Oregon Field Guide

Mounted Archery; Beaver Assisted Restoration; Trail Signs

Season 34 Episode 2 | 26m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Mounted Archery; Beaver Assisted Restoration; Trail Sign Maker.

Katie Stearns helps lead a new generation to take up the ancient martial art of shooting arrows from the backs of galloping horses; Revisit the 2009 Bridge Creek Project in eastern Oregon for an update on the success of the role beavers play in the landscape; Anyone who has hiked in a National Forest has seen one of the iconic trail signs crafted by Mount Adams Ranger Station volunteer, Dan Finn.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Oregon Field Guide is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Field Guide

Mounted Archery; Beaver Assisted Restoration; Trail Signs

Season 34 Episode 2 | 26m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Katie Stearns helps lead a new generation to take up the ancient martial art of shooting arrows from the backs of galloping horses; Revisit the 2009 Bridge Creek Project in eastern Oregon for an update on the success of the role beavers play in the landscape; Anyone who has hiked in a National Forest has seen one of the iconic trail signs crafted by Mount Adams Ranger Station volunteer, Dan Finn.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Oregon Field Guide

Oregon Field Guide is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMajor support for Oregon Field Guide is provided by... [ ♪♪♪ ] MAN: My rappel!

MAN: Oh, my gosh, it's beautiful.

MAN: Good morning, everybody.

Woo!

Let's do it again!

MAN: Nicely done!

MAN: Oh, yeah!

Fourteen and a half.

Yes, that was awesome!

[ people cheering ] There you go, up, up... ED JAHN: Next, on Oregon Field Guide: MAN: Fish party!

Whoo!

Fish party!

WOMAN: Oh, my gosh!

JAHN: In the early 2000s, researchers had a novel idea.

MAN: Yes, there they all are.

Enlist beaver to improve salmon habitat.

So, how did it all work out?

Then, meet the maker behind those lovely natural wood trail signs on your public lands.

But first, adventures on horseback.

We start our show with a story that brings an interesting twist to something we've all seen a lot of in the movies.

You know, the ones where you see legions of horseback-mounted riders armed with bows and arrows, engaged in fierce battle.

Well, here in the Northwest, producer Ian McCluskey joined a group of women who are mastering those same skills but for a very different reason.

WOMAN: Okay, here we go.

Come on, come on!

Yes!

Yes!

WOMAN: Yeah!

Beautiful!

When that arrow hits that target, it vibrates through my whole body.

It's just like, boom!

As soon as it leaves your bow, you know whether it's going to hit or not.

WOMAN: Yes!

Those first moments that you nail that bull's-eye, that's always one of those, you're like, "Yes!"

And then when you do it again and you get two in that bull's-eye, you're like, "Whoa!"

you know?

I don't know.

It's primal.

You can feel their hooves just thundering down the track, and your heart gets in a rhythm with them and your body gets in the rhythm with them, and when you're on, you are on.

[ women cheering ] Hitting things with a weapon on a moving horse, like, that's pretty awesome.

McCLUSKEY: Horse archery dates back to ancient times.

In Greek mythology, Sagittarius is depicted as the half-human, half-horse archer.

Across Asia, Europe, and North America, mounted archers gained reputations as formidable warriors.

WOMAN: It's an ancient form of archery.

I tell people, "That's how Genghis Khan captured the world, basically, is horse archery."

[ horse whinnies ] Although mounted archers are no longer used in warfare, this ancient martial art is being revived, practiced by a modern generation.

Hey, everybody!

Can you give me your name, your horse's name, your goal for the day, and how we can help you with that?

My name is Katie, and I am on Drogo.

My goal is to keep us in the track, but 120 points would be awesome.

[ all laugh ] I'm Elise on Buddha, and my goal is keeping him straight, forward, happy.

Hi, I'm Emily on Dakota.

My goal it keep my energy up, to keep my focus.

[ Emily shouts ] [ arrows whistle ] This weekend is an official competition for the World Federation of Equestrian Archery.

[ rooster crows ] Folks have come to the Flying Duchess Ranch in northern Washington from as far away as California, Montana, and Texas.

Oh, good girl.

Heading up the weekend's events is Katie Stearns.

She's invited the archers to her home.

Many of the horses are hers, which she has loaned to those without their own.

She started so many people in this sport, and so much of this community owes their love of this to Katie.

Instead of starting with one nocked, I'll start with one like that.

It's very quick to nock.

Horse archery is considered like the queen of the martial arts because there's such a feminine side to it.

You have to have the rhythm and the balance.

Good boy, Buddha.

I love you so much.

KATIE: It just takes harmony.

A-whoo!

[ clicking tongue ] KATIE: And you have to set your horse at the start of the course for the rhythm that you want.

And then you have to let go of the horse and then you have to contain that rhythm and then put that rhythm into your shooting.

When we get that flow, the horse is cantering and the rider is shooting.

It's usually that the rider has connected to the horse, and as the horse is rising, the archer is drawing.

And as the horse comes to the peak of their rise, the rider releases, because that's the smoothest, most stable spot.

When all four feet are off the ground, you have this moment of stillness.

She's one of those people that has that true talent, not only with the horses but with the archery and with people.

You know, my goal with this outfit was to show people that you can be a pretty princess and a warrior goddess.

[ laughs ] There's a lot of times that there's that emphasis on "pretty, pretty, pretty," and then there's like, "Oh, you're a tomboy, so you need to be like a tomboy."

You can be pretty and powerful.

[ women laughing, chattering ] [ all exclaim ] KATIE: Three, two, one, stop!

EMILY: Because Katie is such a supportive and nurturing person... Nicely done, folks!

...you get a lot of empowerment from her and she's empowering herself, and we're all like, "Yeah, we like that.

We want to be like that!"

So we want to empower and be strong and, you know, like, this is a very strong sport.

We do sometimes think about it as you are going to battle.

But sometimes through horse archery you find out that the battle isn't actually you and the target and the horse.

It can become this, like, ultra internal struggle.

And so many women have come to me with their stories and have told me how horse archery has helped them, and... it does so much for a lot of women who maybe were bullied, like myself, who was extremely bullied.

And Elise.

ELISE: In junior high, I got a little bit bullied and stuff, and so it just-- I kind of closed off.

But this just helped me kind of, like, open up.

Good boy.

You're building so much trust with these horses because you're not riding with reins.

Obviously, both of your hands are with the bow and the arrows.

And so there's a lot of that trust, and that translates not just to the horse as you're on the track but also with the people that are here to support you.

When I came into this, I had built up such a huge brick wall around me, because it was like, "I can't take anymore," you know?

"I don't-- I don't want any more pain emotionally."

And... [ exhales deeply ] you can't have that when you're on the horse.

And they-- They take it... and they release it.

And the archery, for me, is another aspect of that.

The horse brings it up and the arrow takes it away.

T3?

Four points.

Thank you!

The participants today are being scored and ranked.

Elise on Buddha: 73.27.

[ women cheering ] But although the athletes share a competitive spirit, they don't feel like they're competing against each other.

Emily on Dakota: 97.29.

[ exclaiming ] [ women cheering ] KATIE: Is that your personal best on this course?

Yes!

Of course there's a first, second, third, whatever.

But you're competing against yourself.

WOMAN 1: Whoo!

WOMAN 2: Yes, ma'am.

[ all cheering ] BEESH: If you stand by the judge's booth when people are going, everybody over there is like, "Yes, yes, yes!

Oh!"

You know, if it doesn't get in there.

KATIE: Oops.

Ooh!

Everybody is rooting for everybody else.

Part of the weekend's events are drills, the foundation of the incredibly complicated act of shooting arrows from the back of a galloping horse.

KATIE: All right, remember, shoot on the forward.

[ music playing ] [ all humming tune ] [ all exclaim ] [ all exclaim ] [ all exclaim ] [ Katie humming tune ] Oh, nice grouping!

I like that.

KATIE: Through all of the games that I set up, I want people to just play.

Just have a great time.

Just shoot and feel good about themselves and don't worry so much about the points.

Yeah!

Ha-ha!

[ all cheering ] So I try to do a lot of building our friendships through play, through games, and little competitive games, you know.

High five!

Good job, Beesh.

Archers, are you ready?

Ready!

And set!

Go!

[ woman cheers ] [ all shouting, laughing ] As I've been able to open up and let more of my personality come out, I've been able to connect better with my teammates as well.

Oh, yeah.

The competition will be done, but we don't go away.

We hang out around the fire, you know?

We have fun, we have random talk, sometimes we'll have music and dancing or whatever.

But we just have a good time.

[ music playing ] KATIE: Oh, my gosh.

Oh, I love you.

I love you, too.

We're happier people when we're out here on the track and doing what we love, and it translates to everything in life, right?

Are we having a cuddle puddle?

Ooh, cuddle puddle!

It's not just shooting arrows into a target off a horse.

It's about finding that peace in the moment... and in your mind, with all things coming together for that one moment in your life when maybe everything just feels right.

And then you can hold on to that little moment... [ chuckles ] and kind of face the rest of your life.

[ ♪♪♪ ] What do beaver have to do with salmon?

Well, this next story is interesting because in the early 2000s, I had a chance to join researchers in the Oregon High Desert as they put to the test this novel idea that they could use beaver instead of expensive equipment to restore degraded salmon habitat.

Well, our show's been around long enough now that producer Aaron Scott had a chance to retrace my footsteps over a decade later to see how it all worked out.

MAN: Shocking team ready?

AARON SCOTT: This is what it looks like when a bunch of biologists go fishing.

WOMAN: Oh!

Oh!

MAN: Fish on.

[ all laughing ] WOMAN: Wait, wait!

Oh, one.

Yeah!

There's our first steelhead of the day.

Number one.

But instead of pole, line, and hook... Oh, oh, get 'em all!

they have pole, electrical current, and net.

Oh, oh!

MAN: Hey-oh!

Fish party!

[ all laughing, exclaiming ] Fish party!

WOMAN 1: Oh, my gosh!

WOMAN 2: There's so many.

You might not be able to tell from their unbridled joy... Whew, that was a close one.

[ laughs ] but these biologists are counting fish during one of the worst droughts this part of Oregon has ever seen, fields baked and streams dried up or float so low and hot that fish die.

MAN: Oh!

Yes!

But in this one spot...

There they all are.

everything was different.

Bingo.

This is Bridge Creek, and it's full of fish today because scientists here established a now widely accepted idea: If we want to keep salmon and steelhead from going extinct, we should follow in the footsteps of nature's engineers: beavers.

MAN: There's some beaver tracks in the mud there.

It's rare here to see the beavers themselves, but there are signs of them everywhere.

Hey, beaver poop.

Who's hungry?

There is a pathway that these beavers take to migrate in between the two impoundments.

So you can see it's caked with mud here.

They'll just slide down it like this... [ woman laughing ] all the way, all the way down.

What makes beaver important to fish is not their poop or their pathways.

It's the dams and channels they build.

Downstream, we saw a little riffle that was two feet wide and maybe two inches deep.

And now we have almost an acre of water percolating through this landscape.

So the impacts that these ecosystem engineers can have to create a wetland is second to none, really.

Of course, one person's wetland is another person's flooded field, which is why beavers have long been seen as pests.

So to understand how scientists like Gus came to celebrate these rodents, we need to step back in time to the beginning of this groundbreaking project.

MAN: This is channel incision on steroids.

So this is a pretty extreme example.

NOAA biologist Chris Jordan met up with Oregon Field Guide in 2009.

He told us that valley floors across the West used to be full of beaver ponds and wetlands, but then European trappers killed most of the beavers and settlers drained the ponds and pushed all the water into simplified streams to make room for their crops and livestock, often with big consequences.

Because it is this really erodible landscape, the stream cut down.

So here, right on the edge of this incised channel, you've got bare soil.

You've got this cut edge and you've got erosion.

These streams are a huge problem in the eyes of fish biologists because they don't offer any habitat diversity.

That means salmon and steelhead have nowhere to shelter and survive through hot, dry summers or winter floods.

It's one reason their populations are falling.

Then, something caught Chris' eye.

Where beaver had returned and dammed up ponds, fish were doing better.

This is beaver country.

The populations are coming back.

There's a beaver dam right over here.

In 2005, there were 300 juvenile steelhead rearing in there in the summer.

That gave the NOAA team a novel idea.

Instead of using expensive bulldozers to restore these streams, maybe they could recruit beavers to do it.

I think we're just sort of trying to go back and say, "What if there were more beaver?

What if they had more stable populations?

What if they had more stable structures?

Would that affect what the stream looks like?"

And so those ideas are-- they're new.

The challenge was, creeks here often flood in the wintertime and wash away beaver dams.

So the team built a series of starter structures, what they called beaver dam analogs, or BDAs.

The idea was they'd work like a bunch of speed bumps to slow the stream and weaken its power so that beavers could then take over.

So the question was: did it work?

To find out, we went to meet Chris and Gus at the exact same spot over a decade later.

Take an old guy out in the woods.

Nailed it.

CHRIS: Oh, little gopher snake.

Rattlesnake mimic.

Hey, buddy.

The sites are just right downstream.

GUS: Looks like a-- Yeah, that's it.

GUS: There's this one here, too?

Yeah, so these are the ones looking downstream, and then that's wrapping around that bank.

Remember that BDA Chris and his team installed below the tree in 2009?

Well, beavers have completely covered it with their own dam.

I don't know, somewhere in here.

The willow have been here for quite a while now.

Turns out beavers did use the BDAs, and the result was an eight-fold increase in the number of dams in the study area.

All those dams slowed the water and backed up silt, which raised the incised creek bed.

Then the beavers dug canals and spread the water out onto the creek banks, creating a growing wetland that's now home to all sorts of plants and animals.

What they did was transformative in those treatment areas.

And now, beaver control the hydraulics.

The results are clear.

This is our footage of one of the treatment areas from 2009.

You can clearly see how much the stream spread out into a wetland by the time we returned in 2021, even in a late summer drought.

And now, instead of flushing water straight through, the area stores it and releases it over time, something even more vital in the face of drought and climate change.

But remember, the goal of this project wasn't just more beavers.

It was more fish.

Yeah, so should we tag the fish now?

GUS: Yeah.

WOMAN: Who's the big boy?

We insert these little PIT tags in each of the fish.

We use them so that way each fish has an individualized ID.

Ready?

Ready.

Then they contract the fishes' movement with antennas set up from Bridge Creek all the way out to the ocean.

14.6.

We can develop their life history and estimate abundance, and then we can also look at survival and production.

So years spent building BDAs and tracking the daily lives of fish.

What did they learn?

Well, the average number of juvenile fish in the study area increased by almost 180 percent.

And their seasonal survival rate increased by 50 percent.

These results fueled a seismic shift in how we think about beavers, from pests we should remove to partners we should recruit as we work to restore ecosystems and threaten fish populations.

The low-tech process developed here at Bridge Creek is now so widely accepted that the USDA will fund BDAs in agricultural land as part of its conservation strategy.

The whole community of us who started working here has grown to hundreds of projects.

And that's really cool, because this is the kind of work that has to happen over tens or hundreds of thousands of stream miles in order to get the benefits that we can see in Bridge Creek.

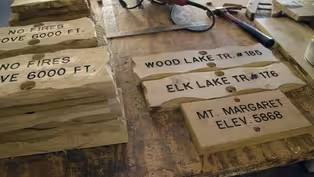

[ ♪♪♪ ] Anyone who's hiked in a national forest has seen signs just like this, the classic trail sign with the distinct handmade look.

I've always wondered who makes these?

MAN: I've been an outdoor person all my life, and I've done a lot of hiking.

While I was hiking over the years, I've noticed a lot of trail signs are missing or old and you couldn't read them anymore, and people I hiked with would often say, "You know, the Forest Service needs to put up some new trail signs."

And I found out it wasn't that easy with the Forest Service because they're pretty limited on their staff and they just don't have the money to buy signs.

So I offered my services to help make them.

Dan Finn is a volunteer for the Mt.

Adams Ranger District.

Several days a week, he comes to the woodworking shop at the ranger station to make trail signs.

I've never done a lot of woodworking.

I struggled a little bit with it at first, but in time, it came to me.

[ machine whirring ] Unfortunately, I had a mild stroke, but I was still able to make the signs.

[ saw whirring ] You can't always tell by looking at the piece of wood that it'll make a good sign.

The oak lasts quite a while.

Many signs today are carved with the aid of a computer.

Dan uses an old-fashioned router tool.

This is the router table.

It's an older piece of equipment and parts are kind of hard to find.

So we've got three different sizes we can make.

Some of the simple signs probably take a couple of hours, but some of the more extensive ones, it takes up to a day, maybe a day and a half.

Well, a little fuzzy, but I'll put that through the planer and it'll smooth it right up.

Dan makes two kinds of signs: the iconic brown signs with the yellow lettering and signs that are specific to designated wilderness areas.

Signs that we make for the designated wilderness, we usually have a kind of natural look, kind of scarfed on the edges and posts that we've made out of cedar.

That's what these are here.

In the old days, they would cut the signs out with an ax.

That's why the wilderness signs are kind of scarfed and cut along the edges, to make them look like they're hand-hewn.

If when I finish them, they don't look right, I'll take them back in and try to correct whatever I feel is wrong.

Over the past few years, Dan has made some 300 trail signs.

They can be seen across the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

A lot of these signs that I make, you can't tell how old they are.

I mean, you could put them up next to one that's been there for many, many years, and it looks the same.

You know, some people have said, you know, that they're just out there in the weather and hanging on a tree, what does that matter?

But I guess it matters to me.

I want to make sure it's right.

I'm hoping that the ones I make will be there for a long time.

The wilderness has given me a lot, and this is one small way I can give a little back.

[ ♪♪♪ ] You can now find many Oregon Field Guide stories and episodes online.

And to be part of the conversation about the outdoors and environment here in the Northwest, join us on Facebook.

[ birds chirping ] Major support for Oregon Field Guide is provided by... Additional support provided by... And the following... and the contributing members of OPB and viewers like you.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S34 Ep2 | 8m 29s | In eastern Oregon, scientists enlist the help of beavers in an effort to save salmon. (8m 29s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S34 Ep2 | 9m 51s | Katie Stearns leads a new generation in the ancient art of mounted horse archery. (9m 51s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S34 Ep2 | 4m 14s | Dan Finn crafts the iconic trail signs found throughout our national parks. (4m 14s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Oregon Field Guide is a local public television program presented by OPB