Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner-Rita Sims Quillen

Season 4 Episode 8 | 28m 6sVideo has Closed Captions

Learn about moving stories of love, trauma & history that take place in 1930s Appalachia.

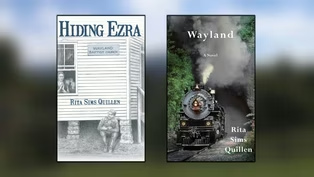

The mountains of Scott County are the backdrop for two novels and our interview with author, Rita Sims Quillen. Hiding Ezra and Wayland, are moving stories of love, trauma and history that take place in 1930s Appalachia.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Write Around the Corner is a local public television program presented by Blue Ridge/Appalachia VA

Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner-Rita Sims Quillen

Season 4 Episode 8 | 28m 6sVideo has Closed Captions

The mountains of Scott County are the backdrop for two novels and our interview with author, Rita Sims Quillen. Hiding Ezra and Wayland, are moving stories of love, trauma and history that take place in 1930s Appalachia.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[♪♪♪] -♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ [♪♪♪] -Welcome, I'm Rose Martin, and we are Write Around The Corner in beautiful Scott County.

We're here with Rita Quillen.

Do you know her from her poetry books?

Well, today, we're gonna be taking about two novels, Hiding Ezra and Wayland.

Think about 1930s Appalachia.

Rita takes us on a journey of love and trauma, and suspense.

And of course, there's a pandemic as we're socially distanced here during our pandemic.

And just when you think you're feeling a little bit better, a stranger comes to town.

And you know what?

Things will never ever be the same.

Rita, thank you for joining us for Write Around The Corner .

-Thank you for having me.

Thank you both for coming all this long way to visit me at the farm.

I'm happy to get a chance to meet you.

-Well, this is a little piece of God's Country out here.

-[Rita] Oh, yes.

-It is breathtakingly beautiful.

-Thank you.

We love it here.

-And how long have you lived out this direction?

-We've lived here about 20 years.

-It's absolutely beautiful.

I guess this is a great place to write.

-Absolutely.

-[Rose] Lots of creativity.

-Absolutely.

It's quiet.

There's not any other noise other than the birds and the wind, and I love it.

So, it's been a wonderful, very creative place for me.

-Did you grow up in the area?

-Actually, just over that mountain.

Right over there.

I grew up in Hilton, Virginia, which is near where the Carter Family's from, that part of the county.

But yeah, my family has been here in Scott County for about five generations.

So, we just moved over the mountain.

-Well, and I love the fact that not only are you an amazing poet and finalist for the Poet Laureate of Virginia, you're a beautiful writer.

And that poetic license, that comes through in your writing.

We'll talk about that a little later.

But you're also an accomplished musician and songwriter.

-Well, I wouldn't call me accomplished, but I am a musician and a songwriter.

But I tell people more, I claim the title of music lover rather than musician.

My brother was actually an amazing musician.

I come from a very musical family, but I can play at a lot of different instruments.

I can play 'em a little bit.

I love mountain music, and I love to get a chance to get together with people and play.

And I have written some songs, but they've all come straight from my poems.

And I had never done that before until about five or six years ago when I wrote the book called The Mad Farmer's Wife .

I began to hear those poems as songs and eventually translated some of those over, and it's been a lot of fun.

-But you also lend your singing voice to those songs, too.

-Yes.

You can see that on my website if you'd like to hear some of those.

So, yeah.

-They're beautiful.

-Thank you.

-I had to check it out a little bit ahead of time.

Do check it out.

-Thank you.

-So, you live out here with your husband and your two children.

Are they writers, musicians, artists?

-Oh, my children are very creative.

Particularly, my son.

My son is a writer and a filmmaker.

My daughter is a wonderful writer as well, but she works in education.

She and her husband work up at Washington and Lee University in Lexington.

So.

-And you had 30 years, just recently retired as a teacher in the community college system?

-Thirty plus, yes.

I taught about half of my career in a community college over in Northeast Tennessee.

And then I finished up the last half at Mountain Empire Community College in Big Stone Gap.

-So, think about as a child, what are some of those memories that you had growing up in this beautiful location that you think led into some of your poems or some of the books we're gonna talk about today?

-Um.

well, I tell people that I think I would've been a writer, no matter where I lived or grew up, if that's sort of who you are.

It's the kind of brain that you have.

But the Appalachian Mountains, people here are storytellers.

There's a kind of magic to the way they talk.

And so, I remember even as a little kid, noticing how people told stories, just in everyday conversation, and paying attention to that.

The other big influence on me was the language of church.

The Bible and the hymnal, to me, even as a little bitty kid, I realized that that language was different from language I heard anywhere else.

And I began to really pay attention to that and to learn that vocabulary and to listen to the rhythm of, for example, the Psalms.

And even as a little kid, I can remember doing that, being struck by it.

So, I think just being in a world where words and the sound of words, and the music of words was very valued, definitely came into play.

-When you mentioned storytelling, it made me think-- you said something about the way they tell the stories.

And then you moved into kinda the lyricism of music.

Is there a parallel there, do you think?

-Oh, absolutely.

There's a rhythm to storytelling.

Just like-- and there's a way of building toward a climax, which you learn in songwriting, too.

Thinking about those little tag phrases that build the suspense of the song or help carry the story through.

And at the same time, paying attention to how many beats, and, you know, what the sounds are in the line.

And the really best storytellers are also wonderful phrase makers, you know.

And I noticed that, even as a child, that a lot of the people that were so popular in the community were these gifted talkers.

And they just had a way with words that was a little elevated from just regular conversation.

And people were just held in rapt attention when they talked, you know.

So, it's just paying attention to the power of words.

And I feel like living here, where that, for some reason, is part of our culture, was a very good influence on me as a writer.

-Well, and you can hear even having the space.

I love the pacing of the storytelling.

Because it's not rushed, and it's so authentic.

And you've done a lot of work in the Appalachian language, in the Appalachian voices.

And actually, didn't you use a textbook that you had edited partly in your courses that you worked with in school?

-I helped edit a textbook that featured Appalachian writers and the history of Appalachia and Appalachian dialect.

It's just called a Southern Appalachian Reader , and then I've been part of other books.

Now, a section of Hiding Ezra was actually featured in an academic book called Talking Appalachian , which came out from the University of Kentucky Press.

And that's what that book was about, was about how that spoken language and storytelling and poetry was such a part of our linguistic heritage here in the mountains that it made our speech distinctive.

Not just because of the way we pronounce our vowels, but just the way we tell stories and the way we talk and banter is a little different here.

And so, that's a really fine book if you're interested in the subject of dialect and speech.

I highly recommend that one.

-Well, and I read somewhere that you had decided by the fourth grade, that you were just absolutely gonna be a writer and told your teacher.

What's that story?

-Well, just I loved, loved books.

And I went to Hilton Elementary School at that time was a tiny little school.

Our library was about the size of, I don't know, one room, a regular size room in a house.

You know, like, I don't know, 10 x 12 or something.

And by the time I was in the fourth grade, I had read most of the books that were in it.

And I thought, this is the greatest thing ever.

When I grow up, I want to write books.

So, I asked for a typewriter for Christmas in the fourth grade, and I taught myself to type.

So, I said, "Well, you know, that's the first skill I've got to acquire, I know."

-[Rose] Right.

-So, yeah, I just always knew that writing was something I loved.

And I was already writing some songs and things when I was in fourth grade, little poems and stuff like that.

But, yeah, it was always something I knew that I loved to do.

-But there was an important lesson because I read somewhere that, you know, you had this idea that a writer had to be something exotic and magical.

And it really wasn't about that.

What's that lesson?

-Well, I just, I think when you're young, you have this idea of writers as being some glamorous thing, and they all have to live in New York.

And they write about, I don't know, the world.

They have to be, you know, these very sophisticated world travelers or something.

And it took me growing up to realize that what writers write about is their place.

They drill down deep to their own lives and their family's lives and the very place where they lived and put down roots.

And learning to have enough confidence in myself to know that those stories were what I needed to tell.

Of my family, my life, my community, my culture.

And to be self-confident enough to say that I'm gonna do that even though the world may not pay much attention.

I don't know if I'll ever get published or anybody will care about any of this.

But I'm gonna try to tell these stories of this place.

That took awhile to get there.

-It's like the unique beauty of the location and the people.

But I read somewhere that you had said that you have this beautiful great love of the mountains and the people, but you grew up in a place that was embarrassed by itself.

What does that mean?

-Well, I think there's an inferiority complex, I think, a little bit among mountain people.

I mean, let's be honest, if you look at sort of popular culture, there's all these stereotypes that are very negative of mountain people.

And there's, you know, the Snuffy Smith and The Beverly Hillbillies and all of those kind of pop culture images are of these people who are, you know, uneducated, backward, nalïve, unsophisticated, dirty.

There's all these terrible, terrible stereotypes.

And so, trying to think, how do I present those people in a different light?

And how do I present myself in a different light?

While I'm still that person, I'm still from the mountains, but I'm not that stereotype.

And I don't wanna do anything to perpetuate that in my writing or in anything that I do.

I want people to see the good side and the positive side.

And the fact that those stereotypes, while there's always a grain of truth in any stereotype, that they're way overblown.

And that the people in the mountains are like people everywhere else.

They're universal.

-And I think it'd be fair to say a lot of people get it wrong, you know, where they get it wrong.

But what can we do in order to get those perceptions and get those stereotypes shifted?

-Well, I would certainly like to see sort of the pop culture gatekeepers move on.

I mean, I wish they would tell stories like Hiding Ezra rather than Snuffy Smith , you know, and The Beverly Hillbillies .

I want 'em to take real people, real lives, from the mountains and tell those stories and that show people in their full humanity.

You know, all of the dark and the light and the complex layers that they have.

And that they're no different from people anywhere else except for this beautiful setting.

And maybe our speech sounds a little different, but other than that, it's just about being human and all the struggles that that entails.

And I wish that pop culture, so to speak, would stop reinforcing so many of those negative stereotypes and just sort of fallin' back into those easy stereotypes.

-It's like people are a lot more alike than they're different.

Their settings and where they were raised.

Those things, those things vary.

-Right.

-Hmm.

So, when we think about the process of you going from poetry to novels, was that a tough transition or pretty seamless?

-Oh, it was terribly hard for me.

Poetry is something that comes naturally to me.

That's my first love.

I'm a very-- I have to say in some ways as far as poetry, I'm a very undisciplined writer.

I'm what I call an inspirational writer or a mystical writer.

These poems come into my head.

I recognize my poet voice.

And when a line comes to me, I know it's a poem.

And I run then and sit down and see what's gonna come.

With fiction, it's all about self-discipline and routine.

You've got to work every day, so many hours in the chair.

Some days, you get a lot done; some days are absolutely frustrating, and very little gets written.

You just sit in the chair.

But that's what you have to do.

I always tell people it's the difference between right brain and left brain.

You know, poetry is right brained, and I can do that easily.

Fiction is left brained, and it requires discipline and a lot, lot, lot more time and research.

So, it was a struggle.

But it was very satisfying, too.

It was something I'd always wanted to do was to write novels, so.

-Well, and they're beautifully written, and you can hear your poetic voice all the way through the novels.

When you had mentioned doing research, there's a section we're in the '30s.

We're in Appalachia.

We've got the pandemic, which is appropriate as we're doing this during the pandemic right now, socially distanced.

But there's a big section on the hoboes and the communities and, you know, which the hoboes lived.

Were there a lot of 'em in this region?

Was that a--?

-Yeah, there were quite a few.

There was a.

Everything in the book is true as far as I know, based on my research.

There was a large-- it was called a jungle.

There was a hobo encampment in Gate City.

It was down along the creek there that runs.

what they called the Back Street.

Where old Daugherty Brothers Chevrolet used to be in Gate City was the hobo jungle.

And most every railroad town had a jungle of some size.

And.

really, the whole country, during that time period, was full of hoboes.

I did not realize until I read the Studs Terkel's study of the hobo community and their history, how many of them there were and how widespread it was.

But, yeah, there was a-- because this was a pretty vital railroad link between the coal fields, then into the industrialized towns of Kingsport and then on over to Asheville and places, the hoboes were pretty active through here.

There were quite a few of them.

And I've met people-- in talking about Wayland to people, I have met people who said, "Oh, yes.

My mother took care of a hobo.

My mother would feed the hoboes" and all of that.

So, it was evidently pretty widespread.

-And true then, I'm guessing, that the marks on the trees was actually true to where they were messages to other people.

-Yes.

The hobo sign language, the Hobo Nickels, the, what they called tramp art, was amazing.

The Hobo College, all of that is real.

All of that really happened.

And in the last summer, I had the opportunity to actually go out.

There is a National Hobo Museum and festival.

It's held every year in Britt, Iowa.

And I went out there last summer and got to visit the museum and meet those people who put that on.

And they're still active.

What is astonishing to me is that there is still a fairly active hobo community.

That is a way of life, like the gypsies.

And they are still very active out in the Midwest and all out through the west.

And every year when they have that hobo festival, well, they have like a 100,000 people show up, including several thousand hoboes, who come and gather there in Britt and be together and tell people about their lifestyle.

So, yeah, it's still going on very much.

Wherever there's railroads, there are hoboes.

-You're gonna see that.

You know, another thing that struck me was how you used the journal entries as a way to add so much richness to the story.

So, obviously I'm curious, do you keep a journal?

-I do not.

But how that got started was, you know, the Hiding Ezra story is a true story based on my husband's grandfather.

And he kept a journal, and I've actually seen it.

When I was working on the novel, I actually got a chance to see the journal.

And so instantly, I realized that was a treasure trove, that that would be a beautiful way to let you get to know that character more deeply would be through his journal.

And so, when I started Wayland then, I thought, "Well, I wanna do the same thing with this character."

Because I agree with you, I loved the way the journal turned out.

That it gave you an insight into the characters that allowed me to go so much deeper and lets you hear that voice, to hear that idea of the talking again.

I wanted you to have that idea of how we talk.

And both of them write the way they talk.

So, that was the fun part of it for me was bringing that voice alive on the page.

-The other thing that I absolutely loved was the way you put these one-line zingers.

sprinkled them all the way through.

Now, was that that literary, that poem voice that said, "I just need something to tie this section together."

-I think so, yeah.

Obviously, with poetry, it's all about one line at a time.

And hearing that line that's that perfect attention getter, whatever it is.

So, yeah.

I would say definitely the journals are the place where I felt my poet voice would come into play the most was in the journal.

-I love this one line, I've got to just say.

This is on page 86.

"Dad always said, it's better to keep quiet and be thought of as a fool, than to open your mouth and remove all doubt."

I'm like, "Ooh.

Okay."

-That's actually an old mountain sayin'.

I've heard that all my life, yeah.

And it's very true.

There's lots of those little nuggets like that.

Again, that's part of that verbal inheritance that I have.

From the way people talk around here, there's a lot of old-- always my husband calls them hillside philosophers, you know, and there are a lot of 'em.

-I like that, the hillside philosophers.

-Yeah, they're just-- they're people who are thoughtful, and like I said, they have a way with words.

And I grew up in that and just thought nothing of it.

I didn't realize until I was much older how unique that way of talking and thinking was, you know.

-Well, in Hiding Ezra , you got me at the very opening of that book because without giving things away, as people begin to open the book, you actually know that something's going on, but you grab us, the fact that we're laying on the dirt, you know.

We can hear the church, what's happening in the church and know that you're taking us on an amazing journey.

So, let's dive into Hiding Ezra a little bit.

You've got a few main characters.

Who are they?

[Rita] Well, Ezra is based on the life of my husband's grandfather.

During World War I, he was drafted, as most young men were, during that war.

He went up to Fort Lee, started basic training, and then they sent word that his mother was extremely ill. She was dying.

So, he came home to check on her.

She extracted a deathbed promise from him that he would not return to the military.

That he would stay and take care of their father, her husband, who was also very ill.

So, he made her a deathbed promise, and that was it.

He decided he wasn't going back to the war.

And in his naiveté, he thought he could just go to the military and say, "Well, you know, my parents are sick, and I need to not do this."

But that didn't work.

So, he found himself unwittingly an outlaw.

And so, the story is about his life on the run.

It opens with the scene of something that really happened.

He would go to church, every Sunday, by crawling under the church and lying under it and listening to the service.

And they had no idea he was there.

So, the story is of his adventures, of his girlfriend, Alma, the woman he loves, who tries to rescue him from this mess.

And this man named Andrew Nettles, who's a young man from Big Stone Gap, a career military man who chased him for all that time for two years.

And all of the other deserters as well, there were a quite a few of them here in Southwest Virginia.

So, the story is about-- it's an adventure story.

It's an outlaw story.

It's a love story.

There's a lot of things wound together, but mostly, it was a chance for me to try to get my husband's grandfather's amazing story on paper, and to make it make sense.

When they told me this story, there were things about the story that didn't make sense, to begin with.

So, that's why it took me so long to do the research, to figure out how it all would've played out.

-But you didn't end it there.

You followed up with Wayland .

[Rita] Right.

-And you introduce us to an absolutely diabolical evil.

Someone that when I did in the opening for the show like, "Uh-oh, you know, life is never gonna be the same."

Was that always a thought to have Wayland as a second piece with the additional characters?

-No, I didn't.

I wanted to do another book, but I had no idea what it would be until it just hit me one day.

What would I like to do as a writer that I have never done before?

And I thought, one of the things that fascinates me, because I love crime shows and crime TV, I'm one of those people.

How about I do a study of evil?

I mean, a truly psychopathic, evil, manipulative, dangerous predator.

Who comes into a place like Scott County, where people are so kind, and they're all good Christian people.

And they're trusting and loving, and this man, what's he gonna do?

He's gonna be a predator.

He's a sexual predator.

And I wanted to do a book that had some kind of, I hoped, purpose it might serve.

My dream is that somewhere out there, there's a mom or a dad or a grandma or grandpa, who reads that book and all of sudden goes, "Oh my goodness."

And they realize that their child and their family is being groomed, that's what it's called, grooming, by a sexual predator, and they wake up before it's too late.

-Well, and you build the tension from him without knowing what his bad characteristics are.

So, I found myself doing it in one sitting, just because of that, to build up the tension of, gosh, these people are so kind, and they're so nice.

And why on earth did she write this crazy hobo coming in to just take advantage?

I was really happy with the way this story was going all on its own, and everything was really good right then.

And it's interesting, you know, you bring in the multigenerational issues with the characters, the parents, the kids, the heartbreak, the war, the pandemic, the health issues.

Beautifully, you know, beautifully written to where I'm right there with you in the story to where I feel like I'm a part of it.

Would you be willing to read something for us?

-Yeah.

What would you like for me to read?

-Well, why don't you pick a section out of Wayland ?

-Okay.

I can do that.

Well, I'm gonna read a little section at the beginning where you have just met Buddy.

He has come in to town on the train.

He's found a hobo jungle there.

And he realizes there's opportunities for him here.

So, I'll just give you this little introduction of him.

"In the Gate City jungle, there were tramps and hoboes, "and probably quite a few were like Buddy "and moved between both worlds.

"Meaning, sometimes they would work, "if they felt like it and it was fairly easy, "but if they didn't find an easy path, "they'd just steal, or run a scam.

"Because of a little group of nuns there, "the town attracted lots of his kind.

"The nuns had money and big hearts.

"What more could these struggling souls ask for?

"The camp was full of guys with a sad story to tell.

"One of them called himself Chicken Joe "and claimed to have a dying mother in North Carolina "he was trying to get home to see.

"Several claimed to have jobs waiting "down in Tennessee or Georgia, "if someone would just see fit to stake 'em money to get there.

"There was one 'dummie' pretending he couldn't hear or speak.

"But Buddy saw through him right away "when the man jumped and yelled at a big clap of thunder.

"Buddy laughed at the man and cussed him "and threatened to beat him to death while he slept.

"The man disappeared by the next morning.

"That wasn't the only problem though.

"A gang of tramps hung around, the kind who wouldn't work.

"What the wandering folks called a "push".

"It was a mixed gang.

"Some old, some young, and a nasty piece of work.

"A man appropriately named Iron Mike "ran the gang with an iron fist.

"The gang bragged about killing people, "mostly railroad bulls, "and other hoboes who crossed them.

"And Iron Mike was the sort of man Buddy knew "and hated with the white-hot passion "he could feel in his gut.

"The kind of man who thought he was invincible "and better than anybody else.

"Iron Mike had a young boy named Isaac with him, "who he protected from the others.

"And Buddy had seen Mike stroke the boy's hair "at the edge of the campfire light.

"The boy didn't seem to like it much, "and Buddy felt sick to his stomach for him.

"He'd have to see if he could think of a plan "to help that boy out.

"Gettin' away from the jungle "and from the stares of the good town folk "and the suspicion of the local sheriffs "seemed like a good idea.

"Buddy never liked towns or cities anyway.

"He felt uneasy and exposed.

"They had too many variables he couldn't control.

"Too many players, too many moving parts.

"No, he liked the county better for lots of reasons.

"That's why he'd headed out toward the back of the county.

"There were train depots if you needed to leave fast.

"But what really drew him "was the kind of people he'd find there.

"Good county people, innocent, god-fearing, "and hard working.

"Poor enough to have sympathy for someone like him, "but prosperous enough to have resources he could use.

"When he crossed Copper Creek "and started the long climb over the first big ridge, "he immediately felt rushes of cool air "that seemed to come up out of the ground.

"Sweet smells, wonderful quiet.

"He made sure he changed his face.

"In some of the big cities, "he'd make use of a more educated, "sophisticated face.

"And he used what he called the Professor look, "pretending to be an educated man, "a teacher, down on his luck.

"But here, he decided to go for his Country Boy look.

"He pressed the corner of his lips "into a perpetual little smile, a clown face.

"Opened his eyes much wider.

"Made sure to relax his brow.

"He worked on remembering to nod his head a little "every minute or two, "like he always agreed with what you were saying.

"He loved this character, "and it helped him in many a small town or wayside.

"He saw a sign on a church that read Wayland Baptist Church.

"'Wayland.'

"Buddy said it out loud to himself and smiled.

Wayland would show him the way to what he wanted."

-Hmm!

Rita, Rita, Rita.

You reading that again, I don't like him anymore the second time around-- -Well, good.

[Rose] --than I did the first time around.

-I've done my job, then.

So, I wanted him to be evil as Iago or Hannibal Lecter, and yet so appealing on the surface that he just charmed you.

You know, you have no idea-- -Your writing has charmed us.

It's absolutely beautiful.

-Thank you.

-And I hope you'll stick around.

-Thank you so much.

So, we'll have to talk a little bit more about your poetry.

Special thanks to Rita Quillen for inviting us to her beautiful farm here in Scott County, for sharing two amazing books with us, based on true family story journals, Hiding Ezra and Wayland.

You're definitely going to wanna make sure to get caught up in the story of Appalachia in the '30s.

Please make sure to join us online for our extended conversation with Rita.

We'll be talking about her poems.

We'll be talking a lot more about these books and the fascinating life that she has right here in Scott County.

Tell your friends about us.

I'd sure appreciate that.

I'm Rose Martin, and I'll see you next time Write Around The Corner .

[♪♪♪] -♪ Every day every day Ev ery day every day every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ ♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ ♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪

A continued conversation with Rita Sims Quillen

Clip: S4 Ep8 | 21m 39s | We'll hear fascinating stories behind Rita's books PLUS she's share her poetry with us. (21m 39s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Write Around the Corner is a local public television program presented by Blue Ridge/Appalachia VA