|

|

|

by Peter Tyson March 16, 1999 No rock speaks such volumes as the Unfinished Obelisk. Commanding the presence of a lost city from its rocky bed in an ancient quarry high above Aswan, it speaks of the hubris of the pharaohs and the grueling labor of their minions, of the triumphs of quarrying and its unimaginable failures. Had it ever made it out of its stone cradle and assumed its position before Karnak (or wherever its creator planned to place it), it would have been the greatest obelisk ever raised, a monument worthy perhaps of "Wonder of the Ancient World" status. As it is, the Unfinished Obelisk is the obelisk raisers' most grievous tragedy, a lasting reminder of the limits of human engineering. If it had been extracted and erected as originally conceived, the Unfinished Obelisk would have stood 137 feet tall and weighed 1,168 tons, dwarfing all others. (The largest survivor, the Lateran obelisk in Rome, rises 105 feet and weighs 455 tons.) However, months or perhaps years into its removal, fissures began to appear in the granite. With each crack, its designers scaled back the size of the obelisk, but each time the quarrymen came upon a new one. When they uncovered a profound fissure near the obelisk's center, the project was abandoned. "[T]he Aswan Obelisk," wrote the English archaeologist Reginald Engelbach, "enables the visitor to look with different eyes on the finished monuments, and to realize ... the heartbreaking failures which must sometimes have driven the old engineers to the verge of despair before a perfect monument could be presented by the king to his god."

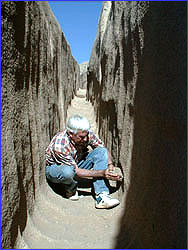

Its history is obscure. As Engelbach notes, since it was a failure, it was in no one's interest to lay claim to the obelisk, and we have no idea who commissioned it. As I stood beside its enormous bulk yesterday—each side at the base is almost 14 feet high—I kept whispering to myself, "The audacity ... The audacity ...." You just can't believe that anyone would try to carve, much less move, much less erect such a hillside of rock. Until, perhaps, you recall the achievements of pharaohs like Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III, who together were responsible for 10 of the 17 obelisks erected at Karnak and who scholars believe are the most likely candidates. (Personally, I'd bet on the granddaddy of all monument-builders, Ramses the Great.) As I stepped through the deep, rock-hewn trenches that define the obelisk, my shoulders brushing the rock on either side, my mind was not on the pharaohs, however, but on their quarrymen. For months and months, in that cramped space under the unrelenting sun, and all for naught, they had bashed out those scalloped trenches with cantaloupe-sized pounders of dolerite. Engelbach estimated that at any one time 130 men each worked a pair of scallops, in a space about four feet square.

Imagine, then, doing this for hours and hours, day in and day out, for months on end—for your life. (Your life must have been brutally short.) Though evidence for slavery in this context is inconclusive, the labor was certainly compulsory. (As Lehner put it: "They didn't have Locke or Hobbes, no concept of individuality or freedom, no unions. It's hard to think it was fun.") If there was a silver lining to the abandonment of the Unfinished Obelisk, I thought, it was that the workers were spared having to pound it out underneath, which must have been the most back-breaking work of all. But then again, perhaps they felt cheated after all that effort. As we left the quarry in the late afternoon yesterday, the low-angled sun burning the cliffs amber, the phrase "galling beyond words" kept floating around in my head. It comes from a line of Engelbach's: "It must have been galling beyond words to the Egyptians to abandon it after all the time and trouble they had expended, but today we are grateful for their failure, as it teaches us more about their methods than any other monument in Egypt."

Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Obelisk Raised! (September 12) In the Groove (September 1) The Third Attempt (August 27) Angle of Repose (March 25) A Tale of Two Obelisks (March 24) Rising Toward the Sun (March 23) Into Position (March 22) On an Anthill in Aswan (March 21) Ready to Go (March 20) Gifts of the River (March 19) By Camel to a Lost Obelisk (March 18) The Unfinished Obelisk (March 16) Pulling Together (March 14) Balloon Flight Over Ancient Thebes (March 12) The Queen Who Would Be King (March 10) Rock of Ages (March 8) The Solar Barque (March 6) Coughing Up an Obelisk (March 4) Explore Ancient Egypt | Raising the Obelisk | Meet the Team Dispatches | Pyramids | E-Mail | Resources Classroom Resources | Site Map | Mysteries of the Nile Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

The Unfinished Obelisk at Aswan dwarfs archaeologist

Mark Lehner.

The Unfinished Obelisk at Aswan dwarfs archaeologist

Mark Lehner.

Crouching in the trench made by ancient quarrymen,

Denys Stock, an expert on ancient Egyptian tools,

demonstrates how the quarrymen might have wielded a

dolerite pounder to carve out the obelisk.

Crouching in the trench made by ancient quarrymen,

Denys Stock, an expert on ancient Egyptian tools,

demonstrates how the quarrymen might have wielded a

dolerite pounder to carve out the obelisk.

Each worker is thought to have worked a pair of

scallops, pounding away the granite inch by brutal

inch.

Each worker is thought to have worked a pair of

scallops, pounding away the granite inch by brutal

inch.

Stonemasons proudly pose with their near-finished,

25-plus ton obelisk.

Stonemasons proudly pose with their near-finished,

25-plus ton obelisk.