Special Programs

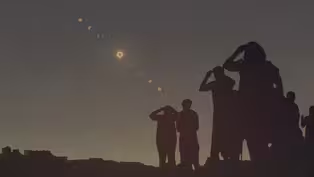

Eclipses: Viewing Totality

Clip: Episode 20 | 7m 58sVideo has Closed Captions

CMU Professor, Dr. Aaron LaCluyze, describes viewing a total eclipse.

Central Michigan University Professor, Dr. Aaron LaCluyze, shares his previous eclipse experiences and describes what viewers can expect during totality.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Special Programs is a local public television program presented by WCMU

Special Programs

Eclipses: Viewing Totality

Clip: Episode 20 | 7m 58sVideo has Closed Captions

Central Michigan University Professor, Dr. Aaron LaCluyze, shares his previous eclipse experiences and describes what viewers can expect during totality.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Special Programs

Special Programs is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- You kind of have to get 'em at just the right time, just the right moment.

So in truth, there's only a couple of times of year that are conducive to having eclipses at all.

So that's why we don't have an eclipse every month.

Like you would have a lunar eclipse and a solar eclipse every month, that doesn't work out that way.

It's kind of just two times a year that it's a chance for an eclipse but that doesn't guarantee that you have the eclipse, and it also doesn't guarantee you're in the right part of the globe to have that eclipse.

So what's exciting about this one is it just so happens that the sweet spot is here in the US.

- [Interviewer] Yeah, absolutely.

So talk about the path.

Where is it supposed to go?

- Right, so the path that we're gonna see, and it's not everybody in the US is gonna get to see it.

Like I said, it is a relatively small path.

There's gonna be a stripe that kind of stretches from down in Mexico up through Texas, but it cuts up through kind of southern Indiana, Northern Ohio, and then heads out to the east coast or so.

So here in Michigan, unfortunately, we will not see totality.

Totality is just south of us and as much as it pains me to say such things, my best advice for my fellow Michiganders is go to Ohio.

Here in mid Michigan, we will see a partial solar eclipse.

So part of the sun will be blocked out by the moon, but not all of it.

So totality, it's really just kind of a narrow stripe.

And even in totality, you get kind of a small window for that.

So from start to finish for a solar eclipse.

So the moment the moon starts to just barely get in the way of the sun until it goes fully away from the sun on the other side, that kind of path takes about two or three hours from start to finish.

But totality itself, like the moment, like the cool stuff that we're gonna talk about, that only lasts a couple of minutes, like the maximum it can possibly last, I think is about seven and a half minutes.

So it is a very, very brief window, but it's an astonishing window when you see it.

Now, what's interesting about a total solar eclipse, prior to totality, as the moon is starting to block out the sun and you've only got 80 or 90% covered, it's dangerous to look at the sun.

You've gotta wear like eclipse glasses, which we had those, you know, back in 2017 when that solar eclipse happened.

Everybody talked about getting eclipse glasses.

Or you can get special solar filters for a camera, or there's special kinds of welding glass that you can use, but make sure you have the right stuff.

But you need that to look at the sun safely.

But once totality occurs, the moment you actually cover up the central disc of the sun, you can actually look at it with the naked eye, but only, and I stress, only during totality.

So a couple of seconds before or a couple of seconds after is not good enough.

You've gotta nail it, right?

And that experience is, it's really an odd experience.

I'm gonna try and describe it.

It's hard to describe unless you actually experienced it.

- Right because you actually went to see the last total eclipse.

So yeah, share with us your experience.

- You know, I've been an astronomer for over 20 years.

I'm in my mid forties, and I had never seen a total solar eclipse with my own eyes.

I'd seen pictures and textbooks, I'd seen pictures online, and I'm like, "oh, that's kind of neat.

I'm sure they're using some kind of special camera technique to show what that looks like."

That's what I thought.

Even as a professional astronomer, that's what I thought.

But in 2017, I had the opportunity to see the total solar eclipse.

Now, it didn't come near Michigan, that one either.

And I have family down in South Carolina.

So I went down to visit them, and I got to see totality.

It is like words are inadequate, wholly inadequate to describe what it's like.

When totality occurs, it kind of feels like you're wearing like a special pair of sunglasses that has a little dial on the side and somebody's cranking it up and making it darker and darker and darker as time goes on.

But everything else looks normal.

Like shadows are nice and sharp and distinct.

Unlike at sunset, when the sun goes down, shadows get really diffuse and long and then go away.

And it's a very gentle passage into nighttime.

With the eclipse, that's not what happens.

It gets really weird.

You actually start to feel, or at least I personally started to feel a little bit anxious, a little bit uneasy, because the light's not right, for lack of a better word.

And so it gets darker and darker and darker.

And then the wildlife starts to react as if it's twilight 'cause it's getting darker and darker.

And so all of the insects that come out at twilight, like I think at the time we had some like crickets and cicadas, you know, those sorts of things, the insects that make noises at night at twilight, and then all the birds that feed on those insects came out.

And then in the modern era, we have all these streetlights that aren't on a timer.

They're on a sensor.

And that sensor saw everything getting darker and darker and darker.

And so all the street lights turned on, and then in every direction you looked, it looked like twilight.

You know, when the sun sets, you get that kind of red or orange haze kind of in the direction of where the sunset is, but the sun's up there and every direction looks like that because you're now in the shadow of the moon as it comes.

And so it was really, really strange.

And at the time, I'm an amateur photographer in my spare time, and I promised myself, I'm not going to experience the eclipse just staring through a camera.

I can't do that to myself.

So I set a timer on my watch and I said, "I've got 30 seconds to take pictures, and then I will not touch the camera."

And so totality happens, and everybody around me is just freaking out.

I take my pictures for 30 seconds and my watch beeps and I stop and I look up, and it's hard to describe what you see.

So the sun, we tend to think of the sun as just that disc on the sky.

But it's not, there's more to the sun than that.

On kind of outside of that disc that we see, which that disc is called the photosphere, just in astronomy parlance, it's literally the sphere that the photons come from.

So photosphere, so that's what our eyes normally see is just that photosphere and it's very, very bright.

But once you cover it up, you can see the outer edges of the sun, a thing called the solar corona, which in this case is a word that means crown.

It has nothing to do with the past few years of insanity.

But the solar corona, it's this crown, it's this weird like hazy thing around the edges of the sun.

You can think of it as the atmosphere of the sun.

That's not quite right, but it's a good way to think about it.

It's a very diffuse layer on the outside of the sun that you normally don't see with the naked eye because it's too faint.

But once you block out that disc of the main sun, you can finally see it with your own eyes.

We actually discovered the corona scientifically through an eclipse.

They were observing an eclipse and they were like, "Hey, what's that weird shimmery thing around the sun?"

Now that corona changes over time.

Sometimes it's a little brighter, a little more dynamic than others.

And so with the naked eye in an eclipse, you can actually see it, and it shimmers, it stretches out well away from the sun.

And it looks like some sort of like science fiction movie effect, but it's happening in front of you with your own eyes.

With the moon blocking out the sun, it's so dark compared to everything else around it, compared to that corona, it almost looks like someone took like an ice cream scoop and just made a perfect scoop out of the sky and just cut a hole, a perfectly round hole in the sky.

And so that lasts for a few minutes, and your mind is just reeling from what you're seeing, and then suddenly it's gone and it just moves on and you wait for the next one is what you do.

You know, there are people who, once they experience their first eclipse, they spend the rest of their lives kind of chasing that feeling of seeing another eclipse with their own eyes.

It's like, it's just this whole... it's a thing that you can only experience personally.

Like I can't quite tell it to you.

I can just tell you to go do it.

Like you have to go do this.

So it is well worth anyone's time if you get a chance to travel to it.

I've encouraged my students to go ahead and skip.

Well, don't tell my fellow professors this.

I've encouraged them to go ahead and skip classes that day.

Like if there's not an exam, there's no reason to be in class.

Like, go, go to Ohio, go to Indiana, go to wherever you to go to see it.

- [Interviewer] Okay.

All right, well, maybe I have to pack up my kids and go.

You're selling me pretty good on this.

- [Aaron] Excellent, excellent.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep20 | 5m 23s | Scientists use eclipses for discovery and to prove their theories. (5m 23s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep20 | 5m 1s | CMU Professor, Dr. Ari Berk, describes how different cultures interpret eclipses. (5m 1s)

Eclipse Preparation with Scout Troop 366G

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep20 | 3m 59s | In Saginaw, Scout Troop 366G prepares to view the eclipse. (3m 59s)

Video has Closed Captions

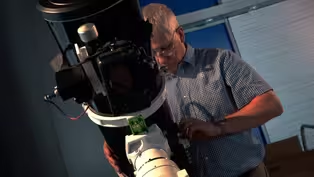

Clip: Ep20 | 3m 3s | CMU Professor, Dr. Axel Mellinger, shares his passion for astrophotography. (3m 3s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Special Programs is a local public television program presented by WCMU