|

|

|

by Peter Tyson March 14, 1999 It might have been the 20th century B.C. in our small corner of Hamada Rashwan's Aswan quarry today. Eight or ten quarrymen squatted atop a long sliver of granite, chiseling it into an obelisk. Others kindled small fires atop other slabs of granite before trying to break off slices loosened by the heat. Wood smoke hung in the air, as did the tap-tap-tap of dolerite balls striking yet other blocks of granite, whose dimpled surface workers sought to bring into a semblance of smoothness. Most noticeably, a crowd of 50 Egyptian laborers, encouraging one another with raucous cries of mutual support, yanked on ropes attached to a truck-sized block of stone. Weighing perhaps 25 tons, the block rested on a wooden sledge, which the workers were trying to haul along a patch of ground. Earlier, they had firmed up the ground with embedded wooden sleepers laid down crosswise like railroad ties, and had lubricated the sleepers with greasy smears of tallow. The rock had not yet budged, but we were hopeful. Why the 20th-century B.C.? Well, we know the ancient Egyptians chipped granite, used dolerite pounders, and built embrittling fires to help shape granite. And we know they designed wooden sledges to transport heavy statues.

And why were we doing all this? Because our obelisk-raising team had finally assembled itself in its entirety here in Aswan and had begun to undertake various tests of how the ancients quarried, worked, moved, shipped, and raised obelisks. The biggest test of the day, of course, was the sledge-hauling. We don't know if we had the particulars of the ancient technology exactly right—we used tallow, they might have used water or oil; our ropes were of sisal, theirs perhaps of halfa grass; and so on—but we came as close as we could. The question now was, would it work?

Actually, it moved only a few inches, and then a rope—perhaps weakened by rubbing against the rock—parted, flinging chief foreman Abdel Aleem and a bunch of others onto their backs. A lunch break was called. It was now about 3 p.m., and we had managed to move the sledge only about two feet. Mark Lehner told me that, to symbolize the word for "marvel" or "wonder," the Egyptians used the hieroglyph for sledge, indicating how well this device worked for them. Would it do so for us? At lunch, each of our experts had a different theory as to why it had barely budged. "We weren't strong enough," Owain Roberts said with a chuckle, adding that a few more pullers should do it. Hopkins, not surprisingly, felt we needed more levers and better levering points. For Mark Whitby, the problem lay in communication. No one seemed to be fully in charge, he said, which proved especially troublesome with so many nationalities involved. I couldn't find Aleem, but earlier he had said that 50 men alone could move it—if it rested on rollers. Finally, Mark Lehner said he thought the pullers had simply not yet achieved the required rhythm, which he said could conceivably take hours.

But with the sun starting its descent to the dust-colored horizon, another rope separated, then another. Each time, Roberts retied them with the help of some of the quarrymen. Yet the day was quickly dying. Finally, Hopkins called out: "This is the last time!" Then, from on high, he turned to 200-plus leverers and pullers, and yelled at the top of his lungs, "ALLAH AKBAR!! (GOD IS GREAT!)" The sledge jumped and, for the first time, kept on going. One foot, two feet, five feet. Only after about ten feet did it finally grind to a halt.

It may not sound like a great distance—and I did overhear one or two experts express private disappointment and surprise that we had not achieved greater—but you couldn't convince the workers of that. As soon as the rock stopped, a cheer went up that I'd bet you could hear right across to the Aga Khan Mausoleum on the other side of the Nile, and several of the men lofted a beaming Hopkins high into the air. Next: The Unfinished Obelisk Peter Tyson is Online Producer of NOVA. Obelisk Raised! (September 12) In the Groove (September 1) The Third Attempt (August 27) Angle of Repose (March 25) A Tale of Two Obelisks (March 24) Rising Toward the Sun (March 23) Into Position (March 22) On an Anthill in Aswan (March 21) Ready to Go (March 20) Gifts of the River (March 19) By Camel to a Lost Obelisk (March 18) The Unfinished Obelisk (March 16) Pulling Together (March 14) Balloon Flight Over Ancient Thebes (March 12) The Queen Who Would Be King (March 10) Rock of Ages (March 8) The Solar Barque (March 6) Coughing Up an Obelisk (March 4) Explore Ancient Egypt | Raising the Obelisk | Meet the Team Dispatches | Pyramids | E-Mail | Resources Classroom Resources | Site Map | Mysteries of the Nile Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

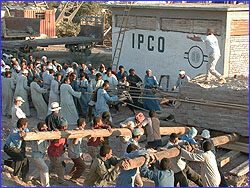

At Rashwan's quarry, Egyptian laborers await the call

to have another go at the ropes.

At Rashwan's quarry, Egyptian laborers await the call

to have another go at the ropes.

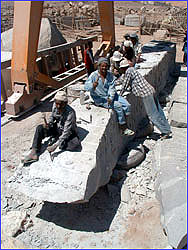

Stonemasons have been working round the clock to

shape the NOVA obelisk.

Stonemasons have been working round the clock to

shape the NOVA obelisk.

Just as the block begins to move, a rope breaks.

Just as the block begins to move, a rope breaks. Roger Hopkins directs the tugging operation from atop

the 25-ton block.

Roger Hopkins directs the tugging operation from atop

the 25-ton block. Jubilant workers celebrate a good day's work by

giving Roger Hopkins a victory lift.

Jubilant workers celebrate a good day's work by

giving Roger Hopkins a victory lift.