Special Programs

Eclipse History

Clip: Episode 20 | 5m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

Scientists use eclipses for discovery and to prove their theories.

Scientists use eclipses for discovery and to prove their theories.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Special Programs is a local public television program presented by WCMU

Special Programs

Eclipse History

Clip: Episode 20 | 5m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

Scientists use eclipses for discovery and to prove their theories.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Special Programs

Special Programs is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Narrator] The oldest surviving record of an eclipse comes from Yin, an ancient capital city in China.

It was carved on a tortoise shell.

Three flames ate the sun, and big stars were seen.

A lot of ancient stories from the Americas to Scandinavia to India refer to the sun being eaten.

People thought some deity was angry, or these were omens that meant a king would die.

And some of those kings were nervous enough, they appointed people to study the sky and take lots of notes.

What started out as fearful fascination turned into something more scientific.

Freaking out about eclipses kick-started astronomy.

One of these early astronomers, Hipparchus used an eclipse to calculate the distance to the moon.

There was a total eclipse in his hometown, but he heard that 600 miles due south, only four fifths of the sun was obscured.

That was all he needed.

See, Hipparchus was all about this new kind of math involving lots of angles and triangles.

He calculated that the moon was between this far away and this far away.

This was hundreds of years before telescopes, and we'd already started to measure the solar system.

By the 17th century, the moon's size and distance were well known, but no one knew why the moon orbited earth.

Then a real oddball named Isaac Newton figured out the law of gravity.

But some people needed convincing.

Newton's hype man, Edmund Halley, that guy they named a come after said, "okay, Newton's law of gravity determines the moon's orbit so I should be able to use that law to predict exactly when the moon will go in front of the sun."

He calculated that an eclipse would hit Britain at 9:05 AM on May 3rd, 1715.

And he printed up these handy posters that reassured everyone, no, the king isn't going to die.

Halley got impressively close.

The sun went dark at nine sharp, and that eclipse proved Newton wasn't crazy.

He was a genius.

People went on to use Newton's ideas to accurately predict the orbits of most of the known planets.

But two planets had unexpected wobbles, Uranus and Mercury.

In France, tireless mathematician Urbain Le Verrier used lots of equations to show that it must be the gravity of unknown planets pulling Uranus and Mercury off track.

He calculated exactly where the planet pulling on Uranus would have to be.

And when astronomers went to look, there it was, they named it Neptune.

Le Verrier was psyched, and he was so sure they'd find a planet pulling on Mercury too.

He preemptively named it Vulcan.

But here's the problem, Vulcan was supposed to be right here just hidden by the sun's glare.

Vulcan hunters would need an eclipse.

Every time one rolled around, scientists including Thomas Edison scoured the sky.

But those eclipses never revealed Vulcan.

It just wasn't there.

Mercury's wobbly orbit remained a mystery until Albert Einstein came along.

Einstein had this radical new theory, the general theory of relativity, and indeed Vulcan unnecessary.

According to the theory, Mercury was thrown off course because the sun's bulk was warping the very fabric of space time.

Einstein's equations predicted the wobbly orbit perfectly, but as always, some people demanded more proof.

And once again, an eclipse came in useful.

In 1919, the darkened skies allowed scientists to see stars near the sun.

And just as Einstein predicted, the sun's huge mass nudged the starlight off course.

Those results made him an instant celebrity.

(camera shutter clicks) (soft music) During the solar eclipse, you can see the sun's fiery atmosphere.

Here's the reddish chromosphere.

In 1868, scientists studying the light of the chromosphere found evidence of an unknown element.

They named it Helium after the Greek sun God, Helios.

It took another 27 years before someone discovered Helium on earth.

Where the chromosphere ends, the feathery Corona begins, it sends blasts of charged particles into the solar system, and these space storms can take out electronics on Earth.

They could even potentially kill interplanetary astronauts.

So how does the Corona work?

Well, there's a lot we still don't know, partly because we can really only investigate it when something blocks the overpowering brilliance of the sun's disc.

We've built advanced instruments to try and do that, but the moon still does the job much, much better.

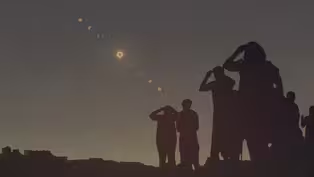

That's why even after all these years, scientists still flock to eclipses, point their gadgets at the sky and make the most of that brief moment in the moon shadow to shed new light on the sun.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep20 | 5m 1s | CMU Professor, Dr. Ari Berk, describes how different cultures interpret eclipses. (5m 1s)

Eclipse Preparation with Scout Troop 366G

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep20 | 3m 59s | In Saginaw, Scout Troop 366G prepares to view the eclipse. (3m 59s)

Video has Closed Captions

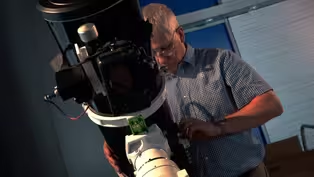

Clip: Ep20 | 3m 3s | CMU Professor, Dr. Axel Mellinger, shares his passion for astrophotography. (3m 3s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep20 | 7m 58s | CMU Professor, Dr. Aaron LaCluyze, describes viewing a total eclipse. (7m 58s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Special Programs is a local public television program presented by WCMU