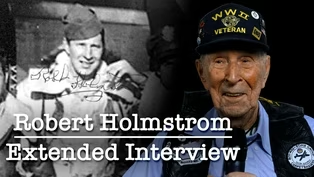

WWII Carpetbagger Robert Holmstrom: Extended Interview

Clip | 36m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

Hear from WWI Veteran Robert Holmstrom as he recounts his time as an OSS Carpetbagger.

Robert Holmstrom is a WWII veteran who served in the Office of Strategic Services, participating in the secret Carpetbagger Operations. Hear his personal retelling of his experience in this extended interview.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Production sponsorship is provided by contributions from the voters of Minnesota through a legislative appropriation from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund, Explore Alexandria Tourism, Shalom Hill Farm, West Central...

WWII Carpetbagger Robert Holmstrom: Extended Interview

Clip | 36m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

Robert Holmstrom is a WWII veteran who served in the Office of Strategic Services, participating in the secret Carpetbagger Operations. Hear his personal retelling of his experience in this extended interview.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch

is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(bright music) - When we left England in July of 1945, each crew of 10 was taken into a private room with a lieutenant colonel and raise your right hand.

And he had a Bible on the table and they said, "You'll not talk about, speak to anybody about anything.

Give 'em a hint of what you did for 40 years."

That was to protect the people that were underground people in Europe, that their relatives wouldn't be shot, killed because they were related to the person that helped defeat Germany.

The repercussions were, would you like to spend the rest of your life in Leavenworth (audience laughing) or be shot?

(triumphant music) Things around the whole world were just in depression and every country was the same.

Even with Hitler, as bad as he was, he doing the same thing President Roosevelt was doing.

He was starting to get things going, manufacturing, putting people back to work.

Hitler was doing the same thing but in the wrong way.

So it was so sad to see people standing in food lines waiting for a bowl of soup.

Some people are doing that yet today.

I ended up in the service.

I used to go to home and field when it, they were flying Ford Trimotor airplanes and I was hanging around there and we were really, really poor.

But I had saved money from selling newspapers and I had $10 in my pocket and I got a ride in a Ford Trimotor around Saint Paul, Minneapolis, and they took about a 30 minute ride and it made me so enthusiastic.

I thought, "When I get older, I'm gonna fly."

(chuckles) Was 17 years old in high school at Harding High School in Saint Paul and a couple of us were talking.

And so one day I just got on the street car, went over to the Minneapolis National Guard Building and told 'em I wanted to sign up.

I wanted to be in the Army Air Corps.

And they said, "You're too young.

You can go in the Marines or be in the Navy."

And I said, "No, I wanna fly."

So, I took the test and passed the test at that time and they'd said they would call me when I was 18 years old.

And they did.

So, it worked out really well for me.

In the April of 1944, President Roosevelt abolished all flight training.

They had enough pilots they figured to finish the war and win it.

We were then recruited into the OSS.

The OSS is the Office of Strategic Service.

And there was only two bosses of the OSS, President Roosevelt and General Donovan.

That was all.

There were no one else to answer to.

It was quite an occasion.

We were sworn to secrecy for everything that we did.

We were told not to talk to anybody about what we did, what went on, or any incident that we knew of.

Went to school.

It's like 12 hours a day learning languages learning how to eat European style, how to smoke European style, how your actions of what you do is so critical that if you make an error, you're dead.

For instance, we're all right-handed or most of us are right-handed.

You take a fork and put it in your left hand and a knife in your right hand.

And then when you get done cutting your meat in small pieces, you switch hands, you put your knife in your other hand and your fork in your right hand.

If you did that in Europe, you're a dead man.

Operation Carpetbagger was supplying the underground in Europe with weapons and material that they could use to harass the Germans.

For instance, when we dropped some supplies in the container that held 300 pounds with a bumper on the bottom and a parachute on the top, just so it wouldn't break things up.

There might be dynamite to blow up railroad tracks, blow up a telephone pole just to harass them.

And it might be a bazooka, it might be a pistol.

We had throw away pistols that held seven shots just made outta sheet rock and you, sheet metal and you throw it away when you get done.

And then we had 38 caliber pens, believe it or not.

Now when we dropped those to the patriots, they could walk up to a German soldier and ask a question and pull out that pen and as soon as they hit his body, the shell went off.

They killed him, and walk away.

Throw the pen away.

It was kind of a goofy thing, but it worked.

During the Civil War, the Carpetbaggers were in covered wagons.

They went from north to south and south to north.

They crossed the border.

They were kind of natural spies because somebody would question them as they crossed the border and they would wanna know where the big army outfit was that was shooting at him.

And this Carpetbagger person, he could say, "Well, I was over there, I was within a couple miles of their place and I seen all kinds of soldiers.

I seen a lot of horses and cannons and all kinds of stuff."

So the other party would know approximately how many people to fight, how many people to spend each way.

And it worked both for the south, it's worked both for the north that they took up the name, Carpetbaggers.

So we were fighting and dropping supplies.

And so the Carpetbaggers, they were pedaling booze and they were peddling food and liquor and pots and pans and kettles and anything to help people survive during the Civil War.

And we were helping people dropping supplies, so we took up the name, Carpetbagger.

The B24 was a four engine bomber, Pratt & Whitney engines.

And it could go top speed was 303 miles an hour.

We never went that fast.

And most of our cruising speeds was on a hundred eighty, a hundred eighty five miles an hour.

The aircraft was built, so I could walk really from tail turret all the way up to the pilot's place up to the front of the ship where the nose gunner was sitting, standing up.

A 17, you could not do that.

My possession in the 17 would've been laying on my belly isolated.

And I would have to enter a door from the outside and I could never get back into the airplane if something happened to it because the tail business was was in between the waist gunner and the tail gunner.

He was really trapped back there.

And another thing about the air, the difference of the airplane was the 24 could handle almost once and a half times the weight carrying.

We could fly further, we could fly higher.

So it was a workhorse of the war.

That bomber that we made, I think is 28,000 of them.

It was a highest built bomber of any ship during the war.

And they would in Detroit, Michigan, they could build one in every hour, believe it or not.

You wonder how they could get all those pieces together and taxi it out.

It's amazing.

There was a program and when we got over to England, we would go on training flights west of western shore of England and give us, the pilot would give us training of flying the 24.

Each one of us could fly that airplane.

We got 10 hours of training because whatever was on there was so expensive, secret.

And if we didn't want the Germans to get ahold of anything else, it was wired to blow up if possible after everybody bailed out.

And it was really, really something different, I tell you.

Everything we did was different.

(chuckles) We were promoted as we were learning and learning how to handle ourselves and how good we did in school, learning our things that we're supposed to do.

And when we got overseas, then we were made staff sergeant, because now the sergeant in Europe is right next to an officer, believe it or not, and so you get treated better if you get captured.

Now, if we were to be captured, we were always told to approach an airfield, the Luftwaffe 'cause they had their own prison camps.

And being a flyer, you would be treated better in their camp than you would being captured by a German army person, 'cause there was two different lives altogether.

It was just one of those amazing things.

They respected the fact that they were flying and we were flying and they treated us like that.

I was the tail gunner and I had the two 50 caliber machine guns next to me, just like I'm sitting right now on my right and my left.

And we would test fire those as we went across the channel to make sure that they worked.

My responsibility was to inform the pilot when the airplane would come and attack us and give them the position that the plane was coming in at, so he could do evasive action.

And then when we were ready to drop some material, sometimes I would have to get out of my turret and open the trap door in the back.

For instance, if we dropped pigeons.

Now it sounds funny, but we dropped pigeons in the like a Quaker oatmeal box and have the small parachute on it with a barometric fuse that exploded the parachute on the box and dropped a pigeon safe on the ground to the patriots so they could send messages back to England to our base.

Believe it or not, those carrier pigeons made it back sometimes the day after we dropped them in Europe and kept everybody informed what they were doing.

We only did that where radio communication was very poor, which in the mountain area that was common.

When we left the airport in England, all the radios were off.

You couldn't talk to anybody, you couldn't communicate.

Like if we were in danger and we're gonna crash, we couldn't inform anybody.

We couldn't send out an SOS.

No way, we were completely isolated.

When we took off, nobody knew where we went except I said the navigator and the pilot, and of course our control tower in England knew where we were.

That's all.

When we went out, like I said, it was kind of a Kind of a bad situation, but it couldn't be changed brcause if we broadcast then the Germans could find out where we were, you know?

They could triangulize the sending operation of our radio and know exactly where we were.

Other than that, they never knew where we were.

Sometimes we hardly knew where we were.

(chuckles) I didn't know personally what we were dropping or to whom it would be.

We were the only people that knew where we were going was the pilot and the navigator.

And the only way we found out where we were going was, as we were flying, my navigator, about every six to eight minutes would say, "Over to your left, six kilometers is an orphanage."

It might be a safe place to go if you crash land or have to bail out, get shot down to seek help.

And it might be a someplace else.

He would answer again that there was a church or some political place where it would be possible to seek help.

And so that's why we had to learn several languages.

We didn't know which country we were going to be going over that particular time.

Everything was on the need to know basis.

And we would go out and get it in the airplane, say at 10 o'clock at night, and turn the props and get the oil out of the bottom cylinders of the engines and climb in the airplane.

And we would have about maybe 30, 40 airplanes taking off.

And the supplies were already in that airplane.

But the people that loaded it never knew what was in it either.

The containers were like 300 pounds a piece.

They were big.

I could just barely reach around one of the containers.

And they were about seven and a half feet long.

And they would hold many, many different things.

Everything from blood plasma to radios to bazookas to rifles and hand grenades and medicines of different kinds, shoes and socks, whatever the patriots could use because they lived in the mountains, they didn't live in town.

So when we dropped our material, they scooted out and picked up the containers and went back up in the mountains again or the hills, wherever they could live because there was a lot of open space in Europe.

That was, nobody lived at all.

Some of it really bad country.

(chuckles) You had to be real survivor to be one of those people.

My airplane was not equipped with the equipment they needed to drop a person.

If a person, if it's generally a group of three, they would drop an American officer that could speak the language for that area.

Somebody that lived in that area or was born there or lived in Europe previous to the war, or their family did, and a radio operator.

The three of 'em would bail out together.

And when they got loaded in an airplane, the pilot of that airplane did not know they were coming out.

They come out in the truck.

And then they talked to the pilot and let 'em in the airplane.

Otherwise they had no way of knowing who was getting on what airplane.

It's crazy, but that's the way it was.

So secret.

Some missions were like only six, seven hours, some where 10, 11.

We had enough gas to last that long.

I've flown over as far so I could see Switzerland with all the lights on during the war.

It looked like New York City.

I've flown as far as Russia.

I had Russian ID, everything to be recognized there in case we had to stop over and get some gasoline or maybe lost an engine and couldn't make it back to England again.

I talked to people that did land in Russia and they said it was really, really bad They were our allies, but they didn't treat us like they're allies.

They said when Americans landed their airplane there, they were isolated by their airplane.

They had to stand guard over it, so the Russians couldn't get it.

They couldn't even get to go to barracks.

They even hesitated to feed them.

Although they were supposed to be fighting the Germans the same as we were.

It didn't make sense.

They didn't cooperate at all.

Sweden was a neutral country.

So when we flew to Norway to help Norway out, sometimes our planes would land in Sweden.

The Germans also landed in Sweden.

Everybody guarded their own airplane.

And I heard one story where the control tower operator was talking to the American pilot, and he said, "I'll fix it, so you won't get shot down on the way out."

And I said, "What?

How could that happen?"

Well, they figure that the American pilot would take off and fly back to England and the German fighter would follow 'em 20 minutes later, catch up with 'em and shoot 'em down over the ocean.

Imagine that.

They had it all planned.

So this guy in the control tower delays the Germans every time they wanted to take off after an American.

And it worked out really well for us.

And we had a secret base in Norway with a secret room with radio operator in it and that still stands today, that room still stands and it's open for inspection by the public.

It's really something.

We didn't lose a lot of men because flying at night, the Germans weren't really afraid of a separate airplane flying all by itself and they couldn't figure out where we were going because we would fly about four or five, six different dog legs on the way to our target.

So there was no direct heading where we're gonna drop the supplies.

And flying so low they couldn't get enough fighter plane underneath us to shoot us down.

But the ground fire, sometimes we get some rifle shots through the airplane.

And the aluminum on a B24 or a 17 was so thin.

Imagine that a paper matchbook, how thick it is.

A BB gun could shoot it right through the side of the airplane.

No protection at all.

We didn't have any flack jackets or helmets or not a thing.

No ear protection at all for the noise because it was noisy as the devil.

I'm a hundred percent deaf in my right ear.

About 45% in my left ear.

There was one particular trip we made and I didn't know where we were going when we left the airport in England, but we ended up flying down the Danube River.

And it's a crooked river and we were flying like maybe 300 feet above the water on the river.

And my pilot banked the airplane 90 degrees following the river.

And I looked out and up and there's a castle.

It's 500 feet above me at night.

It scared me.

I tell you to look at something like that.

And if we made a little error, 500 feet, we could have hit it.

My pilot was the greatest guy and so responsible and he could handle that airplane like almost when we come back and landed.

He was such a good pilot.

You would never know the wheels hit the ground.

But it was amazing, you know, the little things that helped what we could have to do to survive.

And we learned to live off the land, eating roots and everything else.

In my 45 caliber pistol, I even had shotgun shells, little pellets.

If I went could out someplace and I was hungry and I could shoot a rabbit and fix it.

It's amazing as the devil.

I had a whole paper box of those and somebody borrowed it when I had a demonstration, so I lost it.

Even two months ago, I was in Anoka at American Legion Club at one of their district meetings and I had it about 40 different things laying out on the table.

Like all our buttons and the material were metal and they were in two pieces.

And if you take one and cut it off and tip it over, it's a compass.

We had compasses so small you could stick in your belly button because for survival we had maps of Europe that were topographical, printed on silk on two sides that the British made for us in 1944.

And I've never seen anything printed like that.

I've been offered up to $300 for the maps.

It's really something.

If one of our planes was shot down, we had airplanes that could fly into Europe and land almost on a baseball field.

We had planes like even a little piper cub that take off after about 200 feet of taxiing and fly 45 degrees, so we could get in there and get 'em out.

But there was a system in Europe, a real trail of people that had a way to get you to Spain, get you to Denmark.

Denmark was a good exit way to get out of Europe and back to England again, 'cause we had boats.

They had boats over there that would take out to a submarine and put the people back into London again and back to our base.

Sometimes it took two, three, four months to do this because of the danger to the people that were doing it and the danger to the person that was trying to get back to Europe also.

We were worth so much money.

The training that we had was you wouldn't believe.

No way.

I'd like to say something else too that on my DD214, which is our paper to get outta the service, there's nothing that says anything that I did.

My records are three stories underground in Falls Church, Virginia.

So everything is still secret.

There's stuff that I can't talk about yet.

I can talk about one thing that I haven't discussed with anybody as yet.

If we got shot down in the Netherlands, they had these windmills with the blades, big blades turning.

Each blade was a different color.

Now if the blade was down on one color, we had a system where we were informed if you crashed, that was safe to go to that windmill and maybe you could get help.

If a ladder was standing outside of the windmill that meant go to the second story after dark and stay there till you get help.

(chuckles) And that's something.

We knew it right away that the war was over.

It really made us kind of happy, you know?

And then things completely changed and we then switched over and dropped supplies for the prisoner of war camps, medicine and stuff and food and medical supplies and what have you.

We couldn't land at any airport in Germany to do this, so we would have to land on the Autobahn.

That was the only place there wasn't a bomb crater hold, so we could land the airplane and unload our material and help.

Water was a big thing also.

That everything was so bombed out over there.

You wouldn't believe that the craters and the fires and the things, oh.

When we would fly at night, you could see a fire 50 miles away.

Believe it or not.

The British had been in there previously during the day and dropped bombs that got things burning.

Burning real bad.

- [Interviewer] I know there's a book about you as well, "Warbirds in the Cloak of Darkness."

Did you wanna take this opportunity to talk about that a little bit?

- Well, that happened by accident.

A friend of mine was talking at a legion club and they wanted to know if there was World War II combat person that they could interview and one knew somebody else and somebody else knew somebody else.

And this retired literature teacher from the Iron Range up in Minneapolis, Minnesota wasn't doing nothing, and so they got ahold of her and they sent her down to my house and I talked to her for about 18 months before we got it all together and it was really quite a stirring experience.

And now she lives down in Florida and her health is bad and I just talked to her last week and it was nice.

- [Interviewer] How did it feel once that time passed and you were kind of finally able to talk about it?

- Well, it was kind of, I didn't hear about it right away.

I don't know why they didn't do this.

But when we did hear about it, then our group of Carpetbaggers, we formed a club and we meet once a year someplace around the country.

We've even met in England, been on cruises together.

Been many, many states in the United States at any Airfield, 'cause we're always welcome.

And all the people with us, the women, the children, they're so interested in what we did.

And they, even the Air Force let's us climb up in the airplanes.

I've sat with the women, I've sat up in the cockpits of Hueys and C130s and fighter planes and what have you.

So, it's been a liberal education in that manner.

It was kinda good, yeah.

Oh, I loved to fly.

It was really good.

I think all of us were so enthused with what we could do, you know, and we were fighting the war to win it and we believed firmly what we were doing was helping somebody.

We never dropped a bomb.

Everything we did was humanitarian.

Even though it was a bombing mission, they called it a mission.

But we never really meant to kill anybody.

It was fascinating and it made me feel good after the war when I was talking to other soldiers and people had been in the military and they were so reluctant to talk about what they did because they killed people and they wanted to forget it.

In my time, I've volunteered for the VA system for 35 years.

And I decided when I got discharged, a lot of people helped me when I was young, and so I decided I would help other people.

So, that was my game.

Yeah.

(triumphant music)

WWII Carpetbagger Robert Holmstrom: Extended Interview

Video has Closed Captions

Clip | 36m 15s | Hear from WWI Veteran Robert Holmstrom as he recounts his time as an OSS Carpetbagger. (36m 15s)

Preview: Special | 32s | The Vietnam Memorial and History Center tells stories of the Vietnam War. (32s)

Dennis Boldt, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 28m 26s | Dennis Boldt is a WWII US Army Veteran who served in different parts of Europe. (28m 26s)

Paul Wojahn, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 10m 5s | Paul Wojahn is a WWII US Marine who fought as a pioneer soldier in the Pacific Theater. (10m 5s)

Delvin Owen, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 7m 31s | Delvin Owen is a WWII U.S. Naval Reserve Veteran who operated test flights on aircraft. (7m 31s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 10m 32s | Bob Brix is a WWII US Marine Veteran who served in many areas of the Pacific. (10m 32s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 11m 41s | David Wooden is a US Marine Corps Veteran who flew a variety of WWII aircraft. (11m 41s)

William Homan, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 6m 14s | William Homan is a WWII US Air Corps Veteran who served as a a mechanic on a b-17 bomber. (6m 14s)

Bill Friberg, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 5m 12s | Bill Friberg is a WWII U.S. Marine Veteran who served as an airplane mechanic. (5m 12s)

Fay Hendricks, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 14m 52s | Fay Hendricks is a WWII U.S. Army Veteran who served in the Philippines. (14m 52s)

Paul Fynboh, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 6m 44s | Paul Fynboh is a US Navy veteran who served as Electrician and loader in WWII. (6m 44s)

Harlan Rosvold, WWII Oral History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Special | 5m 43s | Harlan Rosvold was a WWII US Marine Corps Veteran who served in the Pacific theater. (5m 43s)

Preview: Special | 30s | Meet some of the last few people still building boats in the old Norwegian tradition. (30s)

Clip: Special | 1m 45s | Dragonfest is a two-day summer festival in Madison, Minn. (1m 45s)

Tracy Area Garden and Quilt Tour

Clip: Special | 1m 42s | The third annual Tracy Area Gardens and Quilts Tour (1m 42s)

Clip: Special | 2m 20s | Take a trip to Milan, Minn and watch the U.S. Chuukese Volleyball Tournament. (2m 20s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by: