Oregon Art Beat

Author and Screenwriter Jon Raymond

Clip: Season 27 Episode 1 | 9m 36sVideo has Closed Captions

Novelist and screenwriter, Jonathan Raymond, is known for grounded stories of everyday life.

Novelist and screenwriter Jonathan Raymond is known for grounded stories of everyday life, a style he calls “literary regionalism.” His collection Livability inspired Kelly Reichardt’s films Old Joy and Wendy and Lucy. His new novel, God & Sex, is earning wide acclaim, with The New York Times praising its “profound, ancient questions.”

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Art Beat

Author and Screenwriter Jon Raymond

Clip: Season 27 Episode 1 | 9m 36sVideo has Closed Captions

Novelist and screenwriter Jonathan Raymond is known for grounded stories of everyday life, a style he calls “literary regionalism.” His collection Livability inspired Kelly Reichardt’s films Old Joy and Wendy and Lucy. His new novel, God & Sex, is earning wide acclaim, with The New York Times praising its “profound, ancient questions.”

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Oregon Art Beat

Oregon Art Beat is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(feet shuffling) - There's an ancient Greek word that I've always enjoyed, "ekphrasis", which means the joy of describing a visual image in words.

That sense of ekphrastic writing has always really thrilled me 'cause I've always enjoyed describing things.

And like, when you feel like you've described the thing properly, that might be as close to like writerly pleasure as I can get.

The first novel that I worked on was called "The Half-Life," and this is in about 2000.

I was drawn, I think, to a kind of naturalist fiction and where the stakes are kind of a human scale.

I also had the idea that I wanted to write in a regionalist mode.

It's gonna be stuff that takes place in the world that I understand, sort of in my backyard.

It was probably two years of hard writing, and then another year of revisions with an editor.

I remember like really almost a form of like prayer, you know, where it's just like, please let this work because I don't know what I'm gonna do otherwise.

And then amazingly, it sold.

(upbeat music) I mean, I definitely, I lived the dream of the 90s here.

A lot of my 20s were spent being a dilettante and doing a lot of different kinds of things.

Making a movie at cable access and painting weird pictures, and like just doing that kind of experimentation that I think is really healthy for a young, like artistically inclined person.

(upbeat music ending) I was writing art reviews for "The Oregonian," I wrote for "Willamette Week."

I wrote for a "Snipe Hunt Magazine," which was an amazing quarterly punk magazine.

I really think it was radically useful as a phase of my own writing development.

To me, that's something that like every fiction writer should probably have to do at some point just to cure yourself of your own egomania.

So, yeah, Portland gave me like a ton of opportunities to write in that like just basically professional mode.

(gentle music) When I was writing "The Half-Life," my first novel, I wrote the essay entitled "Everywhere is Home, some notes on literary regionalism."

(gentle music) "The specifically regionalist novel allows for an added freedom.

The regionalist novel by its nature speaks in a voice of sideline skepticism and long ingrown memory.

The proverbial old man on the bench.

It understands that even when things happen everywhere, the popping of a real estate bubble say, or the spread of some faddish spiritual belief, they happen everywhere, in particular places and to particular people, in particular ways.

By molding the stuff of history into the form of local plot and character and setting, the regionalist novel allows us to see things we recognize bearing a larger meaning.

It allows us to talk back to history in some way, and maybe even bend it a little if we're lucky."

(feet shuffling) "Livability" was a collection of stories that I began before "The Half-Life."

Stories were something I could kind of finish, you know?

They were things that you could, within a human amount of time, understand if that was working or not.

I was influenced a lot on that story collection by the book "Winesburg, Ohio," an American classic that all take place in the town of Winesburg, Ohio.

It's a batch of character studies and stories that interpenetrate and kind of cross over each other, but describing a small town community.

And I liked that idea as a kind of organizing principle and I liked applying it to a medium sized city, much like Portland.

And then once I kind of understood that it was gonna be that structure, then it was fun to just start kind of roving around town in my way.

Like, oh, that's a story that like is adjacent to that one.

And that one kind of comes in at a different angle.

(vehicle zooming) (rain pattering) "I left on a Friday afternoon.

The minute I pulled away from the house, it started raining and it kept up on and off the whole way out.

Rain doused the windshield, followed by bolts of sun followed by rain again, intermixed with patches of fog, sleet, and buffeting wind.

The weather might have seemed ominous if I hadn't driven the route so many times before, and known there were at least eight micro climates between the city and the ocean.

For a drive to the coast in the wintertime, this was just par for the course.

I crossed the Willamette Valley passing the fallow fruit farms and groves of oak trees, and climbed into the moist coastal mountains.

The thin stands of Douglas fir barely shielding the blasted clear cuts whipped by on either side making me wonder as always, whom the loggers thought they were fooling with their trick, not me."

(birds chirping) (pages shuffling) In 2000, I met the filmmaker Todd Haynes, who moved to Portland.

And I befriended him very luckily and serendipitously at that time.

I moved to New York soon thereafter, and then he came to New York to make the film "Far From Heaven."

- "Tell you what, I'm gonna take you to one of my favorite spots.

On good days, it's got hot food, cold drink" - And he asked me to be his assistant.

- "It's hard to beat that.

- There you go."

- Todd introduced me to his dear friend, Kelly Reichardt.

She had read my first book, "The Half-Life," and liked it.

And she asked me if I had anything else that might be smaller.

And I had a story called "Old Joy" that was really simple.

It was just two old friends walking in the woods and talking.

And one of them going to some hot tubs.

I can't imagine another person in the world who would've seen a feature film in that story, but Kelly did.

She made it here in in Oregon.

She and a very tiny crew of people came out and shot in the actual locations that the story took place in.

We discovered in that process that we really liked each other and liked talking to each other.

And, you know, had kind of some similar sensibilities in a way.

And that led to a project that became known as "Wendy and Lucy."

- "Great dog.

What's her name?

- Lucy."

- Based on another short story that I had written.

- "Who's that?

- It's your sister, she broke down in Oregon.

- What does she want us to do about it?

- No address and no phone either?

- No, not right now.

- You can't get a address without an address, you can't get a job without a job."

- That has then led to now six movies that we've done, and like really like a blessing of my life.

(cheerful music) (pleasant music) (crowd indistinctly chatting) My latest novel is called "God and Sex," and it takes place in southern Oregon in Ashland.

It's about a love triangle between a new age writer, a librarian, and a botanist.

- Please welcome Jon Raymond and Justin Taylor (audience applauding) - "A book is round.

To a Reader, it unscrolls in a single line, left to right, snaking down the page, wrapping onto the next.

But to a writer, it turns more like a wheel.

It rolls out of darkness and catches you up, trapping you inside a circle for a year or 10 years, however long it takes.

You move around inside of it, back and forth, until finally it releases you.

Although it never really does, not entirely.

You could say a book eats a writer many times, you could say it eats itself.

In any case, to a writer, the idea of a beginning or an ending is absurd."

- To have written that essay back in 2003 on literary regionalism, it always was very much in conversation with not only the ground, you know?

The land or the people, but it also has to do with the history of the place.

"Most writers would've given up by now, but I've kept on seeking.

As a writer, I think that's what you do.

You keep peeling back, you keep whittling.

Eventually, maybe you find the right phrasing and then you move on to the next sentence and do it again.

The next sentence often changes something in the sentence before, and you have to go back and start all over.

Problem after problem, you try to solve it.

What is writing, but the solving of impossible problems?

Or like Suzuki said, "Nirvana is to see a thing through to the end.""

(feet padding) (gentle music) (no audio)

Video has Closed Captions

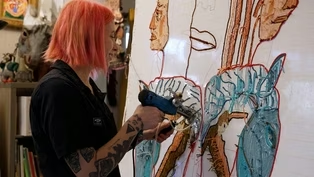

Clip: S27 Ep1 | 9m 18s | An edgy tufting artist wants to make you laugh and cry. (9m 18s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep1 | 7m 9s | Vietnamese American baker, Helen Hồng Nguyễn, bakes artistic cakes reflecting her heritage. (7m 9s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

Support for PBS provided by:

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB