.

-And it sounds like it was absolutely wonderful.

What are some of the first earliest memories?

-You know, we had, and there's houses on the river bottom now.

But the first memories were going to the river bottom to chop corn and hoe beans.

And my biggest dream, when I was a little boy that ever was, was to be able to run the two-horse wagon down the old road.

The old road that was used back during the Civil War to the river, to pull corn back to the house.

My uncle was telling me I'd never be old enough or comfortable enough to run the wagon to the river.

And by the time I was, the road was gone, cornfields were gone, and had to move on.

-Well, and I read in some of your books that you ate a lot of beans.

Lots and lots of beans.

In fact, didn't your dad had a little quote from your pinto beans out of the Bonnet book, on 193, which just was so poignant because it-- as we begin to talk about some of the great things that happened in your life.

Some of the things you did growing up on the river.

I thought this was pretty fun.

"Beans, beans, good for the liver.

"The more you eat, the more you shiver.

"The more you shiver, the more you shake.

It'll make you meaner than a rattlesnake."

And your dad would sing that.

-He'd sing it.

We ate beans all the time.

Green beans in the summer, brown beans all winter.

And then sometimes, you would mix green beans and brown beans together.

But you ate what you had.

-Well, and talking about that, it was really interesting to see the recipes that you've included in some of these books.

And I was reading the one about biscuits.

And I was really surprised of what you needed to make biscuits with just a can.

How did that work, Charles?

You do the whole biscuit with just a can.

-Mom had a 202 soup can that measured the volume of flour she needed and then she had holes in it to sift it.

You put the baking powder, baking soda, flour, salt and all.

You just sift it out the bottom.

We had things, don't get me wrong, but there was things you didn't have and what you didn't have, you improvised with.

But it even was the biscuit cutter.

It made a perfect 24 biscuits or 36 biscuits depending on what kinda cookie sheet or baking sheet she was gonna use that mornin'.

-And she did it every day?

-Every day of her life.

She got up at, I don't know, very early in the morning.

Made fresh homemade biscuits, every day.

-And there was something about the butter that was new for me, too.

The idea of yellow butter and winter butter.

-Well, see, in the winter, cows are eating hay, in my time.

You ate hay, and the butter was yellow in the summer because eating grass and lot of keratin.

But in the winter, it got real white, and yellow.

I mean, real white, not yellow.

-And so, it was much better tasting butter.

Was it sweeter?

-I think the yellow butter in the summer made your potatoes turn a whole lot better color.

And yellow butter will soak through your bread, and you can see it when you pour gravy on it.

That makes a lot of difference, too.

-As long as they're nice and warm, huh?

-Oh, my goodness, yeah.

-Okay.

So, what is it about a cast iron skillet that makes everything so much better?

-I think they conduct-- really, they just conduct heat very well.

And that's what grandparents had.

I mean-- -And you still have your mom's, right?

-Yeah, and that's kind of a neat story.

I've ended up with aluminum pans and all kind of different things when I went off to Rhode Island.

And I'm at my grandmother's house and Mom's one day, and I ask about the skillets.

And they'd thrown 'em all away.

Everybody bought new aluminum ones and stuff when they didn't need 'em anymore and turned 'em into dog water bowls.

So, I went around the hill and got all the dog water bowls.

Brought 'em home, cleaned 'em up, and I still use 'em today.

-I think that's wonderful.

And talking about tossing stuff over the hill, I was reading that oftentimes that recycling hadn't been thought about yet.

So, that's kinda what you did when you're done-- -Oh, I recycled those.

Still have 'em.

And for my little niece's wedding present, I gave her grandmother's cast iron frying pan.

And it had been in the family in 50 years or more and cooked a half a million eggs.

But it will live on, too.

-Yeah.

And I love the way you did your recipes.

Here's what you need and here's what you're gonna do.

And then here's a little bit of somethin', just for the cooks.

-Yeah, and just as an aside from that, I had a man calling from Ohio and wanted me to send him other books, but he said don't send any more of that green one.

Said he was now taking high cholesterol medicine just from reading it.

So, I mean, but we lived on butter, lard, bacon grease.

I've got a cousin named Kevin that still keeps-- he's as bad as I am about keeping alive of the past, but he's got a little metal bowl on the back of his stove where he keeps all of his grease, in case he needs thickenin' in gravy.

-I remember that from my grandmother.

Saving the bacon grease and savin' it because there wasn't anything like it.

Well, what is it about your grandma's green bowl?

What's the story there?

-I still have that green bowl.

I don't know.

It was just something that it really came to me when I moved down the river.

Everybody cleaned out all their smoke houses, basements, back rooms, and shipped all the old trash down to my house, that cabin, for me to sort through.

And one thing was a little green bowl.

I still have it.

I take it to family reunions and still put coleslaw and stuff in it.

And aunts, there's only one of them left now, but they would pick it up and look at it and remember and tell stories about the bowl.

Like everybody else, she'd just get tired of things and threw it away.

And when it got thrown to me, I just kept it.

-Hmm.

-It's got a million stories.

-I bet.

-And a million foods that have been in it.

-And it's a treasure.

It's just something that's-- -To me, it is.

-Yeah, it's a treasure.

And it's that time that you're remembering back when the river captured you and you were doing, you know, doing some amazing things.

So, I want to-- let's go way back to fourth grade.

Something that was really interesting, Charles, that I read in your book.

You said, "Gosh.

As a fourth grader, I'm tender and loving."

And this is out of your My Brother the River book.

"I was a seasoned well-driller.

"I had already been working our machines "for nearly two years.

"I would cuss and smoke cigarettes "with the best of 'em, and sneak a little nip once in a while, too."

When I think of fourth graders at 10 or 11, not only not being able to work on machinery, but the life experience you've had with growing up and then you say two years earlier, you had started.

Which would've meant you were like eight years old.

-Very early.

In the early days, my job was just carrying wood.

These well-drilling machines, or the one I worked on, was an old impact well driller.

It had a one-ton bit.

You picked it up one foot and dropped, up and drop, and it took months to dig a well.

And when you put it in the winter time, you just put this barrel out there, and you'd work a few minutes holding the cable.

You knew when to let it down by the vibrations of the cable.

I just carried wood to keep the fire going.

-And then, was it just a couple years later that you went over and started working in the mine, the coal mine?

-Daddy said to me one day, you gotta learn to work.

-And how old were you?

-Well, I was 12, 13, 14, but I was big.

And my Uncle Shorty and Nelson and Gilbert Hilton ran a little vein coal mine.

My name's chipped on the marble monument down at Long Shop for being a coal miner.

But anyway, the mine was what they called working a heading in a little vein.

It had a. I don't know, 18-inch seam of coal.

But the overburden made it four or five feet.

So, when you got it all cleaned out, you could walk but bent over.

And my job was to load the coal car and push the coal cars out of the mountain.

And-- -But you also delivered the coal, right?

-Uncle Shorty had this old international pick-up, and I was, like I said, big for my age.

I drove the truck to deliver coal and shovel it into the basement of people's houses.

And stop by different places and bring back jars of clean-- and white liquor.

And I always stop by another store on the way and got me a big double cola.

They was bigger and cheaper, so that's what I'd bring-- -They were cheaper at another store?

-Oh, yeah.

An RC was a 12-ounce.

And it would cost you 12 cents, 15 cents.

But you could get a 16-ounce RC for 12 cents.

And-- -Well, and, I loved one of the stories you put in here about you loved it when your-- when Daddy was hungry because you'd stop at the store.

And he'd get those colas and come outside with a big box.

And what was in that box?

-He'd come out with oatmeal cookies.

It had a big thick layer of that white stuff in the middle.

And you'd stop at the spring branch.

And you'd set your Coke or your big double cola down in that cold water and you'd set it in it, too.

And he would cut a big hunk of cheese.

I don't mean a slice, but a hunk, and you'd put it into your oatmeal cookie and eat it.

My sister will eat it, to this day, still talks about eating that oatmeal cookies or oatmeal cakes with that big hunk of cheese in it.

Yellow longhorn cheese.

-And it was a little bit of a sentimentality, you know.

Because some of the things weren't always easy with your dad.

Having a little bit of PTSD maybe, they didn't know what it was then.

-No, they didn't.

-Coming out of World War II.

-Daddy was a good sort, good heart.

But he did, he had a grumpy streak.

And he had a streak where he could drink a little extra.

But then I can get grumpy myself and drink a little extra.

So, I guess the older I've gotten, the more I've understood that.

-Well, and what a lesson to learn.

So, when I was reading the section on Moonshine, so first of all, coding of Moonshine X, XX, or XXX, it makes a difference.

-Oh, yeah.

X is one run through the steel.

It's a little tin, a little coarse.

XX, the proof liquor's gone through a second time and refined a little more, and XXX has gone through three times.

And it's maybe your best and cleanest alcohol, but it has a little less flavor, I think.

-Okay.

And well, and you might know 'cause I know you said that with a clean glass of spring water.

That's when it's good.

-Hmm, good.

-That's what's good.

Well, and something else.

Why did, when someone was going to get moonshine that both people would shake the jar?

-You shake a jar to test the proof.

-And it had something to do with the bubbles?

-You got to rake-- make a circle.

One, two, three and stop, one, two, three, and bubbles on high proof are big or larger.

And by the time of count of three, they're gone.

-But there were some interesting cures that you came up with when you had a little too much of that white liquor, with the pickles and the stuff in the cellar?

-We had a good size cellar at Grandmother's.

And Uncle Nelson, Daddy and Uncle Shorty all put stuff in the cellar.

But one thing we did as a family is, you made 55 gallons of sauerkraut.

And in that sauerkraut, you'd take 'em ole big pickle cucumbers that were so big you couldn't eat, and cut 'em into quarters.

And put 'em in there and salt brine pickles.

Golly!

-The look on your face now is saying you can remember clear as day.

-People would come up there with hangovers and take and run your arm down in that water, that scummy water, and get out a couple of 'em old cucumbers or pickles and set on the cistern cover and eat 'em things, and drink water out of the pump.

I mean, the salt would make you drink water and that, I guess, was the real cure, but I've seen 'em.

Hmm.

-And it was interesting that you put an unbroken egg in to see if you needed more salt.

-You got to float it.

-So, I'd never heard of that.

But what was--?

-Oh, yeah.

-So, what did that show you?

-It showed you if the egg sinks, you need to work more salt in.

If the egg floats clear, or floats clear up on to the top, you got enough salt to keep it from spoiling.

-Okay.

So, look at all the stuff I'm learning now, right, Charles?

-And you don't put water in this.

You chop the cabbage up and put salt on and work it with your hands until it's runny and scoot it off in a bucket and dump it in the barrow.

And then you lay boards on top of it and put rocks and mash the cabbage down until that cabbage juice comes up on top.

-And that's where the egg would-- you wanted the egg to float.

-Yeah.

And that I know did-- for good details on because again, my cousin Kevin, still makes many jars of homemade sauerkraut.

It's so salty that you eat it and just run to the water fountain.

-Hmm, hmm.

So, let's pivot a little bit to the river.

So, I put together all of these things, Charles, that I thought might be accidents.

So, you were electrocuted on the top of a telephone booth.

You started a maple tree business with balsam wood trees.

-I did that.

-And then you drank it.

You went over the handles of a few bicycles in your time.

-I've wrecked more times than-- -You had the jackhammer incident with your head and your teeth.

You had an incident with a gas stove where you and your buddy started a fire that you put out with your hand.

You were pulled to the bottom of a coal car.

You were chopping a hole in ice for cows and horses to drink, and you slid up and had another concussion.

Charles, and then rock diving?

Wow, Charles!

-My sister, Lita, all of us did that.

You'd run across the river from the bus.

The river's too high to do it much now.

But there's a ledge right in front of the bus.

It's about two feet down, in our time.

Now it's four feet down.

And you'd set on that ledge and drink beer.

But you could go over to the arsenal side and get you a rock about yay big.

And you'd go back to where that low ledge is.

You hold that rock and just step off and you'd plunge down until you got to your head-- -Oh, your poor mother.

-No.

To your head would just split.

And you'd drop that rock and come, whew, back up.

We thought it was fun.

We didn't know we was gonna be drowned.

-Yeah, well, and then, how about being electrocuted on top of the telephone booth?

-My dad had a part-time job installing telephone booths.

And I'm up on top of the booth wiring up the light.

And Dad is in the-- I can't think of the name of the store up on Crater Lake.

And he flips the on switch, and it just made spark fly off my teeth and knocked me off the booth.

Dad said, "I'll never get done here if you keep wallowing around on the ground."

Didn't-- -Get up and get back to work.

-He didn't-- none of the Lytton men, none of my uncles had much compassion for stuff.

They didn't understand that you could get hurt, and it may hurt you.

My cousin Kevin talks about the time his granddaddy chopped the end of his toe off with a mattock digging potatoes and told him, "Now, look what you've done."

-As if it was his fault.

-Yeah.

All of us have those stories of my father and my uncles.

-But with all of the books that you have and there's quite a collection here, why did you decide to memorialize these stories or put them all in books?

[Charles] It's very funny that you ask that question.

Two things happened about the same time.

One, I retired, and I'd laid around the house a couple of weeks, didn't haven't anything else to do.

And my sister was very sick, and we had a little get together for her and all of the family over here like a little mini reunion.

And we asked people to write 'em a little story about living on the ridge, and come and just tell that little story.

And I started off writing this little story about the first time I rode a sled that wasn't a sled down over the hill to the river.

And before you know it, I had like 175 pages of stuff.

And after we finished that little get together, I shared it with Joey Huffman, a lady who writes in Giles County.

And Joey liked it and said I need to talk to Rachel Garrity.

Well, I go to Joey's house to pick up the book, and it's in her trash can.

-Ooh.

Ouch.

-I said, "Good gravy, I know what you think."

She said, "No, no."

She pulled the bag out of the trash can, and it was taped to the inside of the trash can.

She said, "There's people round here steal your stories."

And when Joey is a successful writer and if she's hidden my stories in the bottom of her trash can, I may talk to Rachel and see what happens.

And the first two books came out of that stack.

And, well, I've had fun writing 'em ever since.

-What's the process like for you to put the stories down on paper and then to get them published?

-I laugh about this still, the green book, New River: Bonnets, Apple Butter and Moonshine, when it was published.

I thought, "Well, I want a copy."

And my mother'll want a copy.

And I went through the family and had ten that I knew I could give away, so I ordered 12.

-Two extras just for spares.

-And I go up and down the road hollering, "I did it.

I did it."

And you know, it was like, I don't know, sugar wasn't licked all the way off that sucker.

And I just enjoyed it so much.

And since then, I've just, every once in a while, kept going.

-I love one of the things you said about the river.

"River Ridge and the waters "have a kind of healing power on their own.

"And always keep in mind that the old slow New River, "when she wants to, can come up very fast, "wash away houses and animals, and destroy everything in her path."

-It does.

-So, there's that respect for the river, too, as much as you're drawn by listening to the sound of her.

-We were up in the Radford Arsenal fishing two weeks ago.

And as much as 30 feet up, there's trash hung in the trees.

So, I mean, a few weeks ago, when we had the big floods, or months ago now, there was 30 feet of water coming down river.

And now it's just as flat as a pancake, but a few weeks ago, it wasn't.

-And you said something about sleeping outside.

You love to be in the outside bed when you had that bus down on the river.

And why was that so important?

-I don't know.

We had this old school bus.

I moved into a school bus and lived in that thing from about age 10 until I bought the cabin further down the river.

But I lived in it all summer.

And outside, we had this old metal bed frame with a set of box springs on it.

You just put a mattress on it, and you went to sleep.

And it was cool.

It was comfortable.

The river would flow by.

You could see the stars.

You could hear the fish jump.

You could fight mosquitoes.

I mean, it was just-- -Sounds amazing.

-It was a different-- I don't know, upbringing.

-Would you be willing to read something for us?

-If you tell me to, I'll try.

-I would love that.

-I'm the world's worst reader I ever met.

-Well, let's go ahead and give it a shot.

-All right.

Like I said, when I was a kid, I was turned lose.

And I mean, I think that parents today would just have a heart attack at how free we were.

-That's what I told you when I read your stuff.

-And I mean.

The old paddle.

"Let me tell you about the big riffle at Lover's Leap.

"This is a place where the river grew narrow "and the water got moving real fast.

"One of my most impressive river boat skills "was exhibited at this very riffle.

"For a while, this feat of true river skills "was talked about up and down the road at the old stores.

"Well, I talked about it a lot, at least.

"Some of the old men listened; some didn't.

"I still liked the story, and I still do.

"Often, men would come up, bring their boat up "to the old big riffle and struggle.

"They'd get out of the boat and paddle it up through, "but I could paddle a boat up through the riffle.

"Once Daddy and I were at Bird Shepherd's sawmill, "and he spied a piece of Poplar lumber "two inches thick, ten inches wide and a foot long.

"It wasn't a flaw in that board anywhere.

"We brought it home "and went over to Mr. Luther Schneider's house.

"Mr. Luther was a wood worker of great renown, "and together we cut out a perfect boat paddle.

"What made this one so special was "it had a three-foot blade and a handle so long "that it required the operator to stand up in the boat, "not set down to use it.

"'Why, no one but you would want such a thing.

"A paddle like this would kill an ordinary man dead,' "and Mr. Schneider laughed.

"If you put your heart into working this paddle, "you could move mountains.

"In other words, if you was tough enough to stay with it, "you could paddle up through Lover's Leap riffle.

"I learned that all you had to do "was come into that riffle from the Radford Arsenal side "and kinda keep to the shallows of the river, "and you could paddle through it.

"My heart would beat fast afterwards, "but that was okay.

I could rest later.

"I was on my way to the burning ground "and them big flat rocks with the deep channels.

"The Radford Arsenal people had stretched a big cable "across the river to mark the boundary "between public river and government river.

"The government was very picky about what they owned, "and they let you know it.

"I was still too young to vote "so I did not holler back at them too awful much "when they ran me out.

"For the most part, a fella could not pass the cable.

"Sometimes, the arsenal guard would let me pass "and paddle up river to the burning ground.

"Sometimes, he would holler at me "and tell me I'd gone far enough.

"Other times, I would just pass the guard tower "and never hear a word.

"That arsenal guard rascal wasn't in the guard house "all the time.

He had to sleep sometimes, "he had to go home once in a while, "and I knew this.

"Yes, I was a slow learner, but I was consistent.

"You almost had to try for it every day "to catch a guard off duty.

"It was worth it because there were real good fishing "up river beyond the cable.

"Plus, after paddling upwards of two miles "against the current with the big paddle, "I thought I needed to fish upstream "as a kind of a reward or something.

"I would sneak past the cable, "and I felt like I was a part of the story I'd once read "about the Big Two-Hearted River by Ernest Hemingway.

"In my life, there was no greater feeling "than to paddle above Lover's Leap after midnight-- "after the midnight whistle had sounded at the arsenal.

"Everybody from miles around would be asleep except me.

"I have shared this adventure with other people in the past.

"They've looked at me like they thought "they were hearing some kind of tall tale.

"I think they must've lived an awful bland youth.

"The night air was almost always cool and clean.

"Often, the stars would be very clear and bright, too.

"Never was there ever another person on the river.

"I paddled to Lover's Leap, "stripped off my clothes and jumped in the river "and swam and floated behind the boat.

"I worked my way back to the bus or the cabin.

"There was no sound but the sound of the water "slapping up against the boat, "and an occasional fish jumping.

"Once in a while, "when a loud coal train would come up the mountain, "you could even feel the vibrations in the water.

"There was no other way to express it.

"The river was good to me, "and it seemed like it had a lot to offer.

"Man, I was free.

I was always free when I was on the river."

-That was just beautiful.

I'm so sorry that we're out of time.

Thank you for joining me to be here today for Write Around The Corner .

And I think I love this, Charles.

In your words, "You've run fast and far.

"You've eaten some great stuff and drunk some fine wines "and white liquor, too.

"I've done all of this old body could ever want.

"Once the river gets her hands on you, "she never does seem to turn you lose.

"For me, I don't think there's a clear line between "the New River, River Ridge, and any other place on earth.

I was just born lucky."

And I agree.

Charles, we're the lucky ones.

-Thank you very much for letting me do this.

Chuck Shorter summed it up the other day.

He said, "You know, me and you is stove up now-- -Stove up.

-But man, we've had a good run.

-Thank you so much.

And thank you so much to Charles Lytton for sharing the stories of growing up on the river in Appalachia.

And to all of you for taking the time to spend some time with us.

I'm gonna be getting with Charles for more stories.

So, make sure to check us out online and tell your friends about us.

I'm Rose Martin, and I'll see you next time Write Around The Corner .

[♪♪♪] -♪ Every day every day Every day every day every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ ♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ ♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪

A continued conversation with Charles Lytton

Clip: S4 Ep7 | 16m 35s | Hear more stories , plus learn about his wine book and his plan for future books. (16m 35s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Write Around the Corner is a local public television program presented by Blue Ridge/Appalachia VA