Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner - Robert Gipe

Season 5 Episode 10 | 28m 8sVideo has Closed Captions

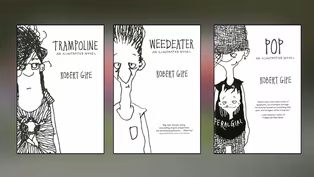

We talk with Robert Gipe about his innovative trilogy – Trampoline, Weedeater, and Pop.

This episode finds in Harlan, Kentucky, to talk with Robert Gipe about his innovative trilogy – Trampoline, Weedeater, and Pop. These illustrated novels introduce us to a cast of characters and a range of issues in contemporary Appalachia.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Write Around the Corner is a local public television program presented by Blue Ridge/Appalachia VA

Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner - Robert Gipe

Season 5 Episode 10 | 28m 8sVideo has Closed Captions

This episode finds in Harlan, Kentucky, to talk with Robert Gipe about his innovative trilogy – Trampoline, Weedeater, and Pop. These illustrated novels introduce us to a cast of characters and a range of issues in contemporary Appalachia.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Write Around the Corner

Write Around the Corner is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[♪♪♪] -♪ Every day every day Ev ery day every day every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ [♪♪♪] -Welcome.

I'm Rose Martin, and we are Write Around The Corner in Harlan, Kentucky, with novelist Robert Gipe.

His innovative trilogy, Trampoline , Weedeater , and Pop , introduced us to a cast of characters and a range of issues in contemporary Appalachia, from domestic violence and substance abuse to strip mining, all the while, he has us constantly thinking about social and environmental justice.

Welcome to Write Around The Corner .

-Thanks, Rose.

It's great to be here.

-And it's beautiful.

What a great day that we have to be outside, here in Harlan.

-Sure is.

-So, you've got this innovative trilogy that we'll talk about in just a few minutes.

But I want to know a little bit about your background, where you came from and your, um, your theater background.

So, let's start there.

-Okay.

-Who is Robert Gipe?

-Well, uh, I was actually born in North Carolina, but when we were three, my parents moved back to Kingsport, Tennessee, where they both graduated high school.

And, uh, actually, my dad, he went to at least three high schools, two of which were in Virginia, in Winchester and Harrisonburg.

And then he-he-he was a senior, moved to Kingsport, where my mom grew up.

And so, that's where my brother and I grew up.

And then, I went to Wake Forest University.

I got involved in kind of college radio and-and listening to a lot of the music that's in the books, kind of punk rock-centric, uh, roots music kind of thing.

And then, I went to grad school in Massachusetts at the University of Massachusetts.

And I came back from there and worked at Appalshop, which is a media arts center that's in Kentucky and Virginia, um, and worked there for six years.

They made documentary films, among other things, and I worked with the schools to use those films.

It was a-- it was a brave new era.

It was right when VHS came out.

-Mm-hm.

-And so, that was pretty exciting for these 16-millimeter filmmakers that their school-- their work was accessible to the schools.

And so, I had a lot of experience in the K-12 environment, just like working with artists and teachers.

And, um, then from there, I ended up, I had a little sojourn in philanthropy, helping rural schools get grants from this rural foundation that was looking to help schools connect their curriculum to their local culture.

And then landed at Southeast Kentucky Community and Technical College in 1997.

And I still work there part-time.

Um, but uh, taught Appalachian Studies, had kind of a broad mandate from the president of the college at that time to connect local culture to the college so that first-generation college students, which many of our students are first-generation.

less so now, but at that time, much more so, were first-generation.

And, um, and so, you know, it's just doing cultural work.

My students and I wrote a proposal along with some of my colleagues to the Rockefeller Foundation to use the arts to address the opioid crisis, and that was in 2002.

And out of that grew several projects, but the kind of most enduring one was a project where we did interviews in the community and then worked with local musicians and theater professionals, both locally and from outside the community, to create kind of large participatory theater projects with non-professional actors.

And in the process of, um, doing that, I kind of got involved in the playwriting.

From there, after seeing some of our work on stage, um, decided to start going to the Appalachian Writers' Workshop at Hindman, Kentucky, at Hindman Settlement School, to kind of start working on my own writing.

And, uh, and nine years later, the first time was in 2006, uh, my first novel came out in 2015.

And I was a overnight sensation at the age of 51.

-[Rose laughs] -So, uh, yeah.

So that's how I got to books.

-Well, it's a great pathway.

So, books really weren't something you were always writing from a little boy.

You weren't sitting down in the room and writing stories or crafting stories.

It sounds like you were more into the theater and the performances part?

-Yeah, really, I was more into the drawing.

I hated theater, to tell you the truth, I was forced to be in an operetta when I was in sixth grade.

I played the-the woodsman that was supposed to kill Snow White, and I had to sing a solo called "I'm a Terrible Terrible Terrible Man."

And I was-I was-- -Oh.

-Yeah.

You know, I was laughed at by my community and I hate theater.

-[Rose] Mm-hm.

-I did then.

I see its power now, but actually, I was-- I was more interested in the drawing and cartooning.

I think if you probably went back to Kingsport, people who knew me, they thought that what I did would be more in line with that.

Um, but, uh, but I was an English major, so I read a lot of books.

Um, uh, but yeah, I think until I got involved in that community work, I kind of thought that just writing your own books was, I don't know.

I didn't quite.

It seemed like it took a lot of time being by yourself and, um, you know, just kind of doing things for yourself.

And the impact that the theater work we did had on helping our community process, you know, what was going on with OxyContin and the opioid crisis at that time.

Um, because, you know, and when we did that first play, there was, there was an even weaker recovery culture, rehab culture, than there is now.

We've come a long way in terms of that.

But at that time, in 2003, 2004, 2005, when we were starting this work, um, you know, that-that work, both the interviewing in the communities, and then the productions of the plays, I-I really did feel like it had an impact on just helping people to think through what was happening because it was, you know, the arrival of OxyContin, and the way that it affected the nature of substance abuse in our community really was a shift, and people were having a hard time figuring out what to think and feel about it.

-Well, we see that in the books, how things begin to grow.

Um, I read someone who had an impact, serious impact on your life was your dad, by not forcing you down a certain path, but you also felt that he guided you in a way that made you who you are today.

But I thought something else because I read about something with your dad and Aunt Bernice.

So, you kind of give her credit, too.

Who was Aunt Bernice?

-Well, so my father's mother passed away when he was four years old.

And, uh, he got sent to his-- and his dad was working, and so he got sent to live in Fort Wayne, Indiana with his dad's sister, uh, Aunt Bernice and her husband, uh, I think we called him Uncle Spike, but, uh, so yeah.

So, he grew up out there.

And, um, uh, I guess she was-- we always were kind of scared of her a little bit because she's, because Dad had told us all these stories about her.

And I mean, the most memorable one to me and my brother was that, uh, Christmas Eve, she told him not to come downstairs, or Santa Claus wouldn't come.

And he came down anyway and looked at his presents and played with them, and went back to bed.

And when he got up the next morning, they were all gone.

And, uh-- -I've read that, so that's true.

-[laughs] It's true.

And, uh, didn't give them back, either.

Um, and so, you know, we thought she was kind of a tough customer.

But-- -Yeah.

-And then, then we met one of my dad's first cousins, like decades later, and he said, you know, it's like, Aunt Bernice was really not-- because his-his dad was my grandfather's other sibling.

And he had sent him out to live with Aunt Bernice, too, that, which is a story I'd like to hear more about, how they all ended up at her house.

But anyway, he said that when Dad had come to Aunt Bernice's farm that-that he was pretty-- he'd been awhile without a mom, and his dad was working.

And so, he was pretty undisciplined and wild, and that she kind of had to take him in hand.

And he always gave her credit for really, uh, making him into the-- he was a fine person, a very disciplined person.

But, uh, he always gave her credit, but we never kind of heard that part.

We always heard the risk of her being anti-Santa Claus, and so.

-And the risk that you might have to go there for a while.

-I met-I met her again later.

And, um, she was a lovely person.

She's a schoolteacher, and really, none of that was-- just, you know, you know how things go.

-Well, in the mind of a child too, and what you hear.

-Oh, that was a house of horrors, as far as me and my little brother were concerned, yeah, but, uh-uh, that was just a misperception of youth.

-So, your love of words and your love of language.

You did your Master's thesis on Emily Dickenson.

-Yeah, that's correct.

-.but yet, you had MAD magazine of the '70s as kind of something that you drew from also, for inspiration.

How do you marry those two things together?

Your love of language and words then to the-- to the things from MAD Magazine, and then eventually, we're gonna get right here how you blended both.

-Okay.

In my mind, it's a-- it's kind of a harmony between those two types of text.

I mean, Dickenson, you know, was-- one of the reasons I was drawn to her was just her persona, you know.

That-that she kind of cast herself as an isolate, someone who was outside of the literary world, and yet she kept a pretty healthy correspondence up.

And, and obviously, she was, um, reading enough poetry to innovate off of what existed.

And I think that, you know, one of the things that always appealed to me about MAD Magazine, you know, is like, whatever the story was, wherever they were parodying, there was that main story that they were, you know, adapting to their own purposes.

But then in the drawings, there'd be, uh, you know, there'd be other things going on that added to the text, and it really forced you to think about what was going on in the margins.

And I really think that was kind of part of Emily Dickenson's era-- errand, too.

It's, like, you think that, you know, nothing's happening with a person or in a-in a visual frame, but really, there's a lot going on that most people don't pay attention to.

And I was kind of interested in that stuff off to the side as much as, you know, the main story.

-Well, and that's what I loved about your books because the illustrations really were something that, you know, were so poignant, and that's so meaningful.

At first, you think, oh, when you just look at the covers, you're gonna think, "Oh, there's going to be some fun kind of messages or something about them."

So, was that a conscious effort to, when you drew the drawings-- I understand you had double the amount of drawings that they actually used in the book-- to actually, a character voice to speak?

Or were you trying to send the message of what the storyline was that you were carrying through at the time?

-To a large extent, just the.

I mean, if I could have drawn better, I would have done a graphic novel, but I don't really have the talent for that.

So, you, I mean, I would say this to, um, uh, anybody who's trying to do anything really, it's, like, it's not about what you can't do.

It's like how you make the most out of what you can do.

-Mm-hm.

-And, uh, and so, you know, I was just trying to maximize what I had.

And I love, uh, the drawings, and just visual art, generally.

And, um, I think the thing also that was going on with them is that I'm real fascinated with oral versus written language.

And I was really interested in-- and because so much of my background in terms of having a story was grounded in interviewing and listening and just talking with people, that I was very interested in the first-person narration.

And, um, and so, having the kind of head-on, uh, breaking the fourth wall, character speaking to you directly, sometimes stepping out of the narrative to, you know, address you directly, the drawings were meant to kind of underline that phenomenon th at was happening in the text.

And-and again, it also it, there's a lot of cases in the drawings where I was using those lessons learned from MAD Magazine and Emily Dickenson, whether they serve as a kind of marginalia.

-[Rose] Mm-hm.

-.

that kind of add things that, that add things that aren't in the text.

[Rose] Well, even with some of the messages on the shirts, you know, at first, I didn't pick up on that.

And I'm, then when I looked closer, I'm like, "Oh, you've got subliminal messages here," if we look at that, and then, where they were placed in the text was really interesting, too.

So, the process for putting the book together, um, what is your process?

Computer?

Pencil, paper?

Drawings first?

Text first?

Character analysis?

Where does it start?

-The teacher I spent the most time with when I was figuring out how to do this, a Virginian, Darnell Arnoult, taught us to just write scenes, you know.

Just-just think of it as almost like, you know, where would the cameras sit?

And how would, and how would the characters within the scene act, and what would they say to one another.

And just endlessly write scenes around the character, develop your characters first, figure out who they are and what they're about, and then put them in situations.

And so, uh, and I did an extended novel workshop with her and, um, and so you know, wrote hundreds of scenes and then, uh, did kind of a thinking draft where you're trying to figure out what is actually happening in your book.

And, um, uh, and then rearrange things to make them like a narrative sense.

And so, um, at some point, um, I pretty quickly settled on first-person and-and my creative pro-- you know, generative process is I start with note books, and I write it all out in longhand.

And the drawings kind of come naturally like when I can't think of what to say next, I'll draw and then-- and then type 'em up and look at 'em, and just push it around till it makes sense.

And so then, once I get the text, then I go back and make final drawings.

And in the first two books, we were just kind of, you know, the publisher just fit 'em in.

They just took whatever I gave 'em and fit 'em in however.

But by the third book, I worked a lot more with the publisher on how to-- that's the one where I drew a lot more than we actually used because it became about how do we make the spreads make sense.

And you know, where did the page breaks fit so we weren't cramming the pictures in.

It was more, you know, fitted.

-Well, and I love that.

So, the three books Trampoline , Weedeater , and Pop , I read that you do one-word titles, and you work backwards.

True?

-Well, in that workshop, the workshop with Darnell, uh, part of her process.

she-- a lot of her-- the people that come to her are people who are later in life or people who don't know if they're supposed to be writing a book or not.

So, she does a lot of visualization stuff to help you think about yourself as a writer.

-[Rose] Mm-hm.

-And so, I had the first, I had Trampoline , and, um, I wanted the books to have one-word titles.

I wanted it to be something that all my students at the community college would recognize as something from this area.

And you know, and the one-word titles are kind of more punk rock, so that was all part of that.

-Oh, and you listen to music while you write.

True?

-Sometimes.

-Okay.

-Yeah, and, um, but anyway, so she said, name all the novels you're ever gonna write just as-- just so you can see yourself with that shelf full of books.

And, um, and so, that's when I did it.

And so, for the second two, I started with the title and then figured out what the story would be.

-Well, introduce us to the characters.

Who, what's your, who are the cast of characters?

Well, let's start with Trampoline .

-Okay.

So, they're all set in the same geographical area, where Tennessee and Kentucky and Virginia kind of fit in, fit together, um, and so, but the primary setting is a coalfield county with-- it's Canard County, which is imaginary, you know, it's a made-up county, but-- and the main family is the Jewell Family.

The narrator that's in all three of the books is named Dawn Jewell, and she's, she's 15 in the first book, and 28 or 29, the second book.

And then she's 38 in the third book, and she has a 15-year-old.

And so, in the first book, Dawn's mom is kind of falling into addiction, and her grandmother's an environmental activist.

And so, she's kind of trying to, you know, save the planet, save the world, save the community, and her mother's just, you know, has almost-- eventually gives up on saving herself.

And so, Dawn's caught between the two, trying to figure out how to, how to, um, just grow up, you know.

She's not really getting quite what she needs from her parents.

Her father has been killed in the coal mines.

And so, then she has a relationship with her father's family, who through the first two books, are kind of outlaws.

And then, in the third book, Hubert, her father's brother, becomes a narrator.

So, the first book has one narrator, the second has two, and the third has three narrators.

And so, then the other narrator, narrators are.

In the second book Weedeater , there's this guy that mows, mows the yard for some of Dawn's relatives, who falls in love with her aunt, and he's a narrator.

He and Dawn narrate the second book.

And that one's more about, um, this kind of art in the coalfields and how art does and doesn't help us to address issues-- I was kind of more reflecting on some of the work we've been doing here.

But there's, you know, it has.

all the books have a lot of car chases, and-and stuff like that in them.

Um, and then in the third book, uh, Dawn is very, very depressed.

She's had a lot of loss in her life.

And so, she's trying to, um, she's kind of on the brink of falling into some kind of self-abuse herself.

And so, it's-it's narrated by her and then her daughter who's both trying to find her way and help her mom survive.

An d so, it's kind of driven by, is the pattern going to repeat itself, and what, what keeps this pattern of self-destruction from repeating itself.

And then Hubert's, the third narrator in it, and he's trying to, uh, go straight, and, um, he's finding out how difficult it is.

And then in the third book, they're also shooting a movie in the community, and it's set in the time of the Trump-Hillary Clinton election, and how that was affecting the community.

So.

that's an overview.

-So, I know how important it is to you about the perception of Appalachian stereotypes.

And you didn't really want to highlight that or make that a focus of the books, but yet it is contemporary Appalachia.

So, I think it's important that people understand like, what do we get right, and what do we get wrong.

-Well, I think, um, you know, it's like, I grew up about an hour and a half from where I am now in East Tennessee, with very low unemployment rates, still a lot of factory jobs.

And, and, you know, and here in Harlan, just an hour and a half away, you know, the-the local economy has been pinned to the coal industry, which has been very boom-and-bust.

And coal industry has had a very complicated relationship with other kinds of economic activity coexisting with it.

So, there hasn't been a lot of preparation economically for when the coal industry failed.

And so, you know, there's just been a hundred years of intermittent hard time for the, really, the majority of people here, even when things are good.

Um, and so, I think it was two things that just I wanted to try and get across using fiction.

One was, for people here, you know, it's like, before I started writing, I'd been teaching in the community college for ten years, and had seen all these students who were just as talented and intelligent as I was, who really didn't think much of themselves intellectually.

They didn't think much of their capacity.

And, you know, I couldn't help but see them as just incredible survivors, and incredibly resourceful, and really making, within the kind of constant calamity of their lives, really pretty good choices.

And so, I wanted to try and show them that I was seeing 'em and seeing that, you know, they were really pretty heroic, just as they are.

And, uh, and then, from the point of view of readers who might be outside the region, for whom this was just one of hopefully many ways that they took something in, to try and think about this part of the country, is that-- that, can you present the complicated reality of people and the hard choices, and the frustrations that result, really not from a person's doing, but just because of the way things ended up in terms of the capitalist economy, and the way it played out in this part of the country.

And, and really just put readers in the same barrel that people here are in so that they-they don't know whether to be sympathetic or to be mad at or, you know, really just to frustrate the readers while you are trying to give them a character that they can relate to, so that they can see how frustrating life can get here.

And that if you can give maybe a reader that's had a more comfortable background, that kind of frustration, maybe they can get it that it's not necessarily about the people.

It's about the situation that-- that we allow to exist in a whole area, like it does here.

-That's a good message for everybody.

Would you be willing to read something for us?

-Sure.

-Okay.

What did you choose?

-Uh, I chose a little piece out of Pop .

Okay.

Oh, it's, uh, so this is, this is the book where Dawn is kind of on the brink and she's kind of shut herself down and is mostly living on the internet.

And, um, her aunt, who's a community college teacher, is in cahoots with these people who are making a movie in Canard County.

So, this is Dawn talking.

"I woke up at five.

"Sam and Willett and Louisa were gone.

"I hoped they were sober enough to drive.

"The snow was coming down hard.

"I tried to call them.

No answer.

"I lay back down and fell asleep.

"When I woke back up, the snow was two feet deep.

"I still couldn't get ahold of them.

"I couldn't get ahold of Hubert.

"I called June.

I got her, but before I could ask "about things of concern to me, she had to tell me "some horsehit story about "how the movie star Tanner Cheathum "was in Canard County.

"She said, 'And he wasn't even here "as part of Quin's movie.'

"I said, 'Who the fuck is Quin?'

"And she said, 'Quin Pennyroyal, "the director of The Hunted .

"The one I been talking to.'

"I said, 'I heard they weren't using Hubert's cabins.'

"June said, 'Yeah, but the project overall "is gonna be huge for the county.'

"I said, 'Is that right?'

"She said, 'You don't think so?'

"I said, 'It'll be awesome for the same five "always makes money off things.

"It'll be awesome for motels and restaurants "and whatever off from here.'

"June said, 'They had to spend some money local.

"That's how they get their tax breaks from the state.'

"I said, 'What's 'local' mean?

"Long as it's in Kentucky.'

"She said, 'They're renting three houses on my street.'

"I said, 'What's the story of the movie?

"What's it about?'

"She said, 'It's science fiction.

"Aliens are bringing in drugs "that turn the mountain people into monsters.

"It's textured.

Layered.

Very metaphorical.'

"I said, 'People from off coming in "and turning us into druggies.

"Sounds like reality.

But dumber.'

"June said, 'Dawn.'

I said, 'Why their stories?

"Why can't they tell our stories?

"Why can't we tell our own stories?'

"June said, 'Maybe this is how we get to that.'

"I said, 'What happened to the 'Nothing about us without us' "you used to teach us?'

"She said, 'I know, but--' "I said, 'What about all the people "don't have nothing to offer the movie people?

"They need work.

And care.

And civilized treatment.

"Not some trickle-down horseshit like this.'

"June said, 'Dawn.'

"I said, 'Well, at least Willett got Nicolette "back to Tennessee.'

Phone went quiet.

"I said, 'Didn't he?'

"June said, 'I don't want Nicolette "to leave Kentucky too quick.

I left too quick.'

"I said, 'Why are we talking about "what you want for my daughter, June?'

"June said, 'I know, but--' "I said, 'June, are you trying to tell me "Willett didn't take Nicolette back to Tennessee?'

"June said, 'Dawn.'

I said, 'Where is she?'

"June said, 'Dawn, she's upstairs.'

"I said, 'Don't you 'Dawn' me.

"You know it's best for her to go back to Tennessee.'

"June said, 'I'm not sure it is.

"She's got friends here.'

And I said, 'Who?'

"She said, 'Pinky.'

And I said, 'Who else?'

"She said, 'Marla Butcher.'

"I said, 'Marla Butcher?

Lord have mercy.

"That druggie heifer and her outlaw clan "make the Jewells look like a bunch of church women.'

"June said, 'Maybe at the end of the school year.'

"I said, 'Is she with you?'

June said she was.

"I said, 'I'm going back to Tennessee.

"It'd be nice if my only child went with me.'

"June said, 'When you going?'

"I said, 'Soon as I can get off this mountain.'

"June said, 'Why don't you stay here with me?'

"I looked around Cora's house.

Seen visions of my momma "tramping through that very living room, "looking for stuff to steal off Mamaw.

Off me.

"I looked out the window, "at the snow burying the bushes in the yard.

"I smothered.

"I said, 'Y'all got power?'

"June said, 'Yeah.

Do you?'

I said, 'Yeah.'

"Said, 'We can figure this out tomorrow.'

"June said, 'We love you, Dawn.'

"I said, 'I love y'all too.'

"I hung up.

A lonesomer feeling I ain't never felt."

-Mm.

The language, the con-- the context, the dialogue.

It's all part of the stories.

It's all makes it, those voices, that you can actually hear the interactions of everybody.

So thankful for you to join us today.

I really appreciate it.

My special thanks to Robert Gipe for inviting us here to Harlan, Kentucky, and to go over all of his illustrated trilogy, Trampoline , Weedeater , and Pop .

The voices of the characters will bring you right into contemporary Appalachia, and I think that was his goal.

Stick around because we're having more of this conversation online as Robert's going to share more about the characters and other projects he has going on right here in his community.

I'd be grateful if you would share this link with others.

So, until then, I'm Rose Martin, and I will see you next time Write Around The Corner .

[♪♪♪] -♪ Every day every day Ev ery day every day every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ [♪♪♪] ♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪ ♪ Every day every day Every day ♪ ♪ Every day I write the book ♪

A Continued Conversation with Robert Gipe

Clip: S5 Ep10 | 25m 5s | We'll dive deeper into the characters and background of Robert Gipe's illustrated trilogy. (25m 5s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Write Around the Corner is a local public television program presented by Blue Ridge/Appalachia VA