Greenwich Village in the 1960s was home to a counterculture folk music scene that produced legendary artists like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Janis Joplin and Joni Mitchell. A network of cafes and bars that doubled as music venues—including Gaslight Café, Kettle of Fish, Café Wha? and others—gave way to international stages, mainstream fame and an enduring legacy for a select few.

But there are many other musicians who passed through those New York City clubs whose names you might not be as familiar with. These are just a few of their stories.

***

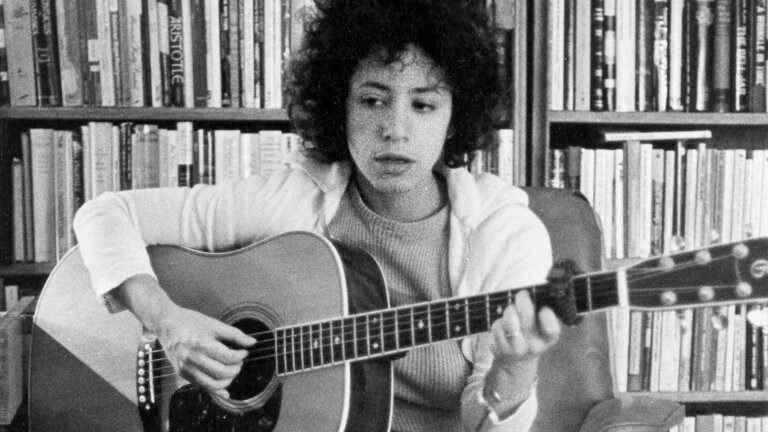

1. Janis Ian

Janis Ian first performed at Village Gate when she was 13. The following year, her family moved to New York and Ian began routinely performing in the Village. Her first recorded single was “Society’s Child,” which was about interracial relationships. It was 1965, and Ian—a young white girl from New Jersey—was suddenly a voice in the civil rights movement.

The steep climb to fame took a toll on her mental health, and at 17, Ian told her manager she was done. She endured the end of her adolescence out of the public eye, survived a suicide attempt and started writing again.

Ian returned to New York with a new single about the unforgiving nature of fame. “Stars” was covered by a host of musicians, including Nina Simone. Soon after, she released the 1975 record “Between the Lines,” which featured “At Seventeen.” The album went platinum. She performed “At Seventeen” on the inaugural episode of “Saturday Night Live” and toured all over the world, including in integrated venues in apartheid South Africa.

For the next decade, Ian retreated from the music industry: she lost her life savings to the IRS because her manager committed tax fraud, endured and ended an abusive relationship, and cared for her sick mother. In 1992, she released “Breaking Silence,” which marked both her return to music and her public coming out. In 2003, Ian and her wife were married in Toronto; they were the first same-sex couple to be featured in the New York Times wedding section.

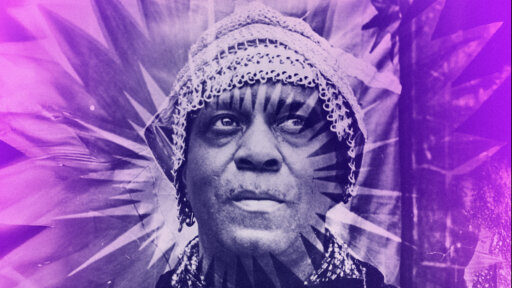

2. Buffy Sainte-Marie

Buffy Sainte-Marie issued her debut album, “It’s My Way!,” in 1964. She had written nearly all the lyrics herself, and the album’s release made her the first modern female singer-songwriter.

It wasn’t her only first: she was the first Indigenous person—and only Indigenous woman—to win an Academy Award. She was the first person to nurse her baby on television and the first artist to make an album over the internet.

From the outset of her career—which took off in Greenwich Village—Sainte-Marie’s work had a political bent. Her first widely-known song was the anti-war protest anthem “Universal Soldier,” which she was banned from singing on the radio or TV until 1965, two years after she wrote it.

Her love song “Until It’s Time for You to Go,” was hailed as a feminist anthem for its insistence on romance as a temporary and ancillary part of life. “To me, the most important line in the song is ‘we’ll make a space in the lives we’ve planned,’ Sainte-Marie said. “That’s about leaving room in your life for life to happen.” The song inspired 157 cover versions, including by Barbara Streisand and Elvis Presley.

Throughout her career, Sainte-Marie was an advocate for Indigenous rights. She guest starred on the popular Western TV show “The Virginian” on the condition that every Indigenous character be played by an Indigenous actor. In many of her songs, she sang explicitly about Indigenous rights and environmental activism—and as a result, the federal government discouraged radio stations from playing her music in the 1960s and 70s. That censorship offers at least a partial explanation for why Sainte-Marie never rose to mainstream fame.

[Editor’s Note – November 3, 2023: Recent investigative reports have sought to raise questions about Buffy Sainte-Marie’s Indigenous heritage. Sainte-Marie has stated that she is uncertain of her biological heritage and affirms her formal adoption into and identification with the Cree nation.]

3. Tim Hardin

Tim Hardin was once the greatest living songwriter, at least by Bob Dylan’s standards. Hardin moved to New York after his discharge from the marines in 1961, ostensibly to attend the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. He was soon dismissed from the school and became absorbed in the Greenwich Village folk scene.

He made his debut in 1966 with a self-titled album. It was not commercially successful, but the songs he released went on to have lives of their own. “How Can We Hang On to a Dream” and “Reason to Believe,” which was covered and popularized by Rod Stewart, remain among his most famous tracks today. Hardin’s second album featured his version of “If I Were a Carpenter,” which (although Hardin wrote it) had already been released as a Top 10 hit for Bobby Darin. The song was covered dozens of times, with versions by Neil Diamond, Elton John and Joan Baez.

Hardin went on to perform at Woodstock and released a number of albums, but by the 1970s he was in the throes of a heroin addiction. At one point, he accepted a briefcase full of money in exchange for his song rights and flew to London, where he could register for free methadone (his wife and son were eventually able to retrieve a piece of the royalties). He died of an overdose in 1980 at the age of 39.

By Hardin’s own account, he did not find social connection easily. “People understand me through my songs. It is my one way to communicate,” he said in 1968. That has proven truer than Hardin could have anticipated: after his death, his son would turn to his father’s music when he needed advice. “He always gives me the right answers, right away.”

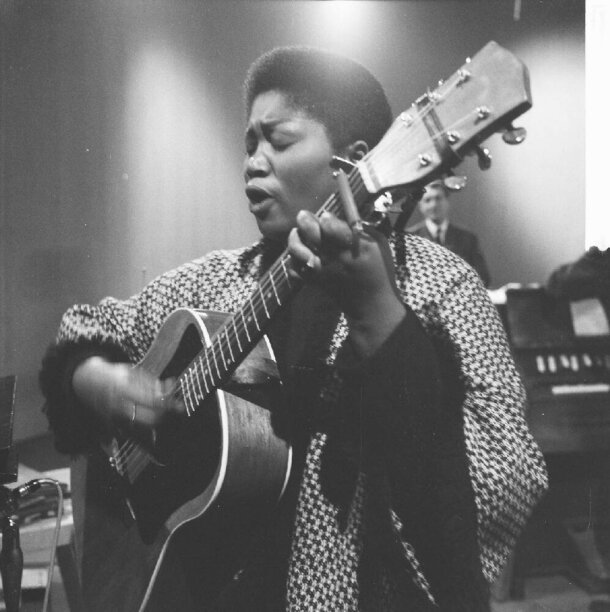

4. Odetta

Odetta, 1961. Photo courtesy of Nationaal Archief, Netherlands.

Odetta Holmes, known mononymously as Odetta, is a (largely uncredited) founder of the folk movement. Her first record was released in 1954, a year after she moved to New York. She spent the decade before the movement reached its peak building out the architecture of the genre. “The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta,” Bob Dylan said in 1978.

Odetta started out as an opera singer until she found folk, which she said felt like home. In the sixties, she played alongside the likes of Dylan and Baez, who both cite her as an inspiration. But her biggest stages were marches: she was best known as the voice of the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King Jr. dubbed Odetta “the Queen of American Folk Music.” She performed at the March on Washington with Joan Baez, where she sang “On Freedom” and “I’m On My Way,” both songs about emancipation. She marched in both Selma and Montgomery, and in 1999, President Bill Clinton awarded her the National Medal of Arts and Humanities.

Odetta described her songs as “a history of us, and [one that] was definitely not in our history books.” She carved out a name for herself as a Black woman who approached both her music and her celebrity as political projects. Undoubtedly, a large part of her inclusion on a list of lesser-known artists can be explained by the racism of the industry and the era. But any honest history of the genre should include her name.

5. Fred Neil

Fred Neil remains largely unknown by his own design. In the 1960s, Neil was a prominent figure in the folk music scene, and he was occasionally backed by Bob Dylan on harmonica at Café Wha?. He’s best known for “Everybody’s Talkin,’” which became a global hit after Harry Nilsson covered it and used it as the theme song for the 1969 movie “Midnight Cowboy.”

Early in his career, Neil was a songwriter for Buddy Holly (“Modern Don Juan”) and Roy Orbison (“Candy Man”). His first solo album “Bleecker & MacDougal” was named after the Greenwich Village cross streets. He was a mentor to some of the biggest names to come out of the Village, including David Crosby and Bob Dylan. In fact, it was Fred Neil who first asked Bob Dylan to play something when he wandered into Café Wha? in 1961. The performance was Dylan’s New York City debut.

In his obituary, Neil was described as “something of a cult figure without a following.” He consistently shied away from fame and had no interest in seizing the opportunity created by the meteoric rise of “Everybody’s Talkin.’” Instead, he moved back to Florida in 1971 to set up a dolphin rescue project with the marine biologist Richard O’Barry, who trained dolphins for the TV show “Flipper.”

6. Melanie

Melanie, born Melanie Anne Safka Safka, was one of just two women who performed as solo acts at Woodstock in 1969 (Joan Baez was the other). She was just 22, and coming from the coffee houses of Greenwich Village, Woodstock’s sprawling audience of 400,000 was an intimidating feat. It started to rain just before Melanie stepped on stage, and the announcer told the crowd to light candles to help keep the rain away. “By the time I finished my set, the whole hillside was a mass of little flickering lights,” Melanie wrote. The scene inspired her to write “Lay Down (Candles in the Rain),” her first hit.

On the heels of that success, Melanie released the album “Gather Me” in 1971. The biggest song of the album—and of her career—came to her when she broke a 27-day long fast with a McDonald’s burger. Coming off a near-hallucinogenic state of hunger, she wrote “Brand New Key.” The playful, bouncy chorus features what was widely perceived as sexual innuendo (I’ve got a brand-new pair of roller skates / You’ve got a brand-new key / I think that we should get together / And try them on to see). The song generated enough controversy to be banned on several radio stations; it also sat at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks.

Melanie went on to build an impressive discography in the years ahead, but those two songs remain her most famous. She’s part of a cohort of artists she would describe not as hippies or flower children, but as “part of the beat generation—people in the Village expressing themselves in so many ways, not being pigeonholed.”

7. Dave Van Ronk

Dave Van Ronk Street stretches from Barrow to Grove along West Washington Place: it’s the block of Greenwich Village the singer once lived on. Van Ronk was so central to the 60s folk scene he was nicknamed “the Mayor of MacDougal Street,” which also served as the title of his memoir.

Early in his career, Van Ronk made a name for himself with new arrangements of older blues songs like “House of the Rising Sun” and “He Was a Friend of Mine.” He traversed genres through the decades, moving from New Orleans-style jazz to acoustic blues to his trademarked modern ragtime guitar.

Van Ronk was an inspiration to Joan Baez and a mentor to Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan, who at times took up residence on his couch. A native New Yorker, he was known for his refusal to leave the Village for any extended period of time.

He was also known for his steadfast commitment to anti-war protests and left-wing politics more broadly. On June 28, 1969, Van Ronk was among the 13 people arrested at Stonewall Inn. He was straight, but he joined the crowd from a bar two doors down when the police showed up. “As far as I was concerned, anybody who’d stand against the cops was all right with me,” Van Ronk said of the Stonewall uprising.

***

Greenwich Village cultivated not just a musical revolution but a political one, and the two fueled each other.

In the film “Breaking Silence,” Janis Ian reflects on her first few performances following the release of “Society’s Child,” her song about interracial dating that ushered her into fame. It was the first song to incite national anger; it would not be the last.

For Ian, who was just 15 at the time, absorbing that anger was more than she’d prepared for. When a group of people in the crowd tried to boo her off the stage, she fled before they could see her cry. But she returned to watch them be escorted out of the venue. “I realized—for the first time—that the song didn’t just have the power to make people angry,” Ian said. “It had the power to make people stand up for what they believed.”