Virginia Home Grown

Clippings: Protecting Our Watershed

Clip: Season 25 Episode 6 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Explore the importance of plants to our waterways!

Visit a VCU research center on the James River studying riparian buffers and wetlands restoration. Learn how bog gardens control runoff and recharge groundwater with the Albemarle Garden Club. Engage with us or watch full episodes at Facebook.com/VirginiaHomeGrown and vpm.org/vhg. VHGC 502.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Virginia Home Grown is a local public television program presented by VPM

Virginia Home Grown

Clippings: Protecting Our Watershed

Clip: Season 25 Episode 6 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Visit a VCU research center on the James River studying riparian buffers and wetlands restoration. Learn how bog gardens control runoff and recharge groundwater with the Albemarle Garden Club. Engage with us or watch full episodes at Facebook.com/VirginiaHomeGrown and vpm.org/vhg. VHGC 502.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Virginia Home Grown

Virginia Home Grown is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(soft entertaining music) >>We can think of wetlands as nature's speed bumps.

They slow water down before it gets to the receiving rivers.

They're also nature's supermarkets.

They produce almost more organic matter than any other ecosystem on the planet.

And they're also known as nature's bird bats.

>>In this time when we just have more intense storms, we've really been able to positively affect this area and keep the water here.

(birds chirping) >>Production funding for "Virginia Home Grown Clippings" is provided by viewers like you.

Thank you.

(soft entertaining music) (soft entertaining music continues) (soft entertaining music continues) Welcome to Virginia Home Grown!

Today we are thinking about the role that plants play in managing water in the ecosystem, including filtering pollutants, preventing erosion, and regulating water flow.

They protect our watersheds.

First, we're going to visit the Bog Garden at Booker T Washington Park in Charlottesville.

The garden is the project of the Albemarle Garden Club, and Amyrose Foll met with Dana Harris to see why this spot has become a favorite with so many in the neighborhood.

Let's take a look.

>>So we are in Booker T. Washington Park, and this is a microclimate wetland.

We in the Albermarle Garden Club refer to it as the Bog Garden because it's just kind of a sweet, fun name, but it is really wet, fairly stagnant.

And so if you had to step in there right now, you would probably sink about four inches and your shoes would definitely be wet.

>>Ah, it is magical in here because of the dappled sunlight and the shade.

It's really kind of a little oasis here in Charlottesville.

>>Yeah, it's a nice little quiet corner.

And in my time working in this garden, we've seen more and more people use it, which is lovely.

The city has created some trails around and so it actually has gotten much more used.

>>So tell me a little bit about the plants that you have arranged in here.

>>Yeah, so we really focus on natives and I would say there was a great deal of invasive removal that happened before any of these plants really took hold.

But as we've spent years taking out invasives, we've had good luck with planting plants.

We have a fern that's called sensitive fern, turtlehead.

There's a New York ironweed.

This is quite a grove of ostrich fern and there's some Joe-Pye weed in the distance.

We've never planted Joe-Pye weed in my time here of 10 years, but I think it's clearly happy here and has self-seeded.

>>It's great for the butterflies too.

What is that lovely splash of color that's in the center there and along the edge?

>>Yeah, that is cardinal flower and that really is quite spectacular this time of year, I think.

>>Of all of these plants in here, what's your favorite?

>>Well, right now you have to love the cardinal flower, right?

My opinion changes every time I'm here, depending on what time of year it is.

I would say in the spring, we have beautiful ephemerals, we have tons of woodland geraniums and blue bells, and, you know, that whole hillside is just covered with blue bells, which is really spectacular.

But this time of year, it's hard to think that it's much better it's hard to think that it's much better it's hard to think that it's much better than this cardinal flower.

We have to pay a lot of attention to runoff.

As you can see, you know, this beech tree here has had some erosion and we've researched and decided that lady ferns, which is the ferns you see here, are really the best that we can find to match the soil water and they really hold the soil quite well.

>>It's beautiful.

That is a majestic tree.

Absolutely wonderful.

So how long did it take you to get this established here?

It seems like a lot of work.

>>You know, it has been a lot of work, and while I'm the one standing here, it has been a real community effort.

The Albemarle Garden Club hosts a work day a month.

We have probably anywhere from like eight to 12 people work and the city supplies us with a tarp and we put all of our debris, any invasives on the tarp and they come and take it away.

So it's taken us about 10 years to really get this going.

And I would say we now aren't spending as much time on invasives and we're able to spend more time helping the community find ways to be here, helping school kids come and support field trips here and do things like that, which is really sort of another fun thing.

>>So what was the most challenging invasive to remove from this area?

>>You know, I think some of the, like, Japanese grasses, They've been really hard.

It was actually beautiful.

It was this very chartreuse-y green, but it has the oddest root structure and it has been virtually impossible to get completely rid of.

We are winning the battle, I would say.

These sensitive ferns have really helped as they've developed.

You know, these were just little tiny plugs.

So, you know, it's an ongoing thing, but we don't wanna spray anything in here that's toxic.

So we do just pull the weeds when we see them and hope that when we plant the natives, they just are able to fight off some of the invasives and that seems to work.

English ivy is also a hard one here.

It just doesn't even seem to matter that it's really wet soil.

You would think they wouldn't like to have wet feet, but they don't seem to care.

And I would say we also, unfortunately, are fighting the fact that in this park in the '70s, I have been told that Parks and Rec planted 7 to 8,000 plugs of English ivy to try to keep erosion at bay.

So we now know no one would ever do that, but at the time, that seemed like a good idea.

>>This is a pollinator hotel.

that you guys have built?

This is a big hit with the kids that come through here.

They love this, you can even see now Theres some... >>Its being inspected by something, yes!

It is, it is!

Some things!

And this was a project that the Albemarle Garden Club took on about eight years ago, and we had a great metalsmith guy come and build this structure and it was really quite an effort to get it into the ground.

>>So this is so beautiful.

What are the ecological benefits of this garden area?

>>Well, I think primarily because it is a microclimate wetland, it serves the purpose of slowing the runoff from higher elevations down lower.

It captures the water, the water gets into the ground table and doesn't run out into the street.

It's housing and food and water for bugs and creatures alike, and that is a benefit.

And I would say the water gets cleaner because these plants are here.

It basically supports all these plants.

>>So you mentioned community in the garden.

It sounds like you have a lot of great things going on and events here.

How can other people get involved?

>>So I think this park gets used a great deal.

We have spent our efforts on a couple of things.

We wrote a grant and received a grant from the Garden Club of America to host a community day here, which we've done the last three Octobers.

And that has really been, it's been called Down by the Bog and it's really been a family day, family fun day, intended to bring people to this place and to educate them.

We have frogs and little kids count the number of frogs in the bog and we've got all sorts of sort of just nature play.

And it's done in partnership with about four or five other non-profits in town.

And we've had as many as 300 people show up.

People from the Garden Club bring flowers from their garden and the kids make little bouquets.

And it's been a fun event and a great way to get people to learn about what is a wetland, why it's important.

We also are lucky that this site is within walking distance of five different public schools and it's used often as a science field trip.

And we've hosted second graders here to talk about pollinators, which has been really fun.

We've hosted seventh graders here to talk about water and ecology and climate change.

And so it's always fun to have young people move through this space and the questions that they ask and the things they're interested in are always sort of humorous.

>>That is wonderful.

Thank you so much for having us today, and thank you for sharing this beautiful garden with me.

>>Oh, you're welcome.

Thanks for having me.

The diversity of plants and wildlife in this special oasis proves even small wetlands can make a huge impact on the community and the environment.

And now, Doctor Robyn Puffenbarger has a garden tip to share on why adding a water feature to your garden is a great idea.

Be it a small fountain or a large pond.

(lively shaker music) >>Many of us who live in Virginia have a pond, a stream, lake, or other natural water source to enjoy in our backyard landscapes.

But many of us also live in small places or places that just don't have access to water.

And so one of the things we can do is bring water to our landscapes.

That could be a small feature, like a self-contained fountain or little pond system that you put on your deck.

You'd plug it in and have the sound of water, and that moving water might attract birds to your back deck.

You can also put a much larger pond in, like the one that's behind me, that's dug in, and then deep enough to support fish and plants.

This particular landscape is really enjoying a mix of sun and shade, and one of the things that's very flexible about water features is that they will do well in either spot.

Depending on how much sun you have, you may need to add water more frequently if you're in full sun and make certain plant choices to make sure that they, in the water and around your pond feature, will tolerate that full sun.

Like the water lilies, which have an array of colors to choose from when you're making purchases or finding them.

To cardinal flower, which is a Virginia native that is super deep red, pickerelweed, which is a light purple and also native.

Fish are a wonderful addition to a pond, giving lots of color and life.

But if you're not interested in having fish in the pond, don't worry, if you don't have them, both frogs and salamanders will occupy your space, laying their eggs.

They usually avoid places with fish because the fish are predators for them.

So you can have this natural landscape, natural creatures come in.

Once you have that water and sound, you're going to see mammals, like raccoons, opossum, and deer, if they're in your neighborhood, maybe drinking, which is a wonderful thing to see.

And if you make part of your water feature shallow, so not very deep, maybe just an inch or two deep, then you'll see your birds start to bathe and drink.

Most birds won't enter water that goes over their feet, they're very fearful of drowning.

So having that little spot where it's nice and shallow for your birds, you'll really enjoy getting to see them as well.

So water features have all sorts of added benefits for your home and garden landscape.

So think about anything from a very small, little fountain you could add to a much larger pondscape if you've got the space for it.

You'll really enjoy the sound of the water and all of the interests that it attracts.

Happy gardening.

When we think of water, we need to also think of plants.

Plants are key to reducing runoff, capturing pollutants, controlling erosion, and filtering water.

And now let's take a look at my visit to Charles City County to talk with Doctor Ed Crawford, the assistant director of the VCU Rice Rivers Center, about a successful wetlands restoration project and to see a unique waterway, a freshwater tidal marsh.

>>Back in 1927, this creek was dammed by a gentleman named King Fulton to create a duck pond and a fishing habitat for Berkeley Plantation.

And in 2010, with the help of the Nature Conservancy, American Rivers Organization, NOAA, and the Army Corps of Engineers, we were able to remove the spillway of the dam, and recreate about 70 acres of tidal wetland and a few acres of non-tidal wetland.

>>The Rice River Center is a wonderful resource for your students.

It provides lots of hands-on learning.

So, tell me about that.

>>Sure.

Our focus is on the science and management of large river ecosystems, their watersheds, their airsheds, what goes on above the surface of the water, but also what goes on below the surface of the water, including water quality and air quality.

And it's a place where we can train the next generation of environmental scientists, conservation biologists, and restoration ecologists.

>>And I love the location because I mean, you've got the James River right there, and you've also got now Kimages Creek, which is freshwater, and the James, of course, is brackish and tidal out there.

So this area here is actually a very unique ecosystem that we're sitting in.

>>Absolutely.

So we're at the head of the tides here on the James River estuary, since the tides push all the way up to the city of Richmond.

What makes us unique is that it is tidal freshwater here.

So if you dip your finger in the creek here and take a little sip, it's gonna be fresh.

I wouldn't suggest doing that.

>>No, I'm not planning to.

(Peggy laughs) >>And that makes us a geo-morphologically unique site, because there's lots of work done down in the brackish marshes and salt marshes, and there's lots of work that's being done up in the unidirectional flow of the James.

>>Right.

>>But there's not a lot of science that's done on tidal freshwater wetlands and tidal freshwater ecosystems.

And they're some of the most imperiled and important ecosystems in the world.

And one of the things we did with the help of the Nature Conservancy and American Rivers, was plant about 25,000 aquatic trees and shrubs.

We've planted bald cypress, we've planted river birch, we've planted sycamore, we've planted dogwoods and species like that.

Buttonbush.

A lot of common species that you'd find in aquatic habitats.

They're uniquely adapted both physiologically and morphologically and anatomically to live life in saturated soil conditions.

>>Yeah, I was gonna ask you about that.

What makes a plant capable of living in wetland?

'Cause I know at my house, with all the rain that we've been having, I've been losing a lot of my plants, 'cause they're just saturated.

They can't handle the wetness.

>>Every cell in a plant body, like every cell in the human body, has to have oxygen.

And so even the plants that can grow in water still have to have oxygen in their roots.

So they have these unique features.

It forms what's called aerenchyma tissue.

>>Yes.

>>And that enables a plant to act like a straw from the sediments up to the atmosphere, or from the atmosphere down to the sediments, so they can literally transport oxygen from the above ground chutes down into the roots.

And that's the primary adaptation that many herbaceous and woody plants use in order to get oxygen back down to the roots, so they can carry on their metabolism.

>>In that very wet area.

But not all plants have that adaptation, kind of like in our rain gardens.

>>So in a rain garden, you're gonna wanna put a specific subset of the plants that are out in the environment.

And this subset, of very few plants, actually, out of 22,500 plants that are in North America, are adapted to living life with their roots in saturated anoxic conditions.

>>Uh huh.

>>So if they don't have these unique adaptations, they're not gonna be able to survive in the rain garden.

Many woody species have lenticels that enable gas exchange between the cambium and the outside air.

But in a wetland plant, they're gonna have what's called a hypertrophied lenticel.

So they'll be enlarged in order to help bring air in.

Some of the other adaptations of woody species are shallow roots, adventitious roots, which will form what's also called water roots.

And they'll form if flooding occurs for several weeks or a month, they'll get roots that actually grow not from embryonic root tissue, but out of the stem or the trunks of the trees.

>>Right.

'Cause those cells can differentiate either way.

>>And since when you're dealing with a rain garden or with a wetland and you have saturated soils, plants aren't gonna be able to put a big taproot down too far in the water.

So their plant roots are gonna spread out along the surface to help capture oxygen, but also to help support the tree.

>>Mhm.

>>Ane other interesting feature of wetland trees at least, is the big, flared buttress at the trunk of like cypress trees and tupelo trees and some of the ash trees.

That buttress is like a flying buttress on a medieval church.

It helps support the tree and give it structural support in a habitat where they can't put down big tap roots.

>>It's fascinating, because people are always still wondering what about those knees with the cypress?

And I guess one day we'll know the answer.

(Peggy laughs) >>Well, there's a lot of theories out there, but I think the theory that has the most traction right now is that it's for structural support.

So they spread out and kind of form a little bit of a tiny ecosystem of their own, but it's all for structure to help with tree support in an area where they can't put down a big taproot for anchoring support.

>>Mhm.

And speaking of ecosystems, those trees themselves created their own ecosystem, but the plants all together bring in and enrich, I'll say the wildlife in this community.

>>Oh, absolutely.

You're sitting right now in an ecological success story.

When their dam was here, we had a handful of different fish species that used this site.

Dozens of birds maybe, but once we removed the dam and then restored these wetlands, we've got dozens upon dozens of fish species that are using the site, over 153 different species of birds.

It's hopping with frogs, it's teeming with toads, lots of reptiles and amphibians.

It's a real biodiversity hotspot these tidal freshwater wetlands are.

>>And it all starts with the plants.

>>Right, yeah.

>>The plants.

It rolls back to the plants.

But how many types of plants do you think?

I know you know, how many are growing here.

>>Well, we found 50- >>In Kimages Creek.

>>55 different species of herbaceous plants, and they include perennial grasses such as southern rice cut grass, and annual grasses, such as the northern wild rice that you see right here that's growing.

This is the same wild rice that has sustained the indigenous populations around here for thousands of years, and continues to do so in the Midwest.

We have broadleaf perennial plants like the Pontederia cordata, the pickerelweed and blue flower you see behind us.

We have broadleaf annual plants like arrowhead.

And then there's a host of woody species as well.

We've got cypress, you've got lots of shrubs, and all kinds of woody species of vines that use the site as well, so it has really become an amalgamation of species diversity.

And while the site receives tides like a salt marsh, so it's getting the same subsidies- >>Right.

>>Without the salinity.

So without that salinity, it enables the biodiversity of plants just to explode here, which it really has done.

>>It's fascinating.

People just don't realize the diversity that a wetland provides.

>>Oh- >>And we have forgotten the importance that they play.

And I think here that, you know, this example of taking a lake, removing the dam, and restoring it back to a wetland is one that we can repeat up and down our rivers here in Virginia, and elsewhere along the East Coast.

>>Not only Virginia, but all but all over the country.

I mean, we actually lived in a "dammed nation."

There's over 2.5 million dams, supposedly.

Low head dams and larger dams across the country.

And it is a viable option now to help restore not only stream habitat, but also the riparian wetland habitat.

Help out with cleaning our surface water, with cleaning our groundwater.

>>Yes.

>>And help out with ameliorating the climate, because that's another thing that they do.

They sequester carbon, they help with- >>Tremendous amount of carbon.

>>Yeah, absolutely.

>>Ed, I thank you.

I thank you for really getting down and dirty with wetlands and explaining this.

And for the research that you and the students are doing here at the Rice River Center in Kimages Creek.

(birds chirping) the Rice Rivers Center is an amazing living laboratory for research, restoration and education, primarily focusing on the James River watershed.

Their work flows beyond the river to influencing public policy.

Next, Randy Battle has some tips to share for starting seeds and using water in the garden responsibly.

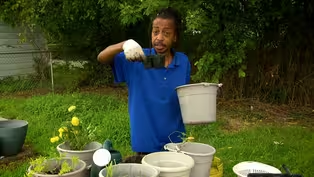

(light percussion music) >>You can grow your garden 365 days a year, but one of my favorite times of year is the summertime because you can grow all different types of crops.

Today what we're gonna do is start some seed starting mix, and I'm just gonna show you how I make my own seed starting mix using some old soil that I had from previous years.

And this particular soil right here, as you can see, I'm just taking it right out of this container, uh, uh, okay?

And we're just gonna put it into the sifter, right?

And I have a sifter just for my garden.

And what I like to do is take my sifter, and I take a regular old container, and I wanna sift it just like so.

(soil rustling) You can just sift it just like so as if you're cooking or if you're making something in your oven.

But yeah, I love to make my own seed starting mix.

And what you will get, you will see (soil rustling) how nice and soft that soil is.

And what I like to do is just take a seed starting container, (soil rustling) pour my homemade seed starting mix in there, okay, okay?

(soil rustling) Yeah, we take what we have and make it work.

And then you wanna take just a seed.

These are some green beans.

I'm just gonna drop the seed right into the container and take a little bit more of my seed starting mix and pour it right over.

It's not rocket science, you guys.

Make it fun.

Make your garden fun.

Watering is one of the most important things that you wanna pay attention to.

You don't want to over-water and you don't want to under-water.

One way to find out if your plants need water or if your soil is dry is use the finger test.

And what I like to do is just gently take a finger and push down into the soil.

You will feel if it's moist or if it's dry.

If it's dry, add a little water.

If it's moist, you should be good to go.

I like to water around my root system instead of pouring water directly on the leaves, because if you do that, you can get a lot of fungi, and mold, and pests.

What I like to do is take my time and sprinkle a little bit here and there, use my finger stick to make sure it's moist, okay, okay?

Live, love, laugh, grow stuff, and eat it.

From our gardens to our wetlands.

The choices we make flow into our waterways.

As the built environment expands.

We need to promote sustainable practice.

Is to maintain this delicate balance.

Thank you for watching.

We hope you will think more about your gardens role in the ecosystem, and the water that moves through it.

See you soon.

And until then, remember, gardening is for everyone and we are all growing and learning together.

(light percussion music) As the temperatures rise, so does the stress on our lawn.

And many people ask, what step can I take to reduce the stress on the lawn?

And it's a simple answer.

It's just raise the mower blade, raise it to about four inches.

Having a taller lawn will enable the roots to grow deeper.

Plus it'll shade the soil which will actually retain soil moisture and reduce the germination of weed seeds so that one simple step raise that mower blade to four inches will make all the difference.

In a healthy lawn.

Happy gardening.

(birds chirping) >>Production funding for "Virginia Home Grown Clippings" is provided by viewers like you.

Thank you.

(gentle upbeat music) (chime)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 7m 52s | Discover native plants that thrive in wetlands (7m 52s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 6m 28s | Discover why healthy forests improve water quality in streams and rivers (6m 28s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 5m 32s | Learn identifying characteristics for common amphibians in Central Virginia (5m 32s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 3m 3s | Create a homemade seed starting mix and get waterwise gardening tips (3m 3s)

Water Features for Home Landscapes

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 2m 57s | Discover the benefits having a water feature in your garden (2m 57s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 8m | Learn how a dam removal project created an ecological success story (8m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Home and How To

Hit the road in a classic car for a tour through Great Britain with two antiques experts.

Support for PBS provided by:

Virginia Home Grown is a local public television program presented by VPM