Mind Over Matter

Youth Mental Health Matters

2/29/2024 | 56mVideo has Closed Captions

The pressing concern of youth mental health comes to the forefront.

In northeastern and central Pennsylvania, the pressing concern of youth mental health comes to the forefront as "Mind Over Matter," a regional initiative, endeavors to illuminate the challenges faced by the younger generation. Through compelling narratives and informative discussions, the show aims to amplify awareness to address the mental health needs of the youth in these regions.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Mind Over Matter is a local public television program presented by WVIA

Mind Over Matter

Youth Mental Health Matters

2/29/2024 | 56mVideo has Closed Captions

In northeastern and central Pennsylvania, the pressing concern of youth mental health comes to the forefront as "Mind Over Matter," a regional initiative, endeavors to illuminate the challenges faced by the younger generation. Through compelling narratives and informative discussions, the show aims to amplify awareness to address the mental health needs of the youth in these regions.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Mind Over Matter

Mind Over Matter is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Announcer] WVIA presents "Mind Over Matter: Youth and Mental Health."

From the Central Susquehanna Intermediate Unit in Milton, here's Tracy Matisak.

- Hello, everyone, and thanks for joining us for this important conversation about our children and their mental health.

Last year, one out of every six kids in the United States ages 12 to 17 experienced a mental health disorder, one in six.

Here in Pennsylvania, 98,000 adolescents, ages 12 to 17, have depression.

Fewer than half of them receive treatment.

To make matters worse, kids who struggle with depression are more than two times as likely as their peers to drop out of school.

(intense dramatic music) Well, in a few minutes, we will meet some young people who have courageously shared their stories with us and how they're addressing the challenges they've been facing.

But first, a closer look at how some parts of Northeast and Central Pennsylvania came to have relatively high rates of youth mental health challenges, and what's being done to help individuals and families who are dealing with it.

For that, we turn to our expert panel.

Dr. Dr. Angelica Kloos provides psychiatric care to children and adolescents at the Geisinger Healthplex in State College, Pennsylvania.

She also serves as the division chief of outpatient psychiatry services at Geisinger.

Julie Petrin is the director of Behavioral Health Support Services here at the Central Susquehanna Intermediate Unit.

She has a background in special education, and her work focuses on building mental health systems and partnerships in local schools and communities.

Erin Demsher is the Behavioral Health Support Services Impact Grant Project coordinator here at the SCIU.

She's also a board certified behavior analyst, and her work involves creating systems, developing collaborations, and determining mental health needs within the school's communities.

And Kelly Feiler is president of the Regional Engagement Center in Selinsgrove, which focuses on youth mental health and wellness.

And she's been working with youth since 2006.

Welcome to all of you, and thank you so much for being with us.

I wanna ask a couple of questions before we get into some of our stories.

And Dr. Kloos, I'll begin with you.

Some of the studies say that in Lackawanna, Luzerne and Wayne Counties in particular, there are higher rates of depression and suicide attempts among young people than some of their peers in other parts of the state.

Can you talk about what some of the contributing factors to that might be?

Why we're seeing higher rates in certain parts of the state and not others?

- Sure, I would suspect that it has a lot to do with the environment around in these areas.

These are areas where there are not a lot of services, there's not a lot of access to care.

So being able to get in to see someone for help has been a challenge.

Even getting transportation can be a challenge if you even go back to basic needs.

Internet has been a challenge, internet to get services even outside of this area.

So I think there's a lot of factors that go into the community having more trouble, and I think the children are just a symptom of that.

They show that what we're seeing around them.

- Yeah, Erin, we mentioned earlier that fewer than half of the 98,000 kids in Pennsylvania who struggle with depression have received treatment, which speaks to, to Dr. Kloos's point, a lack of access being a big factor.

How can kids get help, and where does a parent begin when they have a child who's struggling?

- I think we're very fortunate that in our school systems, we do have connections.

So if parents are struggling, reach out to the school system, talk to their school coordinator, talk to the school counselor, find out what resources are available within the region.

If that is not available, look to the internet to see if you can find something online.

- Yeah, Julie, what should parents be looking for in terms of signs that their child might be struggling with anxiety, depression or some other mental illness?

- I would say changes in behavior, changes in appearance.

Definitely withdrawal and nervousness about events that are coming in transitions.

- Like an uncharacteristic kind of nervousness.

- Right, right.

- Yeah.

All warning signs for sure.

Kelly, a recent Pennsylvania youth survey indicated that 40% of the young people in Snyder County, which is where you work, feel sad or depressed most days.

It's 40%, 18% have considered suicide, 11% have made one or more attempts.

How does the Regional Engagement Center, where you work, help kids who are struggling with these kinds of issues?

- We have the benefit of location.

Our community center is, like, three blocks from the school district campus, so the kids are able to walk to our community center every day after school, and we have a free drop-in program from three to six every day.

And we have the luxury of providing that service to our community and to any student in grades three through six.

So we get them there in the afternoon, and that is our chance to implement grassroots things like, providing mental health check-ins with local therapists, having Transitions of PA provide Team U groups.

We have our REC leadership group that meets with Cheryl Stump and does trauma-informed yoga.

We do QPR, the question, persuade, refer, suicide prevention, training, seminars.

We encourage businesses to do the Youth Mental Health First Aid, so that the kids who come to us, we can say, go out and get jobs at those places.

- Great, well, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic really created a lot of mental health issues, not just for kids, but for adults as well.

And in fact, the pandemic led to a big increase in anxiety, really across the board, but also a notable increase in eating disorders, including in very young children.

Delaney Shipe was a happy-go-lucky preschooler until COVID lockdowns kept her from seeing her friends.

The anxiety that resulted led to an alarming weight loss.

Well, today Delaney is a healthy, happy third grader, thanks to her parents, a therapist and a school environment that addresses childhood anxiety head on.

(gentle ambient music) (birds chirping) - [Delaney] "Something is missing, you need Will," says, Callie.

- Callie.

- Callie.

- Callie, it's her name.

- Pete, Bob and Callie.

His go-kart is the fastest.

- First time I noticed signs of anxiety in Delaney was right after COVID.

When the whole world was shutting down, she was taken out of preschool, wasn't around her friends anymore, couldn't really see family or friends besides our immediate family.

And that's when we kind of noticed her becoming shut down, became sort of a show of herself, lost interest in all the things that she once enjoyed doing.

Prior to COVID, Delaney was just a very social butterfly.

She loved preschool, loved hanging out with her friends and her cousins, just was wanting to do things all the time.

♪ Happy Birthday to you - How great is that?

- It's very green.

(Delaney screams) (merry piano music) (people chattering) - Hey, do you know what lollipop this is?

If you get a cabbage lollipop, ew, ew, ew, ew, ew!

- So when COVID happened, and again, the whole world shut down, she was just... (melancholic piano music) - I was sad because during kindergarten I really loved seeing my friends.

- Her whole world was rocked.

So she kind of stopped all the social interactions that she once enjoyed and just kind of became very sad.

- Seeing Delaney change from a happy-go-lucky girl to an anxious girl affected me as a parent greatly.

I wanted to just bring that smile back to her.

I wanted to bring that light back in her eyes.

I was desperate to find anything to make her get that back.

One day I remember picking her up and she was just so light.

She just felt like a feather, you know?

And it's just like, I looked at her and she looked like a skeleton.

And that's hard.

That's hard to see your happy little girl turn into this light skeleton of herself.

- I was really scared to eat, because there were a lot of people that were sick during COVID.

- When we first started seeing signs of her losing weight and stopping to eat and crying that she was hungry when she wanted to eat and she couldn't eat, that kind of led us to knowing that we had to kind of really seek some professional help now.

It was more than just her being sad.

(pensive music) I was concerned we were gonna be getting feeding tube level because she would just not take anything at all.

So we reached out to the pediatrician, got her in right away with them.

They got her into counseling fairly quickly with a child counselor, and we also set up feeding therapy at the Hershey Clinic where she was getting feeding therapy as well to help with being able to combat her fears with food.

(hopeful music) - When I saw Delaney start to eat again in this feeding therapy, it was so cool.

I mean, it's like, you want your child to have to win trophies and, you know, get medals of honor, whatever, and go to Harvard, you know?

But like, just seeing her eat an apple was like a victory.

You know, it's hard not to cry thinking about it, but I'm just so proud of her for being able to take a bite of food, you know?

It was so cool.

Is it good?

- In light of all the challenges, I am really hopeful for Delaney's future.

She has made such amazing gains in her anxiety and her communication skills, talking about her feelings and her eating issues.

We really don't have any issues in terms of her feeding anymore.

She's been very open with her counselor and with us now about her feelings.

And I've also heard her talking to other kids that have been nervous, and it's nice to see her be able to provide them with some, you know, advice that has helped her.

- [Interviewer] What would you like to tell other kids who might be worried like you?

- It's gonna be all right.

Your parents are going to be okay.

I was scared when the COVID started too.

- You hear about mental health, you hear about anxiety and medications and all these things, but you don't really know about it until it is in your household.

Don't bury it, you know, address it with your child, talk to your child about it and just look for ways together to help.

- I think that's the easiest one.

- Oh, now you say that, sure.

Look at that.

- [Tiara] Awareness for childhood anxiety, I feel, could definitely be improved in our community.

I do think that since COVID has occurred, the amount of mental health crisis that has occurred has just skyrocketed.

I think that it's good to have schools be on top of it as well.

Delaney is in like a worry group at school, so having it be at home, but also at school is really helpful as well to kind of help bridge that gap in community and at home.

- It's stuck.

- It's stuck.

You wanna skip it?

(light buzzing) - No.

- Okay.

You're gonna work at it?

- So I would say my ending to the journey is just to advocate for your child, do what they need.

And if it's more than what you can provide, that's okay.

So just, you know, keep fighting for your child, keep, you know, reaching out and opening up to your children about your concerns and your anxieties as well, to help know that it's normal, and it's something that we all go through.

And it's something that we have to be able to process as we continue to grow.

(pensive music ends) - Well, special thanks to Delaney and her parents for sharing their story with us.

And also thanks once again to the Central Susquehanna Intermediate Unit for hosting us for this episode of "Mind Over Matter."

Let me turn now to our panel, and Julie, I'll begin with you, because clearly, the pandemic sparked anxiety in so many of us.

But a story like Delaney's really brings home its effect on young children in particular, especially in those early days and weeks and months of COVID.

Can you talk about how an event like that can serve to undermine a child's sense of security?

- Sure, so I think about the kids who were home and not interacting with peers, and if you think about child development, kids learn through playing with other kids.

They learn how to regulate behaviors and emotions.

And many kids didn't have that experience.

- Yeah.

- So that whole sense of themselves wasn't there.

They didn't develop in that way.

- Yeah.

- And I think of Delaney then.

So she was in school, and then there was a halt to what was happening at school.

So those worries, like, what's going to happen?

Nobody knew it was going to happen.

- Yeah, it's something where even the adults in her life wouldn't have had answers at that point, because it was just unprecedented.

- Right, so I think the unpredictability and that not being sure of what was next had a big effect.

- Yeah.

Dr. Kloos, Delaney said that she was scared to eat, and I'm quoting because a lot of people were getting sick during COVID.

Can you explain how an event like COVID-19 can, how the pandemic itself can lead to eating disorders, particularly in young children?

And I thought that was such an interesting statement that she made.

- I don't know Delaney, but I suspect that as we were all trying to figure out why this is happening, why this is occurring, how can we protect ourselves?

People are dying.

We don't know if it's gonna be someone in our house or family or our loved ones.

And so thinking about things coming in from the outside, we were all very bunkered in, protected in.

And to think about things coming in the outside, food comes from the outside, and so is that safe?

And so my bet is that when we think about bringing things in that could be contaminated, it must have been really hard for her to even think about eating it, because we don't have control over that.

- Yeah.

- And when we don't have control over it, bad things can happen, especially when the anxieties are high.

- Yeah, and also, what about just beyond being afraid of things coming in from the outside and being contaminated?

Just the sheer anxiety of not knowing what's coming, where we're going, I imagine that in itself can be a factor with an eating disorder.

- Mm-hmm, right.

So with eating disorders, there's a lot about being able to get a sense of internal control.

And in a situation where we really don't have any control on the outside of our lives, there's a desire to control something.

And so I could see why that would link to eating disorders.

- Yeah, Erin, you have worked with Delaney, and her parents were able to get her into feeding therapy, they mentioned.

What does that involve?

- So feeding therapy was at Hershey, Penn State.

And Delaney went down there, and they slowly introduced foods for her.

They introduced preferred foods and foods that she had eaten previously, and then new foods, and slowly used reinforcement consistency, but then also teaching the parents, so the consistency could happen at home when they weren't at Hershey.

So it was using small incremental steps to get her to be feeling safe to eat those foods that she loved before.

- Yeah, how long does it take to do that?

I mean, to really get a child from the point where they're afraid to eat anything, to the point where they're eating reasonably well again.

- And luckily at Penn State, she felt safe there.

So she was able to eat some foods there, but then coming home into a different environment is another thing.

So building that consistency up, it could take a long time.

And it's a lot of following through with it and using that reinforcement, ensuring that she is safe eating those different foods.

- Yeah, Kelly, we have been hearing for a long time about the shortage of therapists and other mental health professionals, particularly since COVID, because the need has become so great.

What do you suggest for parents who are trying to get help for their kids, parents like Delaney, who ultimately were successful, but it can be difficult for parents to find the resources, given that there has been such a shortage of mental health professionals.

What do they do in the meantime?

- That's a very good question, and we talk about that a lot as we talk about the initiatives that we wanna do at the REC, because we see, you know, families worrying about insurance.

They're worrying about finances, they're worried about stigma.

And so, you know, we often have the parents come and talk to us, or we talk to them about what's going on with kids at the REC.

We have to say, you know, do the 211, you know, go ahead and, you know, go to the Susquehanna Valley United Way, go to the Central Susquehanna, you know, Intermediate Unit.

There are resources, but we have to give them that little push, you know, make the connection for them sometimes, you know, want me to make that call for you, and just sort of, like, push the envelope in terms of the resources we can make available.

- Yeah, Erin, Delaney's parents mentioned that she's part of a worry group at school.

Can you explain what a worry group is and how it works?

- Yes.

So we're really thankful that a lot of schools are starting to use tier 2 interventions and providing that support to students within the school system.

Students are in school for a really long time, and we wanna have that resource available for them.

So the group that Delaney participates in uses her school counselor and peers within our school, and they're building that relationship.

They're realizing that they're able to talk to each other, they're allowed to share their emotions, and then those people are always there for her as she moves forward in her journey.

- I feel like we all could use a worry group, (chuckles) not just for young kids, right?

- Right.

- I think that would be a good thing for grownups as well.

Well, roughly 7 million Americans struggle with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Four years ago, Colby Hughes became one of them.

In light of the diagnosis, her intrusive thoughts and irrational fears began to make sense.

And for Colby, living with OCD has been a journey, but one in which she's not alone.

With the support of others, including her therapist, she's making progress.

She shared her story with us to help others understand what OCD is and to encourage acceptance and support for those who are on a similar path.

(traffic whooshing) (acoustic guitar music) - When I was first diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder, I felt more relaxed than I probably should have been.

It was nice to put a name to what was bothering me and not feel so alone, just thinking that I was the only one who felt like this.

(pensive music) (Colby screams) (Hughes speaks indistinctly) (camera shutter clicks) (pensive music) Looking back, when I was trying to figure out what was happening with me, I thought that it was just this very severe case of, like anxiety, or I honestly did think I was losing my mind a little bit, like, schizophrenia or something, like, a very paranoid person.

But once I had a name for it, it was easier for me to, like, put a name to the symptoms that I was having and talk to my therapist about it, and we could move from there.

(gentle pensive music) The symptoms that I have with OCD include intrusive thoughts, checking and counting, and just very, very debilitating thoughts where, you know, like, I have to actually seek outside help for myself to deal with them.

(melancholic piano music) (door latch clicks) (door squeaking) One of my fears with obsessive-compulsive disorder usually occurs when I'm driving in the car.

It doesn't matter if it's daytime or nighttime, I just always think that the person behind me driving their car is following me, and that they're going to follow me home, and then going to get out of their car and then get me in their car.

(chuckles) So, a kidnapping scenario.

I just am always concerned that I'm being followed.

That's one of my big fears with the obsessive-compulsive disorder.

(car door thuds) (quirky violin music) It's very difficult to manage my OCD when I'm driving, because I have to focus on driving first and then also focus on calming myself down, which does not work a lot of the time when I'm driving.

I usually have the radio all the way up.

♪ All you can do to feel today - That is until someone freaks me out who's behind me, and then I have to turn it down, (chuckles) and then drive to the police station.

(gentle piano music) I think something that definitely helped me was to write down what I was feeling.

Writing can definitely help me keep track of how I'm feeling or if I managed to overcome an intrusive thought.

And then looking back, you can look through and see what worked, what didn't work, what triggered at that time, if something was able to help, if something wasn't able to help and made it worse.

It can also help me keep track of what I wanna tell my therapist, because we tend to go over a week between appointments.

(pensive music) I think a point of balance in acceptance and having OCD is a very long journey.

(chuckles) And I've basically just started it.

You know, I've only had the diagnosis for coming up on four years.

I think there are some times where I can't combat the feelings inside of my head, so I am a little worried for myself in the future.

But as of right now, you know, can't borrow nerves from the future, so.

So because of the OCD, checking the doors and checking the lock on the door to make sure it is locked is one of the things that helps me realize that someone can't break into my house, even if they did try.

And it definitely helps me sleep better at night.

Like, I'll have to sneak down when everyone else is asleep just to make sure the doors are shut so that I can fall asleep.

Because it's not that I don't trust my family members, it's just, like, someone might have forgotten to lock it, and I just have to check just to be sure.

(ambient pensive music) Based on my own personal experience, I would like to convey that it's very scary living with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Your mind just never stops.

And I would like for other people to get the facts right about what it is, and make other people feel comfortable with someone who has it, not freak out themselves.

I'm in the very beginning stages of realizing, okay, it's okay for something to be wrong, but it's not okay to let it continue to be wrong and letting it continue to hurt you.

You need to kind of find ways to control it.

Yeah, I think I'm still very much working towards that.

(gentle pensive music ends) - Well, we wanna thank Colby for sharing her journey with us.

And we also wanna remind you that if you've had these kinds of struggles, please know that you're not alone.

If you need somebody to talk to or you'd like to explore some treatment options, dial 211 to speak with a caring person who can help.

Back to our panel, and Dr. Kloos, I am going to zero in on you for many of these questions, because I know that you have expertise in this area.

Colby said that she thought initially that her symptoms were a severe form of anxiety.

Was she right, is OCD a form of anxiety, related to anxiety?

- So it's interesting, we used to include OCD in our anxiety disorders, now giving it its own separate category in our diagnostic manual.

But it is very distressing in the way that anxiety is distressing.

And so there are a lot of overlapping features, yes.

- Yeah, in Colby's case, the OCD manifests itself as intrusive thoughts that ultimately seemed to have to do with safety.

She described having fears that the person behind her was following her and was coming after her, thoughts about the house being broken into.

What are some of the other ways that OCD manifests itself and doesn't boil down ultimately to a perceived lack of safety?

- So safety is just one of the intrusive thoughts that you can have with obsessive compulsive disorder.

And they tend to be different varieties.

Safety is a common one.

So the intrusive thought she's having is that things are not safe.

And then the compulsion that she has, that has to go along with it is the checking, going to the police station, checking her doors.

And it's those rituals that other people often notice first, because the thoughts for her are very internal, but the external behaviors, her checking the doors, her going back downstairs at night, those are the things that we look for in order to be able to identify.

So there's many, many different ways that this can manifest.

Another one is cleanliness and contamination.

So frequent washing could be one.

Those are the more common ones, but intrusive thoughts don't have to be like that.

So intrusive thoughts could also be anything that's really distressing, not a thought that you want.

So sometimes it's getting a certain word or song stuck in your head.

It could be as different as that.

And sometimes they're really distressing, because they're things that these children really don't wanna think about.

They can be violent, things like that.

And to be able to talk about those, knowing that it's not a thought they wanna have can be really difficult.

So I think it's really important to look for those behaviors.

So if someone's having a thought that they know they shouldn't be having or they don't wanna be having, it could be like excessive forgiveness, asking for forgiveness, excessive prayer, trying to get reassurance.

So you can look for those sorts of things in children too.

- Yeah, Kelly, Colby mentioned her relief at getting a diagnosis, that suddenly things began to kind of make sense for her.

I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about that, about just being able to put a name to something.

- That really struck home to me when I saw the video.

And I get that sense from a lot of the kids with whom we deal also is, something's wrong with me, what's wrong with me?

And to be able to talk about that with someone, to actually get as far as to get a diagnosis is, you know, wonderful.

But to be able to start talking about those kinds of things, sharing that information, and then it aids with the destigmatizing too, is getting a words out there that accurately describe what's going on.

Recently I just, you know, realized, you know, what a microaggression it can be to say, you know, I'm a little OCD.

When you don't have that diagnosis, you know, that kind of makes light of people who really do have it, you know?

- Yeah, it can land the wrong way.

- Yeah, yeah.

- Right, with someone who is struggling with something like that.

Erin, Colby mentioned that she does see a therapist and that she takes her notes that are helpful for that.

What are some of the ways that therapy can help someone with OCD?

- I think you have to find what is gonna be beneficial for you?

So for her, journaling and seeing her therapist is something that's really helpful.

Being able to express her thoughts, share her opinions, but then also be validated about what she's feeling and that it's okay to feel that way, and having someone walk you through how to solve that and how to work through those thoughts.

- Would cognitive therapy be one of the modalities that?

- Yeah.

It definitely could be.

- Yeah.

- And I think you have to find what works for you.

So for her, journaling might work, but for someone else it might be going for a walk or talking to a peer, or having a companion, those types of things.

It depends on the person and what you can try.

- Dr. Kloos, what about medication?

What are the treatment options for OCD?

- So the medication options for OCD are typically antidepressant medications.

And we actually, in the field of child psychiatry, we really don't have a lot of well-researched FDA approved medications.

And in OCD, we really do.

So I think there's a lot of good treatment options that you can use.

And most studies are gonna show you that using therapy plus the medications together will get you the most effective response for OCD.

- Yeah, Julie, what advice would you have?

And I know that you work on putting systems together and partnerships, but for a parent who might be concerned that their child is struggling with something like this, what advice would you give them?

- I would say if the child is coming to the parent, they probably played it over a lot in their heads, maybe even talk to their friends.

So I think for the parent to take it really seriously in that moment, and then for the parent to act, call the family doctor, call the school as one of the people here said earlier.

Be relentless to find the help that you need.

- Yeah, Dr. Kloos, one of the graphics in that piece talked about the importance of early intervention.

So I guess the question would be, if it's not treated early, can it worsen over time?

And can OCD change over time in terms of the symptoms?

- Yeah, so I think that when you think about OCD, you wind up in patterns of behavior.

So the more that we get ingrained into a pattern, the harder it is to break.

And what we notice is that not just the person effective of the OCD, but also the family begins to accommodate for those symptoms.

So for an example, if it's having a certain order in your kitchen cabinet, and everyone knows that you can't mess with the order, because that person will get upset, everyone just make sure that we keep things calm so that we don't upset the person with OCD, before they maybe even know that it's OCD.

So the more that these rituals and behaviors get ingrained, they become culturized, and it's really hard to break.

So yes, I think getting the early intervention and catching it early is very helpful.

Does it mean that you'll never have OCD symptoms again in your life?

No, I don't think so.

I think that we usually see manifestations of any kind of really behavioral health disorder when stresses are high, when there's a lot of concerns going on around, when we don't have all the strength and support we need.

And it could come out in different ways.

That's absolutely true.

So if you have an obsession or compulsion one way, later on in life, it could come out another way.

- Can OCD be cured or is it something that has to be managed over the course of a lifetime?

- I think it really depends on each person.

So I think that there are small children that I see who have a short bout, we treat it, and I don't really know that they wind up with any kind of concerns later on in life.

I think it really depends on the course of their lifetime.

I think it makes 'em more susceptible during stress to have those symptoms come back out again.

So it doesn't mean that someone is gonna be suffering with symptoms every day for the rest of their life, but it means that there might be pockets of time throughout their life where they really have to focus on it.

- Yeah, and finally, are there risk factors for OCD genetics, anything like that?

- So they have seen that family histories are important when looking at OCD, because people that have OCD or anxiety disorders are more likely to have children with OCD.

It doesn't mean that anyone with OCD or an anxiety disorder is gonna produce a child with OCD, but it is something we look at.

And it's also true that smaller children before puberty, it's more common in males than females.

- Okay, well, we are talking about a variety of mental health issues that young people are struggling with.

And of course, suicide is one of the leading causes of death among American adolescents.

After two Danville High School students died by suicide within months of each other, their classmates decided something had to be done to prevent future tragedies.

That was the beginning of Danville SPM, Students Preserving Mental Health.

Three years in, they are stamping out the stigma around mental health by raising awareness, sharing their own struggles, and providing life-saving resources to their classmates.

(ambient pensive music) - Suicide is the second leading cause of death among children, ages 10 to 14.

One in six people, ages 10 to 17, will experience a mental health disorder in their lifetime.

Half of all mental illnesses begin by the age of 14.

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide.

(gentle ambient music) Danville SPM is a student organization run club that was formed three years ago after two students from Danville High School lost their lives to suicide.

- We're a very rural area, and our school is relatively small.

Nothing like this had ever happened.

Something needed to change.

This group was put together to take action and put awareness into the community about mental health.

- I personally knew the first one pretty well.

I played sports with him.

For me, it was a shocking experience.

I was in a lot of disbelief since I was only in sixth grade.

- It affected our entire town.

All of the teachers knew these kids.

We knew their families.

- Each time it happened, I was like, something is not right.

Like, people aren't doing enough.

Because if people were doing enough, then this wouldn't be happening.

- The activism behind the whole mission is incredibly important for people to know that they're valid and it's okay not to be okay, we're here for you.

- But since our club has grown, we've been trying to educate our community.

We've been trying to get our community involved with our mission.

- We started putting ourselves out there, like, we're here for you, and putting messages around the school so that that won't happen again.

- I mean, our acronym is Students Preserving Mental Health.

But I think it goes beyond what the name of our club is.

I think that we promote a lot of messages to the community and not just the school, because it is such a stigmatized thing.

- There's a lot of people who struggle out there and they don't know where to go to.

So we're just a quick guide for them.

If they need help, they can come to one of us or we can get help for them.

- It was huge.

There was probably, what do you say, like 5,000 people there.

There was a lot of people there.

So I'm hoping we can make it bigger and better this year.

- What about like a halftime, like, basketball games?

The boys basketball games.

The kids come out and pay a dollar.

Do, like, half court shot.

- We can do that.

- That's what it is.

A dollar?

- Yeah.

- She's awesome.

She does a big job in this club that we have.

She helps a lot.

And like, most of the time that she puts in it, it's awesome.

- I decided to take this on, not only because I'm passionate about mental health, but because I'm a mom.

I'm proud of the kids.

Yes, they've raised a lot of money and they volunteer their time, but they're sharing their feelings with the community, which is sometimes really hard to do.

- I struggle with stuff myself, and I kind of wanna put it out there.

Like, I do understand, I can relate to you.

- Because they're being vulnerable, I truly believe they're saving lives.

- Suicides would decline if we would be more open to talking about things, knowing that adults and parents are there to, like, comfort us and not just judge us.

- The times have changed.

Kids are dealing with things now that we never dealt with when I was a child.

- I think social media plays a huge part in mental health.

- Social media just put such a false image on what the world actually is, because many, many are struggling, but they don't wanna show that.

Because you can hide behind social media and you can change things to however you want them to look.

- Or there's also cyber bullying that goes on.

And you can just hide behind your phone and no one will know it's you.

And you could just put things out on the internet saying bad things about people and nothing will be done about it.

- COVID, I saw firsthand what COVID did to our students, and it's just really had a huge impact on them.

- I hope that in the future, people feel comfortable enough to reach out to, like, any of us.

- Anyone can dial 988.

You can call or text that line 24 hours a day.

- It doesn't make you a weaker person.

If you ask for help, it makes you a stronger person.

- You're not alone.

You are relevant and you are loved.

- Well, we certainly want to thank Megan and the students of Danville SPM for sharing their work with us.

And we also wanna thank once again, the Central Susquehanna Intermediate Unit for hosting us for this episode of "Mind Over Matter."

So much to talk about here.

And Julie, I will begin with you, because those two student suicides at Danville High School really shook not only the school, but the surrounding community to its core.

But this community went beyond grieving.

They decided to take action.

Can you talk about just the power of community taking a stand together and what that can do to prevent future tragedies?

- I think of the awareness that this club brought to the Danville community that maybe wasn't there before.

And I think about all of the other school districts that our intermediate unit serves and how powerful it could be if every school had a club like this.

We recently hired two high school mental health student interns, Ruth and Eli.

So I just have to put that out there.

And they are helping us create a youth advisory panel made up of students across all the districts in our intermediate unit.

So we can start to do the work, like the Danville SPM Club.

- Yeah, Kelly, it's one thing for adults to be involved, and certainly they need to be, but can you talk about the power of peers especially, because these young folks are really working to help each other out with this and to look out for their classmates.

Can you talk about the power of peer pressure in a positive way?

- Yeah, I remember hearing about that Danville group right as soon as they started, and just, you know, wanting to take that inspiration and bring it to the kids, you know, that'd come to our community center and the Selinsgrove Area School District, and give them chances to talk, talk to each other, talk to professionals.

You know, we brought in, for last school year, we had a licensed therapist there every day of the week just to come and, you know, be able to hang out and talk with the kids that were hanging out there.

There's a group at Susquehanna University's campus called P.S.

I Love You, which is a national organization, you know, set up to prevent suicide.

And they are planning a family fun night at the REC, and the kids love to attend things like that.

Just knowing that there are places that they can go and be together and talk about it.

And that there are, you know, people in the community, they're willing to make those opportunities available for them.

- Yeah, Erin, when you hear about two students within months of each other dying by suicide, of course, that raises the fear of copycat events.

What can adults do?

I mean, and certainly we saw it with Danville where everybody decided to pull together.

But can you talk about the importance of when you start seeing something like that, taking those steps to just sort of shore up the mental health of students who might be thinking that way?

- I think the biggest thing is you have to have the conversation.

You can't be scared to have the conversation.

If you think back to question, persuade, refer, which is the QPR training, they want you to ask the question, are you struggling?

Is something wrong?

Like, be direct with that individual or your child and have those conversations.

You could save their life by asking that question.

- Yeah.

- So we wanna have a open conversation, and sometimes it's really hard.

It's really hard and it can be very vulnerable.

But we want people to feel comfortable and connect with different resources within the community if you don't feel comfortable going to Geisinger, going to the REC Center United Way or different resources to have those safe conversations, or how to have those conversations with your students or your children.

- Speaking of Kelly, this is something that you and I talked about earlier, that whole questioning process.

What does that look like typically?

Or what are the kinds of questions?

- Well, QPR is question, persuade, refer.

And it's just asking the simple questions like, are you okay?

Have you thought about hurting yourself lately?

Or do you ever feel like, you know, you'd be better or you know, we'd be better off without you around, knowing that evidence says that asking those questions isn't gonna push someone over the edge to actually consider suicide.

And then having that person hear that question and realize that they're being seen, they're being heard.

And then, you know, if that person who's engaging in that conversation, once again, that's the power of the peers.

You know, we've trained, we've done several QPR trainings in the community for lots of school districts.

We've done it for adults in the community.

We're doing it for the Selinsgrove Area Rotary Club coming up.

And we've done it for third through fifth graders at our summer camp.

- Yeah.

- You know, so that they are equipped with the tools to ask those questions, 'cause they don't have to be hard ones.

They don't have to be really clinical.

Just, I'm here with you, are you okay?

And if you're not, I'm not gonna leave your side until we get you some help.

- Yeah, Dr. Kloos, to Kelly's point about asking the direct questions without concern that this is going to plant an idea.

I think that for some people there would be some fear that if I just flat out ask, am I planting an idea?

Can you speak to that and why it's okay to go ahead and ask the question?

- Yeah, I think it is a hard question to ask.

It's a hard thing to even ask in my office when I know that maybe I was the first one that ever asked a child that question in front of their parent.

And to have the parent just recoil back and just be worried about what that means, because it might be that we feel like their children have never heard about suicide or thought about suicide.

And by asking it, that we're suddenly gonna plant an idea that it is something that they may have thought about in a periphery, not maybe about themselves.

They've talked about it, they've seen it.

They've seen videos, they've seen TV shows.

It's there and it's in their life.

And if we don't ask them about it, then it's not okay for them to talk about it.

So I think that's why it's important.

- Erin, we've been talking about high schoolers in this case, but we know that even among very young children, there are those who struggle with suicidal thoughts, who might go ahead with something like that.

Can you speak to what happens to a very young child that they would even consider something like that, and why that is such a concern at this point?

- I think life is very fast paced.

A lot is happening.

There's sports, there is the stigma that you should be participating in all the sports, being straight A's, going to school every day.

There's a lot that a student is having to experience in their life.

So they have a lot going on, and we need to make sure that we're giving them the outlets that they need to communicate their thoughts, but then also feel comfortable what's happening around them.

- And Julie, I think that's an important point about the pressure that young people feel.

I, you know, see young people now, and I think about when I was coming up.

And we had our activities, but they weren't done at the level that they're done now.

Can you speak a little bit more to that and to just some of the pressures that young people, whether they're in grade school or they're in high school or college are facing?

- Sure, I think our youth are on 24 hours a day.

They're on at school in their afterschool activities, and then they're on with their social media, and it never turns off.

So to not be able to turn that off and just be at peace and in the moment, I think it takes a toll.

- Yeah, Erin, one of the students mentioned social media as a significant factor in the sort of mental anguish that can lead to suicide.

And he mentioned cyber bullying in particular.

The CDC says that nearly 15% of adolescents have been victimized by it and over 13% have made a serious suicide attempt.

Can you talk about that connection between online bullying and adolescent suicide, and what can be done to address that particular thing?

Because social media is in a class by itself.

- Yeah, and social media is hard because unless parents are checking their child's phone, they might not know what is happening.

So making sure that you have the programs on your child's phone, having open communication, who are you talking to, what websites you're on, you wanna make sure that you know what your child is being exposed to.

Because if they're being exposed to something and you're not sure, like, the suicidal thoughts could be happening because someone could be saying something negative about them.

They could be wanting to stay up or be up to what everyone else is doing online.

And they might not be able to feel comfortable, might not be able to have the perfect hair, the perfect nails that everyone else is showing on social media.

And those thoughts could be coming up in their heads.

So having those open communications, but then also having conversations about what they are using on social media is really important.

- Yeah, Kelly, signs that a parent ought to look for that might be concerning, that a child is thinking in that direction, - Withdrawal, a lot of dependence on your social media.

You're kind of going down a rabbit hole when you're really, really into that.

You know, their grades slipping, not wanting to participate in anything.

One of the, you know, the strongest protective factors against the, you know, the risk factors that the PAYS data shows are being involved in a pro-social or positive social opportunity and getting rewards for it.

So, you know, if they're not getting out there, and it doesn't have to be rewards for sports or anything like that, just like, yeah, you showed up today at, you know, the afterschool.

- Acknowledging.

- Yeah, yeah, I see you.

If they're not getting any of that.

- Yeah.

- Ask for help, yeah.

- Yeah.

- And parents need to know it's not embarrassing to ask for help.

That's a real hard one, and with the social media too.

- And it speaks to vulnerability, which the students talked about and how important that is in sharing their own experiences, being open, being vulnerable, and that that can encourage their classmates as well.

Well, of course, it's not just high schoolers and grade schoolers who struggle with their mental health.

Researchers at Boston University say that between 2013 and 2021, depression among college students increased 135%, anxiety increased 110%.

Well, we asked some students at Marywood University how they balance their mental health needs with the pressures of college life.

- [Reporter] As the new semester begins at Marywood University, some students may feel anxious.

I've talked to some students about how they deal with anxiety.

- Cope with a lot of it by de-stressing a lot and focusing on the positive.

I use musical a lot as a chair, if you will, to decompress.

- Yeah, I step away from whatever's causing me anxiety for even just a brief moment.

- Usually I just take, you know, if I got a bunch of assignments and stuff, I'll take, you know, one thing at a time.

You know, plan it out, you know, with a planner, write everything down.

- I say I deal with them by just taking it one day at a time, one thing at a time, living in the present moment.

I also try to take some downtime where it's just watching some TV, watching, like, a sports game, or just laying in bed and just relaxing and just decompressing.

- Well, we wanna remind you that if you have had these kinds of struggles, please know that you're not alone.

If you need someone to talk to or you'd like to explore treatment options, dial 211 to speak with a caring person who can help.

Really interesting to hear how students are dealing with their own pressures and stresses.

Dr. Kloos more than once I heard one day at a time.

(chuckles) Seems to be a theme.

- Yeah, that stuck out to me too.

And I think it is a really important coping strategy, especially in college, because if you think about it, they get these large groups of assignments and then they're kind of set to go, and you have to do it on your own time.

And a lot of those students are not ready to do that.

And so it gets left to the last minute, deadlines are coming, and sometimes kids are feeling helpless that there's no way they can do it.

And so, breaking it up into the smaller pieces, spreading it out, it's a skill that you really have to be able to learn, because not only is it gonna help you academically, but really it's gonna help you with your peace of mind.

- Well, and that brings me to a point that one of the students made about kind of having a planner and making lists of things and thinking through what's coming up, Kelly, and how important that is.

- And who teaches kids to do that?

Do they learn that in school?

Yeah, planning things out, which I think the, you know, I pride our director on teaching our REC leadership club that.

You know, they plan the teen nights.

You know, they have to backtrack.

You know, if we're gonna have a party on this night, you gotta actually back up and, you know, what kind of supplies do we need?

Having a break from it all is the concerning part, because they are on 24/7, the kids.

And so if anything, you know, yep, we do play loud music at the REC, and we encourage 'em to dance.

We encourage 'em to be silly.

We encourage 'em to turn off those phones.

Or if they have something distressing they've received, show it to us.

Get some, a reality check.

Is this normal?

Is this, you know?

And then we do the one day at a time.

All right, your best friend said this to you today, your best friend.

Let's see what happens tomorrow.

- Yeah, Erin, can you talk about other coping strategies that you can recommend, be it for younger children or for college students, or adults for that matter?

Because the fact is, so many of us struggle with anxiety in various forms, other mental health issues.

What are some kind of tried and true coping mechanisms?

- I think you have to find the coping strategy that works for you.

It might work for a couple of weeks, couple months, and then you might have to find something else again, 'cause it might not always be the best thing for you.

But I think one thing that we've been hearing a lot about is meditation.

It's just sitting there and being in the moment.

It's really hard to sit in silence, not have anything going on around you, sit in silence and just be present.

And that's sometimes really difficult to do.

But having the skills, learning it, using different apps that are available for that, I think, is really beneficial.

- Yes, and there are apps for that, just like everything else.

- Yes.

- Lots of meditation and mindfulness apps.

- Yes.

- And Julie, you know, deep breathing, right, is the thing that I keep coming across, because I read a lot about this stuff myself, and just the power of taking a breath.

- Sure, I mean, I think of my own kids who also struggle with being in the moment and being present.

And my daughter tells me when she gets out of bed in the morning and puts her feet on the floor, she just stops for maybe a minute and just breathes and processes.

Doesn't think about what happened yesterday or what's coming in the future.

- Yeah.

- I'm just to set her day up that way.

- Yeah.

And Kelly, Colby had mentioned in an earlier story about journaling and how helpful that's been for her.

Can you talk about why that seems to work, at least for some people?

- I think making yourself take the time to write it out, it's even different than like journaling online, because you know, you're just doing everything online anymore.

So taking the time to actually write things out makes you process it, and it gives you time to go back and reflect.

Like, have I thought this in the past, or you know, is there a pattern to my thinking here?

Or what was happening in life, you know, before I all of a sudden had that big blow up.

You know, how can I avoid those situations again, but just getting it out, getting it out.

- Yeah.

- Is so palatable.

- And Erin, having peers, having adults in your life that you can trust.

- I think peers go to peers more than they go to adults.

So making sure that the peers within our community feel comfortable having those conversations with their friends, with someone that might be an acquaintance.

Like, what can we do within the community to make sure that these peers have the resources, know to call the 211, know to call The Trevor Project, know to call 988, who are they reaching out to?

And I think that's something through the CSIU and the AWARE grant that we have, that we wanna provide those resources for the community.

- Yeah, the resources are there.

It's a question of seeking them out.

- Correct.

- Yeah.

Before we go very quickly, Dr. Kloos, any closing thoughts that you'd like to leave us with as it relates to youth mental health?

What would you like us to take from this conversation?

- You know, as I sit and listen to everybody, I think about one of the biggest risk factors to children thinking about suicide and its isolation.

And hearing about all these wonderful community resources to me, makes me think, okay, these kids aren't gonna feel as isolated.

They're gonna have a place to go.

- Yeah.

Well, Dr. Angelica Kloos, Julie Petrin, Erin Demsher, Kelly Feiler, thank you all so much for being part of this program and for your ongoing work in the area of youth mental health in Pennsylvania.

And for more information, visit wvia.org/mindovermatter.

And remember, you are not alone.

On behalf of WVIA, I'm Tracy Matisak.

Thanks for watching.

Colby's Story - Youth Mental Health

Clip: 2/29/2024 | 1m 1s | Colby Hughes shares her story about her Obsessive Compulsive Disorder diagnosis (1m 1s)

Clip: 2/29/2024 | 5m 42s | Hear the story of how Delaney was affected by isolation and anxiety due to the pandemic (5m 42s)

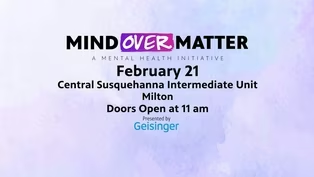

Youth Mental Health - Join Our Audience

Preview: 2/29/2024 | 29s | Join our Live Studio Audience February 21 (29s)

Youth Mental Health Matters - Preview

Preview: 2/29/2024 | 30s | Watch Thursday, February 29th at 7pm on WVIA TV (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Explore scientific discoveries on television's most acclaimed science documentary series.

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Mind Over Matter is a local public television program presented by WVIA