Oregon Art Beat

Earth Archive

Season 22 Episode 12 | 28m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

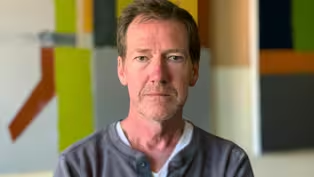

Abstract painter Tom Hausken; Artist Judy Hoiness; Photographer Jim Fitzgerald.

Ashland-based painter Tom Hausken explores time and space in his exacting abstract paintings. Long-time Bend artist Judy Hoiness paints and uses recycled materials to make her abstract landscapes inspired by her love of the Northern Great Basin. With his hand-built large format camera, photographer Jim Fitzgerald gets lost in the magic of creating carbon transfer printed photographs of nature.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Art Beat

Earth Archive

Season 22 Episode 12 | 28m 51sVideo has Closed Captions

Ashland-based painter Tom Hausken explores time and space in his exacting abstract paintings. Long-time Bend artist Judy Hoiness paints and uses recycled materials to make her abstract landscapes inspired by her love of the Northern Great Basin. With his hand-built large format camera, photographer Jim Fitzgerald gets lost in the magic of creating carbon transfer printed photographs of nature.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Oregon Art Beat

Oregon Art Beat is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for Oregon Art Beat is provided by... and the contributing members of OPB and viewers like you.

[ ?

?? ]

MAN: I'm bringing time back with me, time that I spend out in nature.

WOMAN: It's in my art.

I can't help it.

It just comes out.

I love my state, I love the land that forms, and it just evolves in my work.

MAN: The trees many, many years ago took roots in my heart.

It's what I was meant to do.

Oh, yeah, that's gonna work.

I believe that there is energy in everything that is around you: the trees, rocks, this wall, the floor.

And listening to that gives you information, allowing it to vibrate through you.

And that's the kind of energy I want to bring to the painting.

I want tension there.

[ ?

?? ]

Something that I'm exploring in the work right now is madrone trees.

And so I wanted to bring a hint of those colors back into the work and then bury them under larger plains of what would be sky or cloud or smoke.

Something I want to try to achieve in the painting is this action, like all the intensity of these little, smaller shapes, and then surrounded by a bigger field of color.

I'm not trying to accurately portray this thing.

It won't look like a beautiful clump of madrone trees.

But it'll be there.

Sometimes I'm actually bringing a few physical things back: a leaf or a piece of bark, something like that.

But I'm bringing time back with me, time that I spend out in nature.

My paintings are pretty thick, and they're full of lots of information and layers.

[ ?

?? ]

There's sometimes 15 or 20 layers of paint, and all of that takes time to develop, so I'm installing that time in the painting.

I painted an edge here with my straight edge, and then I brushed below it.

I wanted to allow that information to be seen through.

Not only is it three-dimensional, but you see -- you can see back to those earlier layers, those earlier decisions.

One of the most powerful things in my paintings is where two fields of painting come together and where they briefly touched or don't touch and all the information that lies directly underneath where these edges are.

I think it's at these edges in the painting and in our lives where stuff really happens... where you're pushing out into the world, into the unknown.

Mostly I love just applying the paint, mixing the colors.

That's what I really love about painting.

I like the stuff of it.

I like buying tubes of paint, I like opening them and squeezing it out and mixing them and smooshing it around.

I like the smell of it.

I like pencils and straight edges and scissors and knives.

And all of that stuff is potential.

And it's fun to use.

[ ?

?? ]

My parents and my grandparents, they were very much into materials.

My grandmother was an amazing gardener, and my mother could sew, and that was cool to me.

When I got into art school and started moving pigments around, I kind of found the thing that I wanted to play with, the materials that I wanted to create things with.

I guess for me I am trying to create pleasing shapes and relationships in a composition that feels complete and powerful.

I want this band that's starting here to be there, and there it is.

And then on other levels, I'm trying to talk about a fragile relationship that I have with my environment, which can be a difficult subject to talk about as you see the degradation, the fires that come through, the long droughts and the changes in our environment.

But within the context of the painting, there's a beauty and a struggle that I think is worthwhile.

[ ?

?? ]

When people look at my paintings, I hope that they just can stand still for a moment and let the painting try to speak to them.

I think you can gather a lot of information from listening and from being silent... and allowing, I'll say, the spirit of what the painting is to manifest.

You need to approach a painting, give it time to open up to you.

Oh!

Oh, throw away some of these really old, rusty tools I put with it just to -- and no plan to that.

Whoa.

Oh, wow, that's beautiful.

You can't plan this.

[ ?

?? ]

What you get is what you get.

I always wanted to be an artist.

I mean, I didn't really think down deep I'd probably be one, but I always had the desire and the urge and the willing to dedicate myself to it.

I'm looking at the rust designs that you can even see a part of a pair of scissors and a wrench.

A friend in Sisters buried some fabric and then dug it back up, and I thought it was the most beautiful piece of fabric I'd ever seen in my whole life.

Putting in some soap, vinegar, and salt.

Every little edge was just gorgeous.

So I decided, ''I'm gonna do that.''

People think it's a little crazy that you would go through this, but you cannot find any piece of material that would look like that if you didn't go through this process.

You cannot design it yourself.

The nature, the ground is so wonderful because things grow up and they're beautiful, but underneath, when they go down, they start decaying, and that's an interesting process too.

Now, there is some risk that I might lose some of the things that happened on here, but I'd rather have it stop decaying.

And since I'm getting a whole bunch of designs I hadn't even planned on...

I think I heard this quote once, and I think it was by Louis Armstrong, it says, ''The cats I like best are the cats that take chances.''

And I thought, ''Wow, that sounds really great.''

That's what I like to do.

What -- oh, this looks like a fi-- oh, yes, it does.

It is a file.

You can see the grain of the file right here.

Isn't that cool?

That's really fun.

[ ?

?? ]

My work has evolved over the years from fairly realistic -- as realistic as I would ever want to get -- to fairly abstract now with some hints of realistic shapes inside.

I use a lot of organic-type shapes and organic-type colors in my work today.

Recently I started branching out into using textiles, especially vintage fabrics, in my drawings and paintings.

I'm doing a series of little girls' dresses.

Where I live in Bend, we're right on the edge of the northern part of the Great Basin, and the pioneers passed through that area too, so that's another thing I'm thinking about: What were they thinking, what were they doing, and what kind of things did they leave accidentally?

I'm painting on and tearing and ripping and sewing and making a new dress out of just scraps.

To me, it represents a child had something brand-new, and then as the child lived and went through the Great Basin into Oregon, the dress becomes torn apart, maybe a little piece gets snagged.

I'm the inventor of all this.

That's the part of my Great Basin series, it's called ''The Great Basin: What Is and What Might Have Been.''

I'm really enjoying, though, what might have been.

[ ?

?? ]

So right now I'm really into using fabric and paint and paper combined.

All this, I was never, ever taught to do, so I'm learning these things, and I love to take risks, so who knows what can happen.

This pattern here, I've not really done that before with my machine.

I kind of really like it.

I like what's happening.

Reminds me of the rocks and some of the forms out there in the Great Basin.

I've had a quest for the last four years to find this one particular area, and I did.

[ ?

?? ]

It's a long, hard journey, but you know what, it's really fun, because you get to see all the wildlife, the trees, the rocks in this discovery of finding the pictograph.

We're just finding so many varieties of shapes and figures, and, oh, even some almost like tally marks.

The figures are very gestural, like...

I love that beautiful shape.

I don't want to copy these, because that's -- this is another artist's work, and they should be respected, so I'm just getting inspiration and my own interpretations.

The fabric that I use, it's pretty rumpled and crumpled and not ironed, and to me it represents the rock shapes that the pictographs were on.

This is a great little composition right here that I will store here and go back and work on.

[ ?

?? ]

I'm a recycler, and I'm also a collector of, as you can tell, old things.

And so I thought, you know, instead of buying new fabric, why not try to recycle whatever I can find?

Oh, my gosh!

There's wedding dresses.

Look at the wedding dresses!

Here you go.

Oh, thank you.

I think it might fit me.

[ chuckles ] When you look at pieces that have stains or tears or patches where somebody has very painstakingly sewed a patch, it also holds so many memories.

Why can't I give it another life?

Oh, this is interesting.

It has a little bit of cut work in it.

Got some really great things.

This linen-cotton blouse, isn't that gorgeous?

Ooh!

I never see these very often.

My great-great grandfather came to Oregon on a cattle drive, liked it so well, went back and got his family.

So I'm fourth generation.

My grandkids are sixth-generation Oregonians.

It's in my art.

I can't help it.

It just comes out.

It's what I am.

I love my state, I love the land that forms from east to west, north and south.

And it just evolves in my work.

The Great Basin, I'll probably be on that project for the rest of my life.

I can't get out of it.

I don't think I could get out of it.

I mean, I could never explore every square inch in my lifetime.

And every time I go out, I get great ideas, I go out a little bit farther, more ideas.

So that opens a whole new world.

[ ?

?? ]

[ birds chirping ] I want to make sure that I get some separation between these trees here.

Oh, yeah, that's gonna work.

When I was young, my father would take the family to Yosemite and up into Oregon, and we'd go on vacations in the trees.

The trees many, many years ago took roots in my heart.

And it's my main subject matter.

It's just something I absolutely love.

My name's Jim Fitzgerald.

I'm a large and ultra-large format film photographer and carbon-transfer printer.

[ ?

?? ]

I specialize in a very historic process that was developed in 1864.

You make a hand-made one-of-a-kind print that's the most archival print that you can create.

About 13 years ago, almost 14 years ago now, I was able to see my first carbon-transfer print in the flesh, and I knew in that instant it was a life-changing experience.

And to this day, I have done nothing but print carbon transfer, and that's all I'll ever print.

They're the most beautiful prints that you can ever imagine.

It's what I was meant to do.

I've had some wonderful moments with light, and Mother Nature has given me tremendous gifts over the years, and being able to produce that in a carbon-transfer print is really something that helps me express how I feel deeply inside.

It was actually perfected in 1864 by Sir Joseph Swan out of England.

And there's no chemical in there, nothing that's going to hurt it.

It's hardened gelatin.

It will last 100 lifetimes.

It's why it's the most archival print you can make.

You can make something that will outlive all of us.

So I was drawn to that fact.

Back in 2007, when I had just started carbon-transfer printing, I spent a day in Yosemite Valley, best photographic day of my life, and it started a life-long project documenting the black oaks in Yosemite Valley and how fragile they are and how they're fighting for their survival.

And then I just started working my way east along this trail, and I found imagery that nobody else to my knowledge was seeing.

[ ?

?? ]

Every time I go out in the field, Beethoven's playing in my head, so I am in another world.

It allows me to open up my senses, and I don't even know where I go.

I have the entire collection of Beethoven.

It's all in my head.

I finally shot my last sheet of film, and I stopped, and I'm like, ''Where am I?''

I was just in such a zone and I realized at that moment, ''I need to present this.

I want to do a book.''

So I learned how to book bind.

I took original prints and printed them on fine-art watercolor paper, and I developed a process to be able to print text in carbon transfer and incorporate it into the book.

So the first book, Survivors I, is basically my journey of that day and my feelings for the imagery in the book.

I love going back to the same areas and seeing how the light has changed, how the environment has changed, how the scene has changed.

Sometimes some of the trees that I love are gone, sometimes they're still there and they're in a terrible state and might be gone before I come back the next time.

And I look at it as a gift that I'm able to record these before the process of life takes over.

I've always had a love of woodworking.

You think about cameras that were built in the late 1800s, 1900s, they're all built by hand, so how hard can it be?

I copied an old design, and I made a beautiful 8-inch by 20-inch camera.

Took me 18 months to build it.

As I look back on it into camera-building's a lengthy process, exposures are lengthy exposures, the hand-made print is a lengthy experience.

What turns a lot of people off is there's so much time invested.

We're in a society where everybody wants instant results.

But as an artist, any artist, I would think, is working to produce the best that they can, so for me it just happens to be carbon-transfer printing, and it takes a little longer to do.

We couldn't have timed it any better.

So I got a phone call out of the blue, and I'm like, ''Okay, who is this?''

Got a spot.

This is it.

Logan Clark, he's just a really, really wonderful young man.

This is a good spot, the way the backlight's coming and hitting everything over here.

Well, the cool thing is, you just wait 10 minutes, and it's going to change.

Oh, yeah.

He saw some of my work out at the LightBox Photographic Gallery in Astoria, Oregon.

It was a group show, and he just had this print downstairs about, you know, 8 x 20, Merced River frozen, it was just amazing, and I just looked at it and I go, ''Oh, my God!''

You know, ''I need to learn how to do this.''

JIM: You just follow the shadows, and the shadows will pull you right into the image.

I gave him the basics of how everything's done.

No secrets.

And he took that ball and ran with it.

I couldn't be more proud of what he's produced.

LOGAN: You spend five minutes with this guy, and you're gonna know how passionate he is.

I mean, when he's photographing, when he tells you there's Beethoven in his head, it's real.

[ laughs ] [ ?

?? ]

JIM: This just has an old-world feel to it, and the lens I use on it helps to capture that feeling.

[ shutter clicks ] Having Logan as the tour guide, so to speak, he had mentioned Lucia Falls.

And there were so many beautiful little pockets and areas that were visually stunning.

I saw this little forested area kind of off to the left of the trail.

It was a little micro-climate all by itself, and it was a young forest, it was evolving, and I thought, ''Wow, this is just a story waiting to be told.''

Oh, yeah, this is like epic.

I'm just going to get another meter reading.

That's been a favorite spot of mine, because there are so many different ways to interpret that little forest that I know I'll be working that for a long time to come.

All right.

I always pay homage to Mother Nature.

And it may not be vocally, but mentally I'm always thanking Mother Nature for the gifts that she gives me.

You need to interpret the way you feel about that image yourself, which I find I love that.

And generally that feeling of melancholy, soft-focus, old-world style seems to resonate a little bit more with me than the very sharp imagery.

So, what I'm doing here is to see how much pigment is still coming off.

You can see pigment running down here.

Let me stick it back in the water for a little bit.

The wonderful thing about it is, if you get everything right, you can develop a textured relief print, which is very unique to this process, and that is because the gelatin melts away less in the shadow areas and more in the highlight areas, so you have a three-dimensional relief.

So this a very thick area, this is a very thin area, because basically you're developing away almost to paper white.

When you get it right, the prints have depth and a feeling of uniqueness that is very hard to describe.

Once that gelatin dries, you have nothing environmentally or chemically that will harm that image for its lifetime.

It's permanent.

So if you make a good print, it's going to be around forever.

If you make a bad print, it's gonna be around forever as well.

[ ?

?? ]

For me personally, I like to keep my art form as close to the purity of the way it was back in the early days.

There's no going back once you click that shutter.

And more people are getting into it, and that's great, because we're going to keep it alive.

Look at the glow on the moss up there in this tree.

LOGAN: Wow.

You know, it just comes alive.

Brings that warm glow.

I know you like the falls, but you know me, trees are in my heart, so it's like... LOGAN: We have a great friendship, and I sure appreciate all he's given me.

And I plan on taking that torch, you know, when it's my time and someone knocks on my door.

And that makes me so happy to know that I've passed along something that I absolutely love to somebody younger, a different generation that's gonna help keep it alive when I'm gone.

And that's really special to me.

To see more stories about Oregon artists, visit our website... And for a look at the stories we're working on right now, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

[ ?

?? ]

JIM: Oh, yeah, this is like epic.

Support for Oregon Art Beat is provided by... and the contributing members of OPB and viewers like you.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S22 Ep12 | 11m 28s | Jim Fitzgerald builds his own large format cameras and creates photographs of nature. (11m 28s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S22 Ep12 | 8m 19s | Long-time Bend artist Judy Hoiness uses recycled and found materials to create her art. (8m 19s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S22 Ep12 | 7m | Profile of Ashland abstract painter Tom Hausken. (7m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB